The Wake: Joyce's Later Life

Joyce’s struggles to publish Ulysses ended in the 1930s. In response to Judge Woolsey’s 1933 ruling in New York, the author wrote, “Thus one half of the English speaking world surrenders.” When the novel was at last released in England in 1936, he reportedly told friends, “I have been fighting for this for twenty years. . . . Now the war between England and me is over, and I am the conqueror. . . . We’ll see how the Irish will take it now.”

Two years after the first edition of Ulysses, Joyce began writing the radical novel Finnegans Wake. Living in Paris, London, and Zurich, he enjoyed financial rewards due to Ulysses’ success, particularly in America. He twice graced the cover of Time magazine, and when he and Nora married in London in 1931, photographers snapped their picture. The women who had facilitated his publishing career--Margaret Anderson, Harriet Shaw Weaver, and Sylvia Beach--were largely superseded by European and American men; Paul Léon now played the role of friend and business manager. The last decade of his life was also marked by the death of his father, a severe decline in his eyesight, and concern for his daughter Lucia’s mental health. Finnegans Wake was finally published in 1939. As the Second World War began, Joyce and his family again sought refuge in Zurich, where the author died from a perforated ulcer in 1941.

Patrick Tuohy (1894–1930)

Portrait of James Joyce, ca. 1924

Oil on canvas

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

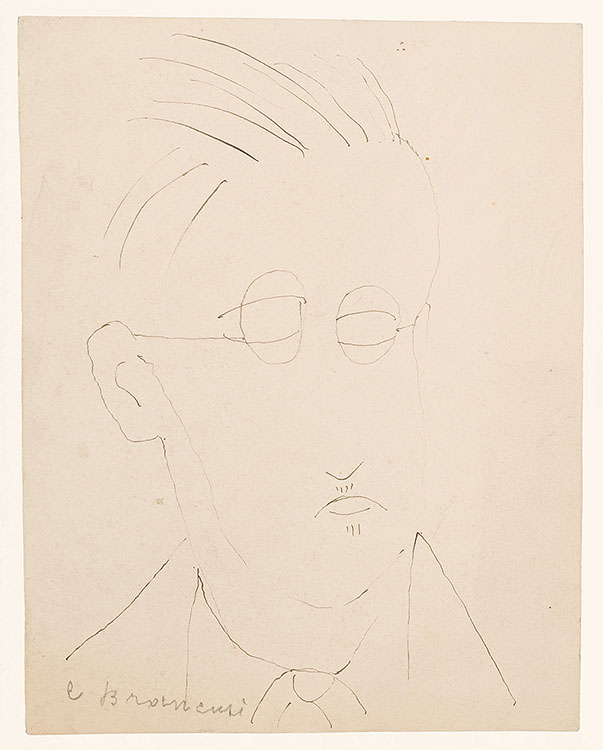

Brancusi's Portrait of Joyce

Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957)

Portrait of James Joyce, 1929

Graphite

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© Succession Brancusi - All rights reserved (ARS) 2021

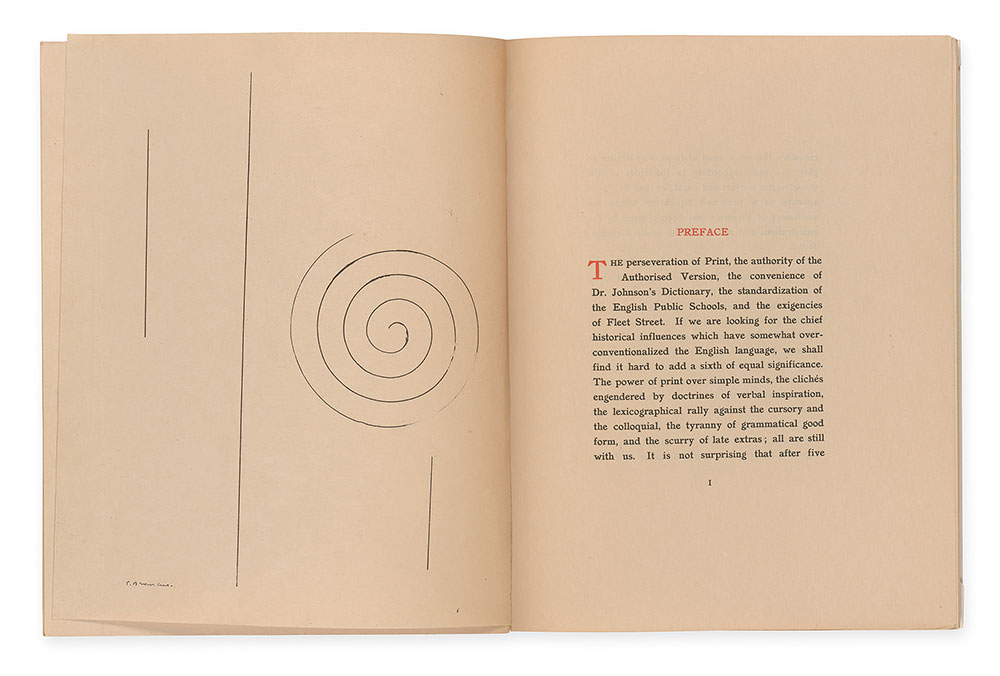

Brancusi's Symbol of Joyce

Constantin Brancusi, a Romanian-born artist in Paris, created several portraits of Joyce. They were commissioned by the American expatriates Harry and Caresse Crosby for their limited edition of excerpts from Finnegans Wake. Rather than use a likeness for the frontispiece, Caresse Crosby chose a spiral design by Brancusi, who called it “Symbol of James Joyce.” It was identified in the Crosbys' book, however, as “Portrait of the Author.” Reportedly, when Joyce’s father saw Brancusi’s image, he remarked,“Jim has changed more than I thought.” Brancusi later explained the cryptic image to the painter Jacques Hérold, noting,“Joyce is like that: he departs from one point, and you’ll never meet him again.”

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Tales Told of Shem and Shaun

“Symbol of James Joyce” by Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957)

Paris: Black Sun Press, 1929

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197815

© Succession Brancusi - All rights reserved (ARS) 2021

Finnegans Wake

Joyce devoted seventeen years to writing Finnegans Wake—a novel about a single night, composed in a style he described as “gliding and unreal as is the way in dreams.” Despite the presence of characters and plot, the Wake defies all other conventions of narrative. It is an assemblage of puns, riddles, and myths—derived from more than sixty languages—that begins and ends in the middle of the same sentence. By 1936 Joyce said that the book had become “more real to [him] than reality, and everything has led to it.” The work’s serialization and stand-alone publications of excerpts often elicited perplexed or negative responses from critics. Joyce considered it his greatest work. The copy shown here is an advance copy of the novel, bound in printed paper-covered boards bearing the final dust jacket design–one of the few known to survive.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Finnegans Wake [Advance Copy]

London: Faber and Faber, 1939

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197823

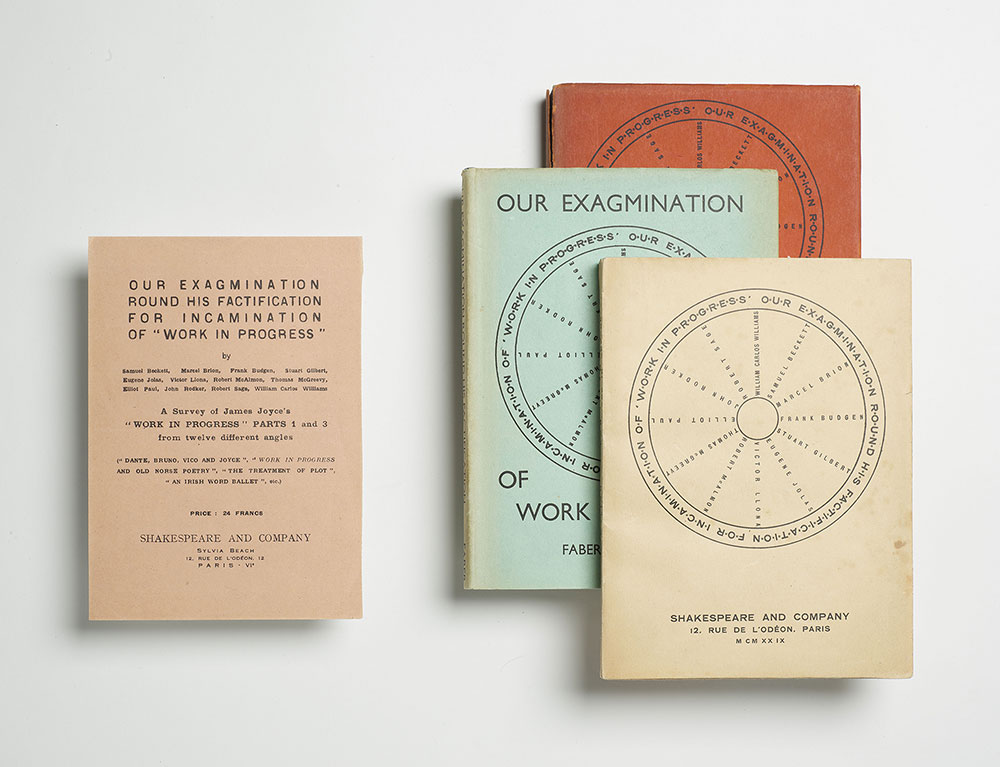

Samuel Beckett and Our Exagmination

The first publication in a book by Samuel Beckett, future playwright of Waiting for Godot, was an essay in this anthology that Joyce supervised and designed. The collection, which also includes texts by William Carlos Williams and Robert McAlmon, sought to interpret and defend Joyce’s work in progress Finnegans Wake. Beckett had met Joyce soon after moving from Dublin to Paris to teach at the École normale. Joyce welcomed him into the family and sometimes used him as a research assistant and secretary. Beckett later recalled that, when he was taking dictation for Finnegans Wake, he once mistakenly recorded Joyce’s response to a noise outside. When Beckett read the passage back to the author, Joyce noted the gaffe and said,“Let it stand.”

Samuel Beckett (1906–1989) et al.

Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of “Work in Progress” [with Prospectus and two other editions]

Paris: Shakespeare and Company, 1929

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197816-19

© The Morgan Library & Museum

Recording Anna Livia Plurabelle

Joyce’s recording of the “Anna Livia Plurabelle” episode from Finnegans Wake was commissioned by the linguistic psychologist C. K. Ogden, who was translating the text into his invented language, called Basic English. The record drew attention in the press; it aired on the BBC and was sold at a prestigious London music store. T. S. Eliot used it as a cross-promotion for the publication of “Anna Livia Plurabelle” in his Criterion Miscellany pamphlet series. Due to the decline in Joyce’s eyesight, photographic enlargements of a printed edition were kept on hand in the recording studio. The letters were not big enough, however, and Ogden reportedly stood by Joyce, whispering into his ear the author’s own words.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Anna Livia Plurabelle

78 rpm audio disc

Cambridge: Orthological Institute, [1929]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197873

Lucia Joyce

Unknown photographer

Lucia Joyce, Paris, 1925

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Lucia Joyce, the daughter of James Joyce and Nora Barnacle, was born in 1907 and died in 1982. She had a nomadic upbringing, moving between Trieste, Zurich, and Paris, where she studied dancing. She was tall, she was graceful, and as a dancer, she developed an individual style. She gave several performances between 1926 and 1929 and the Paris Times wrote about her, “Lucia Joyce is her father's daughter—she has James Joyce’s enthusiasm, energy, and a not yet determined amount of his genius.When she reaches her full capacity for rhythmic dancing, James Joyce may yet be known as his daughter's father.”

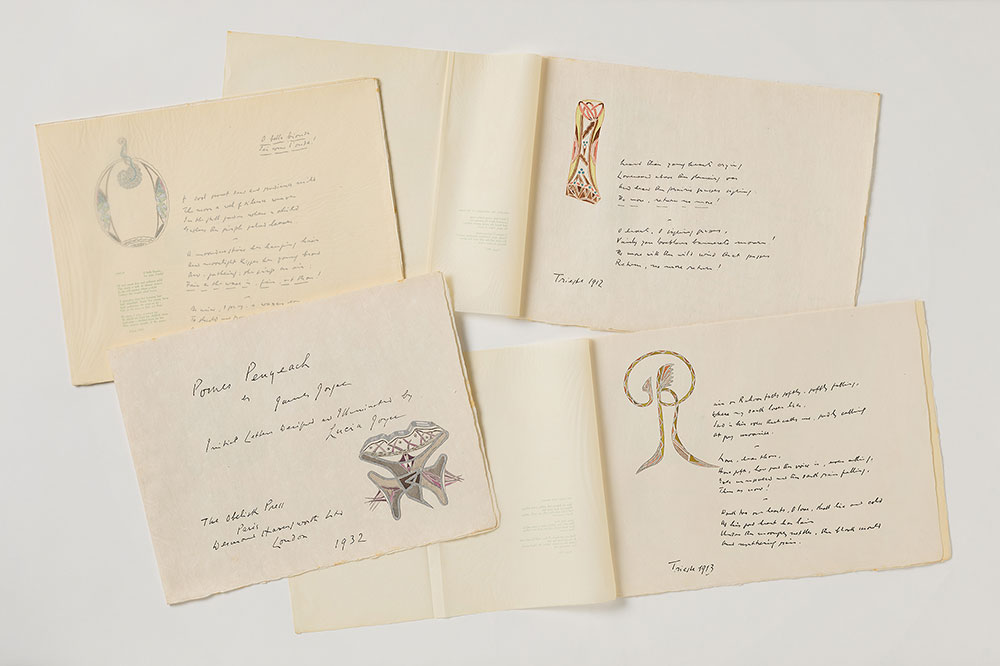

In 1929, however, Lucia decided to give up dancing and she began to create decorative alphabets and designs, sometimes for her father's work. She created an edition of James Joyce's poems, Pomes Penyeach which was referred to simply as Lucia’s book and she also found a publisher for her illustrated, Chaucer A.B.C. in 1936. In 1934, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and for many years she underwent treatment. From 1950 until her death, she lived at St. Andrews Hospital in Northampton in England.

Lucia Joyce in Ostend

Unknown photographer

Lucia Joyce, Ostend, 1924

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Pomes Penyeach: "Lucia's Book"

When Joyce pressed Ezra Pound for his opinion of the verse Joyce had written since Chamber Music, Pound was dismissive: “They belong in the bible or in the family album with the portraits.” This luxurious publication, featuring ornate lettering by Lucia Joyce, to some extent follows Pound’s directive, as a father-daughter collaboration formatted like a scrapbook. Twenty-five copies were printed. The edition, which Joyce referred to simply as “Lucia’s book,” came about through his many attempts to interest publishers in Lucia’s work. Obelisk, the Paris publisher of Pomes, eventually brought out her illuminated Chaucer A.B.C. in 1936.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Pomes Penyeach

Illuminations by Lucia Joyce (1907–1982)

Paris: Obelisk Press; London: Desmond Harmsworth, 1932

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197875

© The Estate of James Joyce.

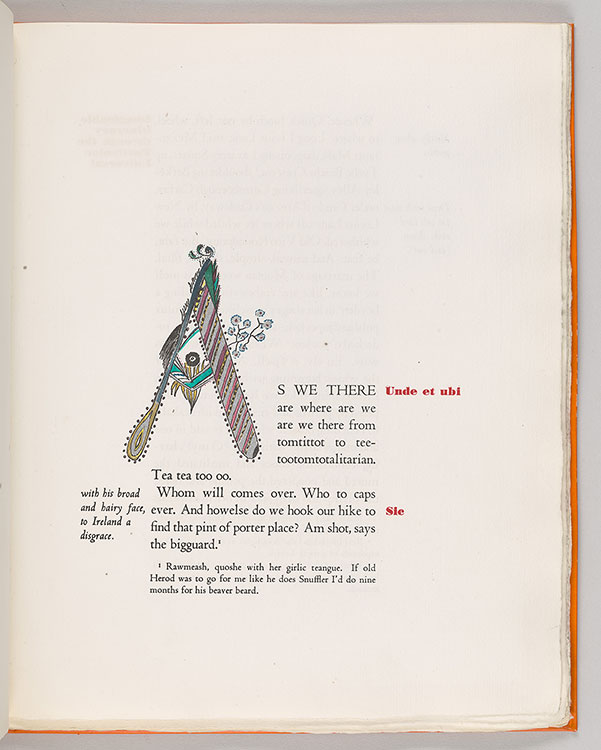

Storiella as She Is Syung

Limited editions of fragments from Finnegans Wake reflect Joyce’s increased attention to his books’ design. Often, before he had secured a contract, he had fully conceived the publication as an object: detailed instructions for the binding color, typography, and page design accompanied his manuscripts. Anticipating public resistance to the texts, he also requested room for contextual front matter. Delays to this fine-press edition of the “Storiella” fragment were caused by Joyce’s complex layout. In addition to his daughter's elaborate initial A, it includes medievalist rubrics, footnotes, diagrams, and marginal texts.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Storiella as She Is Syung

Illuminated initial by Lucia Joyce (1907–1982)

[London]: Corvinus Press, 1937

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197877

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Lucia Joyce's Cover for The Mime

James Joyce (1882–1941)

The Mime of Mick Nick and the Maggies

Cover illustration by Lucia Joyce (1907–1982)

The Hague: Servire; Paris: Messageries Dawson, 1934

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197820

Joyce's Eyeglasses

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen Dedalus breaks his glasses on the school’s cinder path. For this he is unfairly reprimanded, leaving him “burning with shame” in front of his classmates. Stephen’s fuzzy perception of the schoolyard without corrective lenses—“the fellows seemed to him smaller and farther away . . . and the soft grey sky so high up”—evokes Joyce’s lifelong issues with his eyesight. From 1907 Joyce experienced bouts of iritis and would eventually develop glaucoma, cataracts, and nebulae. He underwent a series of painful surgeries and by the end of his life was blind in one eye with greatly reduced vision in the other.

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen Dedalus breaks his glasses on the school’s cinder path. For this he is unfairly reprimanded, leaving him “burning with shame” in front of his classmates. Stephen’s fuzzy perception of the schoolyard without corrective lenses—“the fellows seemed to him smaller and farther away . . . and the soft grey sky so high up”—evokes Joyce’s lifelong issues with his eyesight. From 1907 Joyce experienced bouts of iritis and would eventually develop glaucoma, cataracts, and nebulae. He underwent a series of painful surgeries and by the end of his life was blind in one eye with greatly reduced vision in the other.

James Joyce’s Eyeglasses

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Joyce's Calling Card and Cane

Joyce wrote this note to George Pelorson (the pseudonym for Georges Belmont [1909-2008]) on his calling card in Ulysses-blue ink. It was enclosed with a copy of the 1939 Official Dublin Guide. The book had just been sent anonymously to Joyce’s address and he assumed a friend of his schoolmate Constantine Curran was responsible. Pelorson, a good friend of Beckett’s, was a frequent companion of Joyce toward the end of the 1930s. When he received the note and enclosure, Pelorson was working on an article on Finnegans Wake for Revue de Paris. Explaining that the Dublin guide is à propos of nothing, Joyce asks him to look at two “curious” pages where, unsurprisingly, the author is mentioned. Among other references, the guide highlights number 41, Brighton Square, Rathgar, as the birthplace of the world-famous writer.

James Joyce's Calling Card, bearing letter to George Pelorson, [2 July 1939]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; MA 9768

James Joyce’s Cane

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Augustus John's Portrait of Joyce

Augustus John (1868–1961)

Portrait of James Joyce, ca. 1930

Graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum; 2022.16

© Augustus John / Bridgeman Images

Joyce and Paul Léon

Boris Lipnitzki (1887–1971)

James Joyce and Paul Léon, Paris, 1934

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Mme. Paul L. Léon, 1956; MA 1764.5

© Boris Lipnitzki / Roger-Viollet