Writing Ulysses: An Endlessly Changing Surface

The manuscript of Ulysses is a palimpsest of Joyce’s restless mind and holds the key to how his imagination worked. While the novel’s structure, based on the Odyssey, and its plotlines were stable, the act of writing for Joyce was filled with excitement and possibility. As well as the story of a day in Dublin, Ulysses is about style in narrative— how many systems can compete in a single page or episode. As Joyce worked, nothing was fixed.

Nothing was arguably fixed even after the book was published. There were slight changes--corrections and new errors--each time Ulysses appeared. An account by the scholar Luca Crispi in 2019 summed up the surviving evidence of Ulysses’ composition: 100+ pages of notes, about 39 handwritten drafts, 1,400+ pages of typescript, approximately 5,000 pages of galley and page proofs, and a fair copy manuscript of 800+ pages. The forms and volume of material related to the novel’s composition led to controversial efforts to establish a definitive text—a task that was not satisfied until the 1984 edition, edited by Hans Walter Gabler. For some scholars, that text was not entirely free from controversy. This section of the exhibition features some of Joyce’s plans and sources for the novel and considers his creative practice in manuscript and proofs through the lens of two episodes: “Sirens” and “Cyclops.”

Man Ray (1890–1976)

James Joyce, 1922

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; 2018.21

© 2022 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (AR), New York / ADAGP, Paris

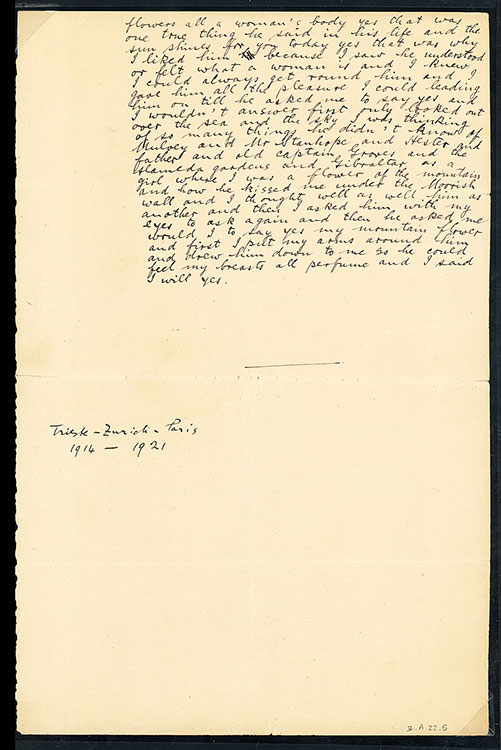

Molly Bloom and Nora's Style

In Ulysses Molly Bloom, the wife of Leopold, comes to life mainly in her husband’s thoughts. Throughout the day he contemplates her affair with a man called Blazes Boylan. Much more than an object of desire and jealousy, however, Molly is also the character who gets the last word. In the book’s final episode, “Penelope,” Molly is not merely breathless but also eloquent, not merely sexually frank but also an engaging narrator and storyteller. Studying Molly’s soliloquy alongside a 1904 letter on view in the gallery from Nora Barnacle to Joyce, one notices a similar lack of punctuation, the sense of pure voice unmediated by irony or craft or literary artifice.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses

Paris: Shakespeare and Company, 1922

The Morgan Library & Museum, bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987; PML 135610

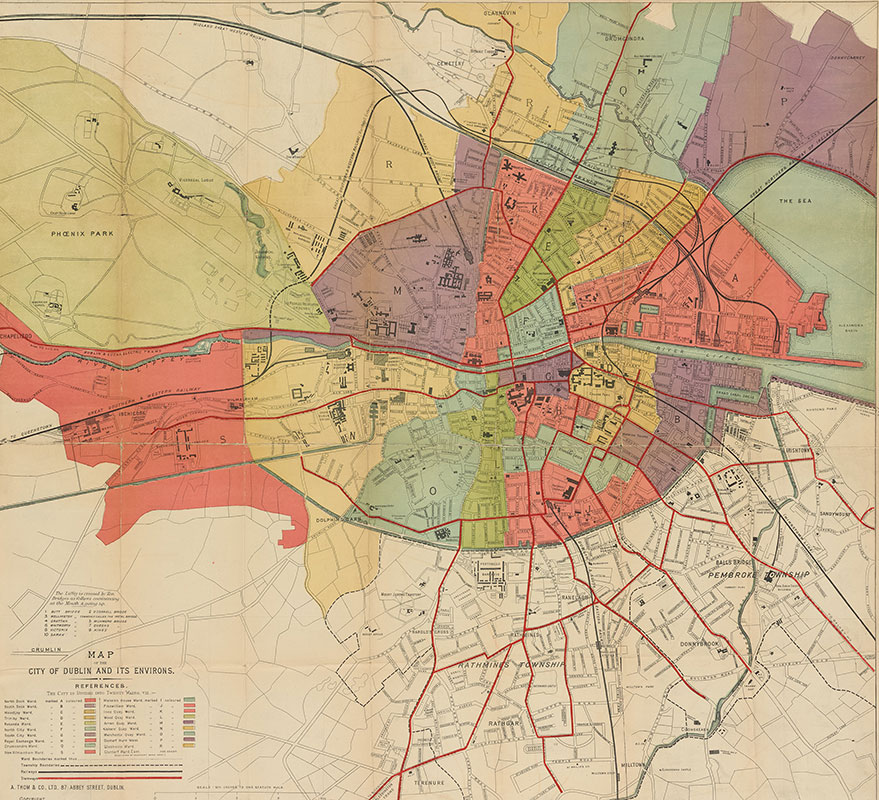

Thom's Dublin Directory

Joyce in exile relied on this residential and commercial directory of Dublin from 1904 to render the intricate urban fabric of Ulysses, which is set that same year. Published annually, Thom’s offers a wide range of information about Dublin, from hackney cab fares to racing calendars and listings of doctors. It contains a detailed street-by-street directory of the city as well as a large folding map. Joyce mined Thom’s for details to include in Ulysses, presenting Dublin with uncanny topographical and historical accuracy. The address 7 Eccles Street, the Blooms’ residence, was listed as vacant in 1904.

Vignette on binding of Thom’s Official Directory of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (Dublin: A. Thom, 1904)

Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University

A. Thom & Co.

Map of the City of Dublin and Its Environs, 1915

Courtesy the General Research Division, The New York Public Library

Writing Ulysses

“In writing one must create an endlessly changing surface . . .”

–James Joyce, from Arthur Powers’s Conversations with James Joyce

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses, manuscript of the first page of the “Telemachus” episode

Zurich, 1917

The Rosenbach, Philadelphia; EL4 .J89UL 922 MS

© The Estate of James Joyce.

While Joyce had a scheme for Ulysses, a structure, he knew what he was doing to that extent, but as he worked on the actual chapters, his mind became increasingly restless and his imagination, increasingly ambitious. So the very act of writing became for him an act of changing of possibility, of excitement, so that he was telling the story of these characters and their day in Dublin, but he was also setting about to create a sort of systems of style and systems of competing narratives, often in a single page, often in an episode, but usually in each episode having a different style. So he constantly revised the text to making many additions and emendations even as the book was being printed, he was making changes, of course, much to the puzzlement, astonishment, and annoyance of the printers.

Ulysses from Beginning to End

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses, manuscript of the last page of the “Penelope” episode

Paris, 1921

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Ulysses begins with the word “stately.” In other words, a word with s, and y, and it finishes with “Yes,” in other words, a word with y, and s. And it is as though the letter s as beginning and ending the book is a sort of curl, or a way of beginning again, and the y with its with its two arms, as it were, up in the air. So that there's a sense that the book curves around itself that as it begins, it ends, and as it ends it begins. And this is part of I think the overall design of the book. I think you can never read too much into the book, that is the sense of every word is a key to another word, or even the way letters are made or even the way the pages are laid out, that all of it is part of a grand design.

The Schema of Ulysses

Joyce created lists and charts to help plan Ulysses. This schema, as Joyce called it, diagrams the novel with respect to each episode’s symbol, color, art, organ, hour, scene, narrative technique, and Homeric correspondences. Joyce first collated notes in this scroll format to help certain writers discuss or translate parts of the work; he also made presentation copies for Harriet Shaw Weaver and Sylvia Beach around the time of the novel’s publication. The extensive Homeric links had been elaborated as he neared Ulysses’ completion, when Joyce sought to unify more motifs across episodes and clarify the structure. He later regretted the document’s unauthorized circulation, believing that it detracted from an appreciation of the novel’s overarching form and substance.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Typewritten schema of Ulysses, with detail

Prepared for George Antheil, Paris, ca. 1924

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197792.1

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Embryological Chart for "Oxen of the Sun"

This is one of two versions of Joyce's diagram for "Oxen of the Sun"--an episode set in a maternity hospital. The near-illegible words track the month-by-month developments of a human fetus, paralleling the metamorphosis of language Joyce explores through pastiche. In a letter to Frank Budgen, dated 20 March 1920, Joyce wrote that he was hard at work on the episode—"the idea being the crime committed against fecundity by sterilizing the act of coition." Joyce related to Budgen a litany of the progression of literary styles he planned to employ, including a Sallustian-Tacitean prelude ("the unfertilized ovum"), early alliterative and monosyllabic English, Anglo-Saxon à la Mandeville, followed by Malory, the Elizabethan chronicle style, Milton, "Latin-gossipy," Burton, Browne, Bunyan, Pepys, Evelyn, Defoe, Swift, Addison and Steele, Sterne, Landor, and Pater, culminating in his identification of English, Irish, American, and Black vernaculars.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Embryological diagram for the “Oxen of the Sun” episode in Ulysses, 1920

James Joyce Collection, #4906, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Music in "Sirens"

Ottocaro Weiss (1896–1971)

James Joyce, Zurich, 1915

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

The “Sirens” episode of Ulysses takes place at 4 pm at the Ormond Hotel on the Quays overlooking the River Liffey. Stephen Dedalus’ father Simon is there, his friend Ben Dollard is there. Leopold Bloom, the main protagonist of the book, enters the dining room. Now what happens in this episode is a sort of apotheosis, for Joyce, of how his father is to be presented in Ulysses. Simon Dedalus comes into the bar. He's not drunk, he's not annoying anybody, he's not a domestic nuisance, he is a man with a beautiful singing voice and everybody wants to hear him. And in this episode, he sings “M’appari” from Martha by Flotow and he’s followed by his friend Ben Dollard, who sings “The Croppy Boy” which is an Irish nationalist ballad. Bloom is in the other room listening to this. [Music begins]

I think this episode shows us more than anywhere else, the importance of music in Ulysses. That is how people are connected. Molly Bloom, Leopold Bloom’s wife, is a singer. Simon Dedalus is a singer. They have known each other for years and it's a very small world of professional and semi professional singers. [Music begins]

The Joyces and O'Sullivans Around the Piano

Unknown photographer

Nora Barnacle Joyce, Marguerite and John O’Sullivan, and James Joyce, Paris, ca. 1930s

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

A Mosaic Piece from "Sirens"

Joyce always carried note pads and stray bits of paper in his jacket. According to the painter Frank Budgen, a friend of Joyce’s, “alone or in conversation, seated or walking, one of these tablets was produced, and a word or two scribbled on it at lightning speed.” This aspect of Joyce’s composition process led Budgen and writer Valery Larbaud to compare Joyce to a Renaissance mosaic artist, patiently fabricating large figures of the saints out of tiny pieces of colored stones.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Manuscript fragment from the “Sirens” episode, Zurich, [1918 or 1919]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; MA 9770

© The Estate of James Joyce.

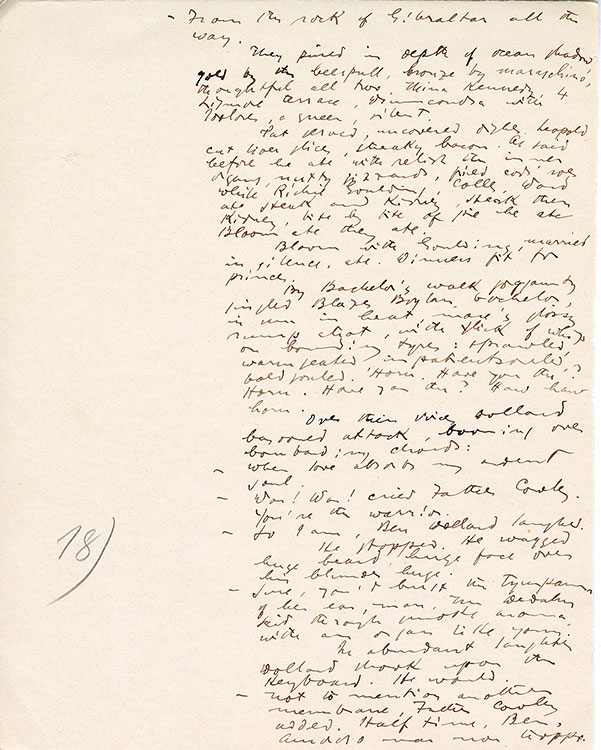

"Sirens": The Fair Copy

This page of “Sirens” is taken from the “fair copy” manuscript of Ulysses—a term used to describe manuscripts created for presentation, rendered in legible handwriting. Joyce prepared this particular manuscript in order to sell Ulysses in installments to the collector John Quinn.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Manuscript page from the fair copy of the “Sirens” episode, Zurich, May 1919

The Rosenbach, Philadelphia; EL4 89ul 922 MS

© The Estate of James Joyce.

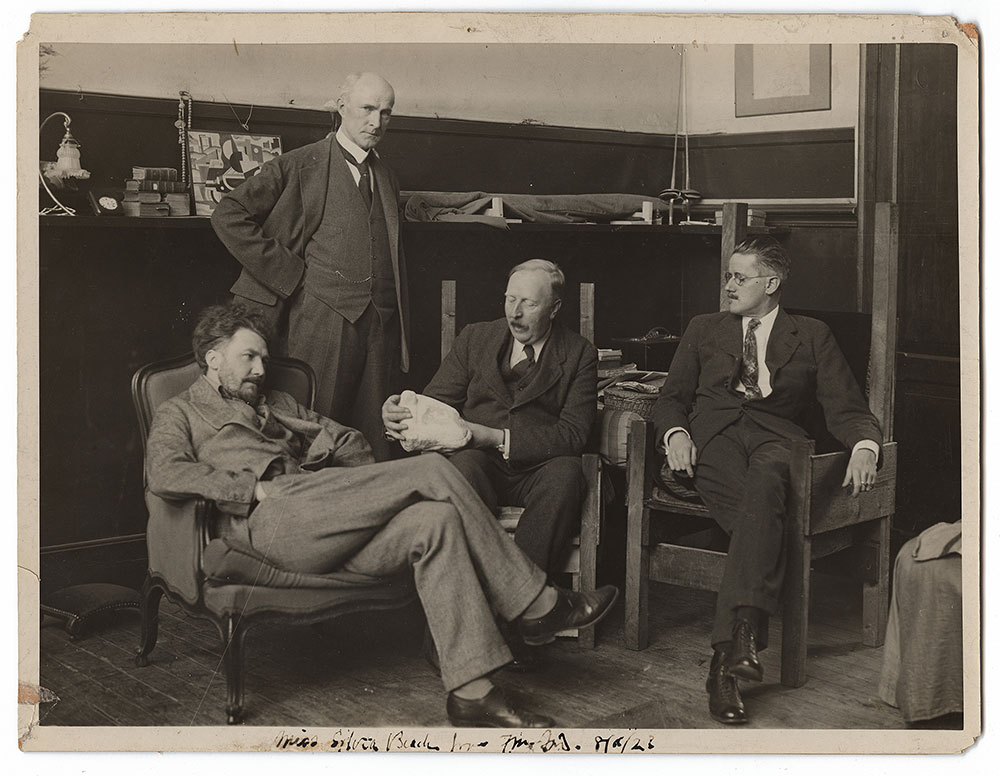

John Quinn

Before his play Exiles was published or performed, Joyce had sold the manuscript to the American modern art collector and lawyer John Quinn (1870–1924), shown here standing with Joyce and the authors Ezra Pound and Ford Madox Ford. As scholars have noted, the sale marked a new source of income for Joyce, who struggled to support his family, and signaled his growing status as an author. Quinn’s investment in Joyce persisted far beyond Exiles: he acted as the attorney for Anderson and Heap in the obscenity case against Ulysses in the Little Review and promoted Joyce to American publishers. Among several other works, Quinn purchased a “fair copy” manuscript of Ulysses as it was being written, enabling Joyce to finish the novel.

Unknown photographer

Ezra Pound, John Quinn, Ford Madox Ford, and James Joyce, Paris, ca. 1923

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Typescript of "Sirens" for the Little Review

Joyce made several typed versions of manuscripts before and after sending fair copies to John Quinn. This page from “Sirens” was sent to printers at the Little Review, an American literary magazine, in 1919 for the novel's initial serialization. Joyce’s handwritten revisions date from 1921, however, as he was beginning to assemble and revise his text for the first edition in Paris.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Typescript from the “Sirens” episode for the Little Review, Zurich, July 1919

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© The Estate of James Joyce.

The Personal Politics of "Cyclops"

Poblacht na h’Eireann (The Irish Republic). The Provisional Government of the Irish Republic to the People of Ireland

[Dublin: s.n., 23 April 1916]

Image reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

The episode known as “Cyclops” takes place at five o'clock in Barney Kiernan’s pub in Dublin. It is, I suppose, the most political episode in Ulysses, and also one of the most stylistically exciting. It was written in 1919, but Joyce did not deal directly in any way with the carnage of the First World War, or the 1916 Easter Rebellion in Dublin, or the ongoing War of Independence against British forces. It is emphatically set in 1904. However, there is a discussion about nations and violence and nationalism and it is, in a way, a veiled response to the very world that Joyce knew being torn apart. He had known Patrick Pierce, who was the leader of the Easter Rebellion, and his friend Francis Skeffington, was murdered on the third day of the Dublin Uprising. But “Cyclops” has its own internal explosions. That even though it is ostensibly set in a pub, with men talking, there are regular interruptions in the style of the episode, where there are parodies and pastiches inserted out of the blue as an exciting intervention of types of discourse that were common in Ireland at the time. So the chapter, stylistically, is hugely adventurous and totally exciting, but in the middle of it, are serious discussions about hatred, about history, and about violence, with Leopold bloom, arguing for a sort of pacifism against the nationalists who are drinking more than he is, and are more heated than he is. But he himself in this episode seems particularly articulate, and particularly serious.

Censoring "Cyclops" in the Little Review

Among several manuscripts and proofs on view related to "Cyclops" are two pages of what is likely the earliest surviving preliminary draft of the episode and a leaf from the 1919 typescript sent to the Little Review, revised two years later. "Cyclops," as Joyce originally wrote it, never appeared in the magazine in its entirety. Following the US Postal Service’s suppression of two Ulysses issues, the editors preemptively censored the first installment of “Cyclops.” One of Joyce’s passages, which alludes several times to erections, was replaced with an asterisk, an ellipsis, and a telling footnote.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Ulysses [the “Cyclops” episode]

Little Review 6, no. 7 (November 1919)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197868.8

© The Estate of James Joyce.

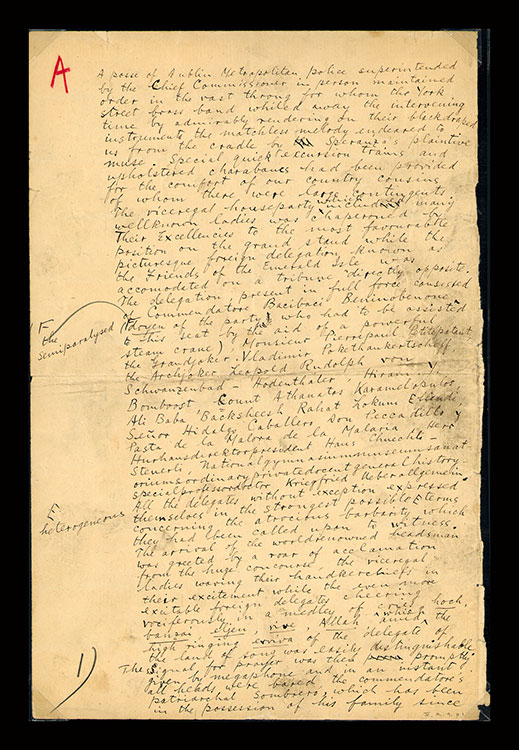

"Cyclops" and Borus Hupinkoff

Joyce reportedly wrote a third of Ulysses in proof—a stage in the publishing process that is typically reserved for minor corrections and additions. The large, eight-page format of French galley proofs on view in the gallery, known as placards, offered ample marginal space to accommodate Joyce’s creative practice. This detail of a "Cyclops" placard pertains to one of the passages that Joyce revised most heavily. In addition to the long marginal inscriptions, Joyce’s note in French, indicated with a red A, instructs the printer to insert two new manuscript pages, one of which is on view adjacent to the placard. The lengthy handwritten addition includes a list of “Friends of the Emerald Isle,” parodic names such as “Commendatore Bacibaci Beninobenone” and “Monsieur Pierrepaul Petitépatant.” Across several stages of the proofs, the dignitaries expanded in number. In a brief note sent to Darantiere's manager, M. Hirchwald, Joyce conveyed another late addition named “Borus Hupinkoff” along with a postscript complaining about imperfections in their typographic character f. A pressman marked his request “trop tard” (too late) and Borus did not appear in editions of Ulysses for sixty years.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Detail of Placard 34 for the “Cyclops” episode in Ulysses

[Dijon: Maurice Darantiere, October 1921]

Houghton Library, Harvard University, part gift of Marian Willard Johnson in memory of Sylvia Beach, and part purchase with funds from the Amy Lowell Fund, 1969; Ms Eng 160.4 (83)

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Manuscript additions to placard 34 for the “Cyclops” episode, Paris, 1921

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© The Estate of James Joyce.

How do you finish a novel as ambitious as Ulysses? As Joyce worked on the final episodes of the book, he also began to transform earlier episodes, he went back and back, hardly ever deleting, mostly adding, and in total excitement, sometimes, with lists of names, he would think of another name to add. There's a parodic list of names called Friends of the Emerald Isle, and they include all sorts of ridiculous people, with ridiculous names. Some of it’s very, very funny, but just as the book was going to press, just as the printers were working on getting it ready, Joyce told him one more name he wanted in the list. The name was “Borus Hupinkoff,” which Joyce thought was tremendously funny, and he sent it off telling the printers exactly where it should go. But it was too late. They wrote back saying, “trop tard,” and that name did not make its way into the 1922 edition of Ulysses. It had to wait until the Hans Walter Gabler edition appeared in the 1980s. So for sixty years, that name was wandering the Earth. It did not make its way into print, but it's part of the extraordinary energy that Joyce put in to completing his book, and then thinking it wasn't complete wanting one more thing, wanting to rewrite to add to amend, completely unsatisfied, no matter how close he was to the end.