Stop 1. History and Architecture

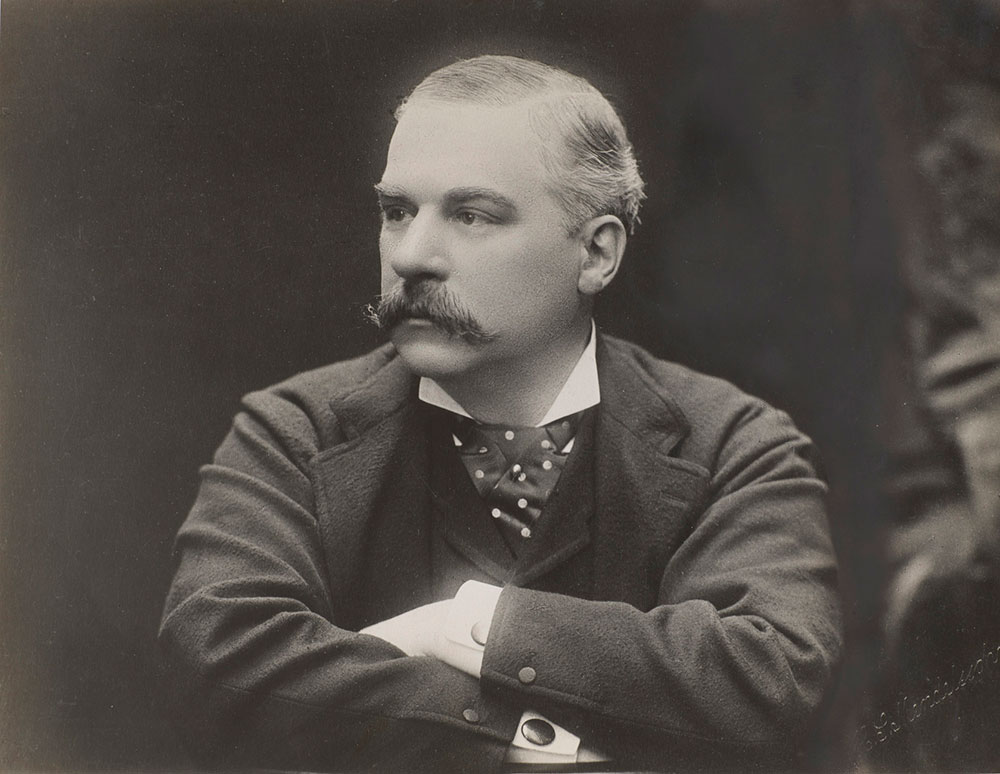

A museum and independent research library, the Morgan Library & Museum began as the personal library of financier, collector, and cultural benefactor John Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913). As early as 1890, Morgan had begun to assemble a collection of illuminated, literary, and historical manuscripts, early printed books, and old master drawings and prints.

Mr. Morgan's Library, as it was known in his lifetime, was built between 1902 and 1906 adjacent to his New York residence at Madison Avenue and 36th Street. In 1924, eleven years after Pierpont Morgan's death, his son J. P. Morgan, Jr. (1867–1943), known as Jack, realized that the library had become too important to remain in private hands. He fulfilled his father's dream of making the library and its treasures available to scholars and the public alike by transforming it into a public institution. The Morgan opened its doors in October 1928.

Hello. I’m Colin B. Bailey, Director of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Here you can learn about the history of American financier J. Pierpont Morgan’s library and his collection of rare books, manuscripts, drawings, and prints. Pierpont Morgan began collecting these remarkable objects more than a hundred years ago—and our collections continue to grow. They include handwritten works by Beethoven, the Brontes, and Bob Dylan; manuscripts from the Middle Ages to Mark Twain and Virginia Woolf; drawings from Michelangelo and Rembrandt to Helen Frankenthaler and Martin Puryear; and rare printed volumes from the Gutenberg Bible to James Baldwin.

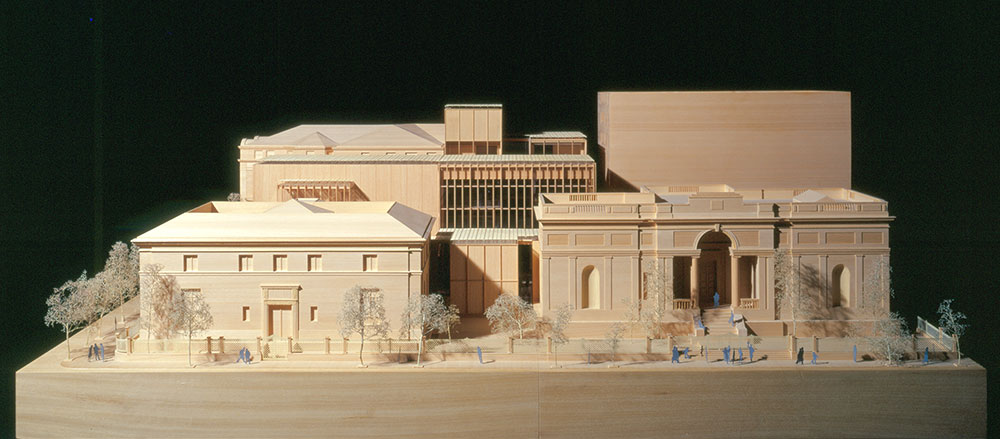

You’ll also learn about the sumptuous Renaissance-inspired library he built to house his expanding collection. The Morgan Library & Museum campus has grown to encompass Pierpont Morgan’s 1906 Library designed by Charles Follen McKim, a 1928 Annex by Benjamin Wistar Morris, a 2006 modernist glass and steel expansion by the Italian architect Renzo Piano, and a 2022 garden by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan that enriches the museum’s presence along 36th street.

Through its collections and programs, the Morgan Library & Museum celebrates creativity and the imagination, with the conviction that meaningful engagement with art, literature, music, and history enriches lives, opens minds, and deepens understanding. I hope you will enjoy learning more about the Morgan while visiting our campus or from home. Thank you for joining us.

Stop 2. Introducing J. Pierpont Morgan

Philip Palmer, Robert H. Taylor Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts

In 1837, John Pierpont Morgan was born into a wealthy and distinguished family in Hartford, Connecticut. As a young man, he traveled to continue his education in Europe, where he fostered a passion for history, art, and literature before beginning his banking career in New York in 1857.

In 1861, Morgan married Amelia Sturges, known as Memie. She was the daughter of the prominent arts patron Jonathan Sturges. Memie had tuberculosis, a slowly progressing disease that was one of the leading causes of death at the time. She died on their honeymoon four months later. Morgan would marry a second time, to Frances Tracy in 1865. Together they would raise four children: Louisa, Jack, Juliet, and Anne.

Pierpont Morgan worked closely with his father’s London-based bank, importing capital to fund the emerging US economy. He played an important role in the volatile railroad industry in the years after the Civil War. When Morgan’s father, Junius, died in 1890, he turned his attention to industrial corporations which would form the infrastructure that propelled America’s expansion. He organized General Electric, US Steel, International Harvester, and AT&T, the modern form of American Telegraph and Telegram.

On a 1913 trip through Egypt he became unwell and returned to Rome where he died on March 31. His body was returned to New York and laid out in his library. Morgan’s funeral was held on April 14 on 16th Street, near Second Avenue, at St. George’s Church, where he had been a deacon. The procession traveled to Hartford, Connecticut, where Morgan was interred in the family plot at Cedar Hill Cemetery.

Stop 3. The 1906 Library and the 1928 Annex

Colin B. Bailey, Director

In 1880, Pierpont Morgan and his wife Frances Tracy Morgan, known as Fanny, and their children moved to a brownstone at the corner of 36th Street and Madison Avenue. By 1900, Morgan was focused primarily on his collections, which were growing rapidly and needed a new home. He commissioned a private library adjacent to his house in 1902. It was designed by the renowned architect Charles Follen McKim, of the firm McKim, Mead & White.

Following Pierpont’s death in 1913, Fanny Morgan continued to live in the brownstone until her own death in 1924. That same year, their son, Jack, decided to transform Morgan’s Library into a public institution in order to fulfill his father’s wish that his collection be used for the “instruction and pleasure of the American people.” The brownstone was replaced by a second marble structure, called the Annex, designed by Benjamin Wistar Morris and completed in 1928, when the Morgan officially opened its doors.

From 1959 to 1962, the architect–and the founder’s great nephew–Alexander P. Morgan oversaw a modest expansion, adding office and gallery space, and a lecture room. In 1988, the Morgan added a third historic building to its campus—a mid-nineteenth century brownstone on the corner of 37th Street. This rare freestanding brownstone was once the home of Morgan’s son, Jack, his wife, Jane Norton Grew Morgan, and their family.

After nearly seventy-five years as a museum and research library, the Morgan had expanded its collections significantly. In 2001, Renzo Piano was hired to integrate the Morgan’s buildings into a seamless campus. He added the many structures in glass and off-white painted steel that join the historic buildings together.

Stop 4. The 2006 Expansion

Colin B. Bailey, Director

Between 2001 and 2006, Renzo Piano was hired to help integrate the institution’s various functions—and its three distinct historic buildings. Piano also added three new structures to balance the historic ones. These include the Clare Eddy Thaw Gallery, a space modeled on a Renaissance studiolo, or small room for quiet study. The Thaw Gallery is a perfect twenty-foot cube that holds changing exhibitions.

Piano also designed the glass building on the opposite side of the piazza. It houses museum offices.

The large pavilion at the center of the campus connects the old and new buildings and shifted the Morgan’s entrance to Madison Avenue. On the second floor is the Engelhard Gallery, a relatively large space for special exhibitions. The third floor is devoted to the Sherman Fairchild Reading Room, where researchers—including musicians, artists, and writers—can consult rare materials from the Morgan’s vaults. The central axis through this pavilion leads to the sky-lit piazza.

Stop 5. Land Acknowledgment

Christina Rollo / Alamy Stock Photo

Colin B. Bailey, Director

The history of this site began long before Pierpont Morgan purchased the property along Madison Avenue between 36th and 37th Streets.

The Morgan Library & Museum stands on land that is part of Lenapehoking, the unceded ancestral homeland of the Lenape people. At the Morgan, we acknowledge and pay respect to the original stewards of Lenapehoking, and we recognize the enduring significance of these lands and waterways for the Lenape Nations and the many Indigenous communities who live here today.

The Morgan also recognizes the violent history of settler colonialism and its ongoing impacts on Indigenous peoples and lands. Our staff is committed to confronting this legacy in our work at the Morgan, and to honoring Indigenous voices.

Stop 6. Gilbert Court

Colin B. Bailey, Director

In 2006, Renzo Piano created a ground-floor entrance along Madison Avenue. Visitors pass through the admissions area into a light-filled central piazza, surrounded by the Morgan’s historic buildings. The piazza is called the Gilbert Court, after S. Parker Gilbert, a past President of the Morgan’s Board of Trustees who championed the expansion of the museum’s campus.

From the court, visitors can choose to take a break in the café or to explore the historic Library, the Annex exhibition galleries, the modern Thaw and Engelhard Galleries, or the Morgan Shop in the brownstone.

Stop 8. Wall Drawing 552D

Sol LeWitt (American, 1928-2007)

1987

Color ink wash

Gift of the LeWitt family in honor of Richard and Ronay Menschel; Installation made possible by the Charina Endowment Fund

Isabelle Dervaux, Acquavella Curator of Modern and Contemporary Drawings

In 2018, the family of artist Sol LeWitt donated to the Morgan Wall Drawing 552D. The gift included detailed instructions for the creation of the drawing, which was executed by a team from LeWitt’s studio.

LeWitt first became known in the mid-1960s for his modular sculptures based on the cube. In 1968, he made his first wall drawing by tracing lines directly on the wall according to a pre- established system. Over the next forty years, he conceived more than 1,200 wall drawings in pencil, colored ink, and acrylic. Although the wall may ultimately be painted over, each drawing exists as a set of instructions that can be re-created on another wall by another person.

In the early 1980s, inspired by the rich colors of Italian Renaissance frescoes, LeWitt began using colored ink wash applied with rags, mixing wiping and pounding techniques. He limited his palette to four colors—gray, yellow, red, and blue—which he layered and superimposed to produce variations. This wall drawing was first created in 1987. The artist described its motif as “not quite a cube.” The tilted form produces an illusion of volume while the black border that interrupts it preserves the sense of flatness of the wall.

See time-lapse video of installation

Stop 9. Morgan’s Art Collections

Bottle vase, the “Morgan Ruby”

China, Qing dynasty, Kangxi period (1662–1722)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907.

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

Pierpont Morgan’s taste encompassed global art. The Morgan family brownstone was filled with art objects from China, Japan, southeast Asia, and the Islamic world. These were displayed alongside objects from western Europe and America. Morgan also acquired significant collections of non-Western art for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he served as President from 1904 until 1913. He kept a few examples of Chinese vessels for his personal collection, including this bottle-shaped vase with its Langyao, or copper-red, glaze, known as the Morgan Ruby.

Stop 10. 1906 Library Building

Colin B. Bailey, Director

Situated on a residential block among its urban neighbors, J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library appears strikingly distinct yet surprisingly at home. Architect Charles Follen McKim drew on Italian Renaissance architectural precedents to design an American building that conveyed power and permanence, intimacy and grandeur. “Above all,” he told his client, “we are desirous that the design shall represent your views and reflect your judgment, in order that it may become a worthy monument to your munificence and public spirit.”

The building has remained the heart of the Morgan Library & Museum. The interior was renovated in 2010: the marble was cleaned, the displays were reimagined to allow visitors to engage more fully with the spaces and their history, and new, technologically advanced lighting was installed. In 2020–2022, the exterior of the building was restored: the roof was replaced, the foundation waterproofed and the marble and ironwork cleaned and restored. At the same time,the surrounding landscape and lighting were reimagined. These campaigns have restored the building to its original splendor, encouraging visitors to learn more about the creation and history of the Library.

Stop 11. The Builders

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

While we often speak of the building that Morgan and McKim made, it is more accurate to say there were hundreds of people, their names largely unknown to us today, who built this “bookman’s paradise.”

Charles Follen McKim, the lead architect and creative force behind the building, relied on a team of proficient draftsmen in McKim, Mead & White’s studio to create the design drawings that articulated his vision. He engaged Charles T. Wills as general contractor and a host of specialists to build and ornament the Library. Just after construction began in 1903, a series of strikes brought the entire New York building industry to a standstill in April. Progress on the Library was delayed as workers sought improved conditions and better pay. Construction resumed in November and work was completed three years later, thanks to the efforts of the teams of artisans and contractors, many from workshops headed by immigrants, who contributed their labor and creativity to the project.

Stop 12. The Decorators

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

Morgan purchased or commissioned the works in his study and library; however, they were created or sourced by a wide range of craftsmen and dealers. The London firm Cowtan & Sons designed the furniture based on Renaissance examples in the Victoria and Albert Museum, near Morgan’s London home. The British chaplain and art-dealer Robert Langton Douglas searched for Italian paintings for Morgan’s Renaissance villa, while Morgan’s trusted Paris dealer Jacques Seligmann offered the banker the finest objects and bronzes in his inventory.

Not everything, however, was as rare and expensive as it might seem. The dealer Stefano Bardini had fragments of an earlier wood ceiling, but the one you see in the room was largely executed by craftsmen in 1905 based on the historic model. The contemporary artist James Wall Finn gave the ceiling a coat of paint, which was artificially aged to create the appearance of an old ceiling. Likewise, the great fireplace mantel contains a small lintel that was sold as a fifteenth-century object by Bardini but was likely a modern creation. It is embedded in a stone and concrete surround created in 1905. Ultimately, Morgan was practical in his expenditures and creating this Italianate interior was the work of decorators as much as the great collector.

Stop 13: The Rotunda

The Rotunda served as the entrance to the Library during Morgan’s lifetime. For the visitor who entered from the street, the austere monochromatic façade would suddenly yield to a soaring, well-lit space, sumptuous in its profusion of colored stones and jewel-toned paintings.

Vertical panels of mosaic tiles adorn the walls, alternating with marble pilasters. Free-standing marble columns are topped with alabaster bowls. And rich blue columns clad in tiles of lapis lazuli flank the small door, over which is mounted a blue-and-white glazed Renaissance relief. The central oculus illuminates the surrounding painted dome and the relief panels in the blue and white stuccoed apse, as well as three painted lunettes.

Stop 14: The Rotunda: Lunettes

Roger Wieck, Melvin R. Seiden Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

The space is distinguished by three lunettes, or semi-circular paintings, above the entrance and the doorways to Morgan’s library and study. The paintings were executed by Harry Siddons Mowbray and they celebrate the history of western European literature from three different eras.

Above the entrance to the library, the ancient world is represented by Orpheus and Homer and scenes from the Iliad and the Odyssey. The lunette above the front doors is dedicated to the medieval world, symbolized by chivalric romances, with depictions of King Arthur, Lancelot, and Guinevere, as well as Dante with his beloved Beatrice and guide Virgil. Above the entrance to Morgan’s study, the scene pays homage to the Renaissance, featuring the muse of lyric and amorous poetry and characters from the Italian poet Torquato Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered, as well as Petrarch, whose sonnets honored his platonic love for Laura.

Mowbray painted these canvases in his studio and brought them to the library for installation. If you look closely, you will see that the gilded details are actually three-dimensional: Mowbray used a composite material to build these up so they would catch the light from the oculus. This was a technique used by the Renaissance painter Bernardino Pinturicchio, on whose sixteenth-century murals Mowbray’s were based. Mowbray also added a fictive, or trompe l'oeil, arch framing the painting above the entrance to match the real arches framing the other two lunettes.

Stop 15. The Rotunda: Dome and Apse

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator of Drawings and Prints

The Rotunda is capped by a domed ceiling with a central oculus. The dome is adorned with paintings, some simulating marble reliefs or mosaics. This decoration was undertaken by Harry Siddons Mowbray, who also painted the lunettes in the Rotunda and the East Room. Around the central skylight are female personifications of Religion, Art, Science, and Philosophy. The overall layout of the dome is based on the ceiling in the Stanza della Segnatura of the Vatican Palace, painted by Raphael during the Italian Renaissance. The architect Charles Follen McKim studied that ceiling and adjusted a few details, such as the format of the paintings simulating reliefs, to work with the proportions of his dome. Mowbray also studied the same ceiling, and his paintings in the Morgan dome emulate the mellowed tones that characterized Raphael’s frescoes before their recent restoration.

In the semicircular apse, opposite the original entrance, are two rows of white stucco reliefs against a blue background. The vertical panels depict allegorical figures while the octagonal ones are devoted to Roman deities. Although Mowbray made the ceiling paintings in his studio and later mounted them in this space, these reliefs were modeled on site, so that Mowbray could study the way they interacted with the ambient light.

See Raphael ceiling in the Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican

Stop 16. Virgin and Child with Two Kneeling Angels in a Lunette

Attributed to Luca della Robbia (Italian, ca. 1400-1482)

Ca. 1460

Glazed terracotta

54 x 40 1/4 inches (1372 x 1022 mm.)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910.

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator of Drawings and Prints

Morgan’s Library was filled with Renaissance flourishes. For example, above the small doorway that led to the Librarian’s Office is a glazed terracotta relief by the Renaissance sculptor Luca della Robbia. It features the Madonna and child in the center, with an adoring angel kneeling on either side. The figures are framed by a stone surround inscribed with the Latin phrase Soli Deo Honor et Gloria, which means “Glory and honor to God alone.” While the lunette seems perfectly suited to the doorway, Morgan only acquired it in 1910, several years after the building was completed. It was tailored to fit the available space.

As is typical of Luca della Robbia’s work, the figures appear in white against a deep blue background. Della Robbia developed a new type of glaze in the 15th century that made his ceramics especially durable, while allowing for a rich diversity of colors. This elegant relief originally graced the entrance to the Renaissance oratory of Santa Maria della Quercia in Florence and was sold by a descendant of the original patron to Morgan through the dealer Elia Volpi. Additional colorful, glazed reliefs by the Della Robbia workshop and their contemporaries can be found on the walls outside Morgan’s study.

Stop 17. J. Pierpont Morgan’s Study

The West Room is the personal study of Pierpont Morgan. Like many members of his social class, he collected art for himself and on behalf of the museums he supported. When his collection of rare books and manuscripts grew beyond the space available to store it, he commissioned this library containing a spacious and richly appointed study. In this private space far uptown from his Wall Street office and adjacent to his home he could meet with business colleagues, art dealers, and museum directors. During the last years of his life, he strove to build his collection working with his librarian, Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950), who would later become the first Director of the Morgan. This room, with its display of mostly Renaissance works of art, reflects the Italianate aesthetic of the building, and Morgan’s own fondness for beautifully crafted objects.

Stop 18. Anna Willemzoon with St. Anne; Willem de Winter with St. William of Maleval

Hans Memling (Flemish, ca. 1440–1494)

1467–70

Oil on panel

32 7/8 x 10 5/8 inches (835 x 270 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907.

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator of Drawings and Prints

Hans Memling was the leading painter in Bruges during the second half of the fifteenth century, when the city was one of the primary banking and trade centers in Europe. Memling painted both portraits of the merchant class and religious scenes–and also works like these panels, which combine portraits and sacred subjects. The two paintings once formed the inner wings of an altarpiece commissioned by Jan Crabbe, the abbot of a local monastery. They include depictions of Crabbe’s relatives, along with their patron saints. At left, St. Anne stands behind an older, kneeling woman. This is Crabbe's mother, Anna Willemzoon. At right, St. William of Maleval appears in armor behind a young man, the abbot's younger half-brother Willem de Winter, who wears clerical garb over his knightly armor. The central panel of the triptych, a Crucifixion, is preserved in Vicenza, while the two exterior wing panels are in Bruges.

Stop 19. Portrait of an Ambassador

Domenico Tintoretto (Italian, 1560–1635) and his workshop

Ca. 1600

Oil on canvas

50 x 40 inches (1270 x 1016 mm)

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1929

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator of Drawings and Prints

The unidentified sitter in this portrait, painted in Venice in the workshop of Domenico Tintoretto, son of the more famous Jacopo, is believed to have been a North African ambassador to Venice. The sitter is dressed in European costume, although the white sash around his waist is not typical of Venetian dress. The rectangular package on the table next to him, likely a bundle of letters secured by a wax seal, may indicate his role as a diplomat or an envoy. According to contemporary sources, Domenico's studio was often visited by diplomats who wished to commission portraits.

The painting was purchased by Morgan’s son, Jack, in 1929 and is one of the few paintings he acquired that remain at the Morgan. In an effort to reduce his estate, and the inheritance taxes that would accompany it, Jack Morgan sold many of the paintings he inherited from his father in the 1930s and early 1940s, before his death in 1943.

Stop 20. A Passion for English Literature

Sal Robinson, Lucy Ricciardi Assistant Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts

Morgan filled the single row of book cases lining his personal study with great works of English literature. He made significant acquisitions of both books and literary manuscripts by Frances Burney, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and the Brontë sisters in the early twentieth century. Some rare editions of novels by these authors can be seen in Cabinet 17, to the right of the window. Among his early purchases of works by British women authors was the handwritten manuscript for Les Dames vertes by French novelist Amantine Dupin, who wrote under the pen name George Sand, which he bought in 1896. To care for the historic bindings in the collection, Belle Greene hired binder Marguerite Duprez Lahey in 1908.

Stop 21. Secret Shelves

Sheelagh Bevan, Andrew W. Mellon Associate Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

At the time of the building's construction, it was common to design discreet spaces for book collectors to store volumes of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literature featuring erotic engravings. A secret set of shelves, which may have served that purpose, was discovered by library staff in Morgan's private study. When the bookshelves immediately to the left of the fireplace are pushed back, the case in the adjacent cabinet can slide to the right, allowing a hidden set of shelves at the back of the central cabinet to come into view. At the time of their discovery, the shelves were empty. Speculation persists that Morgan concealed his collection of erotica in this space—classic works, such as Fanny Hill, La nouvelle Sapho, and Le diable au corps. Two years after Morgan's death, his son, Jack, sold these and other titles to a dealer in Paris.

Stop 22. The Vault

Sheelagh Bevan, Andrew W. Mellon Associate Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

With his valuable collection in a gleaming new building, Morgan made sure to implement security measures. In addition to the precautions against intruders, which included a burglar alarm system, a watchman, and the neighborhood’s mounted policemen, Morgan had internal protections, including locked cabinets in his study and a steel-lined vault. This secure chamber was designed for Morgan to house works of particular value. Its walls are lined with solid steel, and the heavy door is secured by a combination lock. For many years, Morgan’s medieval and Renaissance manuscript collection was stored here. The shelves now contain a selection of rare books from the collection of the bibliophile and bookbinder Julia P. Wightman, finely tooled cases once used to house manuscripts, and art objects. Above the grating is a collection of first editions, proofs, and annotated copies by more modern writers—authors such as Julian Barnes, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, Salman Rushdie, and Hilary Mantel.

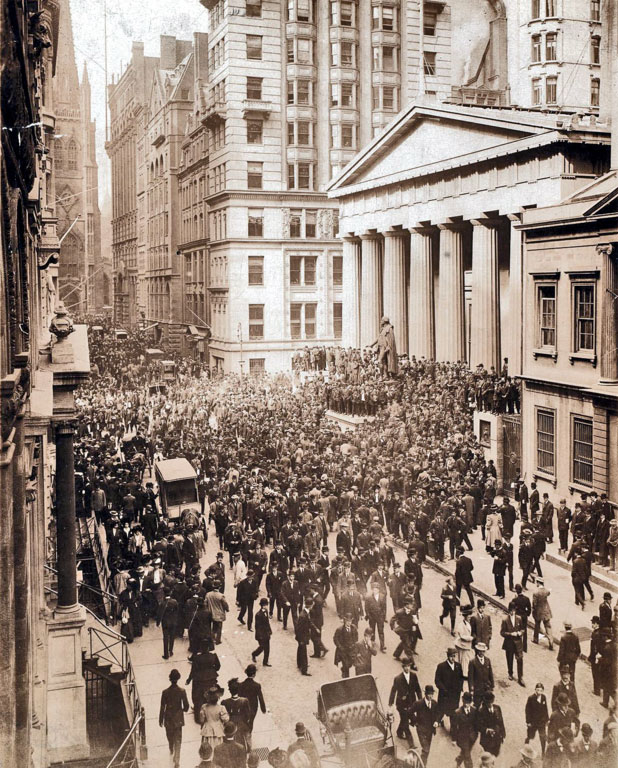

Stop 23. The Panic of 1907

Colin B. Bailey, Director

Morgan and his staff were given the keys to the building in late 1906. By the start of 1907, Morgan spent the majority of his time in his new Library, having largely retired from Wall Street. But his days as a powerful banker were not over, and his Library would be the setting for one of the most important acts by a private individual during a time of national crisis. In the middle of October 1907, the stock market plummeted, and a financial panic strangled the nation—people were withdrawing their funds en masse, and banks were declaring bankruptcy. By Sunday, November 3, after two weeks of crisis, the unregulated trust companies were still struggling to stay in business. Morgan summoned the trust company presidents to his library and quietly locked the front doors. He was determined to resolve the crisis that evening. Since the United States had no central bank, Pierpont Morgan and his colleagues needed to raise millions of dollars in loans from solvent banks and wealthy industrialists to try to stabilize the economy. Just after four in the morning, Morgan announced they would all sign a pledge, with each committing a certain sum for the final-stage bailout. At the time, mounting concerns about one man’s inordinate power were eclipsed by an outpouring of acclaim. The panic led to the founding of the Federal Reserve System in 1913.

Stop 24. Virgin and Child with Cherubim

Antonio Rossellino (Italian, 1427/28-1479)

1450s

Marble

31 1/2 x 22 1/8 inches (800 x 562 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1913.

This exceptionally fine relief was executed by Antonio Rossellino, one of the most talented sculptors active in Florence in the 1460s and 1470s. For this depiction of the Virgin and child, he employed a technique known as rilievo schiacciato, or flattened relief. The composition suggests that he looked at paintings in perspective as well as three-dimensional sculpture in creating a play of light and shadow in the low, carved surface of the marble. Damage along the perimeter of the stone suggests that it was removed from a tabernacle before being framed. The relief has enjoyed tremendous popularity since its creation and gave rise to many plaster casts and replicas.

Stop 25. Portrait of Pierpont Morgan

Frank Holl (British, 1845–1888)

1888

Oil on canvas

49 3/16 x 39 5/16 inches (1248 x 997 mm)

Gift of J.P. Morgan II, 1967

Joel Smith, Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography

Already one of the world’s most prominent bankers, Pierpont Morgan was fifty-one years old when he commissioned this portrait of himself in 1888. At that time, he lived with his wife, Frances Tracy Morgan, and their four children in a brownstone adjacent to this building.

In depicting his sitter, the British painter Frank Holl downplayed Morgan’s skin condition, called rhinophyma, which would increasingly redden and inflame his nose. The banker was so fond of the portrait that he gave photographs of it to his friends.

Morgan hung this portrait in the library of his house, behind the couch where he napped, and not in his study. Instead, his desk faced a portrait of his father, Junius Spencer Morgan, above the mantel. Holl’s portrait of Morgan was passed down through the family and given to the museum in 1967 by Pierpont Morgan’s grandson J.P. Morgan II (1918–2004).

Stop 26. Virgin and Saints Adoring the Christ Child

Pietro Perugino (Italian, ca. 1450–1523)

Ca. 1500

Tempera on panel

34 1/2 x 28 3/8 inches (876 x 721 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator of Drawings and Prints

Known for his graceful figures, Perugino was the leading painter from Umbria, a region in central Italy, during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Using harmonious jewel-like tones, the artist depicted the Virgin flanked by St. John the Evangelist and an unidentified female saint, perhaps Mary Magdalene. The inscription on the frame, referring to the Christ Child, is from Psalm 45: Fairer in beauty are you than the children of men; grace is poured out upon thy lips; thus God has blessed you forever. The elegant figures and delicate landscape are hallmarks of Perugino’s graceful style, which had a lasting impact on his most famous pupil, Raphael.

When Morgan was furnishing his study he pursued Italian paintings in earnest, working with many art dealers. This panel was procured for Morgan in 1911 by the British agent and critic Robert Langton Douglas from the Sitwell family, whose members are noted for their eccentric collections, many of which were housed at Renishaw Hall in Derbyshire, England.

Stop 27. North Room, or the Librarian’s Office

Sidney Babcock, Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen Curator of Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets

In early 1906, as construction of his Library neared completion, Morgan hired a young librarian to oversee its day-to-day affairs. Her name was Belle da Costa Greene. Her office is the intimate, two-story space opposite the entrance, now known as the North Room. The ceiling paintings were created in the studio of James Wall Finn, who based three of the horizontal panels on Renaissance examples, with the fourth replicating a ceiling painting in the Doge’s Palace in Venice by the eighteenth-century Italian painter Giambattista Tiepolo.

The perimeter of the ceiling is decorated with painted stucco reliefs, including twelve portraits based on Italian Renaissance medallions depicting ten men and two women who were among the great patrons of their era. The fireplace mantel, with its parade of misbehaving children, was provided by the Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini.

From this room, Greene managed acquisitions, cataloged the collection, and corresponded with dealers and scholars, until her retirement in 1948. The room served as the Director’s office until the late 1980s. The space was closed to the public until the 2010 renovation of the library when it was reimagined as a gallery for the Morgan’s collection of antiquities. It now features ancient western Asian seals and tablets, Egyptian and Greco-Roman sculpture, and early medieval ornaments from the Thaw Collection.

Stop 28. Belle Greene, Librarian

Baron Adolf de Meyer (1868–1946)

1912

Photograph

Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Erica Cialella, 2020–2022 Belle da Costa Greene Fellow

Born in 1879, Belle da Costa Greene was named Belle Marion Greener at birth. She grew up in a predominantly African American community in Washington, DC. Her father, Richard T. Greener, was the first Black graduate of Harvard College and a prominent educator and racial justice activist. After Belle’s parents separated, her mother, Genevieve Ida Fleet Greener, changed her surname and that of the children to Greene. While Belle was still in her teens, Genevieve and the children added “da Costa” to their surname and passed as a white family of Portuguese descent.

Greene and Junius S. Morgan II, Morgan’s nephew and advisor on Library matters, met at the Princeton University Library, where Junius was a librarian and Greene likely was a cataloger. In 1905, Junius enlisted Greene to prepare Morgan’s books for transport to the Library. On Junius’s recommendation, Morgan hired Greene to manage his “bookman’s paradise.”

Greene served as a de facto site manager while construction was in its final stages. She went on to run the Library for the rest of her working life, ultimately serving as the first Director of what is now the Morgan Library & Museum and remaking a private treasury into a center for scholarly inquiry and public engagement.

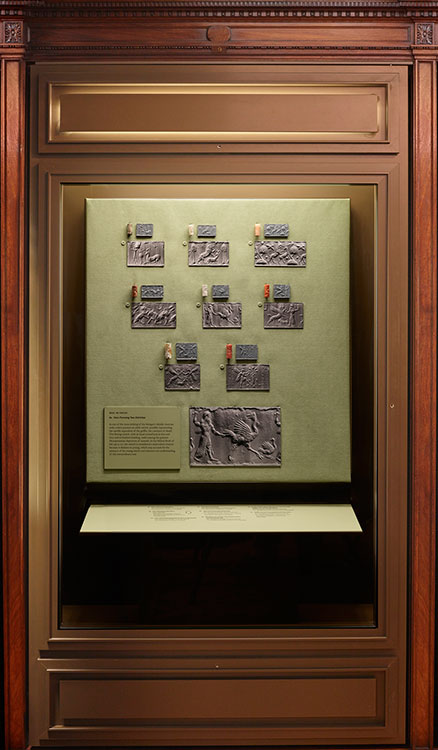

Stop 29. Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets

Sidney Babcock, Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen Curator of Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets

Pierpont Morgan’s collecting interests were broad, and the North Room display highlights his particular interest in cylinder seals from ancient western Asia. These are from the civilizations of

Mesopotamia, now modern-day Iraq. The earliest examples are more than five thousand years old.

Ancient Mesopotamian seals are among the first known objects to use pictorial symbols to communicate ideas. Many of the images represent human qualities and other concepts in the religious and poetic literature of ancient western Asia, including the Judeo-Christian Old Testament. Seals were engraved with scenes that appear in relief when rolled over clay. The impressed clay dried and hardened into a seal for doors, jars, boxes, and baskets. Their principal function in later times was to impress clay tablets on which records were inscribed in order to authenticate a document. Worn by their owners, seals offered protection and brought good luck.

A selection of seals from the Morgan’s collection are shown with modern impressions replacing the clay used in antiquity. Below each impression is a photographic enlargement that clarifies the detail and beauty of the carving. Despite being among the smallest objects produced by sculptors, seals feature imagery that enables us today to enter the visual world of the ancients.

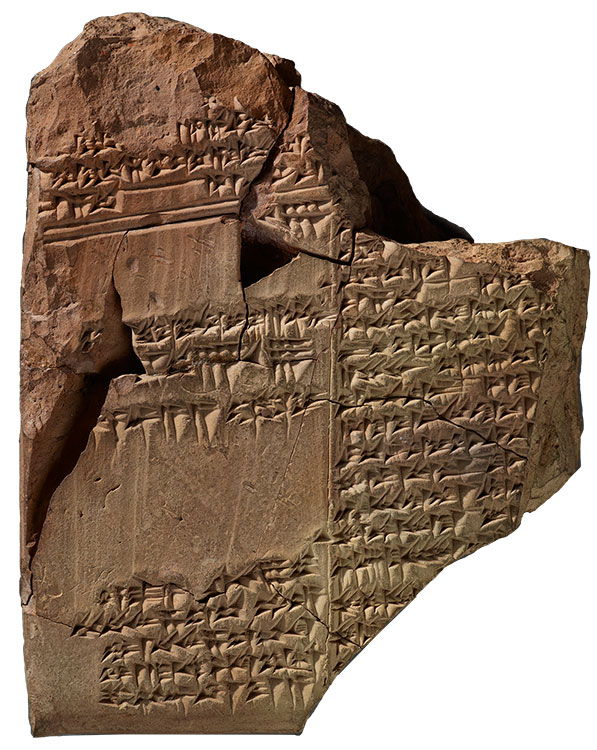

Stop 30. Earliest Account of the Deluge

Mesopotamia, First Dynasty of Babylon, reign of King Ammi-saduqa (ca. 1646–1626 BC)

Clay

114 x 90 mm

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan between 1898 and 1908.

Sidney Babcock, Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen Curator of Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets

The earliest known writing system was developed in southern Mesopotamia sometime during the middle of the fourth millennium B.C., when a system to keep track of the distribution of resources, such as produce and livestock, became an economic necessity. Using what they had at hand, the Mesopotamians took reeds from the riverbanks and adapted them as tools to impress into clay wedge-shaped marks that were then assigned meanings. This was an intellectual achievement that amounted to nothing less than the invention of writing. Cuneiform, from the Latin word cuneus, meaning “wedge,” evolved into a full-fledged, syllable-based writing system that was used for over three thousand years.

This precious fragment of a tablet is the earliest known version in the Akkadian language of the story of the Great Flood, familiar to many from the Christian Bible. The epic begins when the gods create man, though they soon tire of him and decide to destroy all of mankind. The god Enki (Ea) tells the mortal Atrahasis of the impending flood and instructs him to build an ark. With over 1200 lines, the story filled three tablets. The Morgan fragment, from the second tablet, preserves a unique statement with the work’s title—“When Gods Were Men”—as well as the name of the scribe and the place and date on which he copied it.

Translated into modern English, one passage reads:

The Flood roared like a bull,

Like a wild ass screaming the winds

The darkness was total, there was no sun…

For seven days and seven nights

The torrent, storm, and flood came on…

Stop 31. Bust of Giovanni Boccaccio

After Giovanni Francesco Rustici (Italian, 1475–1574)

Late 16th or 17th century

Bronze, mounted to marble

15 x 16 1/2 x 7 inches (381 x 419 x 178 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

Above the mantel in the North Room is a bronze bust of a smiling man in clerical garb, mounted on a white marble surround, and placed between two porphyry urns. While this bust has occupied an esteemed place in Belle Greene’s office since 1910, only in recent years has the sitter’s true identity been determined.

Morgan acquired the bust in 1909 and it was long thought to depict the Italian Renaissance poet Francesco Petrarca, or Petrarch. Yet the round face and jovial, smiling mouth struck curators as a curious way to depict the serene Petrarch. Research revealed that the bust is actually a bronze cast after a marble bust from the tomb of the Florentine poet Giovanni Boccaccio. The original bust was made by the Renaissance sculptor Giovanni Francesco Rustici in 1503. The Morgan’s bronze was likely cast when the tomb was moved, probably in the seventeenth century.

The work fits the description of Boccaccio by his contemporary Filippo Villani: “Tall and rather stout of build, Boccaccio had a round face with the nose slightly flat above the nostrils; rather large, but nonetheless attractive and well-defined lips; and a dimpled chin that was charming when he laughed.”

Stop 32. Running Eros, Holding a Torch

2nd or 1st century BC [200–0 BC?]

Bronze

23 3/16 inches (589 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1902

Joshua O’Driscoll, Associate Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

Morgan collected a vast number of antiquities, some from excavations that he sponsored. Most of these objects are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he served as president, or at the Wadsworth Atheneum, in his native Hartford, to which they were presented by his son, Jack, following Morgan’s death. During his lifetime, however, Morgan chose a select few antiquities to keep with him in his library.

Among his favorite objects was this bronze figure. This depiction of Eros as a winged child bearing a torch was excavated from the ruins of a cluster of Roman villas located in Boscoreale, a town buried in the same Mount Vesuvius eruption that destroyed nearby Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 AD. The theme of love and desire, personified by Eros, was a favorite decorative motif for garden statuary appropriate to the informal atmosphere of these ancient resort towns where many wealthy Romans had villas.

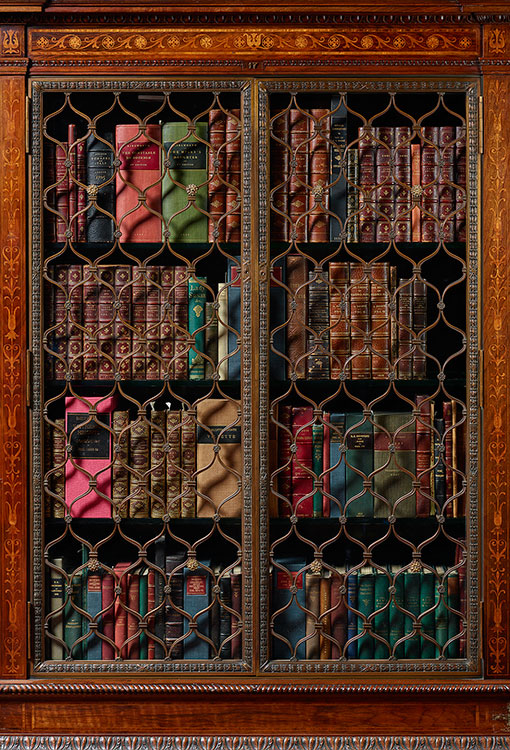

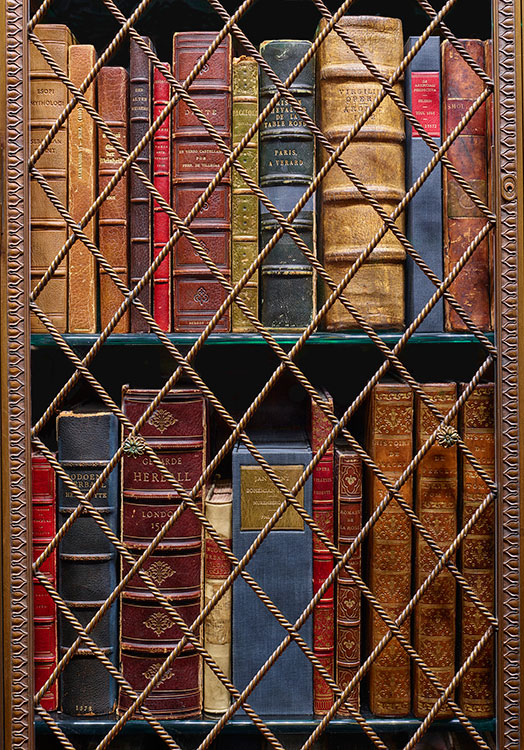

Stop 33. East Room

Jesse Erickson, Astor Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

The East Room is an architectural masterpiece designed to store and protect valuable volumes. This was the principal space Morgan used for entertaining groups and for sharing the works in his collection. Originally, Charles Follen McKim planned a single tier of bookcases to circle this room. But Morgan’s collections grew even as his Library was being built and two additional tiers were added.

Much of Pierpont Morgan’s original rare book collection is still shelved here, including early Bibles; first editions of Copernicus, Galileo, and others; and classics of French and American literature. The room holds eleven thousand volumes, only a fraction of the museum’s collection of more than one hundred thousand printed books. The majority of the rare books collection is now stored in a vault built as part of the Renzo Piano expansion.

Stop 34. Secret Staircases

Philip Palmer, Robert H. Taylor Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts

Charles McKim thought of everything in his design for Morgan’s Library—including a clever mechanism for reaching the upper balconies. On the ground floor, some of the bookcases near the entrance doors have brass handles. These cases are designed to pivot, revealing secret spiral staircases behind them that lead to the second and third tiers. These pivoting bookcases are used by librarians and curators when they remove works from the bookshelves for use by researchers or for display in an exhibition.

There is also a secret room concealed behind a bookcase in the southwest corner. The case pivots to reveal a small closet lined with deep shelves for storing the oversized volumes in Morgan’s collection. This space also has a “book elevator” which was used by librarians to transport heavy volumes safely from the upper tiers.

Stop 35. The Ceiling

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

The ceiling that soars above the bookshelves in this grand room is a complex creation. At the center is a large lay light, which was intended to let natural light into the room. It is surrounded by a cove ceiling joining it to the walls. The cove contains lunettes separated by spandrels, offering abundant surfaces for painted and stuccoed decoration.

Charles Follen McKim recruited the artist Harry Siddons Mowbray to develop the decorative program for the ceiling. Morgan, McKim, and Mowbray had been involved in the founding of the American Academy in Rome. All three had a deep appreciation of Renaissance culture that strongly influenced their vision.

Mowbray had carefully studied the great Roman villas and their interior decorative schemes, including their use of gold and stucco. For the lunettes, he chose reclining female figures representing the arts and sciences, based on sixteenth-century models. These alternated with portraits of male architects, painters, printmakers, philosophers, and others, from antiquity to the Renaissance, whom Mowbray selected to represent the leading contributors to Western civilization. To the right of the entrance is William Caxton—the first English printer. Originally, a lunette with Johannes Gutenberg represented the field of printing, but Morgan had recently acquired a collection containing thirty works by Caxton and so Gutenberg’s portrait was replaced.

Mowbray completed the ceiling design by placing the twelve zodiac signs in the spandrels. The zodiac was an important part of Renaissance culture, but it also had personal significance for Morgan, who was a member of a private dining association known as the Zodiac Club.

Stop 36. Triumph of Avarice Tapestry

Woven by Willem de Pannemaker (Flemish, ca. 1510–1581), after a design by Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Flemish, 1502–1550)

1534–36

Wool, silk, and gilt-metal wrapped thread

12 x 24 feet (4.43 x 15 m)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1906

Austėja Mackelaitė, Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator

The Triumph of Avarice is the only surviving tapestry from a series depicting the seven deadly sins that once belonged to the English king Henry VIII. The series was designed by Netherlandish artist Pieter Coecke van Aelst and woven with gilt-metallic thread in the Brussels workshop of Willem de Pannemaker. The king’s set was likely the first weaving of that series, dating to circa 1535.

As recounted in a sixteenth-century description, the Triumph of Avarice is full of historical references to the consequences of greed. At left, the winged and taloned Avarice emerges from Hell in a chariot drawn by a griffin; in her wake are Death, Betrayal, Simony (or the selling of pardons), and Larceny. At center, King Midas, with his donkey ears, rides on horseback, carrying a branch. The powerful ruler had been granted his wish of turning everything he touched into gold, which ultimately led to his demise. In the background are King Croesus, famed for his fortune, and Polymestor, the ancient Greek ruler who killed King Priam’s son in order to steal his treasure. On horseback at right is Pygmalion, whose digging symbolizes the search for earthly treasures.

Strewn on the ground are the bodies of three victims who died because of their gluttony. The cartouche at top bears a Latin inscription reminding the viewer, “As Tantalus is ever thirsty in the midst of water, so is the miser always desirous of riches.”

Stop 37. Stavelot Triptych

Triptych containing two small Byzantine triptychs on the center panel. Meuse River Valley.

Ca. 1156–58

Wood panels with copper-gilt frames, silver pearls and columns, gilt-brass capitals and bases, vernis brun domes, semi-precious stones, intaglio gems, beads, champlevé and cloisonné enamels

19 inches (484 mm) x 26 inches (660 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Joshua O’Driscoll, Associate Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

According to legend, the True Cross, on which Christ was crucified, was discovered in Jerusalem by St. Helena (ca. 255–330), mother of Constantine the Great (ca. 272–337), the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. Helena brought the cross to Constantinople, where for centuries it served as the source for precious gifts from the Byzantine emperors. Abbot Wibald of Stavelot (d. 1158), in modern-day Belgium, commissioned this triptych. Wibald traveled to Constantinople in 1155 to 1156 to negotiate a marriage for Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, and the two small triptychs on the center panel were likely gifts acquired on that diplomatic mission.

The lower reliquary features splinters of wood arranged to form a cross. The upper reliquary contained a pouch with a fragment of the Virgin Mary’s garment and dirt from the Holy Sepulcher in a cavity. These relics are now preserved separately.

The wings of Wibald’s triptych feature enameled scenes of exceptional quality depicting the Legend of the True Cross. The story begins at bottom left, with Constantine having a vision of the cross in his sleep. Above, he defeats his rival Maxentius, using the cross as his battle standard. Constantine then accepts Christianity and is baptized by Pope Silvester. The three roundels on the right side tell the story of Empress Helena and her discovery of the True Cross. From the bottom, they show Helena interrogating the Jews, discovering three crosses, and then identifying the True Cross through the miraculous resurrection of a dead youth. Implicit in these roundels is the idea that Jews were responsible for Christ's crucifixion, a link which has had a devastating effect on Jewish communities for centuries.

Stop 38: On the Shelves

Jesse Erickson, Astor Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

While this room was designed with one tier of bookshelves, the scale of Morgan’s collections necessitated blocking up windows and the addition of two further tiers. The shelves along these walls contain just part of the Morgan’s vast collection of rare printed books. The collection ranges from the earliest examples of printing, called incunables, made in the fifteenth century, to first editions by authors living today.

Much of what you see was originally collected by Pierpont Morgan himself. While he did acquire large caches and whole libraries, Morgan was primarily looking for books that had something special to offer: distinguished provenance, an author’s annotations, or a rare binding, features that would make a printed book, which was produced in multiples, a unique object.

The collection has grown and developed since Morgan's original acquisitions. In the bookcases to either side of the fireplace are more-recently donated collections, including, on the left, the Elisabeth Ball Collection of Early Children's Books, and, on the right, the Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection of literary and scientific volumes.

Stop 39. The Role of Conservation

Maria Fredericks, Sherman Fairchild Head of the Thaw Conservation Center

Most of the objects in the Morgan’s collection are on paper or parchment, some with delicate pigments or dyes that can change or fade with too much exposure to light. Because of this inherent fragility, most of our treasures can only be displayed for a few months at a time, under controlled lighting conditions. Frequently rotating our installations helps preserve our collections and also allows us to highlight the vast range of our holdings.

To preserve our collections for future generations, we have a team of conservators and preparators who specialize in paper, parchment, and book bindings. Located in the Morgan’s Thaw Conservation Center, they are responsible for making sure collection objects are safely housed and displayed. We also evaluate and treat objects that have deteriorated or have been damaged. We monitor the temperature, humidity, and light levels in our galleries and vault spaces, to ensure that conditions are optimal for preservation. With over half a million items under our care, and more than one thousand works shown in our galleries each year, the Morgan’s conservation staff plays a critical role in preserving and presenting the museum’s collections.

Stop 40. The Gutenberg Bible

Biblia Latina

Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg & Johannes Fust

Ca. 1455

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1896.

John McQuillen, Associate Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

The technology of printing texts and images had long been practiced in Asia, but by around the year 1400, Europe had only the technology to print images. The European development of printing texts with movable type was introduced in the early 1450s by Johannes Gutenberg, his assistant Peter Schoeffer, and Johannes Fust in Mainz, Germany. This large Latin Bible, referred to as the Gutenberg Bible, is the first substantial work produced on a printing press in the West. Prior to Gutenberg, it could take a scribe nearly a year to write out one copy of the Bible by hand. However, with the advent of the printing press, several hundred copies of a book could be produced within a few weeks or months, which significantly impacted the spread of information and development of literacy.

Gutenberg printed 180 copies of the Bible, some on paper and some on the more expensive animal skin, known as vellum or parchment; only forty-eight copies still exist today, and three are at the Morgan. Pierpont Morgan acquired his first copy in 1896 from the London bookseller Henry Sotheran. This copy is printed on vellum and adorned with hand-painted decoration produced in Bruges, Belgium, around 1460, but with heavy nineteenth-century restorations. Four years later, Morgan obtained a second copy through the purchase of the library of Theodore Irwin. The Irwin copy is printed on paper and was decorated by a local artist in Mainz, but it comprises only the Old Testament.

Finally, in 1911, Morgan was able to acquire at auction a complete paper copy in pristine condition. The red and blue painted initials indicate that this copy was originally owned by the monastery of Kirschgarten near Worms, Germany, just south of Mainz along the Rhine river. In honor of the importance of this pivotal invention to the history of the book in western culture, one of the Morgan’s volumes is always on display.

Stop 41: Librarian’s Work

Philip Palmer, Robert H. Taylor Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts

While the East Room is the showpiece of the building, it is also very much a working library, with a number of conveniences designed to enable the daily tasks of librarians. During the planning stage, Morgan’s nephew Junius explored the use of specially designed hinges that would allow the doors on the bookcases to open fully, maximizing shelf space and allowing for easy retrieval of books. The cases also come with a lock to secure their contents. While the two upper tiers were designed with brass railings, concern for the safety of librarians pulling volumes from the lower shelves led to the addition of bronze guard rails. A book elevator was installed in one of the concealed spaces to allow safe transportation of heavy tomes to and from the upper tiers.

Belle Greene’s office also contained several innovations to make her work efficient. She had custom-built card-catalog cases to facilitate her work documenting and organizing the collection, and a chair that could swivel, allowing her to manage several tasks at once. A custom-designed telephone table also fostered ease of communication with Morgan and with a wider circle of colleagues and dealers.

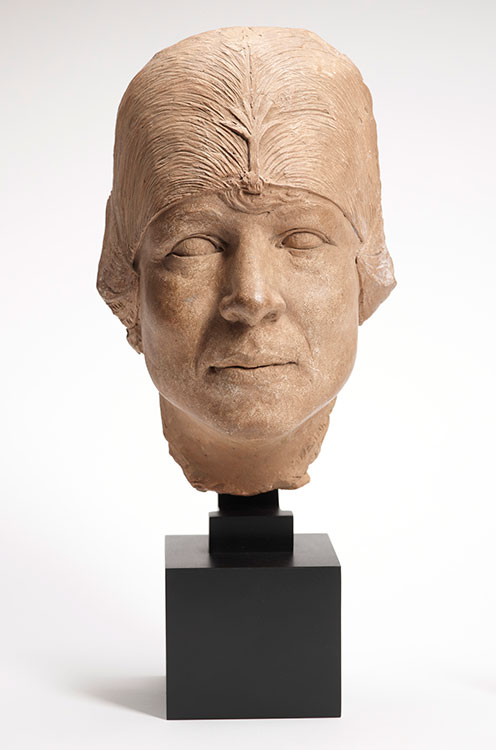

Stop 42. Bust of Belle Greene

Jo Davidson (American, 1883–1952)

1925

Terra cotta

11 x 7 x 5 3/4 inches (27.9 x 17.8 x 14.6 cm)

Purchased on the Charles Ryskamp Fund, 2018

Rachel Federman, Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Drawings

A sculptor well known for his portraits, Jo Davidson made numerous busts of writers, artists, and political and military figures during the first half of the twentieth century. This terra-cotta bust of Belle da Costa Greene was recently rediscovered in Davidson’s estate and acquired by the Morgan in 2018. Like many of Davidson's portraits, it was probably not a commission but, rather, one of the busts he made when he encountered someone whose face he found interesting. Davidson may have met Belle Greene through publisher and bibliophile Mitchell Kennerley, who was a close friend of them both, especially in the mid-1920s, when this bust was made. This is the only known sculpted portrait of the first Director of the Morgan and one of the few surviving life portraits of her in any medium.

Stop 43. St. Elizabeth Holding a Book

St. Elizabeth Holding a Book

Germany, Ulm (Swabia)

Early sixteenth century

Lindenwood, with polychromed and gilt decoration

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan in 1911

An inscription on the gown of this elegantly carved figure identifies her as St. Elizabeth. The foundry mark of the Ulm cathedral architects is located on her hem and sleeve, suggesting the sculpture’s origin. She may represent St. Elizabeth of Schönau (1129–1165), a German nun who published three volumes describing her divine visions, instead of the more well-known thirteenth-century St. Elizabeth of Hungary (1207–1231), who is typically depicted holding roses or distributing alms. The statue was restored in the nineteenth century, and the hands and book may date to that period.

Stop 44. The Annex

When Pierpont Morgan died in 1913, he left his vast collections as well as the magnificent library he built next door to his home to his son, J. P. Morgan, Jr., who was known as Jack. The younger Morgan gave many of the works of art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Wadsworth Atheneum, in Hartford, Connecticut. He kept the books, manuscripts, drawings, and prints, among other collections, and formed a public institution to make these collections available.

In 1924, following his mother’s death, Jack Morgan commissioned the Annex, a building containing space for exhibitions and scholarly research on the site of his parents’ home, adjacent to the original Library. He hired the architect Benjamin Wistar Morris to design it. Morris took his cues from the Charles Follen McKim building next door but did not try to compete with McKim’s Renaissance-style palace. A long narrow gallery connected the two buildings, where the modern Clare Eddy Thaw Gallery is today.

The project took four years, and the Morgan opened its doors as a public institution in October 1928.

Stop 45. Inside the Annex: Yellin and Mowbray

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

The Marble Hall served as the entrance to the Morgan Library from 1928 until 2003. Two galleries flank the hall. Originally, one was for exhibitions and the other was a scholars’ reading room. Today, both are exhibition galleries—the reading room is now on the third floor of the central pavilion designed by Renzo Piano, where it is open to researchers by appointment.

The ceiling in this space is characterized by decorative ironwork. Created by the prominent Philadelphia blacksmith Samuel Yellin, it features nearly 650 birds—each one unique.

When completing the interior of the Annex, Jack Morgan enlisted Harry Siddons Mowbray, who created the ceilings in Morgan’s original library building more than twenty years earlier. Mowbray was charged with decorating the ceiling of a small vestibule that led from the entrance hall to the garden and passage to the Library. It now connects the Annex to the center of the Morgan campus.

The appearance of the vestibule ceiling decorations is strikingly different from the paintings in the Library. Howard Carter’s discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922 fueled an Egyptian revival in America in the 1920s. This fashionable interest in the subject matter and aesthetics of ancient Egypt and the surrounding “biblical lands” is seen in Mowbray’s Annex ceiling.

The overall theme of the ceiling is a celebration of ancient cultures that contributed to the advancement of human knowledge and Western civilization: the Greeks and Phoenicians, the Persian emperors Darius and Cyrus, Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III, ancient prophets, and early Christians. Among the scenes represented are Osiris teaching the art of agriculture and Darius installing the postal service. Mowbray and his workshop completed these paintings shortly before the artist’s death in January 1928.

Stop 46. The Lower Level

The lower level of the Renzo Piano expansion contains two very important elements of the Morgan campus—the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Education Center, serving school groups, and the Gilder Lehrman Hall, a state-of-the-art performance venue. The lobby between these two spaces contains a rotating display of oil sketches from the collection of Trustee Eugene V. Thaw, a case featuring changing focused displays from the collection, and several works of painting and sculpture on permanent view.

Out of sight but adjacent to the auditorium—nestled into the bedrock—is perhaps the most important feature of our facility: the main vault. Nearly fifty thousand tons of Manhattan schist were excavated to create a secure, climate-controlled storage space for the Morgan’s precious collections. As Renzo Piano noted, “We put the treasure in the most safe place you can find in Manhattan—in the rock.”

By building down, Piano was also able to keep the above-ground part of his design modest in its proportions. His scheme allowed the Morgan to expand its exhibition and program space, but without running the risk that the new structures would overshadow the existing historic buildings.

Stop 47. Morgan's Legacy

A Lady Writing

Johannes Vermeer (Dutch, 1632–1675)

Ca. 1665

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Colin B. Bailey, Director

Beginning in 1912, the contents of Pierpont Morgan’s London home at Princes Gate; his English country retreat, Dover House; and the many collections he had placed on view in London museums were created for transport. These collections were shipped to New York via the White Star Line. Their ultimate destination had not yet been decided.

After Morgan’s death, his son, J. P. Morgan, Jr., called Jack, was faced with the task of determining the fate of his father’s collections. Eventually, most were given to museums Morgan had championed, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Wadsworth Atheneum. A group of intimately scaled work was kept to form the core of what is now the Morgan Library & Museum, while the majority of Morgan’s paintings were inherited by Jack and his sisters Louisa, Juliet, and Anne. Many, including Vermeer’s A Lady Writing, now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, later entered American museums.

Portions of Morgan’s collections were sold after his death, nourishing other collections, including that of Henry Clay Frick, who bought large holdings of Chinese porcelains, Renaissance bronzes, and paintings such as the Progress of Love series of panels by Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

Stop 48. The Morgan House

Jack Morgan’s Brownstone

The oldest structure on the Morgan campus is the Morgan House, at the corner of 37th Street and Madison Avenue. Built in 1854, it is a rare example of a freestanding brownstone. Pierpont Morgan lived in a house at the corner of Madison and 36th Street. He was able to purchase the house in the middle of the block and then this brownstone in 1903–1904. He tore the house down in the middle to create space for a shared garden and had the brownstone renovated before giving it to his son Jack, and Jack’s wife, Jane Norton Grew Morgan, and their children. They lived here from 1905 until 1943.

This brownstone may not look impressive from the outside—certainly it doesn’t rival the Fifth Avenue palaces of other wealthy New Yorkers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But with its renovated George III interior, forty-five rooms, twelve bathrooms, and twenty-two fireplaces, it was clearly the home of a wealthy man. In 1936, Jack Morgan hosted a crowd of five hundred in the ground-floor parlors, one of which is now part of the Morgan Shop.

After Jack’s death in 1943, the building was purchased by the Lutheran Church. The Morgan acquired the property from the church in 1988, and originally incorporated it into the museum with a glass courtyard designed by Voorsanger and Mills; the courtyard was later replaced by Renzo Piano’s 2006 expansion, which further integrated the campus. Today, the main floor contains the Morgan Dining Room and the Shop, while the rest of the rooms serve as offices for much of the Morgan’s staff.

Stop 49. Dining and Music Rooms

Robinson McClellan, Assistant Curator of Music Manuscripts and Printed Music

After acquiring Jack Morgan’s brownstone in 1988, the Morgan refurbished the interior which had suffered from decades of neglect. Preserved on the ground floor are the former music rooms, clad in wood paneling with carved and gilt decorations depicting musical instruments. One room is now part of the Morgan Shop.

The restaurant was once the dining room used by Jack and Jane Morgan and their family. The architectural details are mostly original, and the portraits on the walls show members of the Morgan family. On the left side is Joseph Morgan, Pierpont Morgan’s grandfather and Jack’s great-grandfather. Joseph’s wife, Sarah, faces him from the opposite wall. Over the marble fireplace hangs a portrait of Pierpont Morgan as a child, with his sister Sarah Spencer Morgan.

The rest of the Morgan House is mainly museum offices, and the top floor is home to the Thaw Conservation Center, a world-class laboratory for the study and treatment of works on paper and parchment.

Stop 50. 36th Street Promenade Exterior

Colin B. Bailey, Director

If you exit the Morgan and walk along 36th Street, you will be able to enjoy the architecture of Benjamin Wistar Morris’s Annex, Renzo Piano’s Thaw Gallery, and McKim, Mead & White’s original Library as you head east. A delightful surprise is the newly conceived landscaping that surrounds these buildings, designed by landscape architect Todd Longstaffe-Gowan and unveiled in summer 2022.

Stop 51. The Façade

Colin B. Bailey, Director

From 1902 to 1906, hundreds of people worked to fulfill Morgan’s commission and realize McKim’s design, from the quarrymen who extracted the stone in east Tennessee to the masons who set the blocks with exquisite precision. More than a century later, a contemporary team of specialists has honored their labor by restoring this well-made building, cleaning and repairing the façade, statuary, and front doors, as well as the elegant bronze perimeter fence. The restoration respects and enhances the restrained façades of both the original Library and Renzo Piano’s addition.

Stop 52. Edward Clark Potter’s Lionesses

Aside from a collection of books, what does the J. Pierpont Morgan Library have in common with the New York Public Library (NYPL) on 42nd Street? Our lions!

The lionesses that flank the original entrance to our Library building were created by the acclaimed sculptor, Edward Clark Potter, who also created the lions at the entrance of the NYPL. The lions at the NYPL were completed in 1911, several years after our library and lionesses were completed and remain an important marker of our library building today.

During the restoration of our library building, our lionesses have also received some special treatment. After spending several months in hibernation protected by protective boxes, our duo received a thorough cleaning, followed by a surface treatment to ensure they are protected for years to come. Both of our lionesses had their ears renewed through a hand-carved dutchman repair to fill loss that occurred over the years. The restoration has given a new life to our lionesses, who are ready to continue guarding our building for years to come.

Deirdre Jackson, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

McKim’s friend Daniel Chester French, one of the most prominent American sculptors of the day, recommended that the architect engage Edward Clark Potter to sculpt the marble lionesses that grace the Library’s entrance. In 1903, Potter was awarded a commission of $10,000 to sculpt the female guardian lions that would be placed on inclined pedestals on either side of the front steps. He sketched live models at the new Lion House at the Bronx Zoo and then sculpted a lioness in clay in his studio in Greenwich, Connecticut. Next, plaster models were made to guide the stonecutter, who worked with large blocks of Tennessee marble. Potter likely hired John Grignola, an accomplished Italian immigrant carver, to execute the work.

Potter went on to sculpt the celebrated male lions that were installed outside the New York Public Library in 1911.

Stop 53. Entrance Doors

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

Though the doors to the Morgan Library evoke Italian Renaissance precedents such as Lorenzo Ghiberti’s doors for the Florence Baptistery, they were a modern creation. Likely the work of American sculptor Waldo Story, the doors were sold through the Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini and his agents and passed through a series of dealers before reaching New York. They were installed at the Library in October 1904. Their purported Renaissance origins, masking their contemporary creation, led to confusion that has only recently been clarified through archival research.

The heavy wood doors are made of walnut with mahogany moldings. Each measures nine-and-a-half feet tall and is adorned with cast bronze panels that depict scenes in the life of Christ. A modern touch is the doorbell, which is cleverly concealed in one of the perimeter rosettes at right.

See video: Restoration of J. Pierpont Morgan's Library: Doors

Stop 54. Loggia Sculpture and Reliefs

John McQuillen, Associate Curator of Printed Books and Bindings

McKim’s design for the exterior of the Morgan was austere, with a few additions of sculpture and decorative flourishes mostly reserved for the porch. The effect is even more spartan than initially proposed, since the niches in the façade were never filled with sculpture and the ones on the porch are occupied solely by marble figures purchased in 1909.

Visitors to J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library entered through a bronze gate along 36th Street and ascended a short flight of steps to the loggia. As they approached the massive doors, they stepped across slabs of rose and green marble, the only touches of color against the pink-white blocks of the building’s exterior. Looking up, they would have seen a vaulted ceiling adorned with marble carvings of notable printers’ marks.

The relief in the half-circle above the doors depicts the mark of the Aldine Press, the celebrated publishing house of the Venetian scholar and printer Aldus Manutius. It was designed by McKim, Mead & White, modeled by Andrew O’Connor, and carved by the Piccirilli brothers, New York’s most distinguished Italian immigrant stone carvers.

O’Connor, an Irish American artist, was commissioned to execute much of the Library’s exterior relief sculpture, but his contract was scaled back when he failed to progress quickly enough to satisfy McKim and Morgan. After O’Connor was relieved of his commission for the rectangular exterior reliefs, Adolph Weinman stepped in to design them.

Stop 55. The Garden

Jessica Ludwig, Deputy Director

Following Renzo Piano’s shift of the museum’s entrance from 36th Street to Madison Avenue, the exterior of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library was not as prominent a part of a visit to the Morgan. A project begun in 2016 and completed in 2022 aimed to revitalize this part of the campus and enable visitor access to the site through a restoration of the building’s exterior and a rethinking of the surrounding landscape.

Landscape designer Todd Longstaffe Gowan developed a plan that respects the structures created by McKim and Piano while encouraging engagement with the architecture and opening up new spaces for programming. A generous lawn sweeps across the space between the Annex and the Library. Paths of bluestone, set in patterns that derive from the Library’s floor and exterior paving, provide a fully accessible surface for garden visitors. Elegant pebble work and beds of periwinkle flanking the Library’s loggia add texture and color. Incorporated into the newly designed garden are several antiquities collected by Morgan which were intended for outdoor display. A significant component of the project is new lighting, which will enhance the building’s presence at night and whose subdued design refers to the Library’s origin as a private space.

See video: Restoration of J. Pierpont Morgan's Library: Garden Development

Stop 56. Garden Sculpture

Sarcophagus

Roman

Ca. 275

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan before 1913.

Deirdre Jackson, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

At the center of the lawn outside the Thaw Gallery sits a Roman sarcophagus, which dates to the third century, during the time of the Roman Empire. This lenos, or tub-shaped, sarcophagus is decorated with S-shaped grooves that resemble a strigil, the curved metal blade used by athletes to scrape dirt and oil from their bodies. The ends of the stone container feature lions attacking their prey, a popular motif for funerary art. Roman sarcophagi would have been placed inside a mausoleum, with the undecorated back against the wall.

In 1912, Pierpont Morgan engaged Beatrix Jones (later Beatrix Farrand), to design a garden for the space behind his home and library. The garden featured antiquities positioned on the lawn and as focal points along pathways. Todd Longstaffe-Gowan has reprised the spirit of the earlier garden, embedding several antique marble sculptures acquired by Morgan among the pebbled paths and on the lawn.

Stop 57. Well-Head

Venetian

15th century

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1912.

This well-head is thought to be the work of a fifteenth-century Venetian sculptor. It bears the coat of arms of the Morosini family, a celebrated Venetian clan that gave rise to various doges and diplomats. The family’s most notorious descendant, however, was Francesco Morosini, who in 1687 destroyed the Parthenon and plundered Athens for antiquities.

Pierpont Morgan acquired the marble on June 13, 1912, from the Venetian bookdealer Ferdinando Ongania, who shipped it to New York. Librarian Belle Greene noted on the invoice that it was intended for the Library, indicating that Morgan must have purchased it to embellish the grounds.

Early designs for the building show fountains where this and another well-head are now placed, but a photograph taken before 1924 shows at least one of the well-heads already installed in the spot. Landscape architect Todd Longstaffe-Gowan respected the historic placement of these objects when designing the pebble-work, paths, and beds that flank the walkway to Morgan’s Library.

Stop 58. Grave marker of Annia Secunda

Roman

Ca. 100-200

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan before 1913.

Deirdre Jackson, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

At the end of this bluestone path sits a Roman grave marker, or stele. The stone commemorates the life of an individual named Annia, who was a freedwoman, a low-status freeborn woman in ancient Rome. It was dedicated by her husband, Lucius Sempronius. The inscription reads: To the divine spirits. Lucius Sempronius Elatus (made this) for his most pious spouse, Annia Secunda. The back of the stone bears a second dedicatory offering: To the divine spirits, for Lollia Staphyle. The stele dates to the second century, a time of political upheaval and prolonged crisis for the empire.