A Teacher and Mentor

Brooks was highly invested in the education of younger generations, treating seriously the talents and issues of young people and teaching them how to use writing to navigate a difficult and discriminatory world. This focuses on Brooks’s impact as a teacher and mentor to younger writers throughout her career. Her dedication to youth education was obvious in her material and personal contributions to her students and mentees. Her commitment to the education of young people was multileveled and involved deep conversations about vulnerability and self-expression.

Brooks was highly invested in the education of younger generations, treating seriously the talents and issues of young people and teaching them how to use writing to navigate a difficult and discriminatory world. This focuses on Brooks’s impact as a teacher and mentor to younger writers throughout her career. Her dedication to youth education was obvious in her material and personal contributions to her students and mentees. Her commitment to the education of young people was multileveled and involved deep conversations about vulnerability and self-expression.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

To Disembark (Chicago: Third World Press, 1981)

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198569

Reprinted By Consent of Brooks Permissions

To Disembark

Witnessing the ongoing violence affecting young people in her neighborhood—exemplified by this poem, “A Boy Died in My Alley”—Brooks started working with local youth. In 1970, alongside playwright Oscar Brown Jr. and poet-organizer Walter Bradford, her lifelong friend, Brooks began teaching creative writing to members of the Blackstone Rangers, a local gang composed mostly of teenagers and young adults. The Rangers had no interest in reading the classics or learning iambic pentameter, and they challenged Brooks to become more imaginative in her lessons. Brooks rose to the task and soon became not only a teacher but also a mentor and friend to the youths. She would go on to write poems in sympathy and solidarity with the young Rangers’ hopes and struggles.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

“A Boy Died in My Alley”

In To Disembark (Chicago: Third World Press, 1981)

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198569

Reprinted By Consent of Brooks Permissions

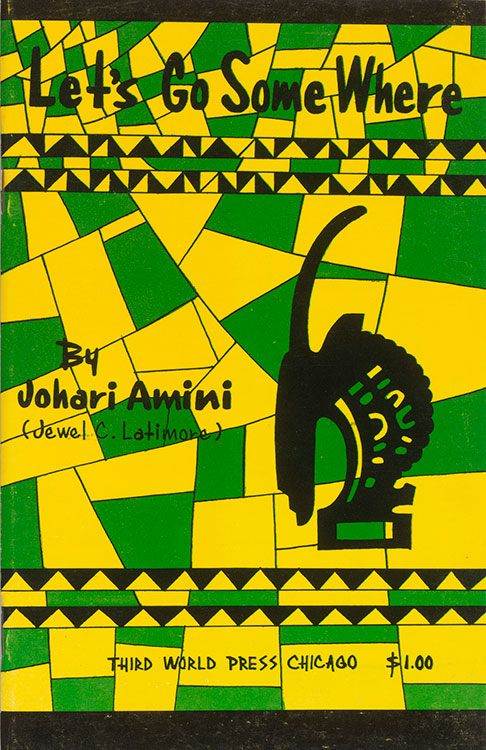

Let’s Go Some Where

Three members of Brooks’s writing workshop—Johari Amini, Don L. Lee (a.k.a. Haki R. Madhubuti), and Carolyn Rogers—established their own publishing company, Third World Press, in December 1967. The press began in Madhubuti’s basement apartment on the South Side of Chicago with four hundred dollars, a used mimeograph machine, and a commitment to publishing texts by writers involved in the Black Arts movement. It has since grown to become one of the most formidable Black publishing houses in the United States. Brooks would release five books, including her second memoir, Report from Part Two (1996), with Third World Press, working closely with her former mentees.

Johari Amini (b. 1935)

Let’s Go Some Where

Introduction by Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Chicago: Third World Press, 1973

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2021; PML 198722

Reproduced with the permission of Omar Lama

Don L. Lee (b. 1942; a.k.a. Haki R. Madhubuti)

Don’t Cry, Scream

Introduction by Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1969

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198581

© Broadside Lotus Press

The Tiger Who Wore White Gloves, or, What You Are You Are

Brooks published a number of children’s books throughout her career, often using the medium to discuss topics such as acceptance and belonging. The mother of two children, Henry (born 1940) and Nora (born 1951), Brooks was frequently inspired by her experience as a parent to write about the trials and tribulations of childhood. Her books for young readers were extensions of the lessons that she shared with her son and daughter, bringing what she called the “privacy of family pleasure” to the world.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

The Tiger Who Wore White Gloves, or, What You Are You Are

Chicago: Third World Press, 1974

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198523

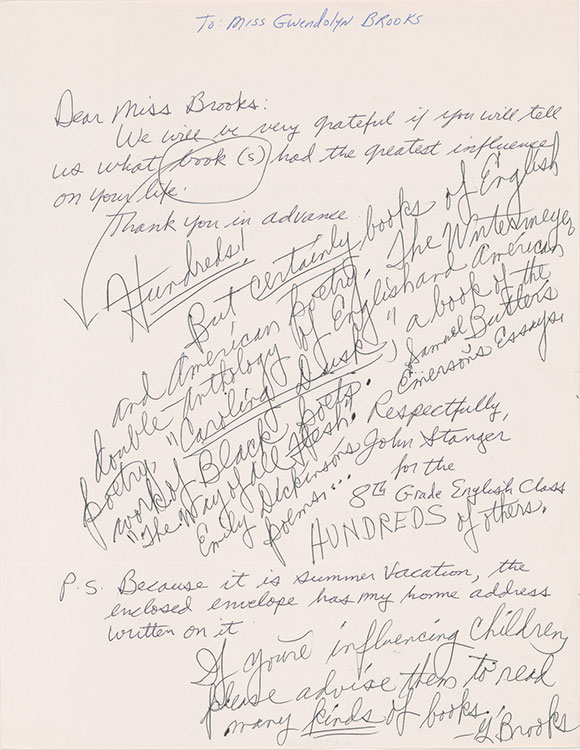

Letter to Gwendolyn Brooks

As a teacher, Brooks went above and beyond for her students, making sure they were exposed to many types of literature and purchasing them tickets to local poetry readings. As Brooks wrote in this letter to an eighth-grade teacher, “If you’re influencing children, you must encourage them to read many kinds of books.” Throughout her career, Brooks continued to support younger writers both financially and educationally.

John Stanger

Letter to Gwendolyn Brooks with Brooks’s response, 1990–92

Purchased on the Drue Heinz Fund for Twentieth-Century Literature, 2020; MA 23730.4

Reprinted By Consent of Brooks Permissions

Young Poet’s Primer

Inspired by her years of teaching and experience working with independent Black publishers, Brooks created her own imprint in 1980 and produced these guides for young poets. Brooks thought it was essential that young people have the opportunity to express themselves. “A teacher cannot create a poet,” she once said, but “a teacher can oblige the writing student to write.” The covers of these books, like the writing exercises in them, are simple and inviting, aiming to introduce a new generation to the joy of poetry.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Young Poet’s Primer

Chicago: Brooks Press, 1981

Very Young Poets

Chicago: Brooks Press, 1983

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198652, PML 198653

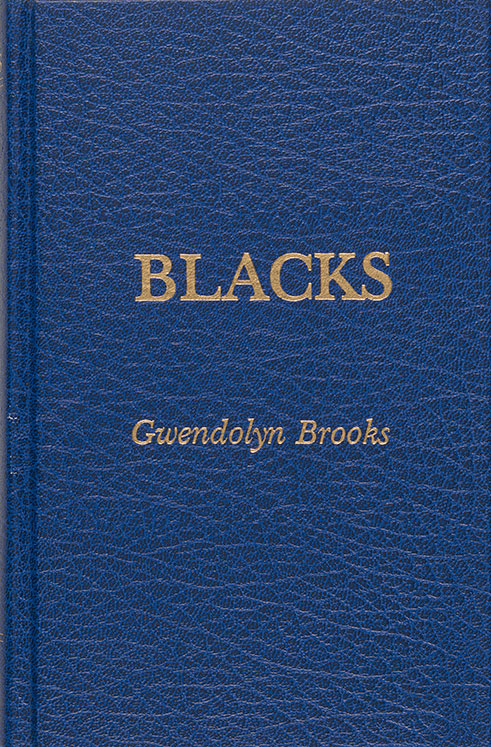

Blacks

Blacks, the largest collection of Brooks’s work, was designed by the poet—an advantage of self-publishing that she valued greatly. The deep-blue binding and gilt cover evoke a Bible or dictionary, at once aesthetically pleasing and meant for everyday use and consultation. The dust jacket’s simple design is a trademark of Brooks’s self-published volumes. The David Company, her second imprint, was named in honor of her father, David Anderson Brooks. Gwendolyn credited his habit of singing and reciting poetry throughout the house with inspiring her to write poems in her youth. These tender moments are present in her poetry as an inspiration for all who read.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Blacks

Chicago: David Company, 1987

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2021; PML 198691