Reactions

Unknown photographer

James Joyce and Sylvia Beach at Shakespeare and Company, ca. 1926

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

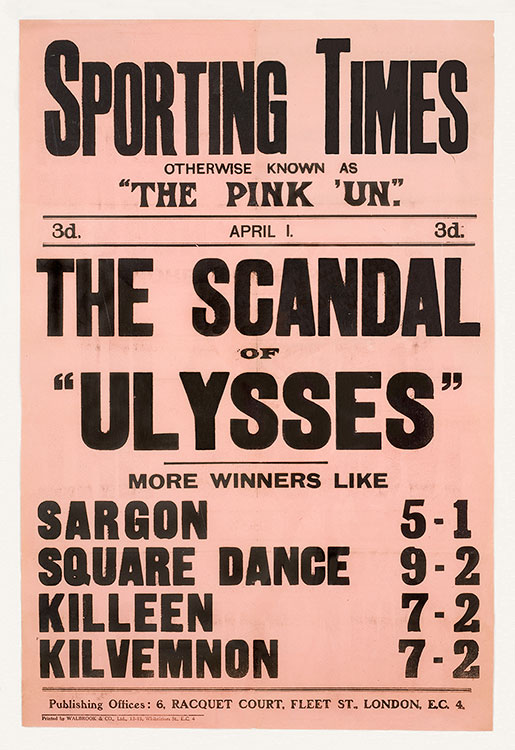

The Scandal of Ulysses

Sylvia Beach and Harriet Shaw Weaver both collected clippings on Joyce’s behalf. After noticing the “Scandal” screamer in the Sporting Times, a London weekly, Weaver obtained copies of placards advertising the issue and sent at least two to Paris for Joyce and Beach. The Sporting Times write-up emphasized the book’s scabrous qualities, calling it a “stupid glorification of mere filth” and “literature of the latrine”; but the word “scandal” referred equally to the reviewer’s verdict of tediousness. Joyce chose one of the writer's sentences calling Ulysses “intensely dull” for Weaver's leaflet of press notices promoting the novel. Beach displayed another copy of this placard in her shop for years.

Placard for the Sporting Times, 1 April 1922

[London: Walbrook & Co., 1922]

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

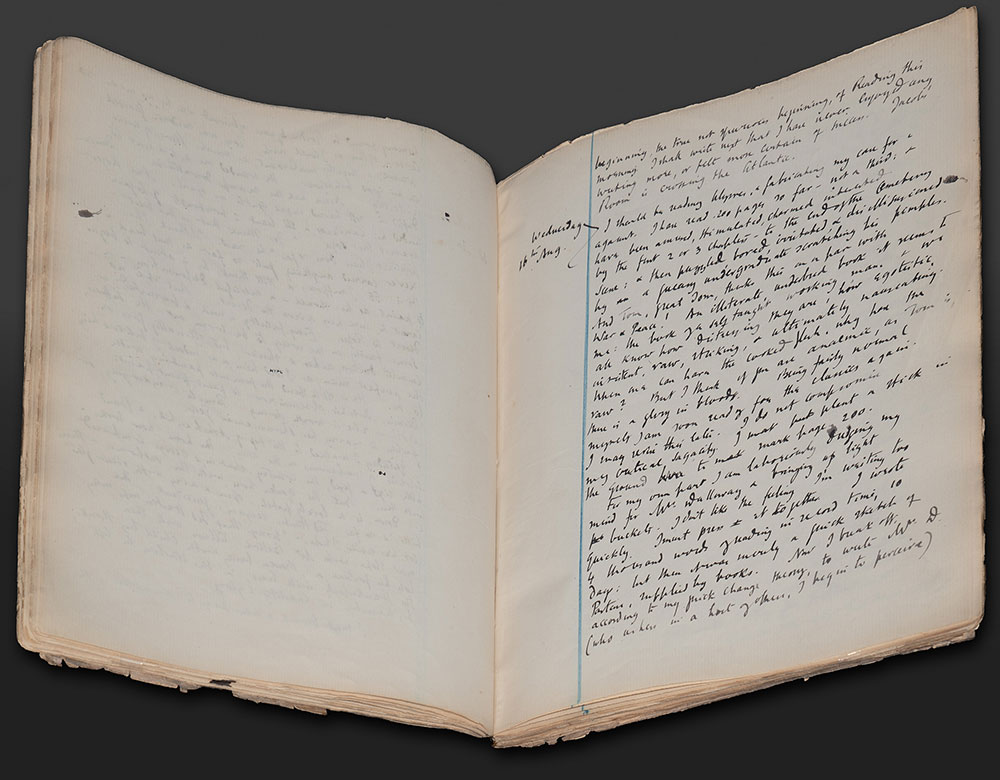

Virginia Woolf Responds

Virginia Woolf’s diary entry, which begins,“I should be reading ‘Ulysses’ and fabricating my case for and against,” conveys a mix of emotions and opinions about the novel’s first two hundred pages. Stimulated and amused by early episodes, Woolf is ultimately repulsed by its graphic passages. Shocked that “great Tom” (T. S. Eliot) rates it on a par with Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Woolf calls Ulysses an “underbred” novel by an egoistic “self-taught working man.” Elsewhere in her diary and writings, Woolf sets aside some of her condescension and recognizes that Joyce was rehearsing aspects of narrative that she herself had begun to articulate and would realize in her own way: “to record the atoms as they fall upon the mind in the order in which they fall,” “an ordinary mind on an ordinary day.”

Installation shot of Virginia Woolf (1882–1941), Diary entry, 16 August 1922

The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

© The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf

Ulysses, when it appeared, created a great stir. Figures like T.S. Eliot and W.B. Yeats praised the book highly, but there were others who viewed it much more suspiciously, including Virginia Woolf. Her diary entry on the book begins,“I should be reading Ulysses and fabricating my case for and against.” And she was stimulated and amused by an early episode, but eventually, she was shocked by its graphic passages. She called Ulysses “Underbred novel, by an egotistical, self taught working man,” which James Joyce certainly wasn't. But elsewhere, she did set aside some of her condescension and she did recognize that Joyce was rehearsing aspects of narrative, that indeed she herself was working with, “To record,” as she said, “the atoms as they fall upon the mind, the order in which they fall, an ordinary mind on an ordinary day.”

George Antheil

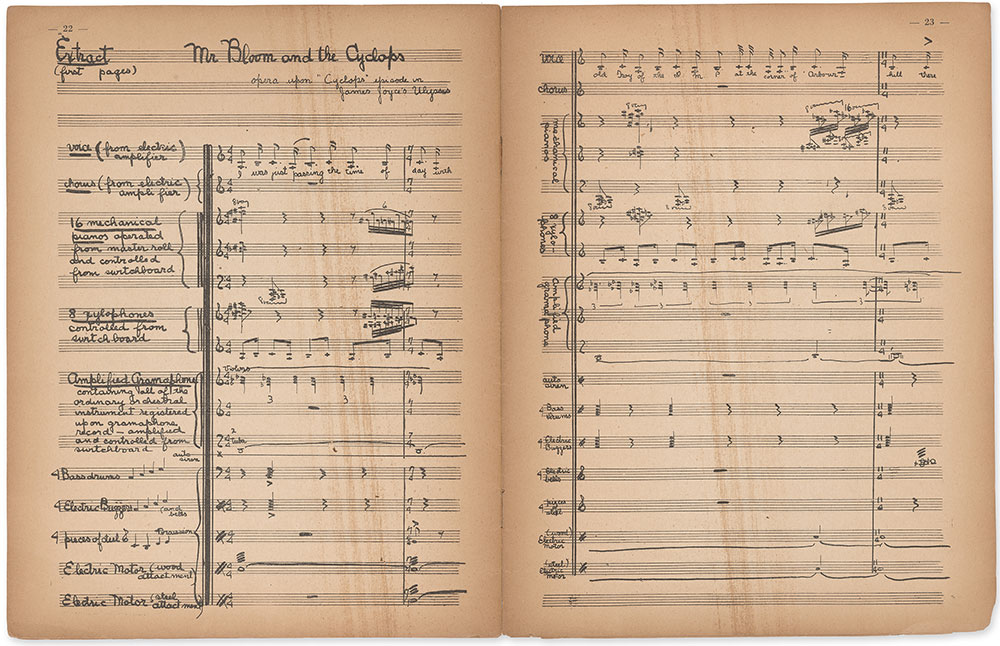

In early 1924 the Chicago Tribune heralded a new “electric opera” based on Ulysses by the modern composer George Antheil (1900–1959). The classically-trained New Jersey native was then living in Paris above Shakespeare and Company. Joyce and Nora became fond of the young avant-garde musician. They attended several of Antheil's riotous Paris concerts and remained friends for years. Despite his conservative taste in music, Joyce encouraged Antheil to complete the experimental work based on the "Cyclops" episode, giving him one of the coveted copies of the Ulysses Schema to aid in his endeavor.

Despite the advance publicity, Antheil never finished "Mr Bloom and the Cyclops." Instead, he became famous for the piece he was composing simultaneously: Ballet mécanique, with its player pianos, amplifiers, sirens, and standing fans simulating airplane propellers. As indicated on the fragment of the “Cyclops” score published in 1925, his Ulysses opera was arranged for electric motors, buzzers, amplified voices, gramophones, and sixteen player pianos. Subsequent collaborations between Joyce and Antheil also came to naught, though Antheil later published a musical setting of Joyce's poem "Nightpiece."

George Antheil (1900–1959)

“Mr Bloom and the Cyclops”

This Quarter 1, no. 2, Musical Supplement (October 1925)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Annette de la Renta in memory of Carter Burden, 2005; PML 129675

Unknown Photographer

Sylvia Beach and George Antheil Climbing Up to His Apartment, ca. 1923

Private collection

© Estate of Peter Antheil

Jorge Luis Borges

Borges refers to himself in a 1925 review of Ulysses on display as the first Hispanic adventurer to have reached the novel’s untamed country. The piece appears in an issue of Proa along with Borges's loose translation of the last passage of "Penelope." A letter from Borges to Guillermo de Torre and their shared copy of Ulysses, both in the Morgan's collection, document ways in which Joyce's work resonated for avant-garde writers in Argentina attempting to distinguish their work and their language from Spanish literature. Throughout his life, Borges would praise Joyce’s relation to time, merging of dream and waking, and creation of a total reality. But Borges also characterized Ulysses almost as a monstrosity, a text so expansive and elaborate that it was impossible to read or understand in its entirety. Borges’s own masterly short fiction often centers on themes suggestive of Joyce’s encyclopedic approach to creating Ulysses. Scholars have also noted that several of Borges’s characters are portrayed as Ulysses’ ideal readers—figures with infinite memories, such as Ireneo Funes, whom Borges mentioned in his 1941 obituary for Joyce.

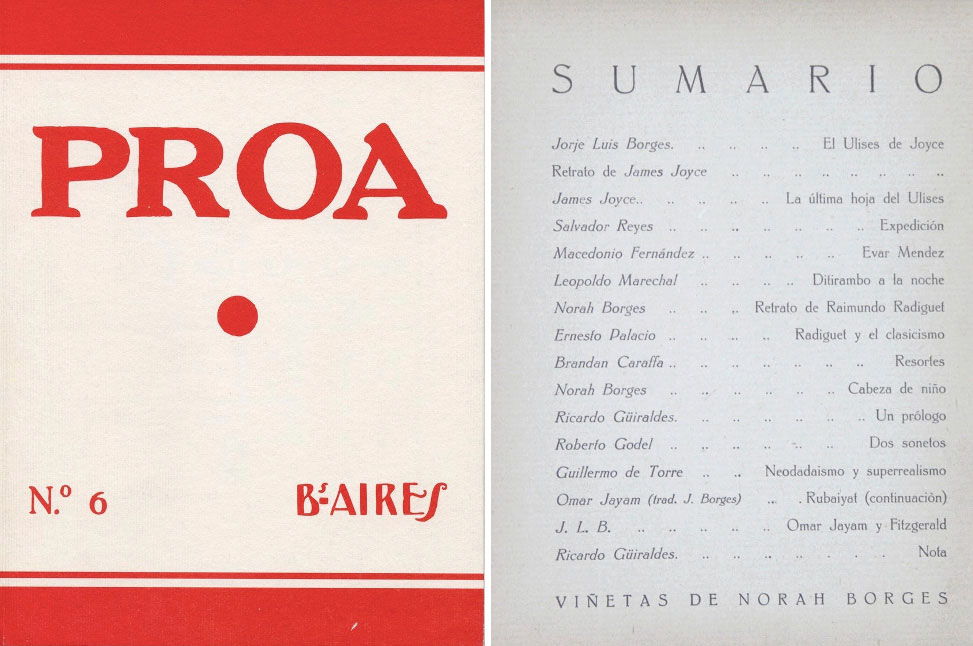

Cover and table of contents for Proa, no. 6 (January 1925)

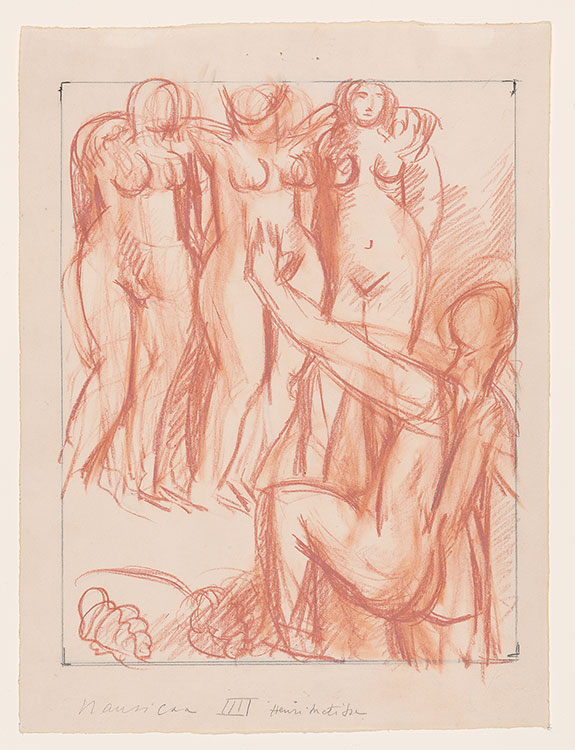

Henri Matisse

The French painter Henri Matisse depicted figures related to the novel’s Homeric allusions for a deluxe edition of Ulysses in 1935. He was not adept at reading English and gave up on tackling the monumental novel in translation. As an alternative, a friend loaned him a book-length study of the novel by Stuart Gilbert. Writing under Joyce’s supervision, Gilbert had emphasized the work’s correspondences to classical literature. The artist was also given a copy of the Random House circular How to Enjoy James Joyce’s “Ulysses”, which made use of Joyce's Schema. When the edition’s publisher, George Macy, was unable to see connections between Matisse’s first two prints and the novel, the painter curtly relayed through his son that Random House had explicitly stated,“Nausicaa = Gerty MacDowel” [sic]. Joyce consented to Matisse’s approach over the telephone, the sole direct contact that transpired between artist and author.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses. Illustrated by Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

New York: Limited Editions Club, 1935

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197805

Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

Preparatory drawing for Ulysses [the “Nausicaa” episode], 1934 Red chalk

The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation

© 2022 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York [permission not yet granted]

Vladimir Nabokov

Nabokov drew this diagram, which maps the itineraries of Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus in twelve episodes, for a course he taught called Masters of European Fiction. The Russian American novelist described these classes as “a kind of detective investigation of the mystery of literary structures.” He encouraged his pupils to approach artworks as entirely new worlds, study them closely in and of themselves, and “fondle the details.” In his notes for Ulysses, Nabokov draws attention to the novel’s synchronicities as exemplary of Joyce’s supreme artistic control—pointing out the near misses and intersections of Bloom and Stephen (“a kind of slow dance of fate”) and of language, gesture, and thought—“Everything is in correspondence.”

Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977)

Map of Leopold Bloom’s and Stephen Dedalus’s travels through Dublin, ca. 1948–58

Graphite and colored pencil

The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

© Vladimir Nabokov, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC

Ralph Ellison

A letter on view from Ralph Ellison to the critic Kenneth Burke was written in 1945 soon after Ellison published “Richard Wright’s Blues,” an essay that includes a comparison of Wright’s rejection of his cultural origins as a Black man in the US South to Joyce’s rejection of Ireland. Ellison expanded his ideas in a public lecture that year at Bennington College and, when later speaking to a class, had an epiphany, as he tells Burke: “I went to Joyce for illumination of Negro life only to discover that it works both ways and that Negro life illuminates much of Joyce. From that single experience at Bennington I believe I have the key to a whole new system of Negro education. I know too much, however, about how this country is run to believe anyone would take an interest in doing anything about it.”

Ralph Ellison

Photographed in 1960 by a United States Information Agency staff photographer. NARA reference number 306-PSA-61-8989

Robert Motherwell

When the American painter Robert Motherwell created a foundation in 1981, he named it after Joyce's character Stephen Dedalus. Motherwell was twenty in 1935 when he discovered a copy of Ulysses in a Paris bookstall. The artist was searching for a key to his own modernist aesthetic, he later said, and found one in Joyce. Throughout his life, he would return to the author’s books whenever he became discouraged: “A writer like Joyce can make me just want to paint. The magic of painting is there. It gives me almost a chill what words can do.” Motherwell’s first artworks referencing the author date from the late 1940s, though it was not until publisher Andrew Hoyem commissioned this edition in the 1980s that the artist took on the entire novel. Freely responding to Joyce’s writing, Motherwell produced line etchings evocative of calligraphic scrawls.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses. Illustrated by Robert Motherwell (1915–1991) San Francisco: Arion, 1988

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197878

© 2022 Dedalus Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Spencer Finch

Finch’s book, which relates to his art installation Ulysses (September 19, 2014), records the artist’s wanderings through New York on one day. Charted as a progression of the colors he encountered, the book evokes personalized travel maps from the twentieth century, called TripTiks, and Pantone’s commercial color-matching swatches. Finch documents the source of each hue in brief captions, such as “fire hydrant,” “moss on gravestone,” and “subway.” At one point, the chromatic litany of New York shifts from the everyday to the transcendent when Finch looks at a book and artworks by Josef Albers (1888–1976).

Spencer Finch (b. 1962)

Ulysses

Brooklyn: Trying to Press, [2016]

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund for the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection, 2021; PML 198671

© Spencer Finch, 2022