A Black Arts Community Leader

The Black Arts Movement initiated a radical shift from the predominantly White mainstream art world, allowing Black artists to create their own institutions and metrics for what was considered art. The movement introduced a visual language that emphasized Black cultural history and celebrated Afrocentric imagery. In the 1960’s and 70s, Gwendolyn Brooks found alignment with this large artistic and political community.

The Black Arts Movement initiated a radical shift from the predominantly White mainstream art world, allowing Black artists to create their own institutions and metrics for what was considered art. The movement introduced a visual language that emphasized Black cultural history and celebrated Afrocentric imagery. In the 1960’s and 70s, Gwendolyn Brooks found alignment with this large artistic and political community.

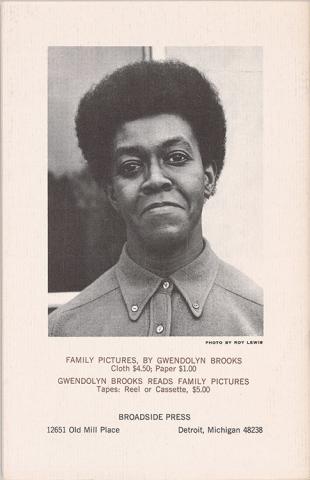

Back cover of Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000), Family Pictures (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1970)

Photograph by Roy Lewis (b. 1937)

The Morgan Library & Museum, PML 198515.

© Broadside Lotus Press

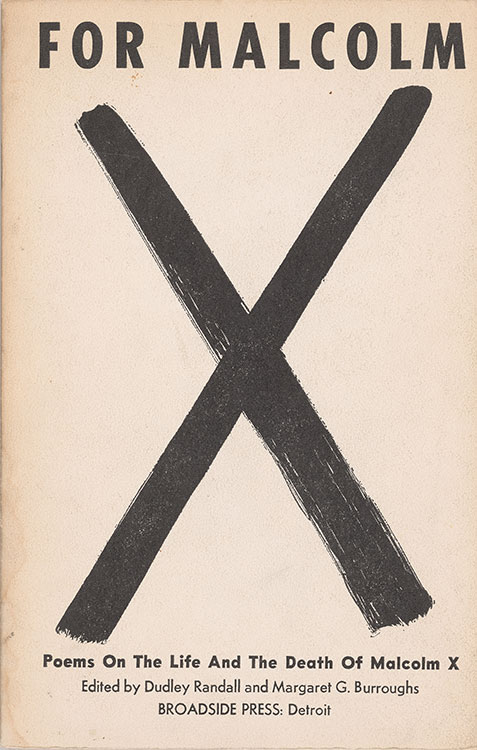

For Malcolm: Poems on the Life and the Death of Malcolm X

It is the task or job or responsibility or pleasure or pride of any writer to respond to his climate.

—Gwendolyn Brooks

The 1960s assassinations of two great African American leaders, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, mobilized the Black Power movement, an international campaign against anti-Black racism. Brooks, like many Black writers, felt the need to address these tragedies and their repercussions. The Black-owned Broadside Press responded to that need, publishing work that emphasized issues of identity, cultural history, racial justice, and community uplift. Broadside’s first book of poems, For Malcolm, provided a space for Black authors to speak about the life, work, and death of the prominent leader.

For Malcolm: Poems on the Life and the Death of Malcolm X

Edited by Dudley Randall (1914–2000) and Margaret G. Burroughs (1915–2010)

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1967

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198544

Riot

Reflecting her newly urgent interest in racial consciousness, Brooks changed publishers in 1970, switching from the major press Harper & Row to the small, new Broadside Press. “Everyone who’s black,” she said, “ought to have a black publisher.” In Riot, her first book of poetry released by Broadside, Brooks documents reactions of the global Black community to the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Working with Broadside gave Brooks more freedom to speak directly to Black audiences. In return for this freedom, she donated all royalties from Riot back to the press. With Brooks’s backing, Broadside became a central asset to the Black Arts movement. Known today as Broadside Lotus Press, it is one of the oldest Black-owned US publishers still in operation.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Riot

Design by Cledie Taylor (b. 1926)

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1970

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198519

© Broadside Lotus Press

Riot

A riot is the language of the unheard.

—Martin Luther King Jr., epigraph of Riot

A poem in three parts, Riot, like 1968’s In the Mecca, is more experimental and directly political than Brooks’s early work. Allah Shango, the frontispiece by AfriCOBRA cofounder Jeff Donaldson, shows two young men behind a sheet of glass. One holds a long African statuette and seems poised to smash it through the invisible barrier at any moment. The text of Riot announces that young Black people are prepared literally to fight back against oppression. Its design was meant to unsettle any White audiences and proclaim Black cultural authority.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Riot

Frontispiece by Jeff Donaldson (1932–2004)

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1970

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198520

The Estate of Jeff Donaldson, courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery, New York. © Broadside Lotus Press

"We Real Cool"

The creators of the Black Arts movement wanted to reach the widest possible Black audience. To do so, writers had to “bring poetry to the people,” wherever they were. It was with this in mind that Broadside Press launched its Broadside Series, printing single poems on sheets of paper with eye-catching designs. Often sold for a few cents, these sheets were meant to be passed around, hung up, and pasted on city walls. The ethos of this format, which made poetry accessible at minimal cost, also inspired the press’s name. When publisher Dudley Randall started the series, he asked Brooks if she would contribute a poem. Brooks replied, “You can use any poem I have,” resulting in this striking print of her 1960 work “We Real Cool,” designed by Cledie Taylor.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

“We Real Cool”

Design by Cledie Taylor (b. 1926)

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1966

Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Call no. Broadside Ludwig 461. Reprinted by Consent of Brooks Permissions

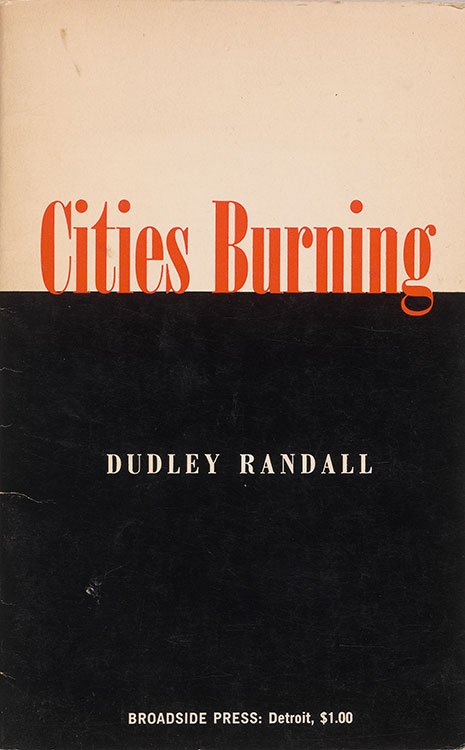

Cities Burning

Created by the Black poet Dudley Randall in 1965 without any blueprint, savings, or investors, Broadside Press survived and grew through the support of Black artists and its international Black readership. In the press’s early years, Randall and his associates worked out of a single room in his home. The first publications were high quality but produced in relatively small numbers, which allowed them to be printed quickly and at a low cost. Like the press’s broadside poems, the covers of its books featured bold designs by Black artists. Randall also used Broadside to print his own work, which mainstream publishers had refused due to its subject matter, including discussions of state violence and the need for new representations of Black life.

Dudley Randall (1914–2000)

Cities Burning

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1968

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198554

© Broadside Lotus Press

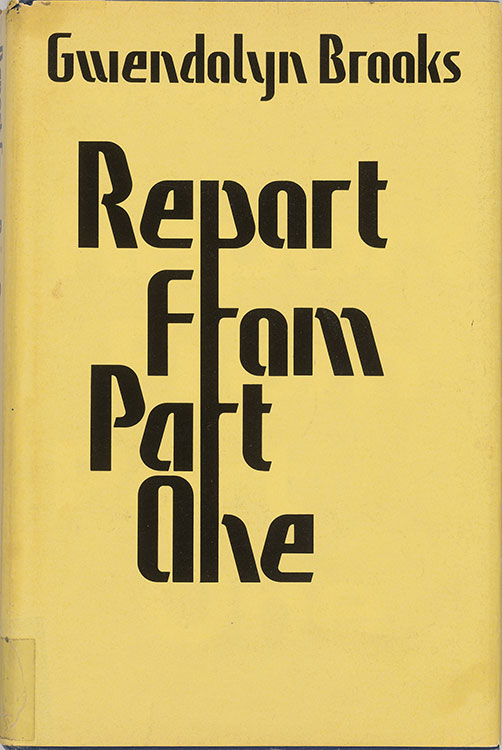

Report from Part One

When Brooks developed her first memoir project, Report from Part One, she insisted that it be printed by Broadside Press. The result was an experimental book containing interviews, letters from the poet’s parents and children, and approximately eighty photographs—personal family pictures as well as snapshots of collaborators, colleagues, neighbors, and other community members, many taken by photographer Roy Lewis. Brooks dedicated the book to these friends and fellow Black artists who fed her creativity and work. The inclusion of these names and photos in Brooks’s memoir shows how integral community was in her life, introducing a collective impulse into the tradition of autobiographical writing.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Report from Part One

Photographs by Roy Lewis (b. 1937) and others

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1972

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198522

Think Black

Brooks proclaimed that a younger generation of artists—including Knight, Sanchez, Madhubuti, and Giovanni—were “turning Black poetry around” by writing with new energy about Black life and experience. She lauded their self-awareness, their fresh perspectives on long-standing issues, and the urgency and directness with which they wrote and performed. Brooks both supported and learned from these young artists: she joined them for readings in parks, housing projects, prisons, and taverns, thus connecting with previously unreached audiences. Many of the volumes shown here are from Brooks’s own library and include personal inscriptions to the poet by her mentees.

Don L. Lee (b. 1942; a.k.a. Haki R. Madhubuti)

Think Black

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1967

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198541

© Broadside Lotus Press

Nikki Giovanni (b. 1943)

Black Feeling, Black Talk, Black Judgement

New York: William Morrow, 1970

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198533

Autograph postcard

As Brooks became further engaged with the ideas of heritage and unity aligned with the Black Arts movement, it became increasingly important for her to travel to what she called “Mother Africa”—a trip she would take several times throughout her later life. On her first African journey in 1971, she visited Nairobi, where she was filled with both “warm joy and an inexpressible sadness” for the history that separated her from the land. In this postcard written to her friends and former editors Roslyn and Bill Targ, Brooks describes Kenya as “beautiful beyond belief.” Brooks found the experience so valuable that, after becoming a writing teacher, she periodically subsidized her students’ trips not only to Kenya but also Ghana and South Africa.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Autograph postcard, signed: Nairobi, to William and Roslyn Targ, 1971 July 20.

The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; MA 8569.21

Reprinted By Consent of Brooks Permissions

Family Pictures

Brooks kept a habit of writing poetry to and about her friends and fellow poets. The collection Family Pictures speaks to the importance of these relationships, containing poems about people Brooks considered “kin.” The central theme of the book is solidarity and unity in the face of global anti-Blackness, and the section “Young Heroes” contains dedication poems that show Brooks’s admiration and support of a new generation of Black writers in the United States and abroad. “Keorapetse Kgositsile,” for example, is titled after the South African Tswana poet, journalist, and political activist.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Family Pictures

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1970

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198515

© Broadside Lotus Press

To Gwen with Love

Writer and educator Hoyt Fuller, in his introduction to the anthology To Gwen with Love, calls the volume a “gesture of affection and respect.” Its production was inspired by a 1969 tribute to Brooks that took place at the Affro-Arts Theater in Chicago, directed by actress Val Gray Ward, a friend of the poet’s. During the tribute, Black artists from around the country gathered to honor Brooks with performances, speeches, poetry, and music. This volume is a fitting testament to her influence, containing poems, fiction, essays, and illustrations from over sixty contributors. The cover design, created by artist Jeff Donaldson in his unique and colorful style, features Brooks surrounded by the titles of her published books.

To Gwen with Love

Edited by Patricia L. Brown, Haki R. Madhubuti (b. 1942; a.k.a. Don L. Lee), and Francis Ward (b. 1935)

Introduction by Hoyt Fuller (1923–1981)

Cover by Jeff Donaldson (1932–2004)

Chicago: Johnson Publishing, 1971

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2021

The Estate of Jeff Donaldson, courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery, New York.

Victory In The Valley of Eshu

The Black Arts movement initiated a radical shift from the predominantly White mainstream art world, allowing Black artists to create their own institutions and metrics for what was considered art. The movement introduced a visual language that emphasized Black cultural history and celebrated Afrocentric imagery. Jeff Donaldson, cofounder of the artists’ collective AfriCOBRA and contributor to the mural the Wall of Respect in Chicago, used color and shape to represent Black subjects dynamically. His piece Victory in the Valley of Eshu speaks to the Black Art movement’s experimental nature.

Jeff Donaldson (1932–2004)

Victory in the Valley of Eshu, 1971

Watercolor, ink, gold paint, and cut-paper collage on cardboard

Courtesy Kravets Wehby Gallery, New York