Expression through Ornament

In addition to painting portraits and designing prints, Holbein composed small ornamental patterns and allegorical images for fabrication by goldsmiths. Holbein’s drawings in pen and wash presented plans for intricate pendants, hat badges, clasps, and gold-and-enamel book covers that adopted patterns and motifs popular in English and European decorative arts. Noble, wealthy individuals commissioned jewels and wore them prominently as expressions of their status and erudition. Many jewels featured emblems, also known as devices—motifs that served as visual representations of aspirations and values. Although no jewels designed by Holbein survive today, sixteenth-century French and English pendants and hat badges, on view here, demonstrate the sophistication and finesse of these precious objects.

This section also features An Allegory of Passion—a large, enigmatic painting whose lozenge format is unique in Holbein’s oeuvre. The work draws on the artist’s talent for ornaments and emblems and might have been created for a courtier with an interest in the poetry of Francesco Petrarch, the fourteenth-century Italian writer and scholar.

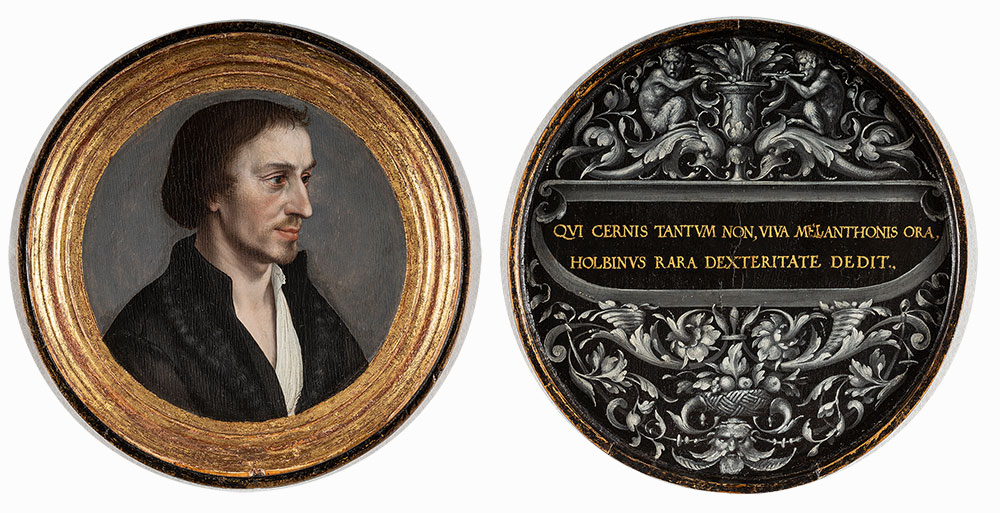

Philip Melanchthon

This portrait of Philip Melanchthon (1497–1560), the famous Protestant reformer, recalls the images of erudite men that Holbein painted during his years in Basel. Holbein never met Melanchthon and probably relied on a print as the basis for the likeness. This is the only known complete kapselbild (portrait with a lid) by the artist, and its inscription asserts that Holbein’s art rivals nature, a well-known theme from antiquity that would have appealed to Melanchthon as well as to the recipient of this object. Given its elaborate decoration and sophisticated theme, the piece may have been intended as a gift for someone of high status, perhaps even King Henry VIII of England.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Philip Melanchthon, ca. 1535

Oil on panel, with lid

Inscribed inside the lid, in Latin: Behold Melanchthon’s features, almost as if alive: Holbein has captured them, with the utmost skill.

Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover; PAM 798

Niedersachsisches Landesmuseum, Hannover

Portrait of an English Lady

This likeness conveys the poise of a woman of distinction, probably a member of the English court. The sitter’s serene features are balanced by the emphatic yet decorous gesture of her clasped hands. Holbein’s sumptuous palette and use of gold—on her fashionable French hood, the gleaming jeweled medallion affixed to her gown, and even the tiny pin fastening her black sleeve— date this portrait to the last years of his career but provide no clues to the sitter’s identity. The medallion, which shows two figures standing on either side of a fire, might represent an Old Testament scene.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Portrait of an English Lady, ca. 1540–43

Oil on panel

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Gemäldegalerie; 847

KHM-Museumsverband

Canones horopteri

This is the only known manuscript illumination by Holbein. The animal and foliate forms of the letter E recall his designs for woodcut letters as well as for jewelry and metalwork. The illumination decorates the beginning of a manual for using an astronomical instrument (the horopterum) to determine the times of sunrise and sunset. The author was the royal astronomer Nicholas Kratzer, whose portrait Holbein painted in 1528 (now at the Louvre, Paris). Kratzer dedicated this manuscript to King Henry VIII, who was keenly interested in scientific pursuits, and likely presented it to the king as a New Year’s gift.

Nicholas Kratzer (1487–1550)

Canones horopteri, 1528–29

Written by Pieter Meghen (1466/67–1540)

Illuminated by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Manuscript on parchment

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; MS. Bodl. 504, fol. 1r

Tantalus

This assured drawing, tinted with watercolor and touches of gold to guide the application of enamel by a goldsmith, is one of Holbein’s most finished designs for a hat badge or medallion. It focuses on the tale of Tantalus, who, according to Greek mythology, was eternally punished by Zeus for abusing the hospitality of the gods. Trapped in a pool beneath an apple tree, Tantalus (the source of the word “tantalize”) strains upward yet cannot reach the fruit to satisfy his hunger. Although he is in undulating water, Tantalus also is not allowed to quench his thirst. Despite its minute scale, the complex composition fully conveys the drama of the story.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Tantalus, 1535–40

Pen and black ink and watercolor, heightened in gold

Inscribed on the scroll, at top: Tantalus

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 1998; 1998.18.1

According to surviving inventories, Henry VIII and his courtiers owned large amounts of precious metalwork. These included medallions, hat badges, rings and other jewels made of silver, gold and enamel. As you move through this final room, you will notice that such intricate, elegant objects feature prominently in Holbein’s English portraits, adorning the woman from the Cromwell family in the picture from the Toledo Museum of Art and the unknown English Lady in the panel from Vienna.

This drawing is one of Holbein’s most finished compositions for a hat badge or medallion. Like many of the artist’s jewel designs, it features a story from classical mythology. Tantalus, who abused the hospitality of the gods, is punished by Zeus for his greed and doomed to be forever hungry and thirsty. Such an object might have been commissioned and worn by a wealthy individual as an expression of his or her taste and erudition, or a visual satire: a lavish jewel warning against excess.

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

William Parr, Marquess of Northampton

William Parr (1513–1571) was the brother of Catherine Parr, the sixth and final wife of King Henry VIII. Renowned for his taste and good looks, Parr is shown wearing a fur-edged gown made of white and purple velvet and satin (as indicated by the artist’s inscriptions). Also included are quick sketches showing details of various jewels that he supposedly wore. The object at upper left probably depicts St. George and the Dragon, likely a reference to George as a patron saint of the chivalric Order of the Garter, to which Parr belonged. Below, Holbein included a study of a jewel inscribed with the word MORS (death), probably part of a longer motto or device.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

William Parr, Marquess of Northampton, 1538–42

Black and colored chalks, white opaque watercolor, pen and black ink, and brush and ink on pink prepared paper

Inscribed, in German: wis felbet (white velvet), burpor felbet (purple velvet), wis satin (white satin), w (for weiss [white]) five times, Gl (gold) twice, gros (size), and MORS (death)

Lent by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II; RCIN 912231

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Hercules Pendant

A large pearl represents the muscled physique of the mythological strongman Hercules. He wears the skin of the Nemean lion, killed in the first of his twelve labors, and hoists one of the pillars of Cádiz from his tenth trial. In the 1500s, the figure of Hercules represented the virtue of fortitude and was the personal symbol of the French king Francis I, who may have commissioned this magnificent pendant.

Unknown maker, French

Hercules Pendant, ca. 1540

Gold, enamel (white, blue, and black), and a baroque pearl

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; 85.SE.237

Hat Badge Representing Prudence

One of the most popular types of jewels at the English court, the hat badge signaled the taste, wealth, and virtue of its owner. Such pieces could be attached to the brim of a hat with a pin or by stitching through metal loops at the top and bottom. In this work, Prudence, personified by a young woman in ancient Roman dress, regards herself in a mirror—reflecting on the true nature of her character and actions.

Unknown maker, French

Hat Badge Representing Prudence, 1550–60

Gold, enamel (white, blue, red, and black), chalcedony, and glass in the form of a table-cut diamond

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; 85.SE.238

Hat Badge with the Sacrifice of Isaac

This exceptionally large and elaborate hat badge portrays the dramatic climax of a story from the book of Genesis, when an angel stops Abraham as he is about to prove his faith by sacrificing his son Isaac. The high relief of the figures, clever incorporation of gemstones to relay the narrative, and vibrant enamel distinguish this example of exquisite small-scale sculpture

Unknown maker, French

Hat Badge with the Sacrifice of Isaac, ca. 1540–50

Gold, enamel, and jewels

The Al Thani Collection

© The Al Thani Collection 2022. All rights reserved.

Photography by Guillaume Benoit.

Hat Badge with the Head of St. John the Baptist on a Platter

Hat badges incorporated a range of religious and emblematic imagery in a small format. The severed head of St. John the Baptist on a bloody platter was a popular devotional image that related to faith while warning against jealousy and envy. This exceptional example, in which the head of the saint appears in high relief against shimmering red enamel, attests to the vividness and refinement of French jewels.

Unknown maker, French

Hat Badge with the Head of St. John the Baptist on a Platter, ca. 1500–1525

Gold, cast and enameled

Inscribed on the border, in Latin: Among those born of women, none has grown [greater than John the Baptist]

Victoria and Albert Museum, London; 473-1873

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Hat Badge with a Roman Warrior

Depicting the bust of an ancient Roman warrior in a niche, this badge resembles the decoration on prominent new buildings of the day, such as Henry VIII’s palace at Hampton Court, completed in the 1520s. This small-scale sculpture was probably originally enameled, similar to the badge of St. John the Baptist on view nearby, which would have made it more conspicuous and underscored its three-dimensionality. The portrait of Richard Southwell includes an enamelled hat badge of similar form to this example.

Unknown maker, English

Hat Badge with a Roman Warrior, Possibly an Emperor, ca. 1530–40

Gold, embossed and chased

Victoria and Albert Museum, London; 630-1884

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Richard Southwell

Sir Richard Southwell (1502/3–1564) rose to prominence in the last decade of Henry VIII’s reign. During this tumultuous period, which started with the rupture between the English sovereign and the papacy, the court was purged of those deemed insufficiently loyal to the king. Southwell played an important role in the trials of Sir Thomas More and, later, Henry Howard, both of whom were charged with treason and executed. Southwell’s portrait, by contrast, underscores his allegiance to Henry VIII. For instance, the inscription on the background refers to the regnal year rather than the calendar year. The fashionable hat badge, in the form of a female bust, also ties Southwell to the culture of luxury and erudition that characterized the Henrician court.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Richard Southwell, 1536

Oil on panel

Inscribed on background, in Latin: 10 July the year / H[enry] VIII 28 / At the age of 33

Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence; 1890

In 1536 Holbein was appointed as the royal painter to Henry VIII. Almost immediately, Holbein was inundated with new commissions for drawn and painted portraits, including this one for one of Henry’s new favored courtiers, Richard Southwell. Southwell was a witness at the trial of Sir Thomas More and responsible for removing More’s books from his cell in the Tower of London. Holbein never shied away from a completely naturalistic rendering of his sitter’s physical appearance, and in fact, his paintings were prized for this very aspect of realism. The scar on Southwell’s chin reflects Holbein’s careful representation of his sitter. In the preparatory drawing for the portrait, Holbein so deftly rendered Southwell’s scar that it was once thought to be damage to the paper support itself rather than part of Holbein’s portrayal.

Although Holbein does not present a very grandiose or overbearing image of Southwell, the prominent badge on his hat highlights Southwell’s aspiring social and court position. As shown throughout the exhibition, such jewels indicated the sitter’s erudition and fashionable taste, or their desire to be perceived as such. In the jewelry display cases behind you, there is a hat badge with a representation of a Roman man very similar in format to the badge on Southwell’s hat.

Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi

Designs for Medallions

Holbein’s ingenious designs for emblems and heraldry attest to his skill and to the popularity of such articles in Tudor England. Two drawings at top, likely intended as plans for precious objects, show a hand emerging from the clouds and resting on a closed book. Both feature the same motto in Italian: “I desire to observe that which I have sworn.” The circular format and Italian inscriptions connect these miniature compositions with Holbein’s painted An Allegory of Passion, thus revealing the artist’s ability to convey related ideas in a variety of scales and mediums. Designs for Holbein’s own heraldic arms, featuring a bull’s head, are included at the center of the mount.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Designs for Medallions, ca. 1532–43

Pen and black ink and wash; silhouetted

The British Museum, London, bequeathed by Sir Hans Sloane in 1753; SL,5308.22, SL,5308.44, SL,5308.34, SL,5308.154, SL,5308.42, SL,5308.164, SL,5308.28, SL,5308.40, SL,5308.15, SL,5308.19, SL,5308.13

Designs for Medallions

Now trimmed and mounted as small individual drawings, these studies for jeweled pendants and other types of metalwork were likely part of a sketchbook of Holbein’s designs known as the “Jewelry Book.” Lot and His Wife is the only surviving design for a jewel that also appears in one of Holbein’s paintings—Portrait of a Woman, Possibly from the Cromwell Family. It remains unclear, however, whether the artist designed the medallion himself or if this sketch records an object already owned by the sitter. It is equally possible that the jewel is an imaginary piece, invented by Holbein to embellish the portrait and its subject.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Designs for Medallions, ca. 1532–40

Pen and black ink and wash; silhouetted

The British Museum, London, bequeathed by Sir Hans Sloane in 1753; SL,5308.51, SL,5308.17, SL,5308.142, SL,5308.2, SL,5308.25, SL,5308.76, SL,5308.53, SL,5308.68, SL,5308.52, SL,5308.153, SL,5308.75, SL,5308.155, SL,5308.55

Portrait of a Woman

This woman’s embroidered cuffs and the gold decorations along her sleeves and headdress attest to her high status and likely association with the court. The portrait’s early history links it to the family of Thomas Cromwell, chancellor to King Henry VIII, and suggests that the sitter might have been a member of that prominent clan. Her intricate medallion depicts the biblical story of Lot and his wife in minute scale: An angel leads the pair away from the destruction of Sodom and tells them not to look back. Lot’s wife disregards the warning and is turned into a pillar of salt— represented here by a large rectangular gem at the center of the jewel. The medallion corresponds with the drawn design by Holbein on view nearby.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Portrait of a Woman, Possibly from the Cromwell Family, ca. 1535–40

Oil on panel

Inscribed on the background, in Latin: At the age of 21

Toledo Museum of Art, gift of Edward Drummond Libbey; 1926.57

Designs for Metalwork

These minute designs were intended for fabrication by goldsmiths and jewelers, who incorporated the intricate forms into the borders and clasps of their products. The drawings demonstrate Holbein’s refined technique, particularly his command of arabesques. The artist used similar forms to decorate the corners of his painting An Allegory of Passion.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Designs for Metalwork, ca. 1532–43

Pen and black ink and wash; silhouetted

The British Museum, London, bequeathed by Sir Hans Sloane in 1753; SL,5308.139, SL,5308.138, SL,5308.165, SL,5308.140, SL,5308.141, SL,5308.118, SL,5308.121, SL,5308.143

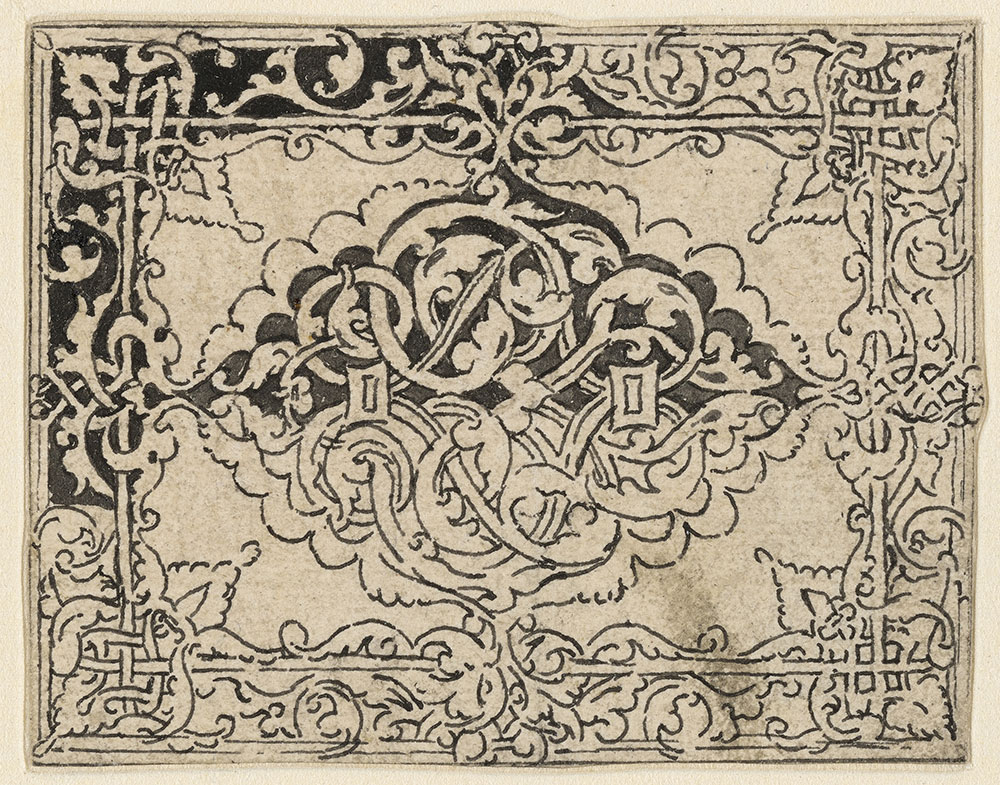

Designs for Metalwork

These designs for book-jewels were intended to be fashioned in gold and black enamel. The two on the top row feature rings that could be attached to a girdle, chain, or necklace. These metalwork covers also bear the initials of Thomas Wyatt the Younger (TW) and his wife, Joan (IW), which have been incorporated into fluid arabesques, a style fashionable in the English court in the period. The decorative patterns on these and other book-jewels were derived from ornamental motifs found on bookbindings.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Designs for Metalwork, ca. 1532–43

Pen and black ink with wash; silhouetted

The British Museum, London, bequeathed by Sir Hans Sloane in 1753; SL,5308.8, SL,5308.10, SL,5308.1, SL,5308.5

Calf leather binding

The binding of this devotional book is tooled in gold in a popular style of foliate ornament. First seen in Islamic manuscripts and artwork, this type of arabesque spread north into Europe through Italy and Spain, where it was used across an array of decorative arts. Reflecting the demand for such motifs, Holbein designed miniature book covers to be fabricated in gold and enamel as precious versions of gold-and-leather bindings. This example by an unknown artisan incorporates the name of the female patron for whom it was made.

Bound for Agnes Polus

Unknown binder

Calf leather, with gilt tooling on:

Heures à l’usage de Romme (Hours for the use of Rome)

Paris, ca. 1517

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907; PML 1063

Islamic-inspired foliate ornament, known as the arabesque, was a common decorative motif in early 16th century Europe. It was especially popular among the Italian humanists, as well as those wishing to emulate humanist aesthetics. As the decorative style spread, it became a graphic emblem for erudition and literary acumen.

The French bookbinding on display is only one example of the Renaissance taste for this foliate ornament. At the center of the gold-tooled composition is a pair of intersecting lines, enclosed above and below by a three-petaled leaf motif. This same core design is also visible in the book-jewel study Holbein produced for Thomas Wyatt the Younger and his wife Jane, on the wall above. Each example includes the owners’ name—a detail that would have been highly unusual a few decades before, which underscores the era’s new emphasis on the individual. Although Agnes Polus, whose name appears on the cover, is yet to be identified, we can presume that she was an aristocratic or upper class woman who wanted her expensive prayer book bound to reflect the current popular style.

Sir Thomas Wyatt

Witty, inventive, and occasionally satirical, the poet Thomas Wyatt (ca. 1503–1542) exerted wide influence in cultured courtly circles. An important early translator of poems by Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), Wyatt introduced the Italian sonnet form to England. Holbein portrayed Wyatt not as a writer, with book and pen, but as a courtier, perhaps in recognition of his recent knighthood. The artist rendered Wyatt’s identifying feature, his luxuriant beard, with a combination of animated strokes of ink and black, brown, and yellow chalks.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Sir Thomas Wyatt, 1535–37

Black and colored chalks, and pen and black ink on pink prepared paper

Lent by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II; RCIN 912250

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

John Leland

Holbein’s commemorative portrait bust of Thomas Wyatt is accompanied by laudatory verses by John Leland, a royal antiquarian and Wyatt’s longtime friend. Wyatt appears in a roundel frame, with his characteristic full beard. He is bareheaded and wears a tunic in the manner of an ancient philosopher, in keeping with his own poetry and Leland’s verses. The lines above the portrait praise Holbein’s artistic mastery while acknowledging painting’s inability to represent a subject’s mind or spirit—a sentiment expressed in portraits of Erasmus that are also on view.

John Leland (1506?–1552)

Naeniae in mortem Thomae Viati equitis incomparabilis (Dirges on the death of the incomparable knight Thomas Wyatt)

Woodcut after a design by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

London: Reyner Wolfe, 1542

Text above woodcut, in Latin: On the image of Thomas Wyatt. Holbein, greatest in the shining art of painting, portrayed his image artistically, but no Apelles [i.e., painter] can portray the blessed genius and spirit of Wyatt.

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Fellows, 1969; PML 59326.5

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey

Henry Howard (1516/17–1547)—a poet, soldier, and protégé of Thomas Wyatt—was still a teenager when he posed for this forthright yet delicate portrait. Holbein paid close attention to the almost imperceptible irregularities of the young man’s features, such as the slightly different shapes of Howard’s brown eyes and eyelids. The artist shaded the right side of the sitter’s face with a combination of black and red chalks, which he carefully blended by rubbing or stumping to produce a sculptural effect.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, 1532–33

Black and colored chalks, and pen and black ink on pink prepared paper

Lent by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II; RCIN 912215

This study of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, is one of Holbein’s most subtle drawings. Using black chalk, the artist skillfully established the oval of the head and added subtle shading along its inner outline. Within this vertically elongated form, a thin, delicately varied pen and ink line separates the young man’s lips. Holbein carefully observed—or perhaps even enhanced—the natural asymmetry of the sitter’s features. If you look closely, you will notice clear discrepancies of size and placement in the rendering of Howard’s eyes, eyebrows, nostrils, and even ears.

Howard, who sat for this portrait in his late teens, was the first cousin of Anne Boleyn and a close childhood friend of Henry FitzRoy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII. His most enduring contributions, however, were in the field of poetry. In addition to writing sonnets, Howard was the first English writer to publish blank verse as part of his translation of Virgil’s Aeneid.

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Charles de Solier, Comte de Morette

Charles de Solier, Comte de Morette, (1480–1552) served as French ambassador to the court of Henry VIII on several occasions between 1526 and 1535. He commissioned this portrait medal to commemorate his illustrious career. The round format and high relief of Christoph Weiditz’s portrait bust help convey Morette’s imposing presence, with his square beard and fur-lined gown. Weiditz likely based Morette’s likeness on Holbein’s portrait of the diplomat, (illustrated at right) now part of the Dresden State Art Collections.

Christoph Weiditz the Elder (ca. 1500–1559)

Charles de Solier, Comte de Morette (obverse), 1530s

Boxwood

Inscribed around perimeter, in Latin: Charles de Solier, Lord of Morette at the age of 50

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Salting Bequest; A.507-1910

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

An Allegory of Passion

The central image of a rider astride a galloping horse embodies a lover’s quest for the heart of his beloved, as conveyed by the inscription below, taken from a work by the Italian poet Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374). Unique in Holbein’s oeuvre, the painting may have been a personal emblem or part of a series of images celebrating the theme of love. The foliate patterns are related to those Holbein used in his designs for decorative metalwork and on the book-jewel drawings for the Wyatt family. The unknown patron of the painting was likely an English courtier devoted to Petrarch’s poetry, perhaps Thomas Wyatt or Henry Howard.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

An Allegory of Passion, ca. 1532–36

Oil on panel

Inscribed on the cartouche, lower center, in Italian: And so desire carries me along (Petrarch, Il canzoniere, CXXV)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; 80.PB.72

An Allegory of Passion is a rather unusual composition in Holbein’s career, both in terms of its diamond-shaped format and its allegorical subject matter. In fact, this is the only allegorical panel painting in the artist’s entire oeuvre. The rider, dressed like a lover or poet, sits astride a swiftly galloping horse, which illustrates a line from Petrarch: “And so desire carries me along.” In the Renaissance, horses had multiple meanings, as symbols of speed, virtue, and passion. The combination of the image and text indicates that the original owner of the work may have had an interest in love poetry.

Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard both helped to popularize Petrarch’s poetry in Tudor England and developed the English sonnet—a poetic form that William Shakespeare would later immortalize. Either Wyatt or Howard, whose portraits are displayed nearby, may well have been the original owner of this Petrarchan allegory. The foliate decoration in the four corners is reminiscent of the metalwork designs Holbein produced, including the book-jewel design for Wyatt, on view nearby.

Recent scientific analysis of the painting has revealed layers of underdrawing and changes Holbein made to the composition, including altering the rider’s head from profile to the three-quarter position and changing the position of the horse’s legs. Some of the underdrawing may still be seen on the horse’s neck and highlighting the musculature of its legs.