A Poet in Bronzeville

Gwendolyn Brooks was born in 1917 in Kansas to David Anderson Brooks, a custodial worker, and Keziah Brooks, a schoolteacher. Shortly after Gwendolyn’s birth, her parents moved the family to Chicago, where she would reside for the rest of her life. Raised in the South Side neighborhood of Bronzeville, Brooks started exploring creative writing at a young age. She kept a poetry journal from the age of eleven, and by the time she turned thirteen, her poems were being published in a local newspaper as well as a national magazine, American Childhood. Quiet by nature, a young Brooks used poetry to speak the truths that her family, experiences, and surroundings taught her. She found those surroundings to be a rich subject for her poems.

Gwendolyn Brooks was born in 1917 in Kansas to David Anderson Brooks, a custodial worker, and Keziah Brooks, a schoolteacher. Shortly after Gwendolyn’s birth, her parents moved the family to Chicago, where she would reside for the rest of her life. Raised in the South Side neighborhood of Bronzeville, Brooks started exploring creative writing at a young age. She kept a poetry journal from the age of eleven, and by the time she turned thirteen, her poems were being published in a local newspaper as well as a national magazine, American Childhood. Quiet by nature, a young Brooks used poetry to speak the truths that her family, experiences, and surroundings taught her. She found those surroundings to be a rich subject for her poems.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Annie Allen

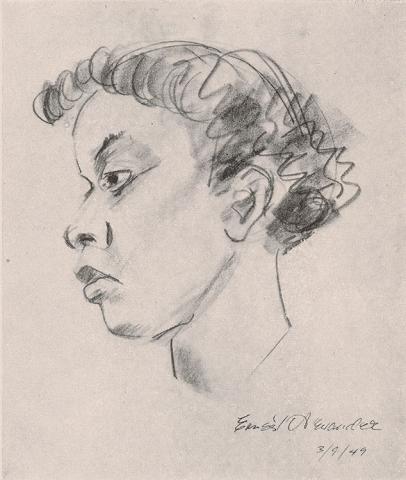

Frontispiece by Ernest Alexander (1921–1974)

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949

The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 184291

Used with the permission of the Estate of Ernest Alexander.

A Street in Bronzeville

If you wanted a poem, you had only to look out of a window. There was material always, walking or running, fighting or screaming or singing.

—Gwendolyn Brooks

Brooks’s first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville, was influenced by the people that she connected with and observed on the streets of her neighborhood in Chicago. In these poems, Brooks portrays scenes of urban Black daily life, a topic that was otherwise ignored in popular writing at the time. Her subjects are the preacher, the working woman, the married couple, the schoolgirl. Brooks’s empathetic treatment of the day-to-day lives of African American people, from dealing with systemic racism and poverty to celebratory moments of joy and love, paints intimate and relatable portraits of her community.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

A Street in Bronzeville

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1945

The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 184293

"We're the Only Colored People Here"

“We’re the Only Colored People Here” was printed in the inaugural volume of Black Sun Press’s Portfolio: An Intercontinental Quarterly. Brooks’s short story, excerpted from the manuscript that would become the novel Maud Martha (1953), is told from the perspective of a couple attempting to enjoy a night at the theater despite the uncomfortable reality alluded to in the title. Created by Caresse Crosby, an American expatriate and publisher in Paris, as an “exchange of thought between America and Europe,” Portfolio showcased avant-garde writers and artists. Notably, Brooks was the only Black writer whose work was featured in the volume, alongside that of Henry Miller, Kay Boyle, Karl Shapiro, and others.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

“We’re the Only Colored People Here”

Portfolio: An Intercontinental Quarterly 1 (Summer 1945)

The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 182562.1

Reprinted By Consent of Brooks Permissions

Annie Allen

Brooks made history in 1950 by becoming the first African American recipient of a Pulitzer Prize. Annie Allen, the winning book of poetry, tells a story in three parts of a young African American woman coming into adulthood during World War I. With formal and technical precision, Annie Allen explores the title character’s struggles with love, loss, and growing up, casting them in an epic light. The frontispiece, a soft rendering of the poet’s profile by her friend Ernest Alexander, may have been the first likeness of Brooks that readers had seen. The novel Maud Martha follows themes similar to those in Annie Allen: though the former is Brooks’s sole work of fiction, both books are partly autobiographical.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Annie Allen

Frontispiece by Ernest Alexander (1921–1974)

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949

Used with the permission of the Estate of Ernest Alexander.

Maud Martha

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1953

The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 184291, PML 184292

In the Mecca

In 1967 Brooks’s participation at the Black Writers’ Conference at Fisk University made an indelible impact on her. Among the other speakers was Amiri Baraka, a vocal member of the Black Arts movement whose poetry raged against oppression. He joined like-minded poets in writing exclusively and directly to a Black audience, creating a sense of fellowship, instilling the power of self-determination, and rejecting racist institutions. Conversation at Fisk revealed to Brooks the possibilities of liberation in Black solidarity, and she would return home and do what she did best: write. In the Mecca centers on the Mecca Flats apartment complex in Chicago but also expands beyond it, connecting the disillusioned inhabitants of the dilapidated building to people suffering the conditions of racism everywhere.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

In the Mecca

New York: Harper & Row, 1968

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2021; PML 198679