Women Artists and Patrons in the Natural Sciences, 1650–1800

As both artists and patrons, women played an important role in the development of the natural sciences in the early modern period. While often excluded from working in more prestigious genres, such as history painting, female artists could establish successful and lucrative careers in the fields of zoological and especially botanical illustration. Similarly, while proper humanist education was generally inaccessible even to wealthy female aristocrats, the natural sciences were a niche in which women could actively participate and achieve recognition—by cultivating expansive gardens, collecting plants and other specimens, and recording their discoveries. Working closely with artists, patrons like Agnes Block (1629–1704) and Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, Duchess of Portland (1715–1785), documented and disseminated information about their rich holdings during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Especially in the early part of the period, the division between art and science was not as clearly delineated as it is today. Many women artists not only skillfully recorded specimens but also produced new knowledge about them, simultaneously inhabiting the two spheres. Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) exemplifies this dual focus, having researched and published a brilliantly illustrated treatise on the metamorphosis of insects, a subject only partially understood in her day.

On view September 14, 2021 through January 9, 2022.

Overview

Herman Saftleven

Although she received no formal scientific education, Agnes Block (1629–1704) was a passionate horticulturalist and collector of plants and flowers. She cultivated them, mostly from seed, in her garden at Vijverhof—a country house on the River Vecht, southeast of Amsterdam, that Block bought after the death of her first husband, in 1670. It was her practice to document her collection by commissioning watercolors from artists. Between 1680 and 1684, at the tail end of a career spent producing Italian and Dutch landscapes and genre scenes, Herman Saftleven made a number of such studies at Block’s request. The verso of this sheet is inscribed, in Block’s hand, with the correct Latin names of the individual plants and the months when they flowered.

Herman Saftleven

Dutch, 1609–1685

Studies of Five Flowers and Plants, 1682

Watercolor, opaque watercolor, and gum arabic

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased on the Fellows Fund; 1984.10

Alida Withoos

Withoos trained as a painter and specialized in depictions of plants, animals, and insects in watercolor and oil. This vibrant study of a nasturtium is a great example of her style of botanical drawing, which was admired by contemporary Dutch horticulturalists and botanists, including Agnes Block. Withoos skillfully layered transparent and opaque watercolor washes to describe the fiery striped petals and convey the color and texture of nasturtium’s distinctive shield-shaped leaves. Following the conventions of botanical illustration at the time, she depicted the plant at several stages of growth—from buds to flowers to seeds. Withoos also observed her subject from numerous vantage points, showing both the upper and lower sides of leaves and blossoms.

Alida Withoos

Dutch, 1659–1715

Nasturtium, ca. 1675–1715

Watercolor and opaque watercolor over black chalk

The Morgan Library & Museum, Bequest of Charles Ryskamp; 2010.179

Willem de Heer, Maria Sibylla Merian

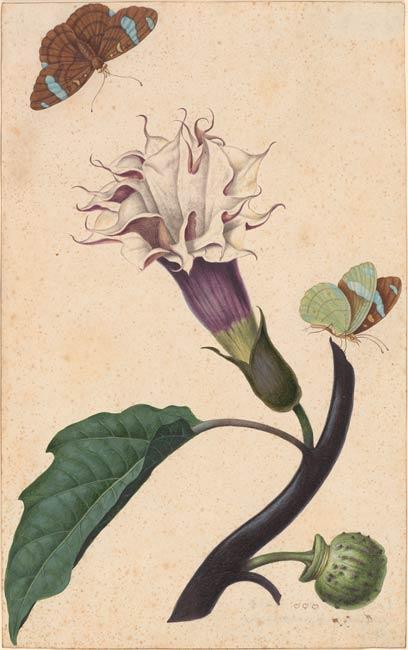

Unusually, this drawing was executed in two distinct stages. The night-blooming datura—a flower that was not native to the Dutch Republic—was drawn by De Heer in 1679. The artist seems to have marveled at the complex anatomy and subtle coloration of the plant, which in this drawing achieves an almost sculptural quality. The two butterflies were added by Merian sixteen years later. Although they give the impression of playfully fluttering around the plant, the insects were rendered in a scientific manner, allowing both their inner and outer wings to be easily observed. The inscription on the verso indicates that the addition of the butterflies was commissioned by Agnes Block, one of Merian’s great patrons.

Willem de Heer

Dutch, 1637/38–1681

Maria Sibylla Merian

German, 1647–1717

Datura with Butterflies, 1679/95

Watercolor and opaque watercolor, with traces of gum arabic, over graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, Bequest of Charles Ryskamp; 2010.160

Maria Sibylla Merian

Merian was one of the most celebrated naturalists and scientific illustrators of her age. In 1699, she traveled from Amsterdam to Suriname, then a Dutch colony, in South America. While the artist was particularly interested in studying the metamorphosis of insects, she also depicted plants and animals native to the land. The expedition resulted in the publication of the Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium—a groundbreaking treatise that described many species previously unknown in Europe. This drawing served as a preparatory study for a plate included in the expanded second edition of the book. Merian’s powers of observation and her inimitable artistry are exemplified by her description of the structure of the lizard’s body and the texture and pattern of its scales.

Maria Sibylla Merian

German, 1647–1717

Black Tegu Lizard (Tupinambis teguixin), ca. 1701–15

Pen and black ink, and watercolor and opaque watercolor, on vellum

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased on the Sunny Crawford Von Bülow Fund 1978; 2001.10

Attributed to Attributed to Johanna Helena Herolt

Herolt, Maria Sibylla Merian’s eldest daughter, was also a talented artist. She often collaborated with her mother and worked in a similar style, which can make it difficult to distinguish between the two women’s drawings. In this sheet, which brings together the plant and animal kingdoms, mice are depicted nibbling on nuts and acorns. Although the three scenes are completely discrete, the dynamic composition imbues the image with a narrative quality. The white mouse gazes directly at the viewer, which creates a sense of engagement unusual for a scientific illustration.

Attributed to Johanna Helena Herolt

German, 1668–ca. 1723

Three Mice with Walnuts, Almonds, Hazelnuts, and Acorns, ca. 1690–1710

Watercolor and opaque watercolor on vellum

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased on the Fellows Fund, with the special assistance of Mrs. Carl Stern and Mrs. Lawrence Hughes; 1979.37

Sarah Stone

Around 1777, Stone was employed by Sir Ashton Lever (1729– 1788)—a collector and businessman and the owner of a museum of natural history and ethnography in Leicester Square, London. The seventeen-year-old artist was tasked with making watercolor studies of the museum’s ornithological, zoological, and ethnographical holdings, many of which were obtained during British expeditions in the 1770s and 1780s. The subject of this work, the greater racket-tailed drongo, is native to Asia and distinguished by its elongated outer tail feathers. Working with a fine brush, Stone brilliantly captured the bird’s iridescent bluish-black plumage. Although the artist received a degree of early success and recognition, her output slowed dramatically after her marriage in 1789.

Sarah Stone

British, 1760–1844

Greater Racket-Tailed Drongo (Dicrurus paradiseus), 1782

Watercolor and opaque watercolor over graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased on the Charles Ryskamp Fund; 1998.30

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte or her circle

According to an obituary published in 1781, Basseporte, who began her career as a portraitist, turned to scientific illustration because it provided a more reliable source of income, allowing her to support her widowed mother. She was exceedingly suc- cessful in this line of work, becoming the first woman to occupy the position of official painter of the Jardin du roi, the royal botanical gardens in Paris. This study of a crown imperial marries scientific description with dazzling illusionism. Although the plant is placed against a blank background, parts of the stem, leaves, and green “crown” extend beyond the embellished double border, playfully exploring the boundary between image and reality.

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte or her circle French, 1701–1780

Fritillaria imperialis (Crown Imperial), ca. 1750

Watercolor over graphite on vellum

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Junius S. Morgan and Henry S. Morgan; 1952.29:64

Ann Lee

Ann Lee was born to a family of Scottish botanists and horticulturalists. James Lee, her father, ran a successful nursery in the Hammersmith area of London, introducing many foreign species to English cultivation. Admired for his encyclopedic knowledge of plants, James communicated with renowned naturalists of his day, including Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), the famed Swedish botanist and zoologist. While some of the Lee children worked in the family business, Ann, the youngest daughter, received an early and rigorous training in the art of botanical illustration. In this drawing, she confidently and accurately renders the plant’s delicate serpentine stem, coarsely toothed leaves, and white blooms accented with distinctive purple lips.

Ann Lee

British, ca. 1753–1790

Mellittis melissophyllum (Bastard Balm), 1771

Opaque watercolor over graphite on vellum

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1978.13

Georg Dionysius Ehret

This study of a coral tree and the adjacent watercolor of a bastard balm belong to a group of 108 botanical drawings from the private collection of Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, Duchess of Portland (1715–1785), acquired by the Morgan in 1978. Widowed for over twenty years and extremely wealthy, the duchess devoted herself to the study of natural history, accumulating a vast collection of both foreign and domestic specimens that she referred to as the Portland Museum. Ehret, the foremost botanical illustrator in eighteenth-century England, produced hundreds of watercolors of plants in the duchess’s collection and was retained by her as a drawing teacher.

Georg Dionysius Ehret

German, 1708–1770

Erythrina (Coral Tree), 1761

Opaque watercolor on vellum

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1978.8:19