The Collection

J. Pierpont Morgan’s new Library was a treasury, not a place to curl up with a good book. In 1908, after a London Times journalist was offered a rare look inside, the New York Times printed this breathless front-page headline:

MR. MORGAN’S GREAT LIBRARY . . . One of the Chief Treasure Houses of the World. PARADISE OF THE BOOKMAN Bewildering Array of Noble Products of the Minds and Hands of Many Centuries. MORGAN CALLED A GENIUS “The Most Wonderful of All Collections by the Most Wonderful Collector, Perhaps, of Any Time.”

Hype and hyperbole aside, it was true that Morgan had gathered a “bewildering array” of bibliographic treasures and works of art. On view here are just a few of the medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts, rare printed books and bindings, literary and historical manuscripts, drawings, and prints the Times reporter saw during that early visit. Morgan had acquired them all (and much more) largely in the space of a decade. Morgan’s Library, the correspondent declared, was a place where “all the dreams of the bibliophile come true.”

Page from a Rajput manuscript of the Ragamala, created in India, probably Jaipur, ca. 1800. The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.211.

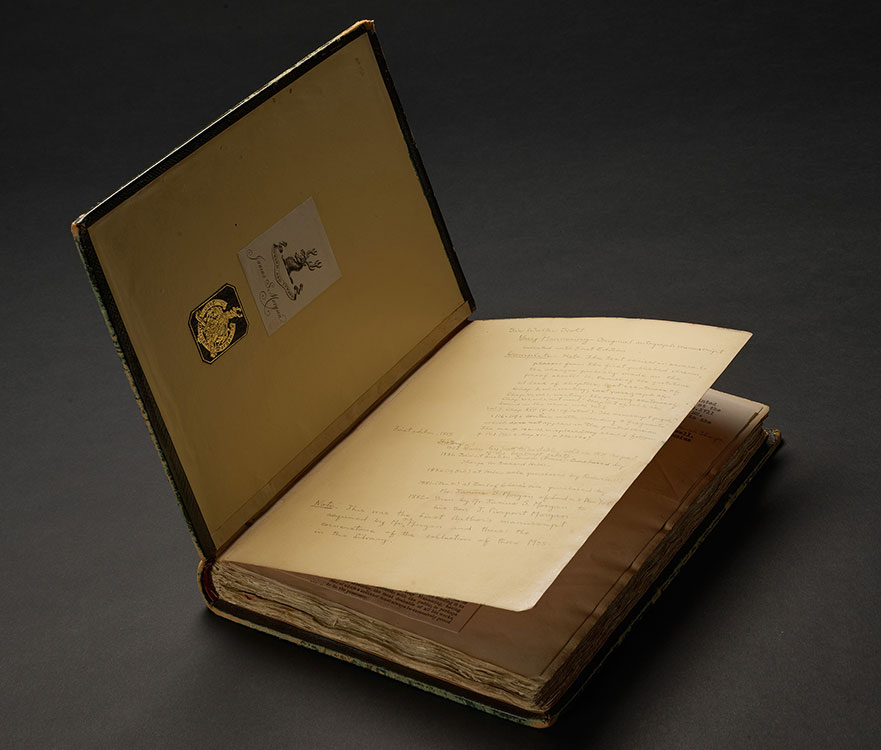

The "Cornerstone" of the Literary Manuscripts Collection

In 1881 Morgan’s father, Junius, learned that the manuscript of Sir Walter Scott’s second novel would be sold at auction. “If it’s genuine beyond the possibility of a doubt,” Junius told his agent, “I should like to own it.” Junius placed a successful bid of £390 and added his bookplate to this volume. Within a year, he presented the manuscript as a gift to his son, who placed his leather bookplate just below. Both feature the family motto, Onward and Upward. The extensive notes on the right were added years later by Belle da Costa Greene, the Morgan Library’s first director. At the foot of the page, she cited the item’s institutional significance.

Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832)

Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer

Autograph manuscript (one of three volumes), 1814–15

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by Junius S. Morgan, 1881, subsequently gifted to his son, J. Pierpont Morgan; MA 436–38

A 1663 Bible in the Wampanoag (Massachusett) Language

One of Morgan’s earliest notable purchases was both a landmark of American book history and an artifact of settler colonialism. The first complete Bible printed in the Western Hemisphere, the book was a project of the Reverend John Eliot (1604–1690), an English missionary of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This translation aligned with Eliot’s efforts to convert Native peoples to Christianity and divorce them from their traditional ways of life.

Morgan purchased this copy for $1,000 at the 1879 auction of Connecticut banker George Brinley’s library. The New York Times called it “the crowning wonder of the sale.”

Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God (The Holy Bible: Containing the Old Testament and the New)

Cambridge, MA: printed by Samuel Green and Marmaduke Johnson, 1663

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1879; PML 5441

Blake's Drawings for the Book of Job

The highlight of the 1902–3 rare-book auction season in England was a series of watercolors and proof engravings by the visionary English artist and poet William Blake. With Bernard Alfred Quaritch (son of the renowned London bookseller Bernard Quaritch) acting as his agent at Sotheby’s, Morgan purchased the collection for what the New York Times called the “sensational” sum of £5,712. One contemporary commentator noted the irony of the “phenomenally high prices” realized at the sale, given “Blake’s indifference to what the majority of us regard as the tangibilities of life.”

View the Morgan’s collection of Blake drawings

William Blake (1757–1827)

Job’s Sons and Daughter Overwhelmed by Satan, ca. 1805–10

Pen and black and gray ink, gray wash, and watercolor, over traces of graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1903; 2001.65</job’s>

Rembrandt in the Library

This etching depicts an art collector in a moment of ease, a print or drawing in his hands and an open album on the table before him. Abraham Francen, the apothecary and connoisseur depicted, was apparently not a person of enormous means, but Rembrandt portrayed him in the company of rich and beautiful things—much like Morgan in his bookman’s paradise.

This is one of 112 prints by Rembrandt that Morgan purchased in 1905 from the collector George W. Vanderbilt, augmenting the 272 he had acquired with the library of Theodore Irwin in 1900. Morgan stored his print collection in custom cabinets in the top-floor “work room,” accessible to staff via elevator or a marble spiral staircase.

View the Morgan’s collection of Rembrandt etchings

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606–1669)

Abraham Francen, Apothecary, ca. 1657

Etching, engraving, and drypoint on Japanese paper

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1905; RvR 373

Women in the Bookman's Paradise

In 1896 Morgan acquired the manuscripts of two French novels by George Sand (one of which is shown here) and soon added manuscripts by the nineteenth-century English authors Anne and Charlotte Brontë. In 1893 Morgan passed on Lady Susan, the only surviving manuscript of a novel by Jane Austen. The Morgan Library eventually acquired it in 1947, long after Pierpont’s death.

While today most collectors prefer literary manuscripts to retain their original format, in Morgan’s day booksellers often had them sumptuously bound. This heavily gold-tooled leather binding by the London firm Riviere & Son is a typical example.

George Sand (1804–1876)

Les dames vertes

Autograph manuscript, ca. 1858, later bound in gold-tooled green morocco by Riviere & Son

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1896; MA 401

The Golden Gospels of Henry VIII

This thousand-year-old manuscript was created by about sixteen scribes in a Benedictine abbey in Trier (in what is now Germany). They used gold ink to copy the text of the Gospels onto parchment that had been dyed with a plant-based purple pigment, creating a luxury object that was likely an imperial gift. Though it was made in the tenth century, the manuscript has come to be known as the Golden Gospels of Henry VIII because the English monarch owned it some five centuries later. Morgan acquired it in 1900 as part of an en bloc purchase of more than three thousand books and manuscripts from the American manufacturer and financier Theodore Irwin.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Trier, ca. 980

Written and decorated in the Benedictine Abbey of St. Maximin

Purple parchment surface-dyed with orchil, gold letters

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.23

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan with the Irwin Collection, 1900

The Gutenberg Bible

There was a particular book that Morgan simply had to have as he began to direct significant resources to his library. He acquired this copy of the Gutenberg Bible in 1896 from the London firm Henry Sotheran & Co., paying £2,750. A landmark of printing history, it was the first substantive European book created with moveable type.

But one Gutenberg—even this desirable copy printed on vellum—would not prove sufficient. Morgan acquired two more, both printed on paper: a copy of the Old Testament (purchased with the Theodore Irwin collection in 1900) and a complete copy in two volumes (purchased in 1911 from the London dealer Bernard Quaritch).

View the Morgan’s Old Testament copy of the Gutenberg Bible

Biblia latina (Latin Bible)

Mainz: Johann Gutenberg and Johann Fust, ca. 1454–55

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1896; PML 818

The Lindau Gospels

In 1899 Morgan received a telegram from his nephew Junius in London, alerting him to the availability of a “treasure of great value.” Writing in code, as was the Morgans’ custom when sending international wires, Junius offered tantalizing details about what would become the foundation of his uncle’s medieval manuscript collection: this ninth-century Gospel Book enclosed between jeweled metalwork covers. It came to be known as the Lindau Gospels because it was once housed in the Abbey of Lindau in Germany.

Morgan met the asking price of £10,000. The British government attempted, but failed, to raise the funds to keep this prize in the United Kingdom. By 1901 the volume was released to Morgan. When his new Library was completed five years later, he would have the volume installed alongside other dazzling bindings in a tabletop vitrine in the East Room.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Switzerland, St. Gall, ca. 880 (manuscript)

Eastern France, ca. 870 (front cover)

Austria, Salzburg region, ca. 780–800 (back cover)

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.1

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1901

Follower of Raphael

This painting was found by the artist and agent Charles Fairfax Murray and sold via a Roman gallery to J. Pierpont Morgan in 1910. After Morgan’s Library was completed, he sought this and other Italian Renaissance paintings to adorn the red-damask-covered walls of the West Room, his study.

The work was believed to be Raphael’s Holy Family (also known as the Madonna di Loreto), which had long been considered lost. Today, however, most scholars accept that the Musée Condé in Chantilly, France, has Raphael’s original and that this is one of numerous copies. The quality and refinement of the Morgan’s version suggest that it was executed by one of Raphael’s assistants during the master’s lifetime or shortly after his death in 1520. The Christ Child gazes at the Virgin and reaches toward her skillfully rendered veil—a reference to Christ’s shroud, or burial garment.

Follower of Raphael (Italian, early sixteenth century)

Holy Family, ca. 1515–20

Oil on canvas

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1910; AZ139