Stop 27. North Room, or the Librarian’s Office

Sidney Babcock, Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen Curator of Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets

In early 1906, as construction of his Library neared completion, Morgan hired a young librarian to oversee its day-to-day affairs. Her name was Belle da Costa Greene. Her office is the intimate, two-story space opposite the entrance, now known as the North Room. The ceiling paintings were created in the studio of James Wall Finn, who based three of the horizontal panels on Renaissance examples, with the fourth replicating a ceiling painting in the Doge’s Palace in Venice by the eighteenth-century Italian painter Giambattista Tiepolo.

The perimeter of the ceiling is decorated with painted stucco reliefs, including twelve portraits based on Italian Renaissance medallions depicting ten men and two women who were among the great patrons of their era. The fireplace mantel, with its parade of misbehaving children, was provided by the Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini.

From this room, Greene managed acquisitions, cataloged the collection, and corresponded with dealers and scholars, until her retirement in 1948. The room served as the Director’s office until the late 1980s. The space was closed to the public until the 2010 renovation of the library when it was reimagined as a gallery for the Morgan’s collection of antiquities. It now features ancient western Asian seals and tablets, Egyptian and Greco-Roman sculpture, and early medieval ornaments from the Thaw Collection.

Stop 28. Belle Greene, Librarian

Baron Adolf de Meyer (1868–1946)

1912

Photograph

Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Erica Cialella, 2020–2022 Belle da Costa Greene Fellow

Born in 1879, Belle da Costa Greene was named Belle Marion Greener at birth. She grew up in a predominantly African American community in Washington, DC. Her father, Richard T. Greener, was the first Black graduate of Harvard College and a prominent educator and racial justice activist. After Belle’s parents separated, her mother, Genevieve Ida Fleet Greener, changed her surname and that of the children to Greene. While Belle was still in her teens, Genevieve and the children added “da Costa” to their surname and passed as a white family of Portuguese descent.

Greene and Junius S. Morgan II, Morgan’s nephew and advisor on Library matters, met at the Princeton University Library, where Junius was a librarian and Greene likely was a cataloger. In 1905, Junius enlisted Greene to prepare Morgan’s books for transport to the Library. On Junius’s recommendation, Morgan hired Greene to manage his “bookman’s paradise.”

Greene served as a de facto site manager while construction was in its final stages. She went on to run the Library for the rest of her working life, ultimately serving as the first Director of what is now the Morgan Library & Museum and remaking a private treasury into a center for scholarly inquiry and public engagement.

Stop 29. Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets

Sidney Babcock, Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen Curator of Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets

Pierpont Morgan’s collecting interests were broad, and the North Room display highlights his particular interest in cylinder seals from ancient western Asia. These are from the civilizations of

Mesopotamia, now modern-day Iraq. The earliest examples are more than five thousand years old.

Ancient Mesopotamian seals are among the first known objects to use pictorial symbols to communicate ideas. Many of the images represent human qualities and other concepts in the religious and poetic literature of ancient western Asia, including the Judeo-Christian Old Testament. Seals were engraved with scenes that appear in relief when rolled over clay. The impressed clay dried and hardened into a seal for doors, jars, boxes, and baskets. Their principal function in later times was to impress clay tablets on which records were inscribed in order to authenticate a document. Worn by their owners, seals offered protection and brought good luck.

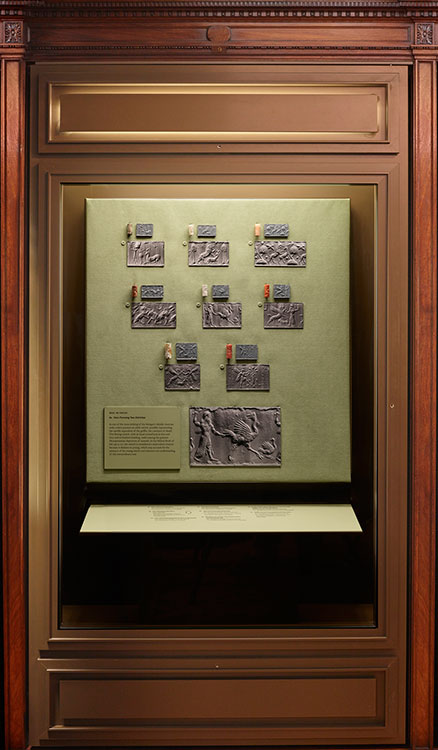

A selection of seals from the Morgan’s collection are shown with modern impressions replacing the clay used in antiquity. Below each impression is a photographic enlargement that clarifies the detail and beauty of the carving. Despite being among the smallest objects produced by sculptors, seals feature imagery that enables us today to enter the visual world of the ancients.

Stop 30. Earliest Account of the Deluge

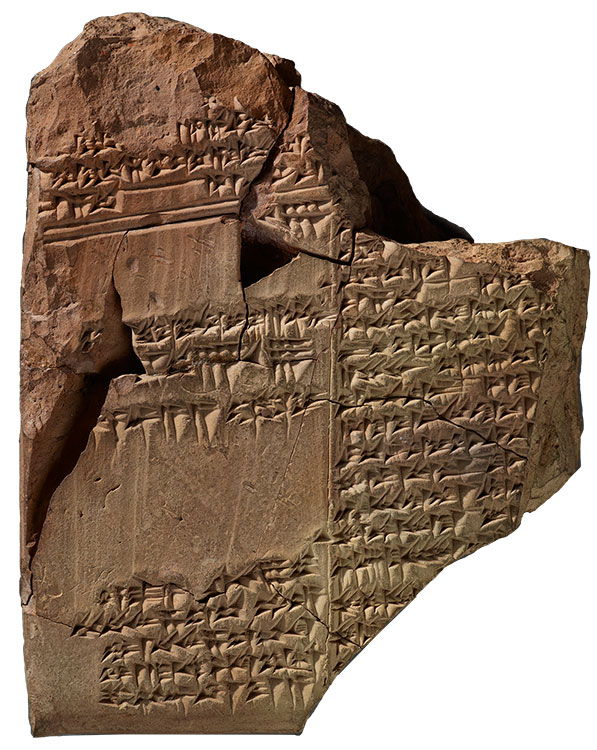

Mesopotamia, First Dynasty of Babylon, reign of King Ammi-saduqa (ca. 1646–1626 BC)

Clay

114 x 90 mm

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan between 1898 and 1908.

Sidney Babcock, Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen Curator of Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets

The earliest known writing system was developed in southern Mesopotamia sometime during the middle of the fourth millennium B.C., when a system to keep track of the distribution of resources, such as produce and livestock, became an economic necessity. Using what they had at hand, the Mesopotamians took reeds from the riverbanks and adapted them as tools to impress into clay wedge-shaped marks that were then assigned meanings. This was an intellectual achievement that amounted to nothing less than the invention of writing. Cuneiform, from the Latin word cuneus, meaning “wedge,” evolved into a full-fledged, syllable-based writing system that was used for over three thousand years.

This precious fragment of a tablet is the earliest known version in the Akkadian language of the story of the Great Flood, familiar to many from the Christian Bible. The epic begins when the gods create man, though they soon tire of him and decide to destroy all of mankind. The god Enki (Ea) tells the mortal Atrahasis of the impending flood and instructs him to build an ark. With over 1200 lines, the story filled three tablets. The Morgan fragment, from the second tablet, preserves a unique statement with the work’s title—“When Gods Were Men”—as well as the name of the scribe and the place and date on which he copied it.

Translated into modern English, one passage reads:

The Flood roared like a bull,

Like a wild ass screaming the winds

The darkness was total, there was no sun…

For seven days and seven nights

The torrent, storm, and flood came on…

Stop 31. Bust of Giovanni Boccaccio

After Giovanni Francesco Rustici (Italian, 1475–1574)

Late 16th or 17th century

Bronze, mounted to marble

15 x 16 1/2 x 7 inches (381 x 419 x 178 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

Above the mantel in the North Room is a bronze bust of a smiling man in clerical garb, mounted on a white marble surround, and placed between two porphyry urns. While this bust has occupied an esteemed place in Belle Greene’s office since 1910, only in recent years has the sitter’s true identity been determined.

Morgan acquired the bust in 1909 and it was long thought to depict the Italian Renaissance poet Francesco Petrarca, or Petrarch. Yet the round face and jovial, smiling mouth struck curators as a curious way to depict the serene Petrarch. Research revealed that the bust is actually a bronze cast after a marble bust from the tomb of the Florentine poet Giovanni Boccaccio. The original bust was made by the Renaissance sculptor Giovanni Francesco Rustici in 1503. The Morgan’s bronze was likely cast when the tomb was moved, probably in the seventeenth century.

The work fits the description of Boccaccio by his contemporary Filippo Villani: “Tall and rather stout of build, Boccaccio had a round face with the nose slightly flat above the nostrils; rather large, but nonetheless attractive and well-defined lips; and a dimpled chin that was charming when he laughed.”

Stop 32. Running Eros, Holding a Torch

2nd or 1st century BC [200–0 BC?]

Bronze

23 3/16 inches (589 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1902

Joshua O’Driscoll, Associate Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

Morgan collected a vast number of antiquities, some from excavations that he sponsored. Most of these objects are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he served as president, or at the Wadsworth Atheneum, in his native Hartford, to which they were presented by his son, Jack, following Morgan’s death. During his lifetime, however, Morgan chose a select few antiquities to keep with him in his library.

Among his favorite objects was this bronze figure. This depiction of Eros as a winged child bearing a torch was excavated from the ruins of a cluster of Roman villas located in Boscoreale, a town buried in the same Mount Vesuvius eruption that destroyed nearby Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 AD. The theme of love and desire, personified by Eros, was a favorite decorative motif for garden statuary appropriate to the informal atmosphere of these ancient resort towns where many wealthy Romans had villas.