Ulysses in Paris

Unknown photographer

Sylvia Beach and James Joyce in the doorway of Shakespeare and Company, 8, rue Dupuytren, Paris, 1921.

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

Sylvia Beach

Sylvia Beach (1887–1962) grew up in Baltimore, Paris, and Princeton, settling permanently in France in 1916. She opened Shakespeare and Company, an English-language bookshop in Paris, in 1919. In February 1921 she began helping Joyce find typists for Ulysses and, by April, agreed to bring out the novel herself. Beach published the book eight times between 1924 and 1930, reportedly selling twenty-eight thousand copies. As a US citizen, Beach was briefly interned during the German occupation of France in 1941, the year Joyce died, and her shop never reopened. In her later years, Beach gave George Whitman her blessing to change his bookstore’s name to Shakespeare and Company, which remains in business today.

Paul-Émile Bécat (1885–1960), Portrait of Sylvia Beach, 1923. Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Shakespeare and Company

Sylvia Beach started her imprint Shakespeare and Company in 1921 in order to publish Ulysses (she would issue two other books and one audio recording, all by or about Joyce). In its early days, Shakespeare and Company was primarily a secondhand bookstore and lending library. Beach soon expanded her inventory to feature the latest modernist books and magazines, turning the small shop into a hub for savvy locals, expatriates, and tourists. Joyce met Beach shortly after moving to Paris in June 1920, and he joined the shop’s lending library later that year. The first book he borrowed was apparently The Master Builder by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906).

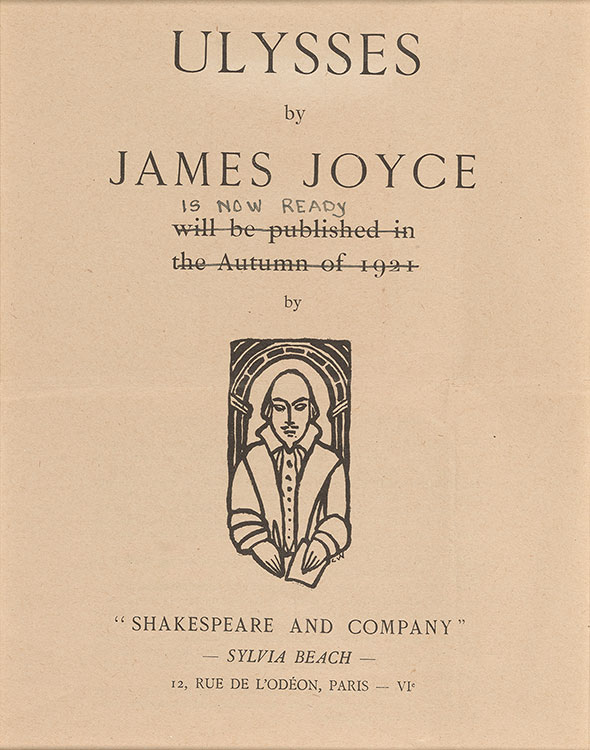

Advertising card for Shakespeare and Company

[Paris: Shakespeare and Company, after 1920]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018: PML 197834

Signboard for Shakespeare and Company

Marie Monnier-Bécat (1894–1976)

Signboard for Shakespeare and Company, Paris, after 1920

Enamel on metal

Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Prospectus for the First Edition of Ulysses

Soliciting subscriptions for Ulysses was imperative for Sylvia Beach to finance the hefty publication. This approach also designated the book a “private edition,” which diminished legal risks. Customers could order one of three versions, priced according to the fineness of their paper; the most expensive version was signed by Joyce. In 1921 and 1922 Beach printed hundreds of circulars such as this one and mailed them to individuals and bookshops around the world. Her forecast of a six-hundred-page book to be published in autumn 1921 proved optimistic. After the novel appeared on 2 February 1922, Beach annotated this circular accordingly: Ulysses was “now ready,” and the page count was 732.

Subscribers' bulletin for Ulysses by James Joyce

Paris: Shakespeare and Company, [1921]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018: PML 197831-32

J. Pierpont Morgan's Nephew Subscribes

Orders for Ulysses began to arrive in Sylvia Beach’s shop soon after she circulated her prospectus in spring 1921. Many early sales were to bookshops, including several in Paris, and to firms that exported books to Europe and America. These customers received what was a modest trade discount in 1922, and they could—and often did—inflate the price thereafter. J. Pierpont Morgan’s nephew Junius Spencer Morgan (1867–1932) ordered his personal copy directly from Beach.

Junius Spencer Morgan’s order form for Ulysses, 1921/22

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Letter of Protest from a Printer

In this letter to Sylvia Beach, a man named Hirchwald—the only English-speaking employee at Maurice Darantiere’s printshop—protests Joyce’s complaint about errors in the latest Ulysses proofs. Joyce was writing and proofing simultaneously, as he told a friend: “[I] am working like a lunatic, trying to revise and improve and connect and continue and create all at the one time.” Hirchwald blames Joyce’s handwritten additions for the errors, reminding Beach that his colleagues cannot read English. Promising to fix these “small nuisances” in his final proofreading, scholars have proven that Hirchwald in fact introduced new errors when correcting his typesetters’ work.

M. Hirchwald

Letter to Sylvia Beach, 11 October 1921

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Getting the Right Blue on the Cover

Tasked with the challenges of typesetting Joyce’s ever-changing text, the printer Maurice Darantiere also faced difficulties related to Ulysses’ cover. Joyce’s long-held superstitions that Greece brought him good luck led him to insist that the book be bound in the colors of the Greek flag—blue and white. Darantiere provided Joyce with sample after sample of blue paper, none of which satisfied the finicky author. Less than a month before publication day, Joyce sent the small Greek flag hanging in Shakespeare and Company to the artist Myron C. Nutting, asking him to identify the right pigment. Darantiere then lithographed the “Greek-flag blue” onto white paper.

Final proof of cover for Ulysses

Lithograph

[Dijon: Maurice Darantiere, 1922]

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Publication Day

On 7 August 1921, Joyce wrote to Harriet Shaw Weaver to announce that he had composed the first sentence of Ulysses’ final episode, adding,“but as this contains about 2500 words the deed is more than it seems to be.” (In fact, the first sentence would be even longer, and the “Ithaca” episode was also far from complete.) Months later, he was still revising the text and checking facts, writing to his aunt, for instance, to make sure “an ordinary person” could climb over the railings at the Blooms’ Eccles Street address. Joyce continued to work on proofs through the end of January 1922.

Superstitious about his birthday, Joyce was determined that Ulysses be ready on 2 February. Few copies were bound on 1 February, but the printers granted Joyce’s wish, dispatching three copies by express mail and, at the author’s insistence, two more on the Dijon–Paris train, which were in his hands by early morning. In her memoir, Sylvia Beach recalled the momentous day: “Here at last was Ulysses. . . . Here were the seven hundred and thirty-two pages ‘complete as written,’ and an average of one to half a dozen typographical errors per page.”

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses

Paris: Shakespeare and Company, 1922

The Morgan Library & Museugift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018, PML 197791

Ulysses Account Rendered

Beach’s earliest surviving record of costs accrued for promoting, printing, and shipping Ulysses was compiled almost six months after the novel’s publication. Joyce’s relentless revisions and additions to the proofs reduced Beach’s initial profits; the printing costs were double what Maurice Darantiere had estimated in 1921. The unusual nature of Joyce’s professional relationship with Beach, who acted at times as his agent, secretary, and friend, is also evident in her bookkeeping, which includes fees for the seventeen-volume edition of Arabian Nights Joyce requested and for Dr. Borsch, the eye doctor Beach recommended to the author.

Sylvia Beach (1887–1962)

“Ulysses Account Rendered” for Shakespeare and Company, Paris, 27 July 1922

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Joyce's Recording of Ulysses

This is one of the two recordings of Joyce’s voice—a reading of John F. Taylor’s speech from the “Aeolus” episode of Ulysses, recited by the author in a Cork accent. Sylvia Beach, who commissioned the disc, had planned to invite journalists to the session, but the producer at the record label His Master’s Voice was not interested in publicity. He foresaw no profit (voice recordings by authors were anomalies in 1924) and insisted the label’s name be kept out of it. Of the twenty or thirty pressings Beach authorized, all but a handful soon broke into pieces. To this day, it remains Joyce and Beach’s rarest “publication.”

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses (pp. 136–137)

78 rpm audio disc

Paris: Shakespeare and Company, 1924

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018: PML 197880

Adrienne Monnier's Déjeuner "Ulysse"

In 1929, fifty kilometers from Paris in the Chevreuse Valley, Adrienne Monnier hosted a luncheon at the Hôtel Léopold to celebrate her publication of the French translation of Ulysses— an enormous undertaking, years in the making. Since Joyce’s arrival in Paris in 1920, Monnier elevated his reputation among prominent French writers. She hosted the first conference on Ulysses in 1921 at her bookstore, La Maison des Amis des Livres, which prompted the first substantial translations of excerpts from the novel. Joyce called her Déjeuner “Ulysse” a “country picnic,” though guests were chartered on a special bus and Monnier had the menu printed as a keepsake. The meal kicked off with paté de Léopold.

Déjeuner “Ulysse”: jeudi 27 juin 1929, Hôtel Léopold, Les Vaux de Cernay

Paris: [Adrienne Monnier] printed by Société génerale d’Imprimerie et d’édition, 1929

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018: PML 197798

Unknown photographer

James Joyce and guests at the Déjeuner “Ulysse”, Les Vaux de Cernay, 27 June 1929

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Édouard Dujardin

The writer Édouard Dujardin (1861–1949), who attended Monnier's Ulysses banquet and signed this copy of the keepsake menu, was credited in France in the late nineteenth century as the innovator of the stream-of-consciousness technique in narrative. Joyce had become familiar with Dujardin's work during his brief stint in Paris in 1902. More than twenty years later, when A Portrait of the Artist as Young Man was published in France, Dujardin became aware of certain similarities in their work—a connection that had also come to the attention of French critics regarding Joyce's version of stream of consciousness employed in Ulysses. Dujardin's career subsequently underwent a renaissance, which he credited to Joyce's fame in France. Joyce himself conceded his debt to Dujardin. In a copy of Ulysses inscribed to the French author, Joyce signed it "the impenitent thief."

Déjeuner “Ulysse”: jeudi 27 juin 1929, Hôtel Léopold, Les Vaux de Cernay

Paris: [Adrienne Monnier] printed by Société génerale d’Imprimerie et d’édition, 1929

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197798