Holbein’s Dance of Death

In the dance of death, an allegory common in medieval and Renaissance Europe, a skeleton “dances” with all members of society—from pope to peasant—as a reminder of their inevitable earthly demise. Depicted in church and cemetery murals as well as prayer-book illustrations, the motif was a positive and sympathetic prompt to prepare for a Christian death. This perspective on mortality relates such imagery to portraiture, which aimed to capture and preserve an individual’s likeness at a fleeting moment in time.

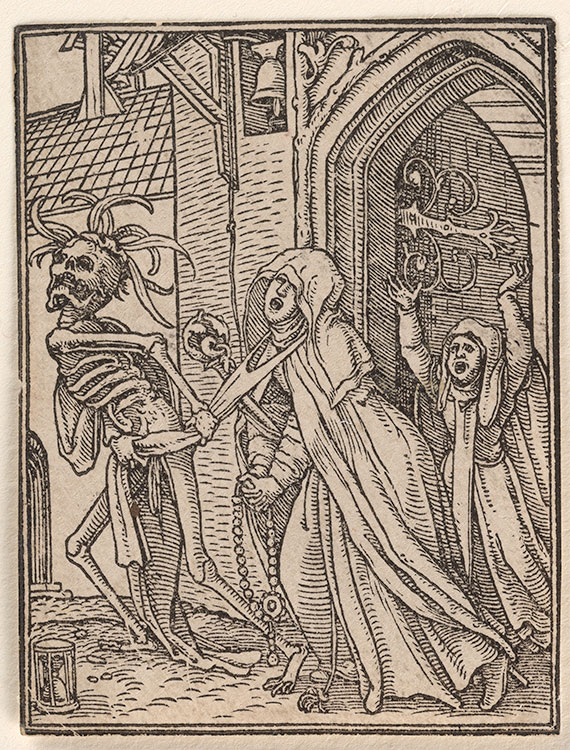

The creation of printed images was typically a collaboration between an artist who composed the illustrations and a blockcutter who transferred these drawings into a printable medium, such as woodcut. In the early 1520s, the Basel blockcutter Hans Lützelburger was commissioned to produce dance of death imagery for a new book, The Images of Death, and he turned to Holbein for the compositions. Holbein and Lützelburger’s designs transformed the traditional medieval series of stiff figures in two-dimensional settings into three-dimensional genre scenes full of allusions to contemporary life. As with his portraits, Holbein used specific emblems and objects to represent various members of society as Death leads them—passively, comically, or mockingly— in the dance.

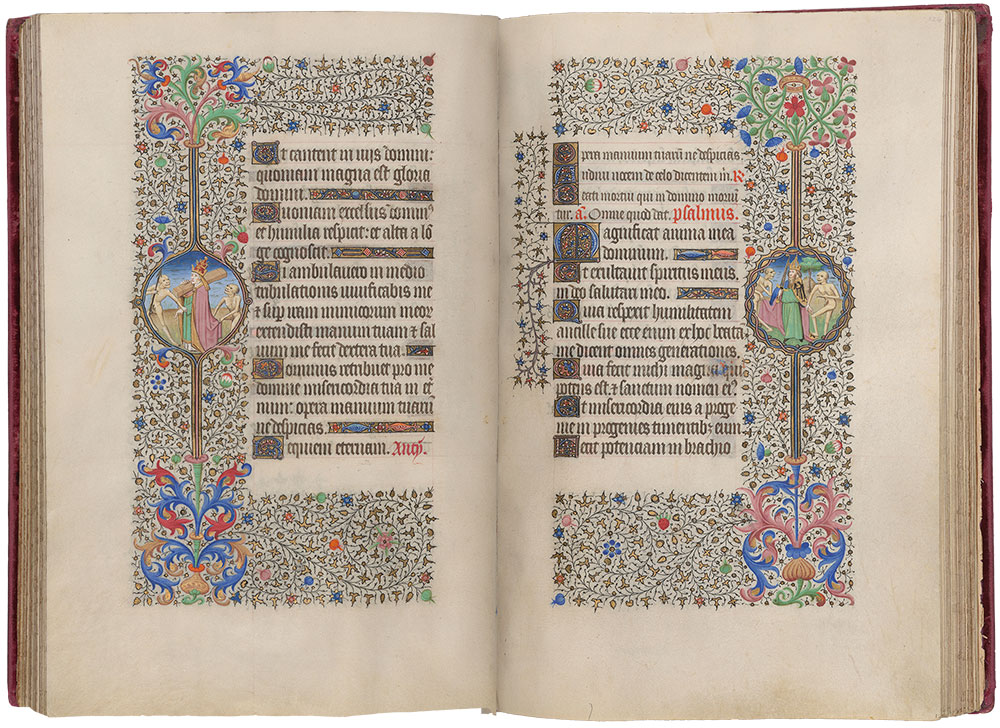

Book of Hours

Used as tools for devotion and preparing one’s soul for a Christian death, personal prayer books often featured dance of death imagery. The margins of this Book of Hours include fifty-six such scenes. The manuscript was produced in Paris, and the scenes are supposedly derived from the original dance of death mural, dating to 1424–25 (and destroyed in 1699), in the city’s Cemetery of the Holy Innocents. Here you can see the minuscule, simplistically rendered pope (left) and emperor (right). Unlike the Parisian mural, this dance of death excludes women, which might indicate that the original patron was male.

Book of Hours

Paris, 1430–35

Illuminated by Bedford Master and workshop (act. 1415–35)

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909; MS M.359, fols. 123v–124r

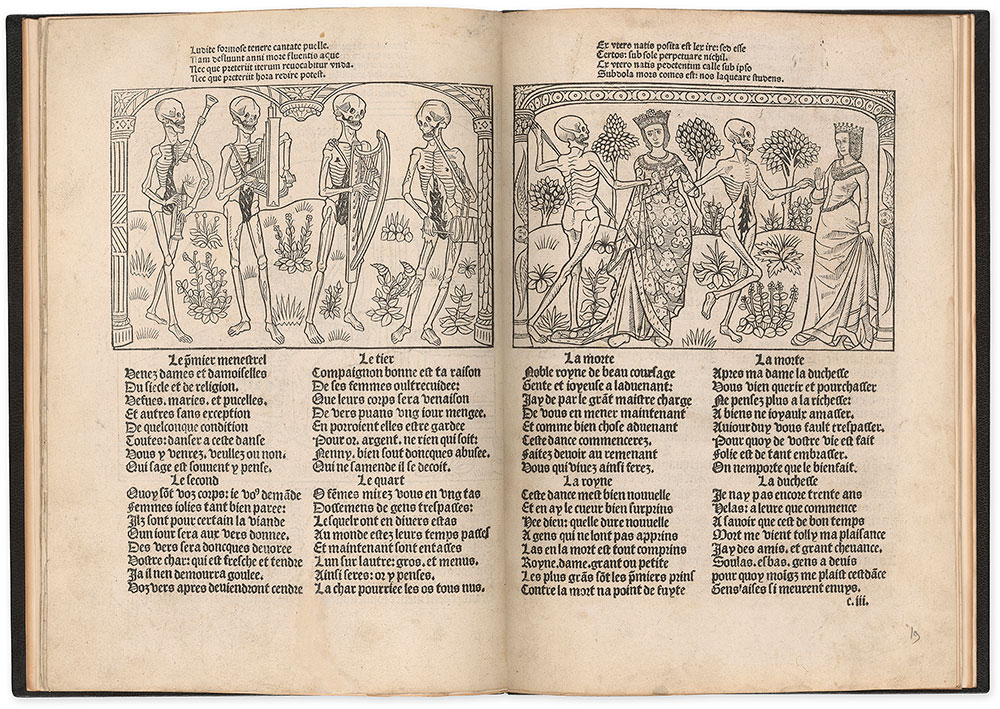

La danse macabre nouvelle

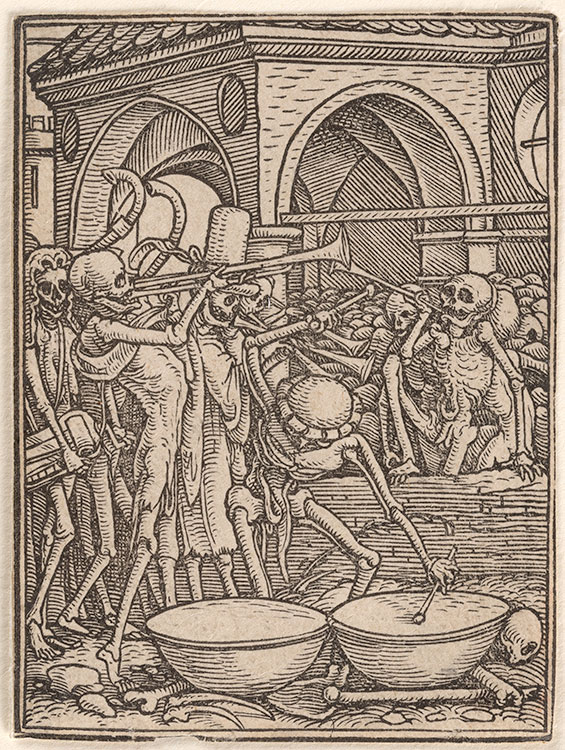

La danse macabre nouvelle, first printed in 1485 by Guy Marchant, is perhaps the closest reproduction of the Parisian cemetery mural in which dance of death imagery first appeared—most notably, the illustrations include the arcade from the architectural setting as a framing device. The text, also derived from the cemetery mural, is a dialogue wherein death indicates the inevitability of the dance while the protagonists variously bemoan their poorly spent lives and loss of material gain. The printed editions include a dance for men followed by a separate dance for women, each introduced with skeletons playing musical instruments. Produced four decades later, Holbein and Lützelburger’s illustrations would retain the skeletal musicians but intermingle men and women.

La danse macabre nouvelle (The new dance macabre)

Paris: Guy Marchant, 7 June and 7 July 1486

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1975; PML 75062

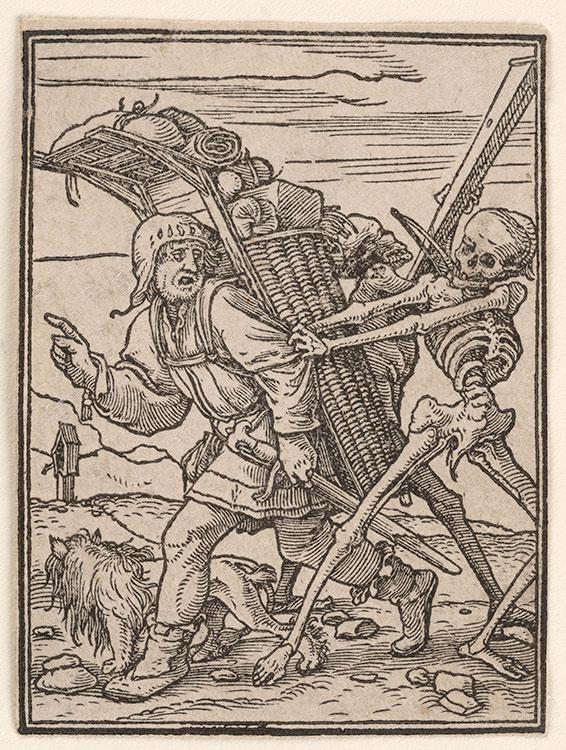

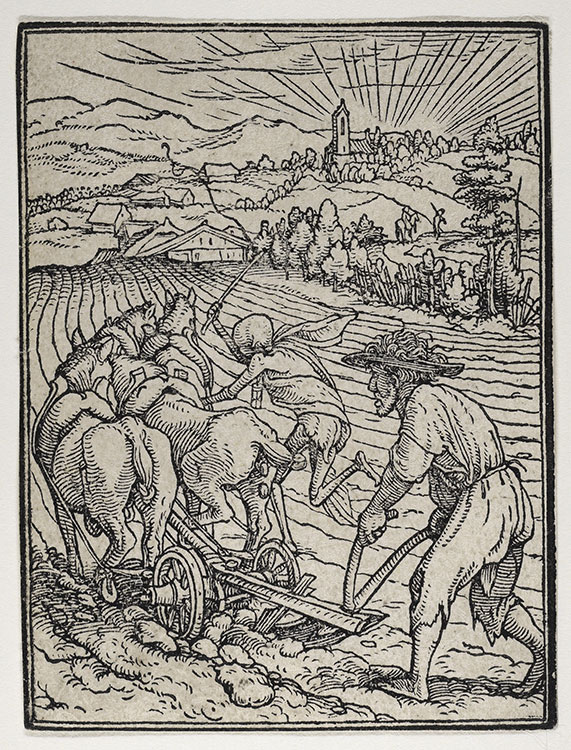

Book of Hours

Prior to his collaboration with Lützelburger on the prints for Images of Death, Holbein traveled to France, hoping to find employment at the royal court. In Tours, Holbein encountered a workshop of manuscript illuminators, whose illustrations for Books of Hours provided inspiration for at least two death scenes. Holbein converted the workshop’s illustrations of the month of October, featuring a laborer plowing a field (shown in this later manuscript), into Death and the Plowman (or Peasant) for the printed series. In Holbein’s reinterpretation, a rather pastoral scene of agrarian life takes a sinister turn as Death whips the horses onward: the plowman’s toil leads to his demise.

Book of Hours

France, probably Tours, ca. 1530–35

Illuminated by the Master of the Getty Epistles (act. 1528–50)

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911; MS M.452, fols. 10v–11r

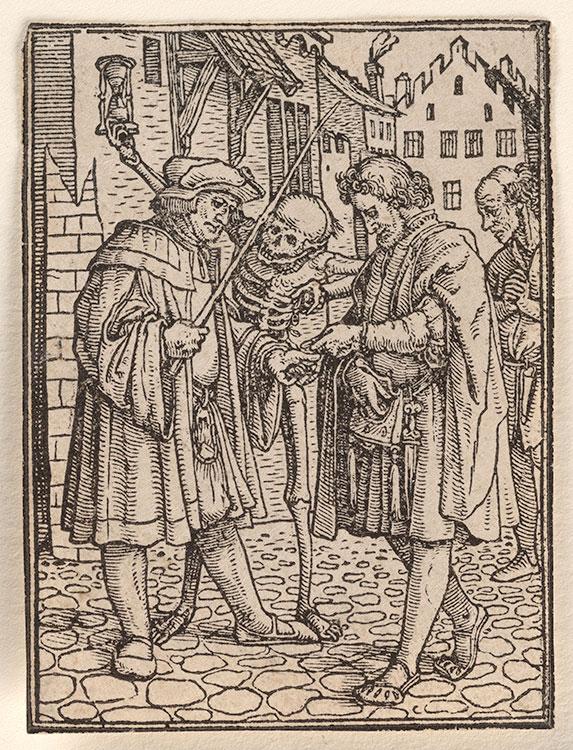

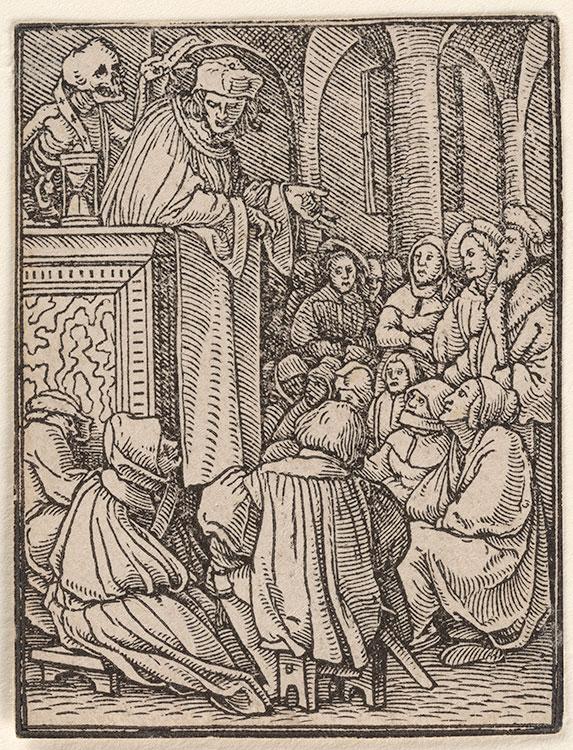

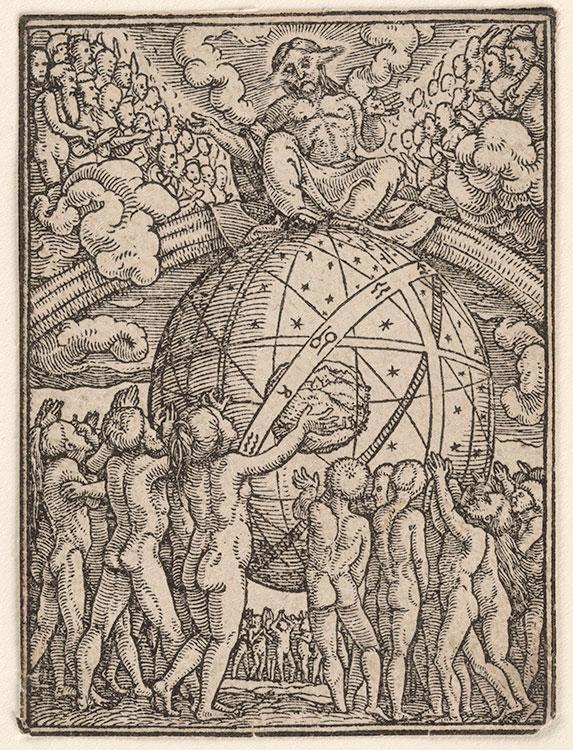

Images of Death

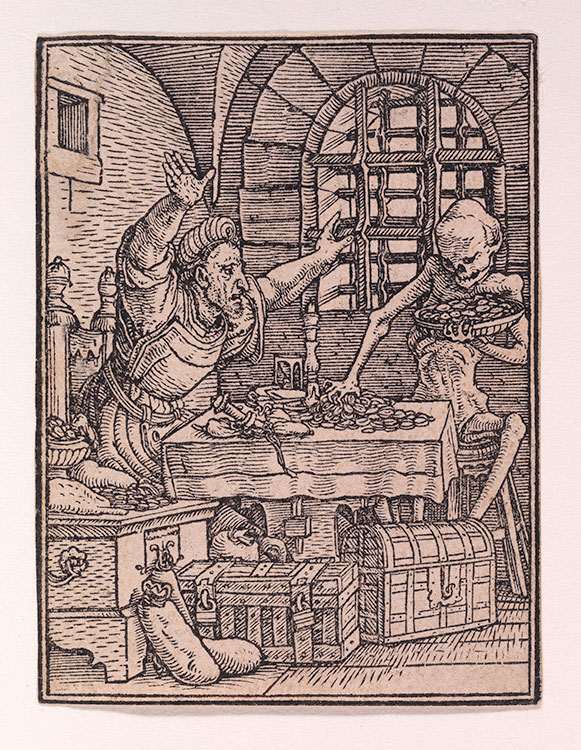

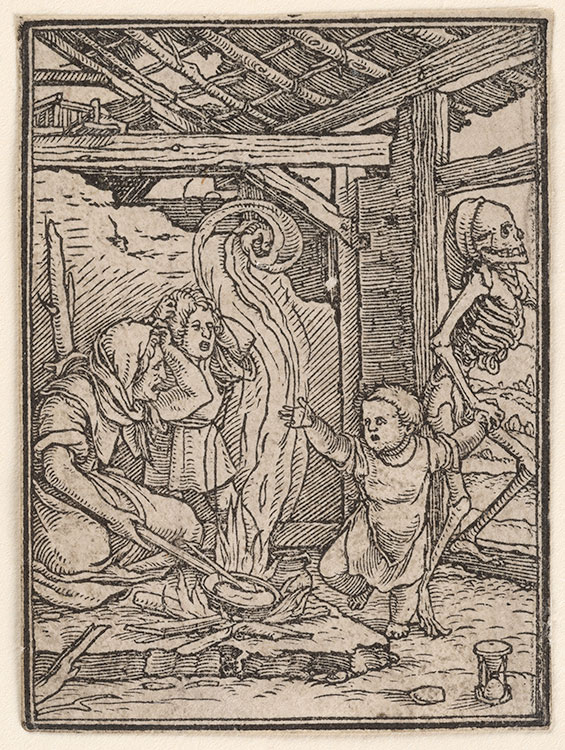

Lützelburger and Holbein reimagined the medieval dance of death into detailed genre scenes where Death catches people amid their daily routines. As in Holbein’s portraits, objects and emblems indicate individuals’ social strata or professions and in some cases mockingly aid in their demise. Lützelburger signed the bed frame in the image of the duchess (fourth frame [far right], top row, print five) with his initials, HL. Lützelburger was an exceptionally skilled blockcutter, more so than the other artists with whom Holbein had worked, and his abilities allowed for the best translation of Holbein’s compositions into print, especially at the small scale of this series.

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Images of Death, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.1–40

Contrary to what we might think today, during the Renaissance, the Dance of Death imagery was not considered morbid or scary. Rather, it served as a positive reminder to lead a good, devout life. While the earlier medieval tradition tended to represent the figures in the dance as rather unexpressive and static, Lützelburger and Holbein created a series full of action and high emotion, depicting the protagonists amid their daily routines.

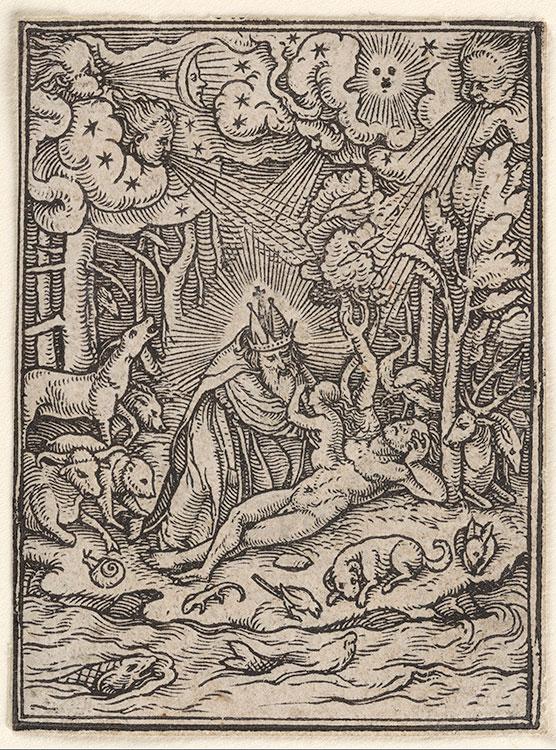

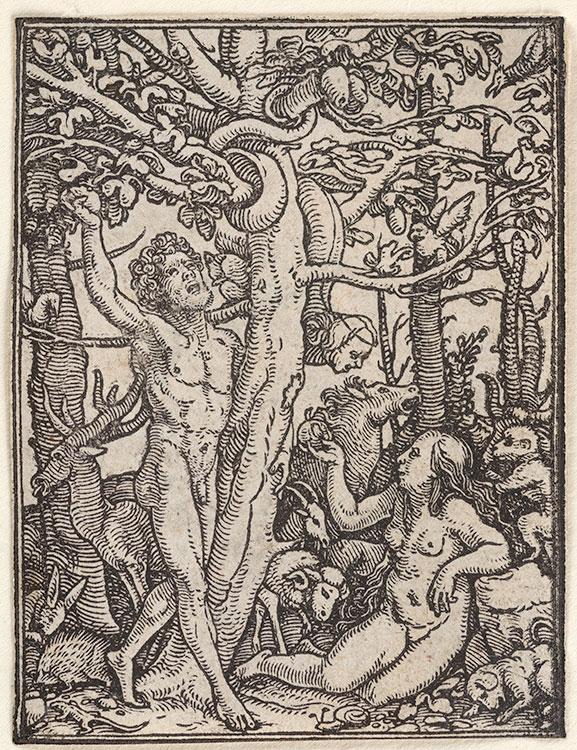

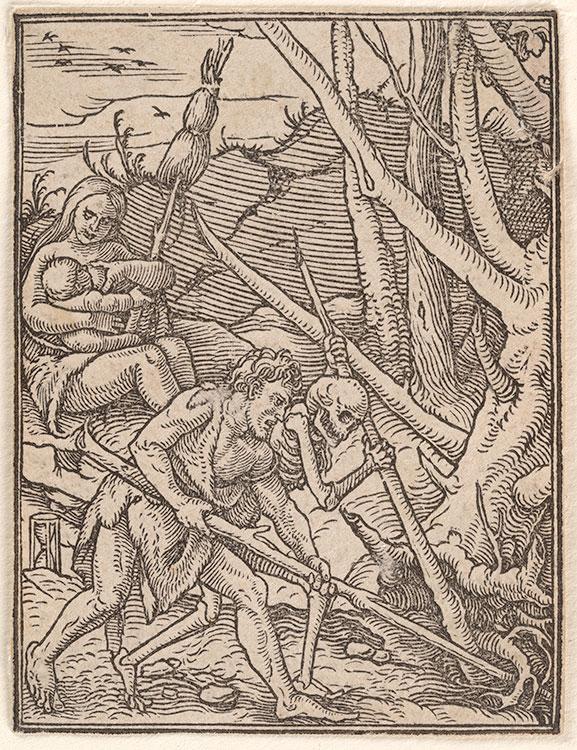

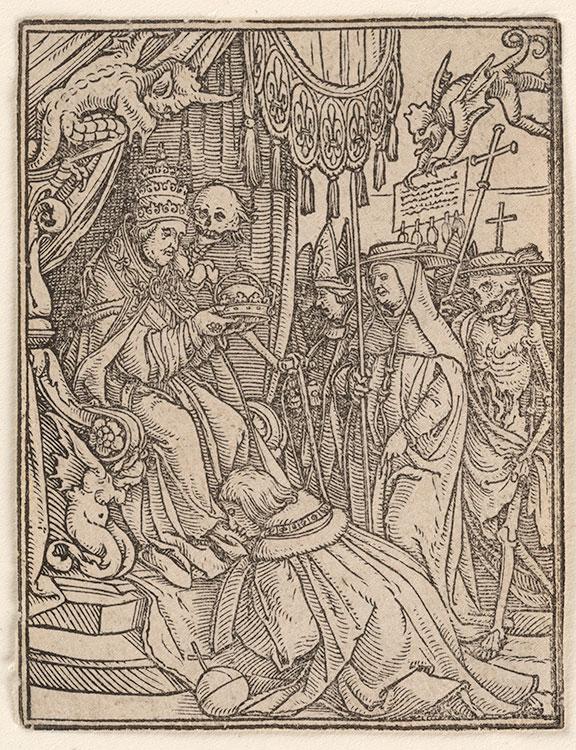

Death comes into the story of humanity after the Fall, when Adam and Eve are banished from the Garden of Eden. These events are narrated in the first four scenes. The successive thirty-six prints represent Death meeting members of every social class. Holbein varied the compositions for each figure and adapted the manner in which they met their fate. Some protagonists, like the Monk or Rich Man, scream and try to fight off Death. The Sailor, Knight, and Count all meet rather violent ends. Death seems to surprise the Nun meeting with her lover and the Bishop tending his flock. The Old Man and Old Woman are more passive in the acceptance of their awaited fates. Some scholars have found Protestant sympathies in the scenes, as with the demons who help the Pope to sell indulgences—a practice famously criticized by Martin Luther in the Ninety-five Theses.

This series is the masterpiece of both Holbein’s and Lützelburger’s print careers. In each other, the two artists found a collaborator of equal talent to their respective expertise: Holbein finally had a blockcutter who could expertly translate his drawings into relief print, and Lützelburger had a draftsman whose mastery of three-dimensionality could be translated into print by his extraordinary deftness of carving.

Creation of Eve

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Creation of Eve, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.1

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

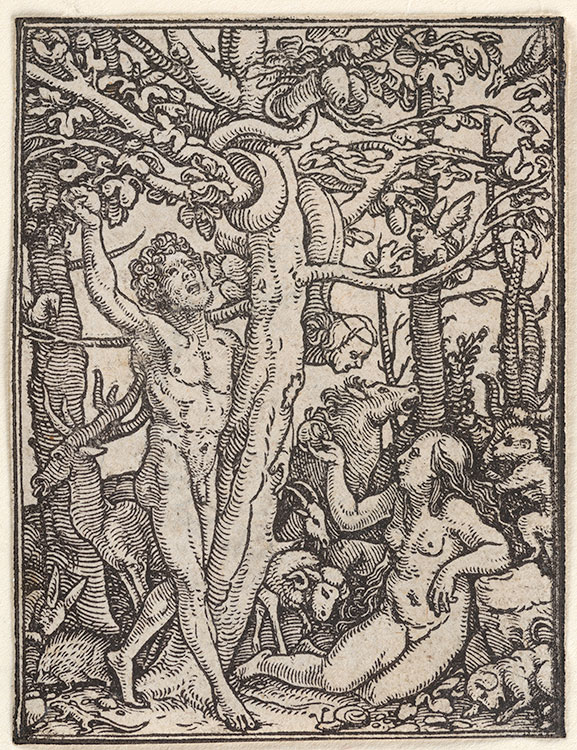

Fall (or Temptation of Adam)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Fall (or Temptation of Adam), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.2

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

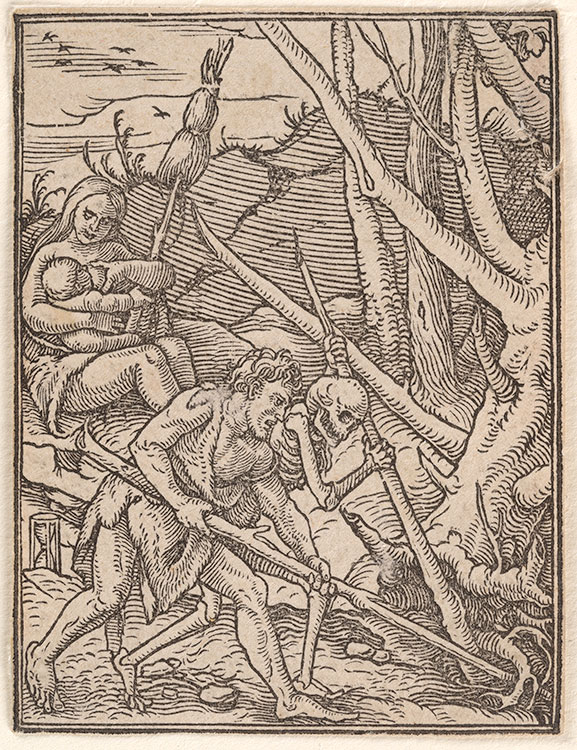

Expulsion from Paradise

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Expulsion from Paradise, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.3

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Adam Plowing

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Adam Plowing, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.4

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Skeletons Making Music (or the Cemetery)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Skeletons Making Music (or the Cemetery), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.5

Death and the Pope

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Pope, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.6

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Emperor

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Emperor, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.7

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

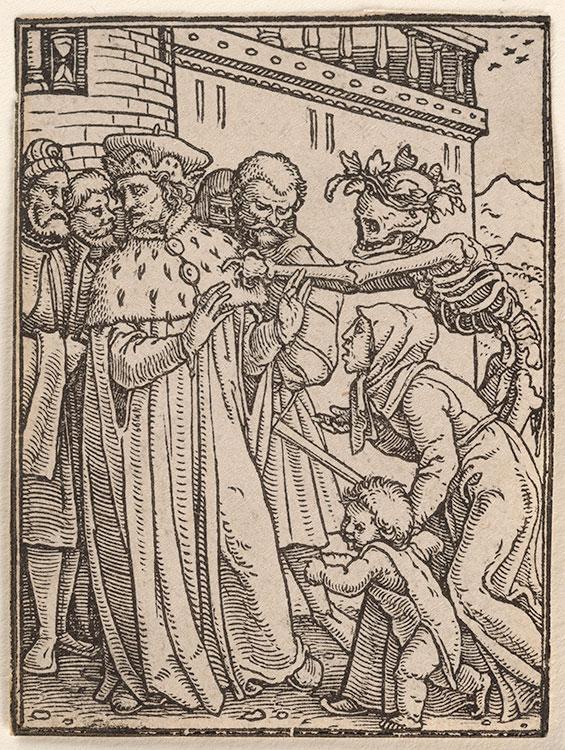

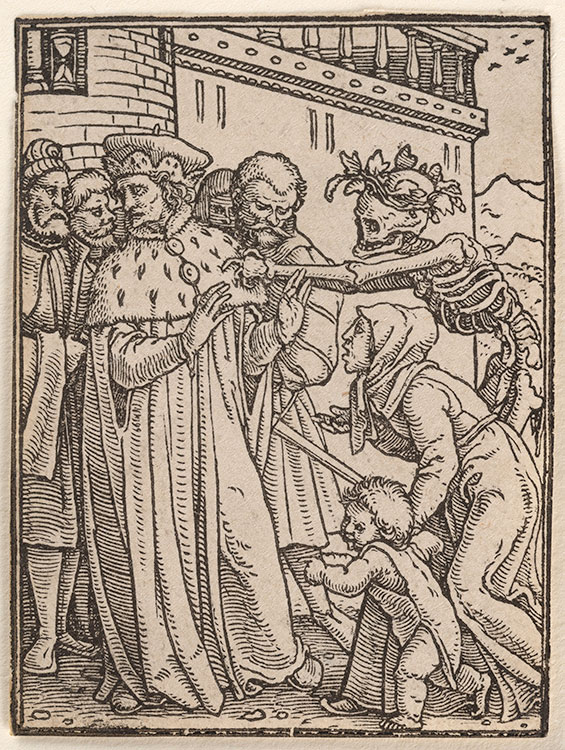

Death and the King

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the King, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.8

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Cardinal

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Cardinal, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.9

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Empress

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Empress, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.10

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Queen

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Queen, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.11

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Bishop

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Bishop, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.12

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Duke

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Duke, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.13

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Abbot

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Abbot, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.14

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

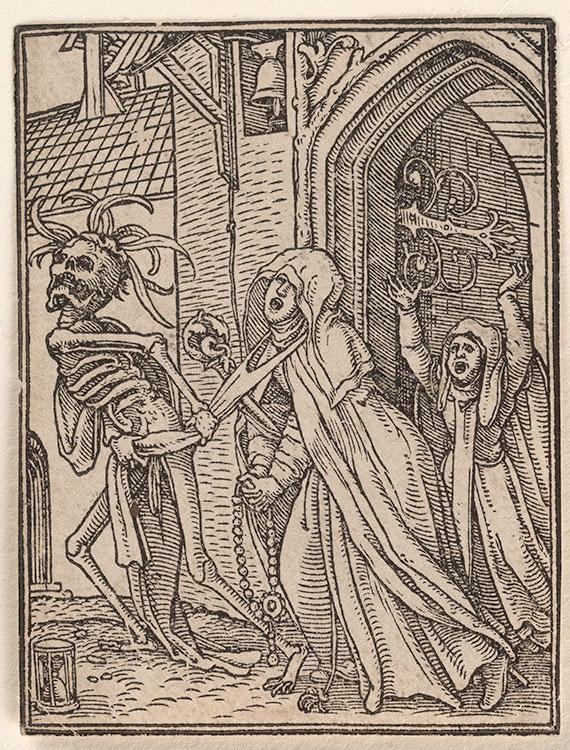

Death and the Abbess

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Abbess, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.15

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Dean (or Canon)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Dean (or Canon), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.16

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

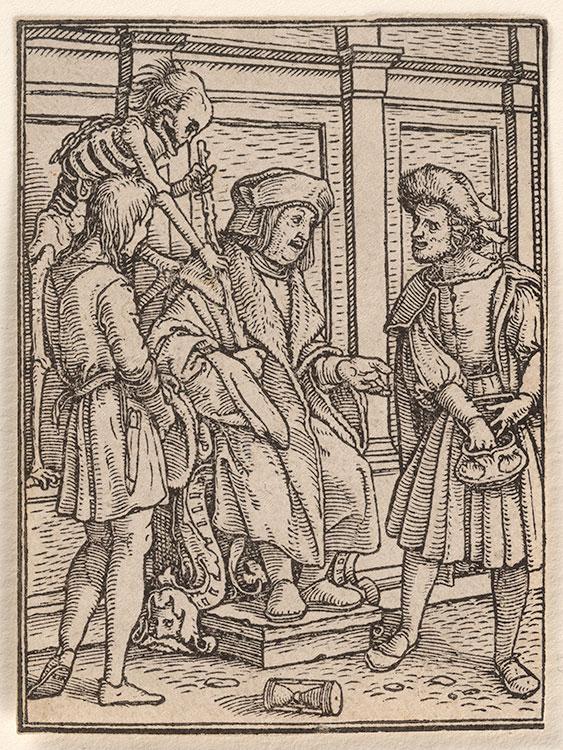

Death and the Judge

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Judge, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.1–40

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Nobleman

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Nobleman, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.18

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Lawyer (or Advocate)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Lawyer (or Advocate), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.19

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Councilor

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Councilor, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.20

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Clergyman

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Clergyman, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.21

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Priest (or Preacher)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Priest (or Preacher), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.22

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Monk (or Mendicant)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Monk (or Mendicant), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.23

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Nun

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Nun, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.24

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Old Woman

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Old Woman, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.25

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Doctor (or Physician)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Doctor (or Physician), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.26

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Rich Man

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Rich Man, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.27

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Merchant

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Merchant, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.28

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Skipper (or Sailor)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Skipper (or Sailor), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.29

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

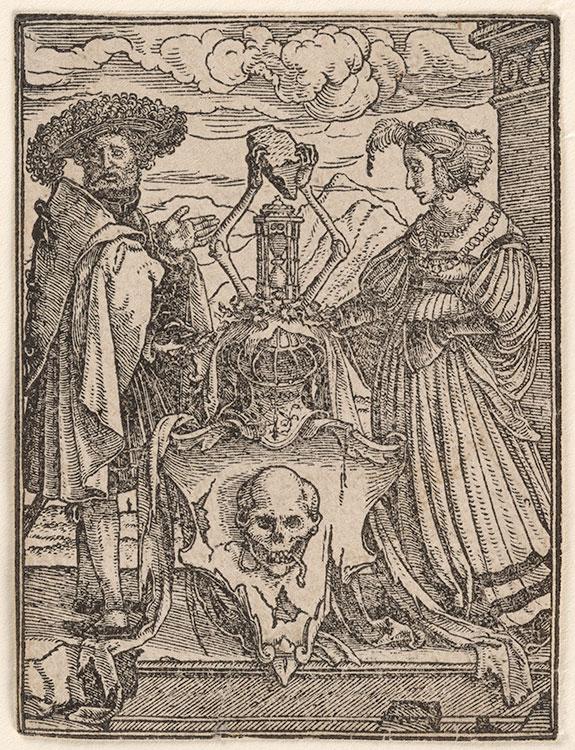

Coat of Arms of Death

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Coat of Arms of Death, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.40

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Child

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Child, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.38

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Count

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Count, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.31

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Countess

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Countess, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.33

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Duchess

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Duchess, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.35

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

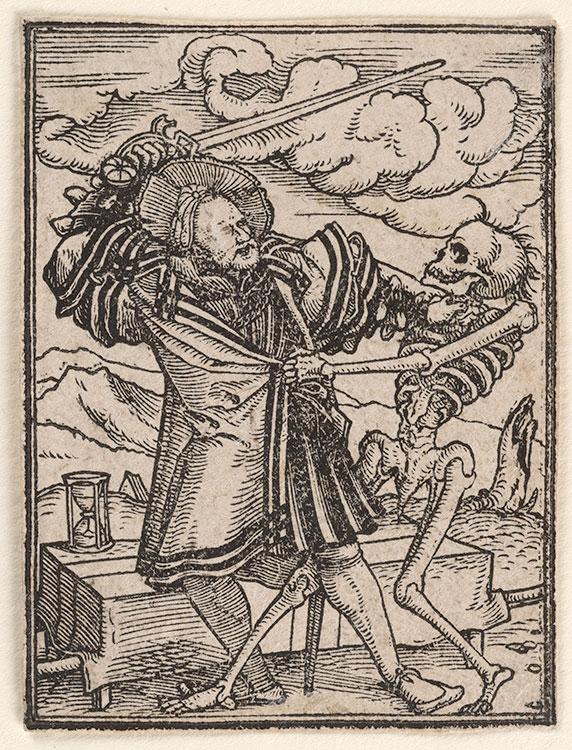

Death and the Knight

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Knight, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.30

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Noblewoman

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Noblewoman, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.34

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Old Man

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Old Man, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.32

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Plowman (or Peasant)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Plowman (or Peasant), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.37

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Shopkeeper (or Trader)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Shopkeeper (or Trader), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.36

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

The Last Judgment

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

The Last Judgment, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.39

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

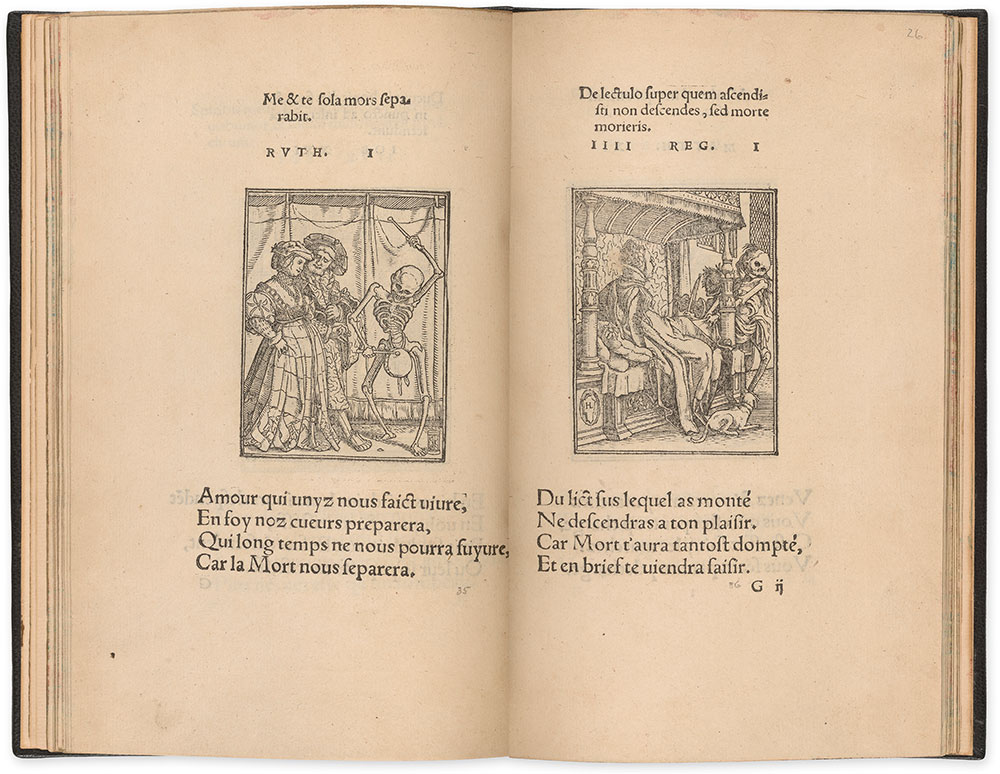

Les simulachres & historiees faces de la mort

Lützelburger and Holbein’s Images of Death series was always intended to illustrate a printed book. The devotional texts were written by the French poets Nicholas Bourbon (whose portrait by Holbein is also on view) and Jean de Vauzelles or Gilles Corrozet. The introduction states that several of the blocks were incomplete when Lützelburger died. The printers failed to find a blockcutter of equal ability to complete the images (ultimately hiring a less skilled artist), which is why the book was not published until 1538, twelve years after Lützelburger’s death. Nevertheless, the edition was hugely successful and reprinted in Lyon into the 1560s. Holbein’s compositions were copied by dozens of printers and artists across Europe into the nineteenth century.

Les simulachres & historiees faces de la mort (The simulated and illustrated faces of death)

Woodcuts by Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Lyon: Melchior and Gaspar Trechsel for Jean and François Frellon, 1538

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased with the De Forest collection, 1899; PML 2112

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan by 1905; PML 2113

Historiarum veteris instrumenti icones

.jpg)

While producing the Images of Death, Lützelburger and Holbein were also collaborating on a series of illustrations of the Old Testament for the same Lyon printers. Slightly larger than the death scenes, the Old Testament images often feature expansive landscapes reflecting the epic nature of the scriptural narratives. As with the Images of Death, the Old Testament woodblocks were unfinished at Lützelburger’s death; the project was completed by Veit Specklin prior to publication. The woodcuts were used to illustrate this small picture book and a Bible.

Historiarum veteris instrumenti icones ad vivum expressae (Icons of deeds of ancient history represented from life)

Woodcuts by Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526) and Veit Specklin (d. 1550), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Lyon: Melchior and Gaspar Trechsel for Jean and François Frellon, 1538

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased with the De Forest collection, 1899; PML 2126

Latin Capital Letter Alphabet (Death Alphabet)

Prior to the Images of Death, Holbein designed a Latin alphabet for Lützelburger that showcased the latter’s dexterity at woodcutting. The minuscule compositions expertly render action, emotion, and three-dimensionality—qualities that the other blockcutters who worked with Holbein could not as effectively achieve. The capital letters were intended to be used in a printed book to begin a paragraph or section of text (what is often called a “drop cap” today). This print was produced as an advertisement for Lützelburger, however, and the letters themselves appeared only in a few books published in Basel during the 1520s and ’30s.

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Latin Capital Letter Alphabet (Death Alphabet), ca. 1523

Woodcut

Inscribed at bottom center, in German: Hans Lützelburger, blockcutter, called Franc [i.e., of French origin]

Kunstmuseum Basel, Kupferstichkabinett, X.228

Battle of the Naked Men and Peasants

Lützelburger had been a blockcutter in Augsburg on several print projects for Emperor Maximilian I. After the Holy Roman emperor’s death in 1519, the imperial workshop closed, and Lützelburger moved to Basel in search of work. Prior to his collaboration with Holbein on the Death Alphabet, Lützelburger produced this sheet (in either Augsburg or Basel) as an advertisement of his abilities engraving the human form, landscape, and text. Lützelburger prominently displayed his name and role (formschneider, meaning “blockcutter”) on the print, while the artist responsible for the design, Hogenberg, is represented with his initials, HN, at the bottom-left corner of the figural composition.

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after a design by Nikolaus Hogenberg (1500–1539)

Battle of the Naked Men and Peasants, 1522

Woodcut

Inscribed at bottom left, in German: Hans Lützelburger, blockcutter, 1522

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Ruth and Jacob Kainen Memorial Acquisition Fund; 2017.21.1

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington