Stop 17. J. Pierpont Morgan’s Study

The West Room is the personal study of Pierpont Morgan. Like many members of his social class, he collected art for himself and on behalf of the museums he supported. When his collection of rare books and manuscripts grew beyond the space available to store it, he commissioned this library containing a spacious and richly appointed study. In this private space far uptown from his Wall Street office and adjacent to his home he could meet with business colleagues, art dealers, and museum directors. During the last years of his life, he strove to build his collection working with his librarian, Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950), who would later become the first Director of the Morgan. This room, with its display of mostly Renaissance works of art, reflects the Italianate aesthetic of the building, and Morgan’s own fondness for beautifully crafted objects.

Stop 18. Anna Willemzoon with St. Anne; Willem de Winter with St. William of Maleval

Hans Memling (Flemish, ca. 1440–1494)

1467–70

Oil on panel

32 7/8 x 10 5/8 inches (835 x 270 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907.

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator of Drawings and Prints

Hans Memling was the leading painter in Bruges during the second half of the fifteenth century, when the city was one of the primary banking and trade centers in Europe. Memling painted both portraits of the merchant class and religious scenes–and also works like these panels, which combine portraits and sacred subjects. The two paintings once formed the inner wings of an altarpiece commissioned by Jan Crabbe, the abbot of a local monastery. They include depictions of Crabbe’s relatives, along with their patron saints. At left, St. Anne stands behind an older, kneeling woman. This is Crabbe's mother, Anna Willemzoon. At right, St. William of Maleval appears in armor behind a young man, the abbot's younger half-brother Willem de Winter, who wears clerical garb over his knightly armor. The central panel of the triptych, a Crucifixion, is preserved in Vicenza, while the two exterior wing panels are in Bruges.

Stop 19. Portrait of an Ambassador

Domenico Tintoretto (Italian, 1560–1635) and his workshop

Ca. 1600

Oil on canvas

50 x 40 inches (1270 x 1016 mm)

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1929

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator of Drawings and Prints

The unidentified sitter in this portrait, painted in Venice in the workshop of Domenico Tintoretto, son of the more famous Jacopo, is believed to have been a North African ambassador to Venice. The sitter is dressed in European costume, although the white sash around his waist is not typical of Venetian dress. The rectangular package on the table next to him, likely a bundle of letters secured by a wax seal, may indicate his role as a diplomat or an envoy. According to contemporary sources, Domenico's studio was often visited by diplomats who wished to commission portraits.

The painting was purchased by Morgan’s son, Jack, in 1929 and is one of the few paintings he acquired that remain at the Morgan. In an effort to reduce his estate, and the inheritance taxes that would accompany it, Jack Morgan sold many of the paintings he inherited from his father in the 1930s and early 1940s, before his death in 1943.

Stop 20. A Passion for English Literature

Sal Robinson, Lucy Ricciardi Assistant Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts

Morgan filled the single row of book cases lining his personal study with great works of English literature. He made significant acquisitions of both books and literary manuscripts by Frances Burney, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and the Brontë sisters in the early twentieth century. Some rare editions of novels by these authors can be seen in Cabinet 17, to the right of the window. Among his early purchases of works by British women authors was the handwritten manuscript for Les Dames vertes by French novelist Amantine Dupin, who wrote under the pen name George Sand, which he bought in 1896. To care for the historic bindings in the collection, Belle Greene hired binder Marguerite Duprez Lahey in 1908.

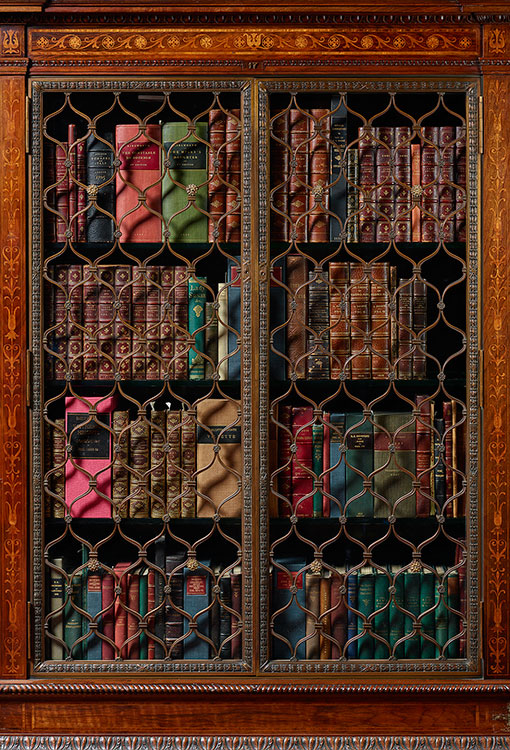

Stop 21. Secret Shelves

Sheelagh Bevan, Andrew W. Mellon Associate Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

At the time of the building's construction, it was common to design discreet spaces for book collectors to store volumes of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literature featuring erotic engravings. A secret set of shelves, which may have served that purpose, was discovered by library staff in Morgan's private study. When the bookshelves immediately to the left of the fireplace are pushed back, the case in the adjacent cabinet can slide to the right, allowing a hidden set of shelves at the back of the central cabinet to come into view. At the time of their discovery, the shelves were empty. Speculation persists that Morgan concealed his collection of erotica in this space—classic works, such as Fanny Hill, La nouvelle Sapho, and Le diable au corps. Two years after Morgan's death, his son, Jack, sold these and other titles to a dealer in Paris.

Stop 22. The Vault

Sheelagh Bevan, Andrew W. Mellon Associate Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

With his valuable collection in a gleaming new building, Morgan made sure to implement security measures. In addition to the precautions against intruders, which included a burglar alarm system, a watchman, and the neighborhood’s mounted policemen, Morgan had internal protections, including locked cabinets in his study and a steel-lined vault. This secure chamber was designed for Morgan to house works of particular value. Its walls are lined with solid steel, and the heavy door is secured by a combination lock. For many years, Morgan’s medieval and Renaissance manuscript collection was stored here. The shelves now contain a selection of rare books from the collection of the bibliophile and bookbinder Julia P. Wightman, finely tooled cases once used to house manuscripts, and art objects. Above the grating is a collection of first editions, proofs, and annotated copies by more modern writers—authors such as Julian Barnes, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, Salman Rushdie, and Hilary Mantel.

Stop 23. The Panic of 1907

Colin B. Bailey, Director

Morgan and his staff were given the keys to the building in late 1906. By the start of 1907, Morgan spent the majority of his time in his new Library, having largely retired from Wall Street. But his days as a powerful banker were not over, and his Library would be the setting for one of the most important acts by a private individual during a time of national crisis. In the middle of October 1907, the stock market plummeted, and a financial panic strangled the nation—people were withdrawing their funds en masse, and banks were declaring bankruptcy. By Sunday, November 3, after two weeks of crisis, the unregulated trust companies were still struggling to stay in business. Morgan summoned the trust company presidents to his library and quietly locked the front doors. He was determined to resolve the crisis that evening. Since the United States had no central bank, Pierpont Morgan and his colleagues needed to raise millions of dollars in loans from solvent banks and wealthy industrialists to try to stabilize the economy. Just after four in the morning, Morgan announced they would all sign a pledge, with each committing a certain sum for the final-stage bailout. At the time, mounting concerns about one man’s inordinate power were eclipsed by an outpouring of acclaim. The panic led to the founding of the Federal Reserve System in 1913.

Stop 24. Virgin and Child with Cherubim

Antonio Rossellino (Italian, 1427/28-1479)

1450s

Marble

31 1/2 x 22 1/8 inches (800 x 562 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1913.

This exceptionally fine relief was executed by Antonio Rossellino, one of the most talented sculptors active in Florence in the 1460s and 1470s. For this depiction of the Virgin and child, he employed a technique known as rilievo schiacciato, or flattened relief. The composition suggests that he looked at paintings in perspective as well as three-dimensional sculpture in creating a play of light and shadow in the low, carved surface of the marble. Damage along the perimeter of the stone suggests that it was removed from a tabernacle before being framed. The relief has enjoyed tremendous popularity since its creation and gave rise to many plaster casts and replicas.

Stop 25. Portrait of Pierpont Morgan

Frank Holl (British, 1845–1888)

1888

Oil on canvas

49 3/16 x 39 5/16 inches (1248 x 997 mm)

Gift of J.P. Morgan II, 1967

Joel Smith, Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography

Already one of the world’s most prominent bankers, Pierpont Morgan was fifty-one years old when he commissioned this portrait of himself in 1888. At that time, he lived with his wife, Frances Tracy Morgan, and their four children in a brownstone adjacent to this building.

In depicting his sitter, the British painter Frank Holl downplayed Morgan’s skin condition, called rhinophyma, which would increasingly redden and inflame his nose. The banker was so fond of the portrait that he gave photographs of it to his friends.

Morgan hung this portrait in the library of his house, behind the couch where he napped, and not in his study. Instead, his desk faced a portrait of his father, Junius Spencer Morgan, above the mantel. Holl’s portrait of Morgan was passed down through the family and given to the museum in 1967 by Pierpont Morgan’s grandson J.P. Morgan II (1918–2004).

Stop 26. Virgin and Saints Adoring the Christ Child

Pietro Perugino (Italian, ca. 1450–1523)

Ca. 1500

Tempera on panel

34 1/2 x 28 3/8 inches (876 x 721 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator of Drawings and Prints

Known for his graceful figures, Perugino was the leading painter from Umbria, a region in central Italy, during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Using harmonious jewel-like tones, the artist depicted the Virgin flanked by St. John the Evangelist and an unidentified female saint, perhaps Mary Magdalene. The inscription on the frame, referring to the Christ Child, is from Psalm 45: Fairer in beauty are you than the children of men; grace is poured out upon thy lips; thus God has blessed you forever. The elegant figures and delicate landscape are hallmarks of Perugino’s graceful style, which had a lasting impact on his most famous pupil, Raphael.

When Morgan was furnishing his study he pursued Italian paintings in earnest, working with many art dealers. This panel was procured for Morgan in 1911 by the British agent and critic Robert Langton Douglas from the Sitwell family, whose members are noted for their eccentric collections, many of which were housed at Renishaw Hall in Derbyshire, England.