Joyce's Youth

Constantine P. Curran (1886–1972)

James Joyce, Dublin, 1904

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

James Joyce was born in Dublin in 1882. He was the eldest of a large family, a family at the time he was born was a prosperous family. His father had a job and owned property and got rents from the property. But slowly, his father began to mortgage the properties. His father was a drinker, his father was a waster, and so the family declined and often moved house with bailiffs often in pursuit. And this was his childhood. The city too, the city of Dublin, where he was brought up, was not a prosperous city, it was a city also in decline. There was really no manufacturing base, and there were many living in slums without proper sanitation. And Dublin famously had the largest Red Light District in Europe. And in his book Ulysses, Joyce, James Joyce, would portray these surroundings in detail, he said to a friend that it were so complete, that if the city one day suddenly disappeared from the earth, it could be reconstructed out of my book.

In University College Dublin, Joyce developed literary interests, but he disliked the prevailing insularity and cultural nationalism, which was growing in Ireland. And this really was part of his decision to leave Ireland in 1904. And a few months before he left the city, he met Nora Barnacle who would become his companion for life. And the first date they had was on the 16th of June 1904, and that was the day on which he said his novel, Ulysses.

Joyce's father, John Stanislaus Joyce

Patrick Tuohy (1894–1930)

Portrait of John Stanislaus Joyce, ca. 1923–24

Oil on canvas

The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

We cannot overestimate the importance of James Joyce's father in the making of the novel Ulysses. Joyce wrote about him, “I got from him his portraits, a waistcoat, a good tenor voice, and an extravagant licentious disposition.” In the novel Ulysses, Simon Dedalus is a version of John Stanislaus Joyce, James Joyce's father. And obviously the father was a very bad provider for his family, but what Joyce did in the novel was he showed him as a figure on the streets, as a popular man. He was leaving his daughters penniless, but he was also witty. He was good company and of course, he had a beautiful tenor voice that soars especially in the Sirens episode of the novel. About his father's influence on the novel Ulysses, Joyce told a friend, “The humor of Ulysses is his. Its people are his friends. The book is his spittin’ image.”

Joyce's mother, May Murray Joyce

Unknown photographer

James Joyce with his mother, father, and maternal grandfather, 1888

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

Music was really important in the Joyce family. Joyce's mother, May Murray, she came from a musical family, and a friend of her sons remembered her as a frail, sad faced, and gentle lady, whose skill at music suggested a sensitive, artistic temperament. She, from an early age, took piano and voice lessons at school, run by two of her mother sisters beside the River Liffey. And of course, this house became the house of the story, The Dead, and these women became the women who give the party in The Dead. In Ulysses, May appears as, in the Cersei episode, as the ghost of May Goulding. Between 1881, when she was twenty-two, and 1893, May Murray had ten children and three miscarriages. She died of cancer at the age of forty-four. Joyce was summoned back from Paris to her deathbed, an event that would haunt the early episodes of Ulysses.

University College Dublin

Unknown photographer

James Joyce in his Royal University graduation gown , 1902

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York

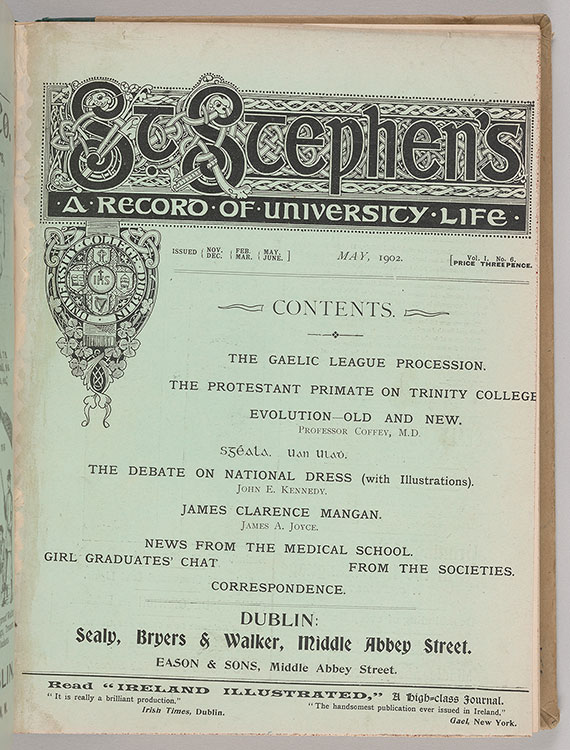

"Planetary Music"

Joyce’s classmates started the magazine St. Stephen’s during his senior year at University College, then part of the Royal University of Ireland. Though independently run, the publication was at the mercy of administrative oversight. Joyce’s submissions of poems, stories, and essays were rejected by the editors or censored by school authorities, with the exception of a piece on the Irish poet James Clarence Mangan (1803–1849). In the essay, Joyce writes, “The philosophic mind inclines always to an elaborate life—the life of Goethe or of Leonardo da Vinci; but the life of the poet is intense—the life of Blake or of Dante—taking into its centre the life that surrounds it and flinging it abroad again amid planetary music.”

St. Stephen’s: A Record of University Life 1, no. 6 (May 1902)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Mr. And Mrs. Robert D. Graff, 1975; PML 65946

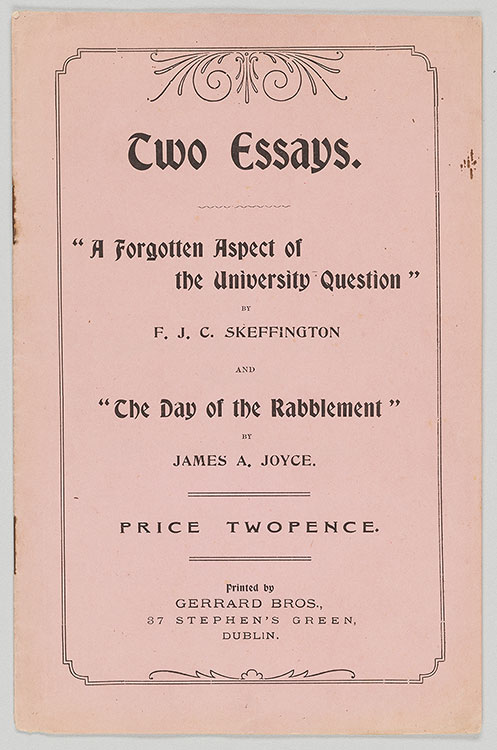

The Day of the Rabblement

Joyce became interested in contemporary drama while at university. He praised naturalist plays for their acceptance of life “as we see it,” and people “as we meet them.” The Irish Literary Theatre, spearheaded by the writers W. B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, was by then exclusively devoted to Irish plays. Joyce’s essay “The Day of the Rabblement” disparaged the project for its lack of cosmopolitanism. One pronouncement points to his life’s trajectory: “A nation which never advanced so far as a miracle-play affords no literary model to the artist, and he must look abroad.” When his school’s magazine refused to print the essay, Joyce and Francis Skeffington, whose submission had also been rejected, self-published this pamphlet.

F. J. C. Skeffington (1878–1916) and James Joyce (1882–1941)

Two Essays: “A Forgotten Aspect of the University Question” and “The Day of the Rabblement”

Dublin: [printed for the authors by] Gerrard Bros., 1901

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197770

A Young Poet

In the years immediately following Joyce’s graduation, his poems began to appear in English and Irish publications, such as the Venture and Dana. Joyce had hoped that Dana would instead accept a piece of prose titled “A Portrait of the Artist.” He reportedly cornered the magazine’s coeditor John Eglinton at his day job at the National Library and stood by while Eglinton read the piece. Eglinton recollected that he passed it back to Joyce, saying it was “incomprehensible.” According to Joyce, the Dana editors had admired the style but could not abide the references to sex. Both Dana and a supercilious librarian named John Eglinton appear in Ulysses.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

“Song”

In Dana: An Irish Magazine of Independent Thought 1, no. 4 (August 1904)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197772

The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature

Cover illustration by Walter Bayes (1869–1956)

London: John Baillie, 1905 [i.e., 1904]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197773

© The Estate of James Joyce.

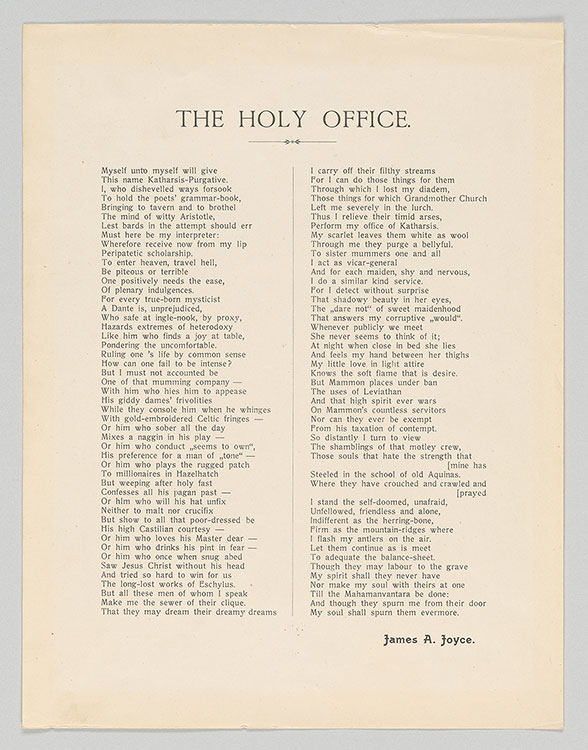

The Holy Office

Joyce composed The Holy Office shortly before he left Dublin in fall 1904. Titled after the Catholic organization that ruled on matters of heresy, the poem attacks the Irish literati— including several writers who encouraged Joyce in his career, such as W. B. Yeats and George Moore. When nobody would print The Holy Office, Joyce self-published it as a broadside, but he could not afford to pick it up before leaving Ireland. The printers eventually destroyed the sheets. After settling in Trieste in 1905, Joyce printed one hundred copies at the city’s most famous stationer. He sent half the edition to his brother Stanislaus in Dublin, instructing him to distribute the broadside to specific friends and writers, some of whom Joyce targeted in the poem.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

The Holy Office

[Trieste: printed for the author by L. Smolars, 1905]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197771

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Chamber Music

There is a young boy named Joyce, who may do something.

He is proud as Lucifer and writes verses perfect in their technique.

—George Russell

The influential critic and poet Arthur Symons met Joyce in 1902. Like other well-known writers, such as W. B. Yeats and George Russell, Symons praised Joyce’s poetry for its beauty and audacity. Eager to assist, Symons sent Joyce’s Chamber Music manuscript to many publishers, though all of them turned it down. By the time Elkin Mathews agreed to print the book, Joyce was more invested in writing fiction. His brother Stanislaus sequenced the poems, though Joyce later claimed he had devised the order himself as a carefully constructed piece of music.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Chamber Music

London: Elkin Matthews, 1907

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197774-75

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Out by Donnycarney

Adolph Mann (1874–1941)

Out by Donnycarney: Song, Words by James Joyce

Cincinnati: John Church, 1910

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund for the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection, 2018; PML 197954

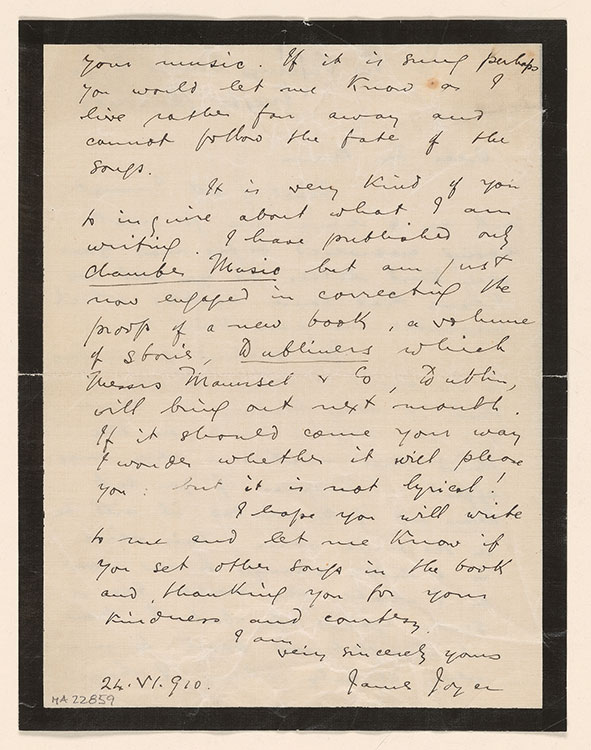

Joyce's letter to a composer about Dubliners

This letter to Adolph Mann (1874–1941)—one of many composers to set Joyce’s poems to music—dates from 1910. Joyce’s musicality (he had pondered a career as a singer) is reflected in his brief, though nuanced, evaluation of Mann’s composition. As the letter indicates, Joyce is much more interested in the proofs he is revising for the imminent publication of Dubliners, a book of short stories. His optimism about Dubliners would soon vanish. The process of publishing it would be drawn out for four more years, primarily because Joyce would not consent to editors’ and printers’ demands for changes.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Letter to Adolph Mann

24 June 1910

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund for the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection, 2018; MA 22859

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Gas from a Burner

Joyce was visiting Ireland when a second publisher reneged on their agreement to bring out Dubliners. The printer pulped the book, anticipating charges of libel and obscenity. Joyce responded with this satiric poem, which he later self-published as a broadside. The narrator, a printer-publisher, traces his shifting reactions to Joyce’s short stories: from initial neutrality to recoil upon seeing the work typeset, followed by patriotic self-righteousness and fear for his soul if he were to print actual placenames in Dublin. The narrator decides to burn the edition and, as a penance, to have his buttocks anointed with Dubliners’ ashes.

After the book’s destruction, a distraught Joyce had visited his father, whose advice was to “buck up, take back the [manuscript] and find another publisher.” Joyce left Ireland that night and never saw his father or homeland again.

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Gas from a Burner

[Trieste: printed for the author, 1912]

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197778

© The Estate of James Joyce.

Dubliners

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Dubliners

London: Grant Richards Ltd., 1914

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197779

James Joyce’s first book of fiction was a book of stories called Dubliners. He began to compose the stories in Dublin in 1904 when he was twenty-two and he finished the last one, The Dead in Trieste in 1907. He wrote to a publisher about the style of the book and his ambition for it, “My intention was to write a chapter of the moral history of my country, and I chose Dublin for the scene, because that city seemed to be the center of paralysis. I have written it for the most part in a style of scrupulous meanness.”

Joyce had very bad luck with publishers, who refused to publish the book for various reasons, including that some of the descriptions were far too frank for the Dublin of the early twentieth century. The book was finally published in June 1914.