Stop 33. East Room

Jesse Erickson, Astor Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

The East Room is an architectural masterpiece designed to store and protect valuable volumes. This was the principal space Morgan used for entertaining groups and for sharing the works in his collection. Originally, Charles Follen McKim planned a single tier of bookcases to circle this room. But Morgan’s collections grew even as his Library was being built and two additional tiers were added.

Much of Pierpont Morgan’s original rare book collection is still shelved here, including early Bibles; first editions of Copernicus, Galileo, and others; and classics of French and American literature. The room holds eleven thousand volumes, only a fraction of the museum’s collection of more than one hundred thousand printed books. The majority of the rare books collection is now stored in a vault built as part of the Renzo Piano expansion.

Stop 34. Secret Staircases

Philip Palmer, Robert H. Taylor Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts

Charles McKim thought of everything in his design for Morgan’s Library—including a clever mechanism for reaching the upper balconies. On the ground floor, some of the bookcases near the entrance doors have brass handles. These cases are designed to pivot, revealing secret spiral staircases behind them that lead to the second and third tiers. These pivoting bookcases are used by librarians and curators when they remove works from the bookshelves for use by researchers or for display in an exhibition.

There is also a secret room concealed behind a bookcase in the southwest corner. The case pivots to reveal a small closet lined with deep shelves for storing the oversized volumes in Morgan’s collection. This space also has a “book elevator” which was used by librarians to transport heavy volumes safely from the upper tiers.

Stop 35. The Ceiling

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

The ceiling that soars above the bookshelves in this grand room is a complex creation. At the center is a large lay light, which was intended to let natural light into the room. It is surrounded by a cove ceiling joining it to the walls. The cove contains lunettes separated by spandrels, offering abundant surfaces for painted and stuccoed decoration.

Charles Follen McKim recruited the artist Harry Siddons Mowbray to develop the decorative program for the ceiling. Morgan, McKim, and Mowbray had been involved in the founding of the American Academy in Rome. All three had a deep appreciation of Renaissance culture that strongly influenced their vision.

Mowbray had carefully studied the great Roman villas and their interior decorative schemes, including their use of gold and stucco. For the lunettes, he chose reclining female figures representing the arts and sciences, based on sixteenth-century models. These alternated with portraits of male architects, painters, printmakers, philosophers, and others, from antiquity to the Renaissance, whom Mowbray selected to represent the leading contributors to Western civilization. To the right of the entrance is William Caxton—the first English printer. Originally, a lunette with Johannes Gutenberg represented the field of printing, but Morgan had recently acquired a collection containing thirty works by Caxton and so Gutenberg’s portrait was replaced.

Mowbray completed the ceiling design by placing the twelve zodiac signs in the spandrels. The zodiac was an important part of Renaissance culture, but it also had personal significance for Morgan, who was a member of a private dining association known as the Zodiac Club.

Stop 36. Triumph of Avarice Tapestry

Woven by Willem de Pannemaker (Flemish, ca. 1510–1581), after a design by Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Flemish, 1502–1550)

1534–36

Wool, silk, and gilt-metal wrapped thread

12 x 24 feet (4.43 x 15 m)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1906

Austėja Mackelaitė, Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator

The Triumph of Avarice is the only surviving tapestry from a series depicting the seven deadly sins that once belonged to the English king Henry VIII. The series was designed by Netherlandish artist Pieter Coecke van Aelst and woven with gilt-metallic thread in the Brussels workshop of Willem de Pannemaker. The king’s set was likely the first weaving of that series, dating to circa 1535.

As recounted in a sixteenth-century description, the Triumph of Avarice is full of historical references to the consequences of greed. At left, the winged and taloned Avarice emerges from Hell in a chariot drawn by a griffin; in her wake are Death, Betrayal, Simony (or the selling of pardons), and Larceny. At center, King Midas, with his donkey ears, rides on horseback, carrying a branch. The powerful ruler had been granted his wish of turning everything he touched into gold, which ultimately led to his demise. In the background are King Croesus, famed for his fortune, and Polymestor, the ancient Greek ruler who killed King Priam’s son in order to steal his treasure. On horseback at right is Pygmalion, whose digging symbolizes the search for earthly treasures.

Strewn on the ground are the bodies of three victims who died because of their gluttony. The cartouche at top bears a Latin inscription reminding the viewer, “As Tantalus is ever thirsty in the midst of water, so is the miser always desirous of riches.”

Stop 37. Stavelot Triptych

Triptych containing two small Byzantine triptychs on the center panel. Meuse River Valley.

Ca. 1156–58

Wood panels with copper-gilt frames, silver pearls and columns, gilt-brass capitals and bases, vernis brun domes, semi-precious stones, intaglio gems, beads, champlevé and cloisonné enamels

19 inches (484 mm) x 26 inches (660 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Joshua O’Driscoll, Associate Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

According to legend, the True Cross, on which Christ was crucified, was discovered in Jerusalem by St. Helena (ca. 255–330), mother of Constantine the Great (ca. 272–337), the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. Helena brought the cross to Constantinople, where for centuries it served as the source for precious gifts from the Byzantine emperors. Abbot Wibald of Stavelot (d. 1158), in modern-day Belgium, commissioned this triptych. Wibald traveled to Constantinople in 1155 to 1156 to negotiate a marriage for Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, and the two small triptychs on the center panel were likely gifts acquired on that diplomatic mission.

The lower reliquary features splinters of wood arranged to form a cross. The upper reliquary contained a pouch with a fragment of the Virgin Mary’s garment and dirt from the Holy Sepulcher in a cavity. These relics are now preserved separately.

The wings of Wibald’s triptych feature enameled scenes of exceptional quality depicting the Legend of the True Cross. The story begins at bottom left, with Constantine having a vision of the cross in his sleep. Above, he defeats his rival Maxentius, using the cross as his battle standard. Constantine then accepts Christianity and is baptized by Pope Silvester. The three roundels on the right side tell the story of Empress Helena and her discovery of the True Cross. From the bottom, they show Helena interrogating the Jews, discovering three crosses, and then identifying the True Cross through the miraculous resurrection of a dead youth. Implicit in these roundels is the idea that Jews were responsible for Christ's crucifixion, a link which has had a devastating effect on Jewish communities for centuries.

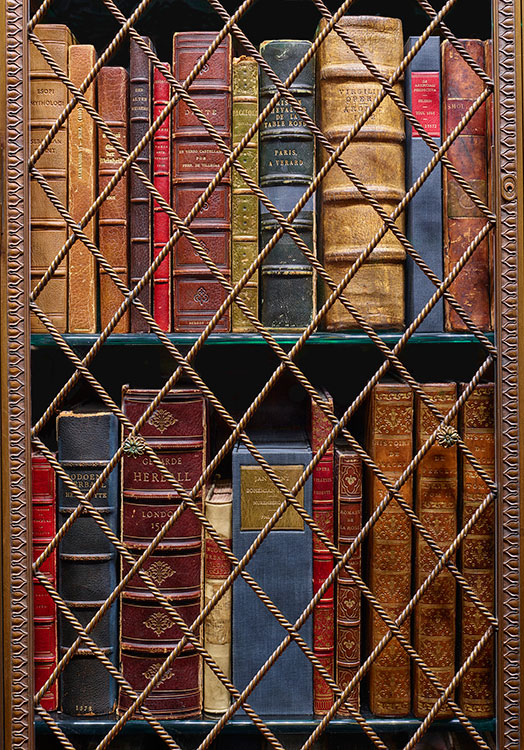

Stop 38: On the Shelves

Jesse Erickson, Astor Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

While this room was designed with one tier of bookshelves, the scale of Morgan’s collections necessitated blocking up windows and the addition of two further tiers. The shelves along these walls contain just part of the Morgan’s vast collection of rare printed books. The collection ranges from the earliest examples of printing, called incunables, made in the fifteenth century, to first editions by authors living today.

Much of what you see was originally collected by Pierpont Morgan himself. While he did acquire large caches and whole libraries, Morgan was primarily looking for books that had something special to offer: distinguished provenance, an author’s annotations, or a rare binding, features that would make a printed book, which was produced in multiples, a unique object.

The collection has grown and developed since Morgan's original acquisitions. In the bookcases to either side of the fireplace are more-recently donated collections, including, on the left, the Elisabeth Ball Collection of Early Children's Books, and, on the right, the Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection of literary and scientific volumes.

Stop 39. The Role of Conservation

Maria Fredericks, Sherman Fairchild Head of the Thaw Conservation Center

Most of the objects in the Morgan’s collection are on paper or parchment, some with delicate pigments or dyes that can change or fade with too much exposure to light. Because of this inherent fragility, most of our treasures can only be displayed for a few months at a time, under controlled lighting conditions. Frequently rotating our installations helps preserve our collections and also allows us to highlight the vast range of our holdings.

To preserve our collections for future generations, we have a team of conservators and preparators who specialize in paper, parchment, and book bindings. Located in the Morgan’s Thaw Conservation Center, they are responsible for making sure collection objects are safely housed and displayed. We also evaluate and treat objects that have deteriorated or have been damaged. We monitor the temperature, humidity, and light levels in our galleries and vault spaces, to ensure that conditions are optimal for preservation. With over half a million items under our care, and more than one thousand works shown in our galleries each year, the Morgan’s conservation staff plays a critical role in preserving and presenting the museum’s collections.

Stop 40. The Gutenberg Bible

Biblia Latina

Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg & Johannes Fust

Ca. 1455

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1896.

John McQuillen, Associate Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

The technology of printing texts and images had long been practiced in Asia, but by around the year 1400, Europe had only the technology to print images. The European development of printing texts with movable type was introduced in the early 1450s by Johannes Gutenberg, his assistant Peter Schoeffer, and Johannes Fust in Mainz, Germany. This large Latin Bible, referred to as the Gutenberg Bible, is the first substantial work produced on a printing press in the West. Prior to Gutenberg, it could take a scribe nearly a year to write out one copy of the Bible by hand. However, with the advent of the printing press, several hundred copies of a book could be produced within a few weeks or months, which significantly impacted the spread of information and development of literacy.

Gutenberg printed 180 copies of the Bible, some on paper and some on the more expensive animal skin, known as vellum or parchment; only forty-eight copies still exist today, and three are at the Morgan. Pierpont Morgan acquired his first copy in 1896 from the London bookseller Henry Sotheran. This copy is printed on vellum and adorned with hand-painted decoration produced in Bruges, Belgium, around 1460, but with heavy nineteenth-century restorations. Four years later, Morgan obtained a second copy through the purchase of the library of Theodore Irwin. The Irwin copy is printed on paper and was decorated by a local artist in Mainz, but it comprises only the Old Testament.

Finally, in 1911, Morgan was able to acquire at auction a complete paper copy in pristine condition. The red and blue painted initials indicate that this copy was originally owned by the monastery of Kirschgarten near Worms, Germany, just south of Mainz along the Rhine river. In honor of the importance of this pivotal invention to the history of the book in western culture, one of the Morgan’s volumes is always on display.

Stop 41: Librarian’s Work

Philip Palmer, Robert H. Taylor Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts

While the East Room is the showpiece of the building, it is also very much a working library, with a number of conveniences designed to enable the daily tasks of librarians. During the planning stage, Morgan’s nephew Junius explored the use of specially designed hinges that would allow the doors on the bookcases to open fully, maximizing shelf space and allowing for easy retrieval of books. The cases also come with a lock to secure their contents. While the two upper tiers were designed with brass railings, concern for the safety of librarians pulling volumes from the lower shelves led to the addition of bronze guard rails. A book elevator was installed in one of the concealed spaces to allow safe transportation of heavy tomes to and from the upper tiers.

Belle Greene’s office also contained several innovations to make her work efficient. She had custom-built card-catalog cases to facilitate her work documenting and organizing the collection, and a chair that could swivel, allowing her to manage several tasks at once. A custom-designed telephone table also fostered ease of communication with Morgan and with a wider circle of colleagues and dealers.

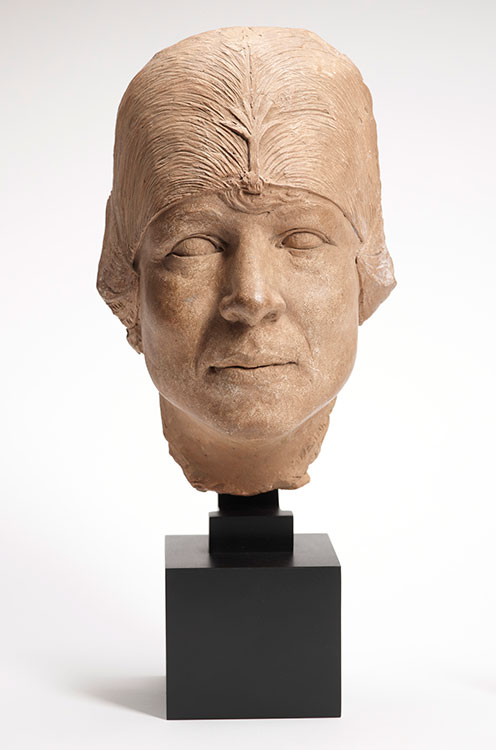

Stop 42. Bust of Belle Greene

Jo Davidson (American, 1883–1952)

1925

Terra cotta

11 x 7 x 5 3/4 inches (27.9 x 17.8 x 14.6 cm)

Purchased on the Charles Ryskamp Fund, 2018

Rachel Federman, Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Drawings

A sculptor well known for his portraits, Jo Davidson made numerous busts of writers, artists, and political and military figures during the first half of the twentieth century. This terra-cotta bust of Belle da Costa Greene was recently rediscovered in Davidson’s estate and acquired by the Morgan in 2018. Like many of Davidson's portraits, it was probably not a commission but, rather, one of the busts he made when he encountered someone whose face he found interesting. Davidson may have met Belle Greene through publisher and bibliophile Mitchell Kennerley, who was a close friend of them both, especially in the mid-1920s, when this bust was made. This is the only known sculpted portrait of the first Director of the Morgan and one of the few surviving life portraits of her in any medium.

Stop 43. St. Elizabeth Holding a Book

St. Elizabeth Holding a Book

Germany, Ulm (Swabia)

Early sixteenth century

Lindenwood, with polychromed and gilt decoration

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan in 1911

An inscription on the gown of this elegantly carved figure identifies her as St. Elizabeth. The foundry mark of the Ulm cathedral architects is located on her hem and sleeve, suggesting the sculpture’s origin. She may represent St. Elizabeth of Schönau (1129–1165), a German nun who published three volumes describing her divine visions, instead of the more well-known thirteenth-century St. Elizabeth of Hungary (1207–1231), who is typically depicted holding roses or distributing alms. The statue was restored in the nineteenth century, and the hands and book may date to that period.