Ulysses in New York

The sensationalism surrounding Ulysses in the media and the absence of international copyright law in the 1920s encouraged “bookleggers” such as Samuel Roth (1893–1974), who serialized the novel in his magazine Two Worlds Monthly without Joyce’s consent. At that time, foreign authors had to publish their work in America in order to secure a US copyright; this was impossible for Joyce, however, since Ulysses was banned. Roth skirted the ban by censoring the text himself, mangling it in the process. With little recourse, Sylvia Beach and Joyce started a petition that called on American readers and media outlets to boycott all of Roth’s ventures. Virginia Woolf, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, and André Gide were among the scores of eminent signatories. The statement appeared in newspapers and was issued as a broadside.

In 1928, Joyce and Beach obtained an injunction barring the American from advertising Joyce's name, nothing more. Unrepentant, Roth pirated Joyce's entire novel the following year, issuing the first American edition of Ulysses under the false imprint of “Shakespeare and Company, Paris.” The production was shoddy: a line of type was printed upside-down and the text was corrupt. Hundreds, if not thousands, of copies were distributed through the book trade (Random House inadvertently consulted a copy in 1933 when proofing their text of the first authorized American edition). Roth, who endured several stints in jail for dealing in so-called pornographic books, would later become a significant figure in landmark cases relating to obscenity.

"International Protest" [Statement regarding the piracy of James Joyce’s Ulysses by Samuel Roth]

[Paris: s.n., 1927]

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund for the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection, 2017; PML 197710

Detail of page from James Joyce (1882–1941), Ulysses (Paris [i.e., New York]: Shakespeare and Company [i.e., Samuel Roth and Max Roth], 1927 [i.e., 1929])

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197795

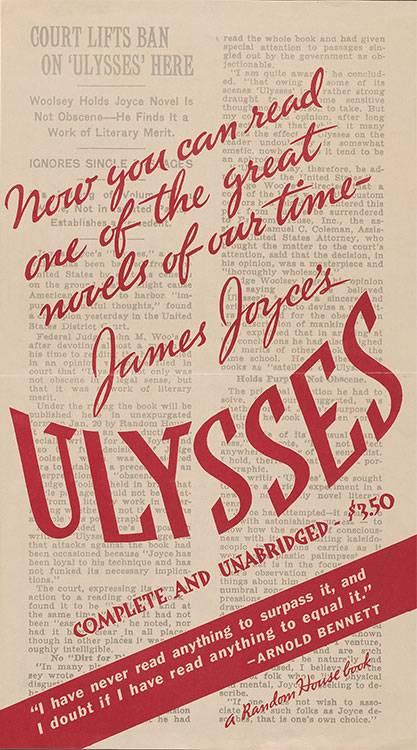

Judge Woolsey's Book Review

When Joyce signed a contract with publisher Bennett Cerf’s Random House in 1932, Ulysses was still illegal in the United Sates. In partnership with ACLU lawyer Morris Ernst, Cerf set out to challenge the ban by importing a copy of Ulysses in plain sight, coaxing the government to put the book on trial. The package entered New York harbor unnoticed and made its way to Cerf’s office, prompting Ernst to return it to US Customs agents and, putting on an act, demand that the “suspicious” package be opened and subsequently seized. Within a few days, Cerf sent a circular letter to “editors, critics, authors, clergymen, members of the bar, sociologists, psychologists, teachers and libraries” to solicit opinions about the novel. Letters received in response became part of a strategic body of documentation, attesting to the book’s artistic value. In court Ernst argued for the novel’s literary merits. Judge John Munro Woolsey’s 1933 decision agreed that Ulysses was “a sincere and serious attempt to devise a new literary method for the observation and description of mankind”—its allegedly obscene passages more likely to nauseate than sexually arouse. Woolsey’s friends printed his opinion in this pamphlet as the “latest . . . book review by Judge Woolsey.”

United States District Court (New York: Southern District)

United States of America, Libelant vs. One Book Called “Ulysses”

Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1935

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197837

The Random House Edition

Moments after Judge Woolsey’s 6 December 1933 ruling, word was handed down to Random House’s typesetters to begin printing. Ulysses was published in America on 25 January 1934 in an edition of around ten thousand. The novel’s backstory and Bennett Cerf’s marketing strategies had all but guaranteed a smash hit. By 1939 over fifty thousand copies had been sold. Woolsey’s legal decision was printed at the front of the book, and Joyce contributed a letter about its publication history in place of an introduction.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses

Book design by Ernst Reichl (1900–1980)

New York: Random House, 1934

The Morgan Library & Museum, bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987; PML 135629

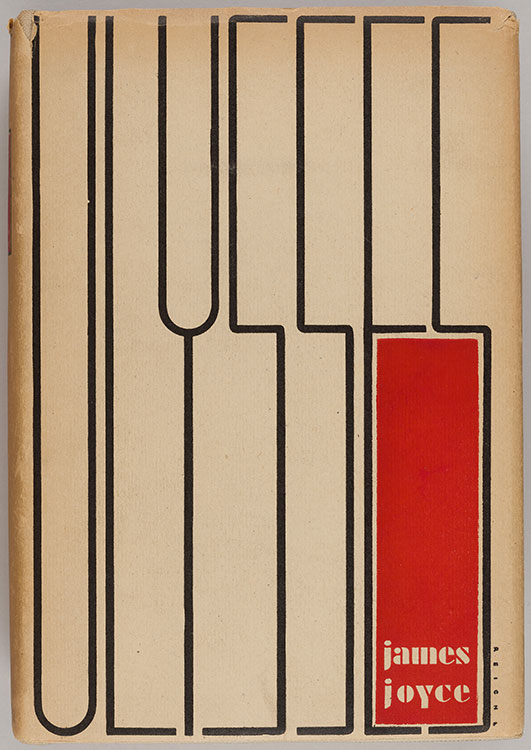

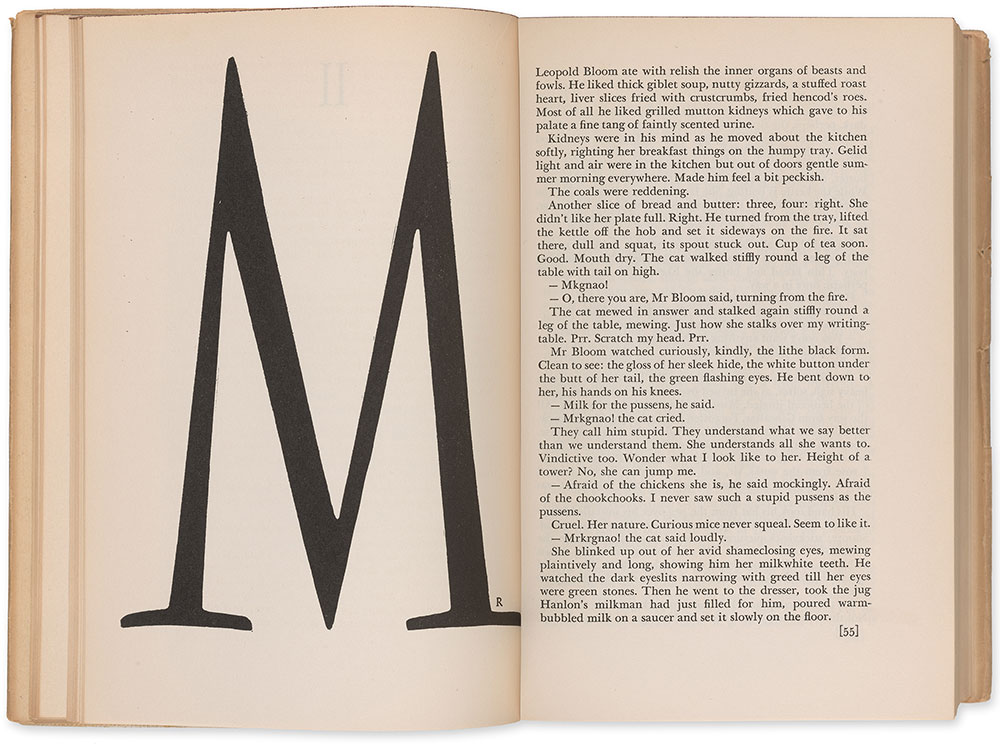

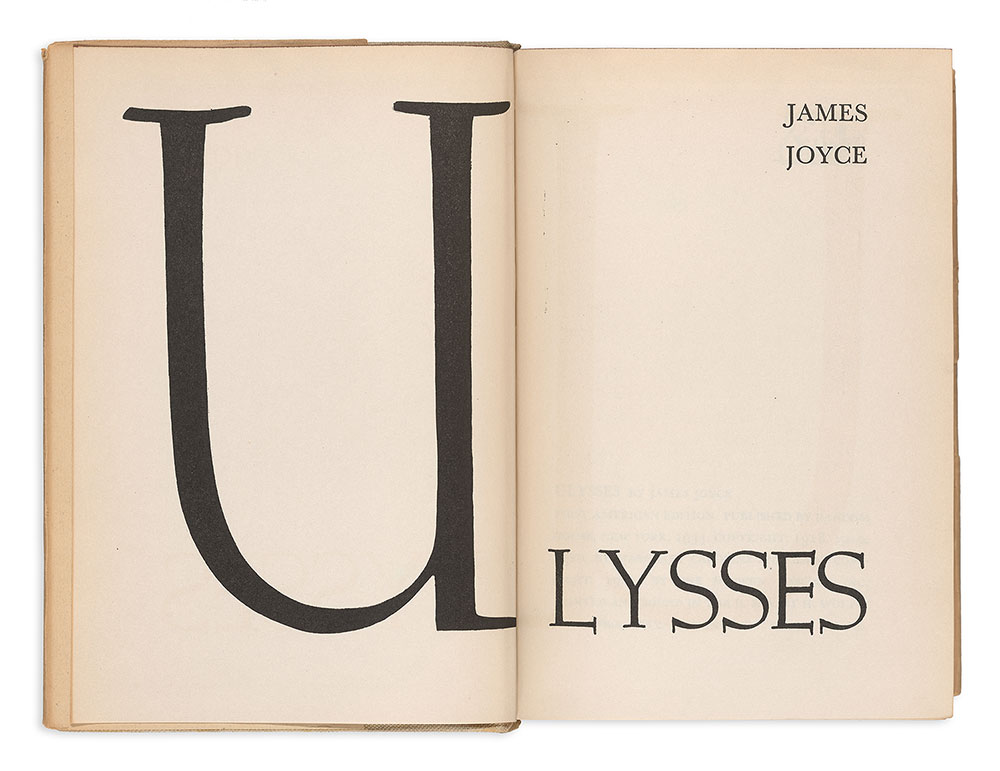

Ernst Reichl

Ernst Reichl, the lead designer at H. Wolff, which manufactured the Random House edition, combined his own elongated lettering on the dust jacket with eighteenth-century Baskerville inside and slightly altered versions of Ernst Rodolf Weiss's brand-new capitals. His innovative work achieved a modern aesthetic that simultaneously evoked the full-page ornate initials associated with medieval page design. Reichl had already won an AIGA award for a book with a double-page title spread, though the lettering had appeared only on the recto. For the double-spread title of Ulysses, however, a large U stands alone on the facing page, serving both as text and image. It became a landmark of modern graphic design.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses

Book design by Ernst Reichl (1900–1980)

New York: Random House, 1934

The Morgan Library & Museum, bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987; PML 135629

Now You Can Read Ulysses

Now You Can Read One of the Great Novels of Our Time—James Joyce’s “Ulysses”

New York: Random House, [1934]

Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University