Exile

James Joyce’s British passport, issued 1924

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© The Estate of James Joyce.

In October 1904, James Joyce and his companion Nora Barnacle, they left Ireland on their epic journey to Europe. Joyce planned to make a living, teaching English. Finally they settled in the city of Trieste. During the time there, Joyce published his book of poems Chamber Music, he finished his book Dubliners, he wrote his autobiographical novel Stephen Hero, which he later redrafted as Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. And as the First World War began in 1914, he was writing his play Exiles and beginning work on Ulysses. Trieste was for him an exciting place. It was the main port of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He took advantage of its rich cultural life and indeed he was joined by his brother Stanislaus, and we have from Stanislaus’ diaries evidence of their going to the opera every night or going to plays. Trieste was a small city, but unlike Dublin, it was multi ethnic, so to his fascination, he could hear many languages on the streets and as an English teacher, of course, he got to know a cross section of the city's inhabitants. He was passionately engaged, of course, with Ireland's fraught relationship with the British Empire and so, therefore, he understood the fierce arguments going on in Trieste then about the future of Italy, and the future of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Joyce's Lectures on Hamlet

Subscription ticket for James Joyce’s lectures on Hamlet, Società di Minerva, Trieste,

November 1912–February 1913

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

The structure of James Joyce's Ulysses, is based on Homer's The Odyssey and there are many correspondences between the two works. But another text, which is really important for Ulysses, is Shakespeare's Hamlet. In the novel, the young Stephen Dedalus gives a sort of an impromptu lecture in the National Library on Hamlet. And in fact, when Joyce was living in Trieste, he himself gave a number of lectures in the city about Hamlet. And in those lectures, he began to tease out ideas and images that would later appear often transformed in Ulysses.

A Model for Leopold Bloom

When Joyce taught English at the Berlitz School in Trieste, one of his pupils was an older Jewish industrialist named Ettore Schmitz, who published under the name Italo Svevo. He became one of Joyce’s closest friends in the city and a source for the main character in Ulysses, Leopold Bloom. Svevo, like Bloom, married a Gentile and had what Joyce’s biographer Richard Ellmann called “an amiably ironic view of life.” Joyce encouraged his student to persevere as a writer. Svevo’s best-known book, La coscienza di Zeno (Zeno’s Conscience), was published one year after Ulysses. In a 1927 lecture, translated later by Joyce’s brother, Svevo describes the feeling among Triestines “that [Joyce] belonged in a certain sense to us.”

Front and back cover of Italo Svevo (1861–1928), James Joyce: A Lecture Delivered in Milan in 1927 by His Friend. Translated by Stanislaus Joyce (New York: New Directions, 1950)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197843

Greeks Bring Good Luck

Joyce was superstitious about Greece, believing that its citizens (“from noblemen down to onionsellers”) brought him good fortune—so much so, that it would affect Ulysses' book design. Count Francesco Sordina, a Greek aristocrat living in Trieste, enrolled in one of Joyce’s first English classes, elevating his instructor’s standing at the school by recommending the course to other wealthy Triestines. Their friendship endured. After World War One began, Sordina and another nobleman helped Joyce and his family emigrate to Zurich. The author memorialized the day they entered Switzerland by inscribing this book to Sordina: “in gratitude and friendship and in remembrance of 21 June 1915.”

Inscription from James Joyce to Count Francesco Sordina

In, James Joyce (1882–1941), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (London: Egoist Ltd., 1917 [i.e., 1918]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197782

© The Estate of James Joyce.

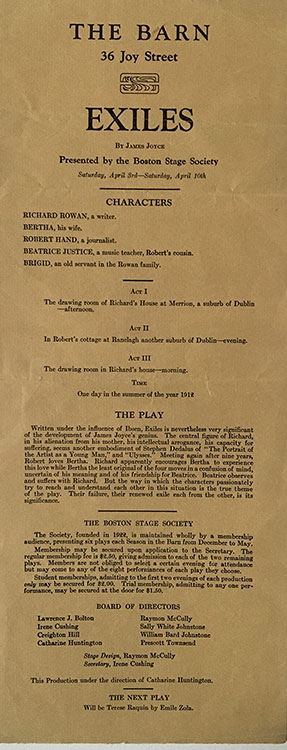

Exiles: A Play in Three Acts

Sexual jealousy and infidelity, themes dramatized in Ulysses, are also portrayed in the play Exiles, Joyce’s least successful work. For years he tried to interest theatrical companies in England, Ireland, and America; there were no takers until August 1919, when Exiles was staged in a German translation in Munich. Joyce summed up the world premiere: “Complete fiasco. Row in theatre. Play withdrawn. Author invited but not present. . . . Thank God.” Exiles was finally performed in English in 1925, at New York’s Neighborhood Playhouse.

This rare broadside program relates to an amateur production mounted the following year by notable figures in the burgeoning gay rights and Little Theatre movements in Boston and Provincetown: Prescott Townsend (1894–1973) and Catherine Sargent Huntington (1887–1987), the play's director. The Boston Stage Society’s repertoire in the 1920s featured European plays by Strindberg, Chekhov, Jean Cocteau, and more obscure modern dramatists. Joyce may not have been aware of this production, nor was he likely compensated.

“Exiles” by James Joyce, Presented by the Boston Stage Society, Saturday, April 3rd–Saturday, April 10th

[Boston: Boston Stage Society, 1926]

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund for the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection, 2021; PML 198668

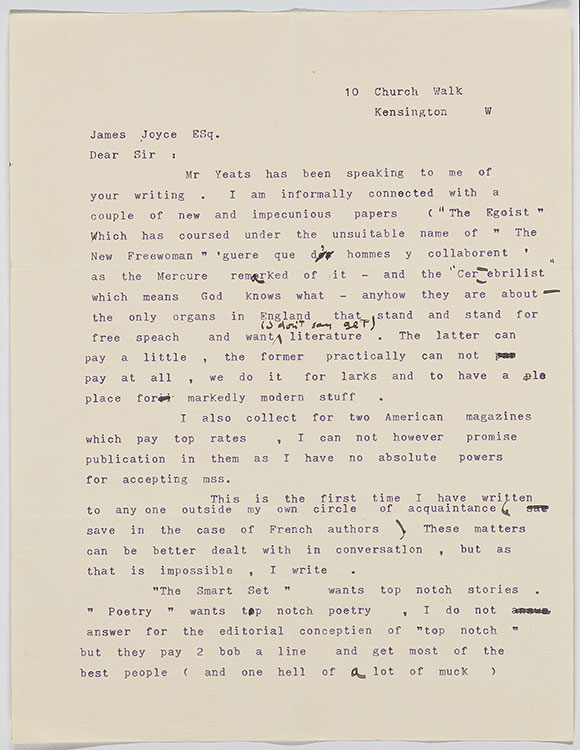

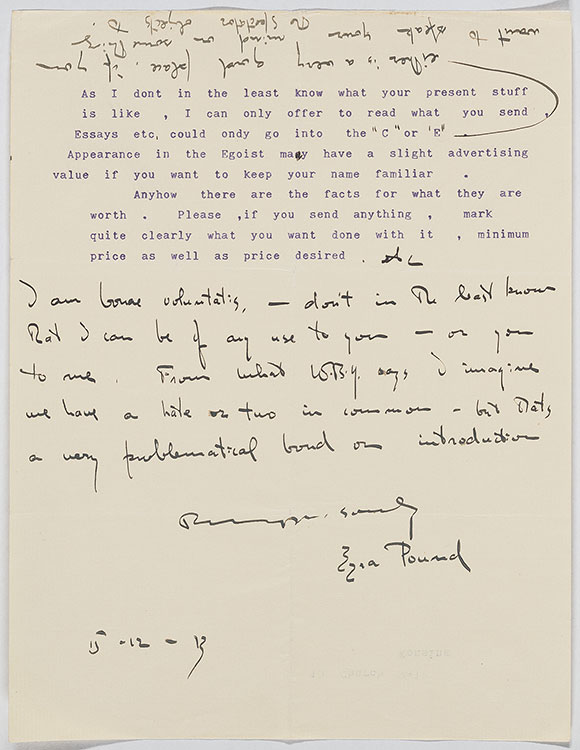

Ezra Pound Introduces Himself

Joyce’s 1903 poem “I Hear an Army” was admired by Irish writer W. B. Yeats, who called it “a technical and emotional masterpiece.” When the poem reappeared in an anthology a decade later, Yeats recommended it to the American poet Ezra Pound. Shown here is Pound’s letter of introduction to Joyce. Before Joyce could answer, Pound wrote again to ask if he could include “I Hear an Army” in the first anthology of Imagist poetry, initially published as a special issue of the American magazine the Glebe. His compliments emboldened Joyce to send Pound Dubliners and the first chapter of his new novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Within a month, thanks to Pound, the serialization of Portrait commenced in the English literary magazine The Egoist.

Ezra Pound (1885–1972)

Letter to James Joyce, 15 December 1913

James Joyce Collection, #4609, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

From POUND/JOYCE: Letters & Essays, copyright ©1967 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

I Hear an Army

James Joyce (1882–1941)

“I Hear an Army”

In, “Des Imagistes: An Anthology.” Edited by Ezra Pound. Special issue, Glebe 1, no. 5 (February 1914)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197777

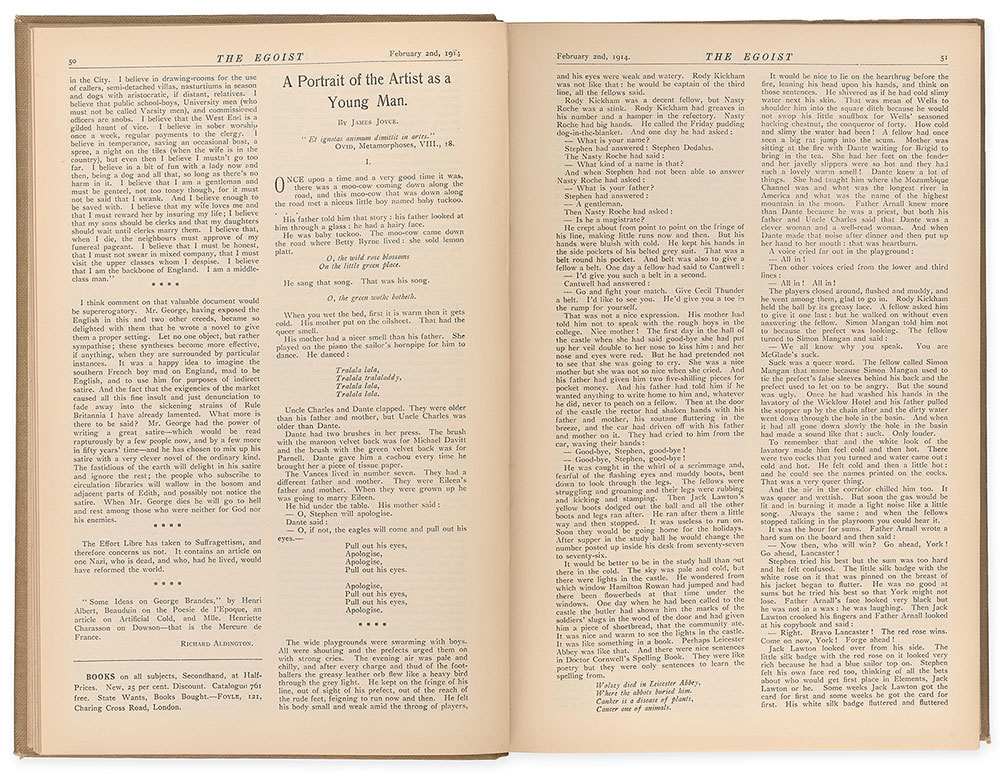

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

“When the soul of a man is born in this country there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight.

You talk to me of nationality, language, religion. I shall try to fly by those nets.”

–James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

James Joyce (1882–1941)

“A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”

In The Egoist: An Individualist Review 1, no. 3 (2 February 1914)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197802

© The Estate of James Joyce.

James Joyce’s first novel is a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and it began in serial form in The Egoist, which was a London magazine, edited by Dora Marsden and Harriet Shaw Weaver. Harriet Shaw Weaver would become very important to the life of Joyce, as she funded him to a large extent, so he could get on with his work in peace. Once the novel began to be serialized, of course, the problems that were always there began about the work’s content, and Harriet Shaw Weaver had to fire several of the magazine's printers, because they would censor words that referred to bodily functions.

The novel is a beautiful book about the growth of a young man, very much based on the life of Joyce himself, his Catholic education with the Jesuits, his home life, the life of his father, his time at University College Dublin. We watch as the style changes in the book from a sort of almost baby talk in the opening sentences to a very, very sort of fragmented ending of the book. And what we have in the book is an account of the growth of the artist who would someday soon write Ulysses.

Harriet Shaw Weaver and her Printers

Harriet Shaw Weaver, who took over the editorial reins of the Egoist shortly after Portrait's first excerpts appeared, confronted resistance from the magazine's printers over subsequent extracts from the novel. Similar to the opposition provoked by Dubliners, some of the language and subject matter in Portrait was viewed as unconventional by pressmen and potentially obscene. Weaver, dedicated to publishing Joyce's text exactly as he had written it, had to fire several of her magazine’s printers for their censoring of words such as “ballocks” and references to bodily functions. Those redactions were made after the printers had produced faithful type settings, however, which allowed the New York publisher B. W. Huebsch to restore the language for the book’s first edition in 1916. Weaver started the imprint Egoist Ltd. in order to publish Portrait in England. Although British printers persisted in their unwillingness to involve themselves in Joyce’s controversial work, Weaver was able to issue her edition by binding sheets that had been printed in America.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

London: Egoist Ltd., 1917 [i.e., 1918]

Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987; PML 135606