Intimate Interiors

Barton led a peripatetic life, often traveling and otherwise staying in rented rooms in San Francisco and the bohemian enclave of Sausalito. No feature of these modest spaces escaped his observation. He lavished as much care on representations of light sockets and bedsprings as he did on portrayals of human figures. At times he focused on just a few details, but often he corralled crowded interiors into complex, fractured compositions. He compared himself to a spider spinning its web. Like the French artist Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Barton depicted his own earlier works within new drawings. He also frequently inserted himself engaged in the act of drawing into his compositions, underscoring the sense of an interior world consumed by art.

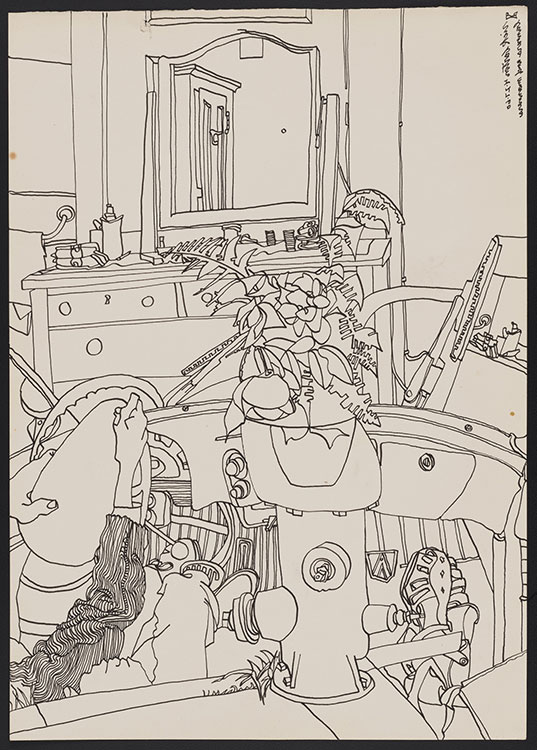

Untitled [Bed with reclining figure andmusicians]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Bed with reclining figure and

musicians], 1962

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Sink and chair]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Sinknd chair],

September 1962

Pen and ink with grap

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

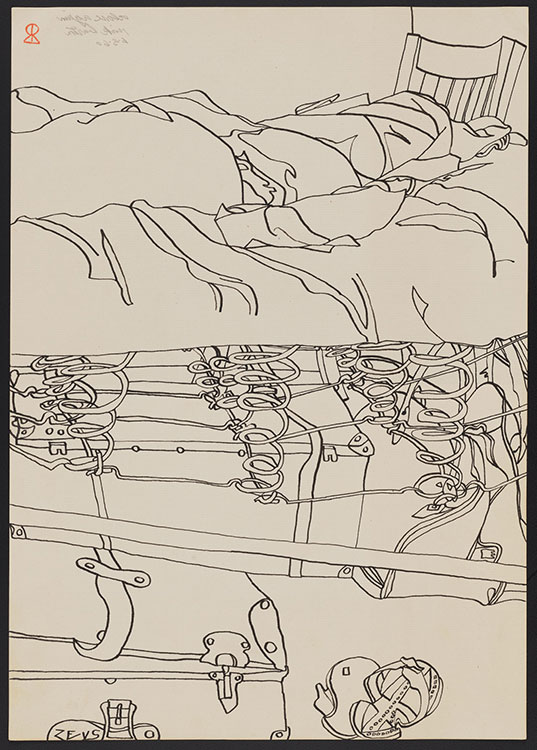

Alone Again

Here Barton dissects the layers of his bed, from the crumpled sheets on top to the intermediary bedsprings and frame, down to suitcases and sandals on the floor. Even without its heartbreaking inscription, “Alone again,” this peculiar visual inventory conveys a sense of solitude and itinerancy.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Alone Again, June 3, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

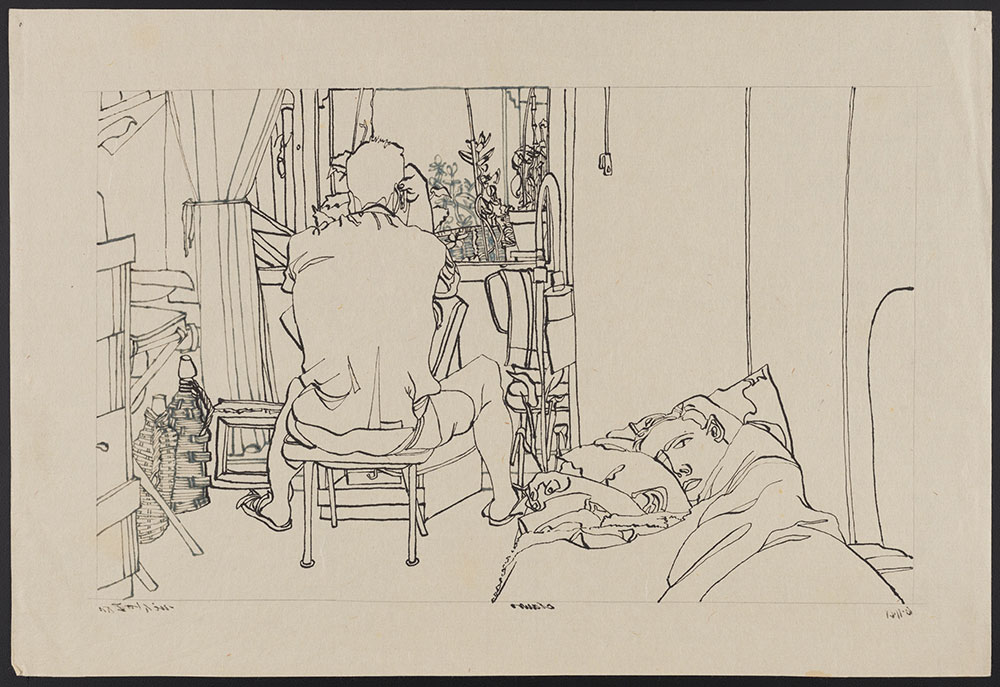

Untitled [Two figures]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Two figures], June 11, 1961

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Portrait of Russ Zerbe

This sheet is filled with figures and drawings of figures, making it difficult to distinguish between the representation of subjects and the representation of the representation of subjects. Russ Zerbe, who was a lover of Barton’s, is identified as the sitter in the composition’s central portrait; Zerbe may be shown elsewhere in the room as well. Compositions such as these suggest that drawing was the primary lens through which Barton experienced the world.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Portrait of Russ Zerbe, 1962

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Interior with fishbowls and map]

Barton kept aquariums in his childhood bedroom. The image of the adolescent artist in his room surrounded by fishbowls presages a larger current in Barton’s art: his tendency to reflect, refract, and displace his surroundings, as if they were being viewed through a glass or another vessel filled with water.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Interior with fishbowls and map], February 5, 1962

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Nudes]

This drawing points to an affinity with the early work of Andy Warhol. Barton addressed some of the same subjects that Warhol did—notably, beautiful youths and flowers—in a similarly delicate linear style. It is conceivable that Barton was familiar with Warhol’s early drawings, which were exhibited in New York and circulated— though not widely—through self-published books in the early 1950s, before Barton moved to the Bay Area.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Nudes], October 5, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

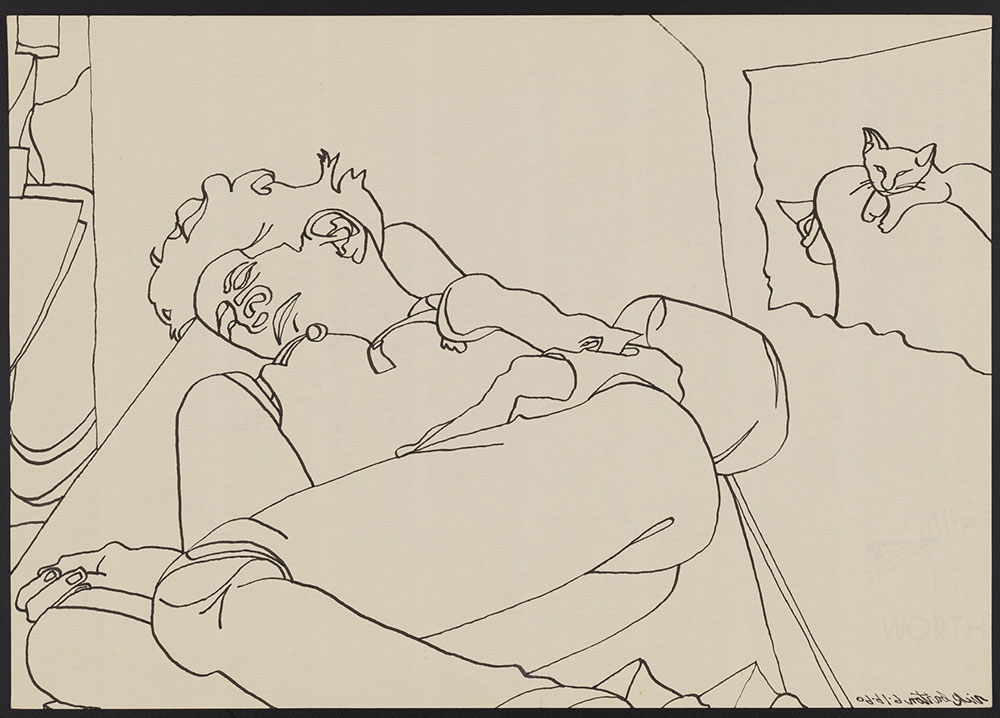

Untitled [Sleeping man]

Along with several others, this work suggests that Barton was familiar with the drawings of Jean Cocteau. The French avant-gardist’s unflinching depictions of gay subjects, including bars that he frequented, would certainly have been of interest to the young American artist, as they were to his contemporary Andy Warhol. This tender drawing of a sleeping man resembles a series of drawings that Cocteau published of his lover Raymond Radiguet, a writer, in the 1920s. (Barton’s drawing of leaves on the sheet’s reverse is visible.)

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Sleeping man], 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Again the Angel of the Celestial Bells

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Again the Angel of the Celestial Bells,

August 15, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

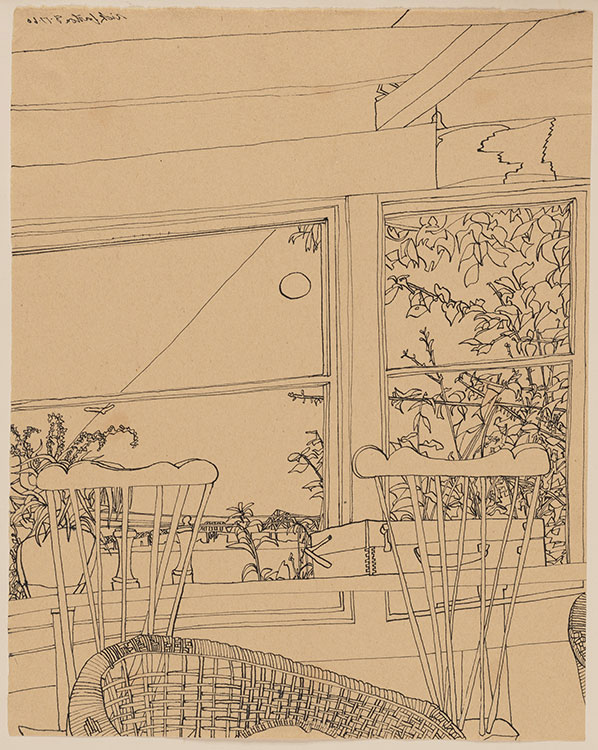

Untitled [Window]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Window], August 17, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Studio I

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Studio I, June 11, 1961

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Banners and Manners

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Banners and Manners, April 27, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Disembodied head]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Disembodied head], April 8, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Bedroom concert]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Bedroom concert], 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Rick Barton's Chinese Line

Barton adored classical music, which he often listened to while he drew. In this drawing, the domestic setting is signaled by a bookshelf, a section of paneled wall, and an unadorned lightbulb hanging from a chain. At left, violinists and a cellist surround a piano; an audience hovers around them. The line forming the headless piano player’s left arm extends from the milk poured by a rendering of the Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer’s Milkmaid (ca. 1660). In Barton’s world, line was capable of stitching together past and present, painting and music, and perhaps most importantly, art and life.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Rick Barton’s Chinese Line, April 25, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

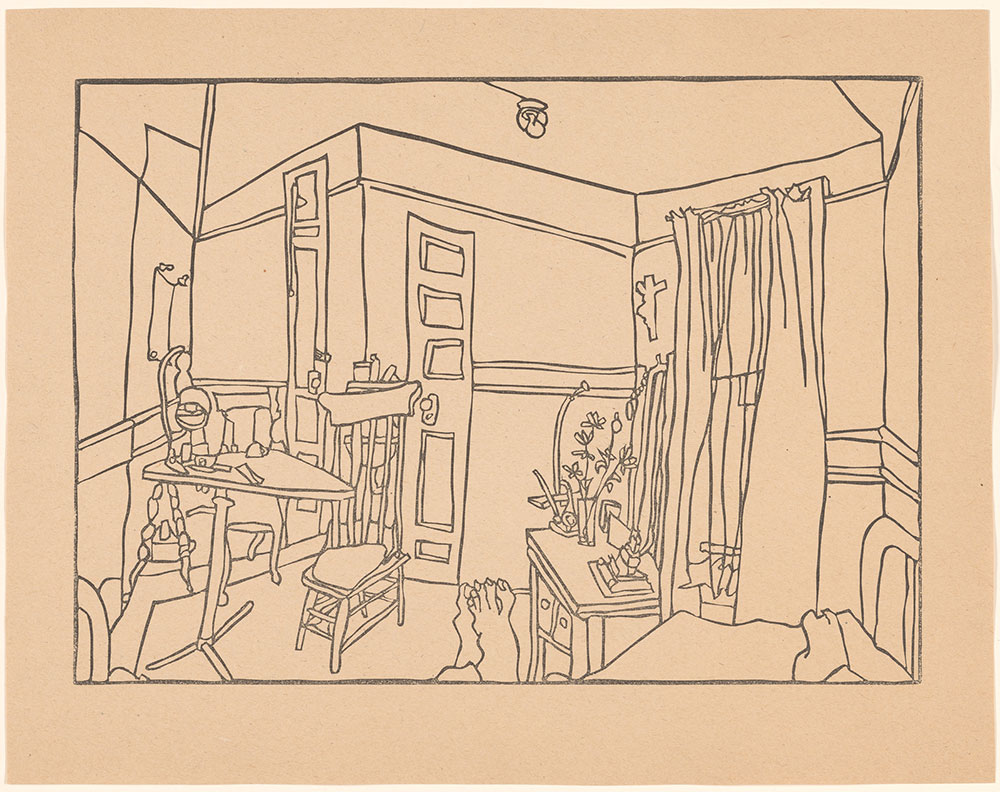

Rooms, plate 2

Barton had worked as a printer’s apprentice as a boy, but it was not until he met Henry Evans that the artist began to produce his own prints. Using linoleum blocks that Evans provided, Barton cut prints in a linear style similar to that of his drawings. The plates in this portfolio, printed by hand at Evans’s Peregrine Press, portray a range of rooms, from the spare interior at left, in which Barton’s feet are visible, to the more sumptuously decorated space at right.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Rooms, plate 2

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1958, published 1960

10 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 60

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony; 2017.277

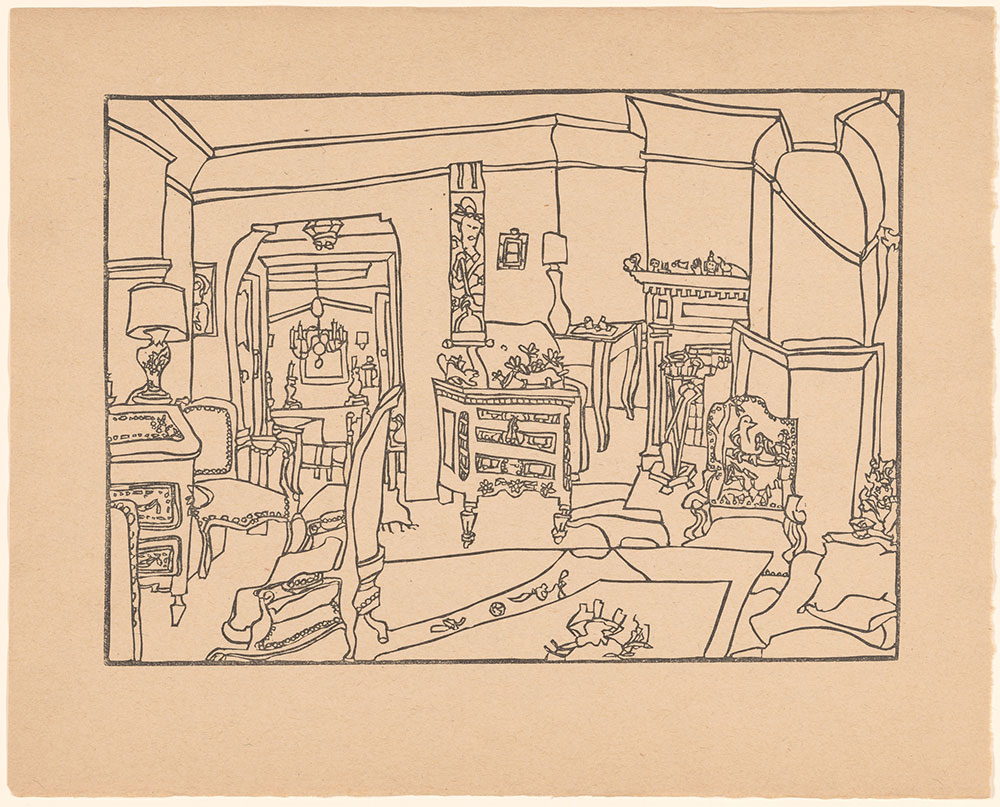

Rooms, plate 4

Barton had worked as a printer’s apprentice as a boy, but it was not until he met Henry Evans that the artist began to produce his own prints. Using linoleum blocks that Evans provided, Barton cut prints in a linear style similar to that of his drawings. The plates in this portfolio, printed by hand at Evans’s Peregrine Press, portray a range of rooms, from the spare interior at left, in which Barton’s feet are visible, to the more sumptuously decorated space at right.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Rooms, plate 4

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1958, published 1960

10 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 60

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony; 2017.277

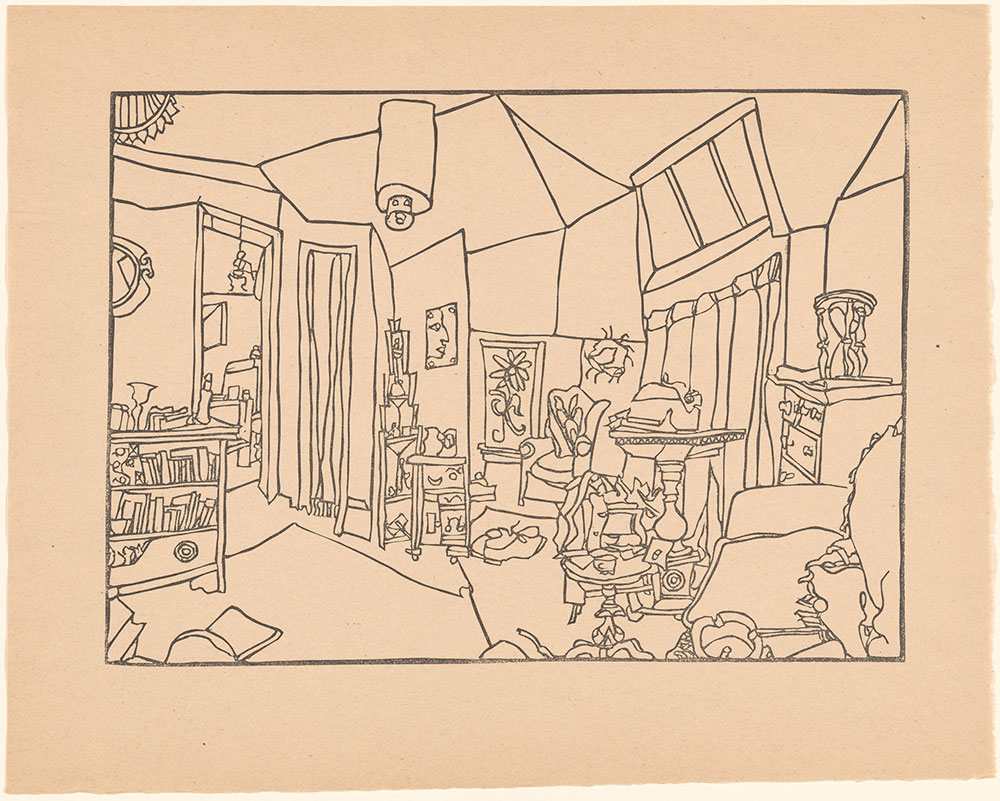

Rooms, plate 7

Barton had worked as a printer’s apprentice as a boy, but it was not until he met Henry Evans that the artist began to produce his own prints. Using linoleum blocks that Evans provided, Barton cut prints in a linear style similar to that of his drawings. The plates in this portfolio, printed by hand at Evans’s Peregrine Press, portray a range of rooms, from the spare interior at left, in which Barton’s feet are visible, to the more sumptuously decorated space at right.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Rooms, plate 7

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1958, published 1960

10 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 60

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony; 2017.277