Drawing Modernity

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, drawing continued to play a seminal role in the creative process. Adolph Menzel, in keeping with his personal motto Nulla dies sine linea (Not a day without a line), was almost fanatical about exploring the visible world in his sketches. Similarly, nearly twenty thousand surviving sheets by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner demonstrate the artist’s urge to, in his own words, “draw to the point of madness.” Like their predecessors, these artists used drawing for unfettered explorations of new visual imagery; as a means of developing ideas for works in other media, such as paintings and prints; and to produce finished works of art. During the period of the Weimar Republic (1919–33), the Kupferstich-Kabinett actively acquired works by living artists, and many of the drawings on view here entered the museum’s collection shortly after their creation. The policies of the Nazi regime (1933–45), however, resulted in the confiscation and loss of many modern drawings that did not adhere to the cultural ideology of National Socialism and were deemed “degenerate.”

Adolph Menzel

These expressively charged studies stem from a trip that Menzel made to Italy in 1881. Rather than visit more popular destinations like Florence or Rome, the artist traveled to Verona, where he filled sketchbooks with firsthand studies of the characters and bustle of the city’s main market. Back in Berlin, Menzel used this visual repository as the basis for more elaborate drawings such as this one, made in preparation for his painting Piazza d’Erbe in Verona. The sheet is a superb example of Menzel’s mature style and his virtuosic control of the pencil, with which he was able to alternate fluently between broad, dynamic contour and refined details, confidently smudging the soft graphite to establish finely graded shadows.

Adolph Menzel

German, 1815–1905

Studies of a Crouching Man with Hammer and Chisel, 1883

Graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1886-10

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Käthe Kollwitz

In 1844, several thousand weavers in the central European region of Silesia revolted against exploitative working conditions and decreasing wages. Kollwitz’s Weavers’ Revolt, a series of six prints completed in 1897, draws on these historic events but places them in a contemporary context. A preparatory study for the final image in the series, this drawing depicts the tragic consequences of the unrest. At left, men carry a corpse into a dark parlor, to be laid down next to the two dead bodies already there; a woman sits beside them, grieving. Although the revolt itself is left out of the image, the white gunpowder haze, which drifts into the interior space through the broken window, suggests that the fighting is ongoing.

Käthe Kollwitz

German, 1867–1945

The End, 1897

Graphite pencil, brush and pen and black and brown ink, heightened with white

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1918-21

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Herbert Boswank

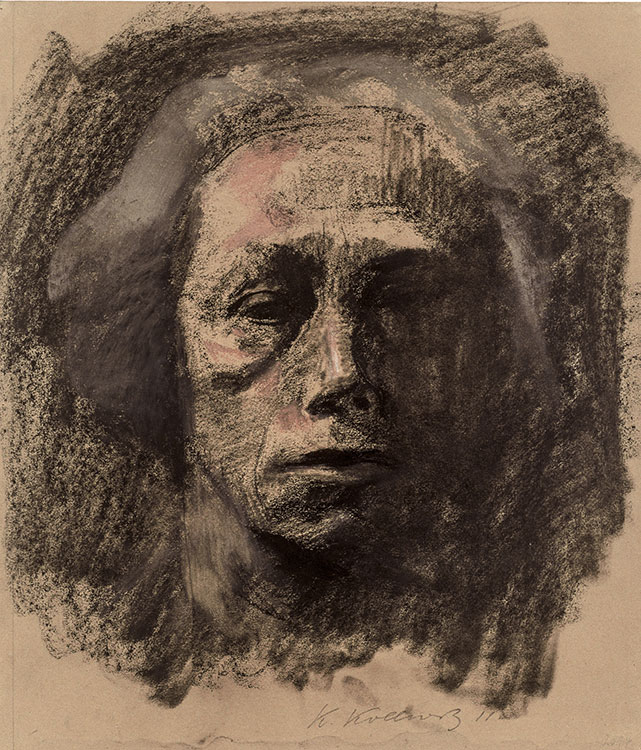

Käthe Kollwitz

Between 1888, when she began her art studies in Munich, and her death in 1945, Kollwitz made scores of self-portraits in which she interrogated her appearance and her state of mind in a direct and uncompromising way. Although the deep rings surrounding her eyes and the gray hair can be interpreted as signs of aging, the artist was only forty-four years old when she made this work. The likeness is rendered predominantly in black chalk, with touches of violet accentuating her cheekbones and forehead. Covered in dense hatching, the left side of the artist’s face dissolves into the darkness and merges with the rapidly sketched background.

Käthe Kollwitz

German, 1867–1945

Frontal Self-Portrait, 1911

Black chalk, heightened with violet and gray chalk, with stumping, on grayish-brown paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1917-50

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

Kollwitz’s weathered face aligns her with the struggling figures depicted in her print series, blurring the line between artist and subject. She executed this introspective sheet just after she began to engage intensively with sculpture and investigate more deeply three-dimensional structures. Her choice to depict herself with frank weariness suggests that her work chronicling the injustices and indignities of modern life took a physical toll. That she produced so many self-portraits over time allows for the somewhat eerie experience of being able to watch her age before our eyes. It also gives us a more vivid sense of her as a person, adding a rich biographical dimension to her works on paper.

Gustav Klimt

Klimt’s portrait of a young woman in strict profile is striking for both its economy of means and stark visual contrasts. The artist mostly eschewed modeling, delineating the young woman’s features with concise contours. He first drew the nude figure before adding the more abstractly rendered dress, under which the lighter, initial graphite lines can still be seen. Klimt retraced and reinforced the young woman’s chin and neck with a more incisive line set against hatching in the negative space, placing her face in sharper relief. The artist also exploited the juxtaposition of darker graphite with the white of the sheet to brilliant effect, accentuating the form of her lips, lowered eyelid, and arched eyebrow.

Gustav Klimt

Austrian, 1862–1918

Portrait of a Girl in Profile Facing Left, ca. 1904–7

Graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1922-2

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Toulouse-Lautrec’s expressive study captures the deep concentration of a musician at work. The drawing was made during an informal performance by Misia Natanson, a talented pianist and patron of the arts. Toulouse-Lautrec depicted Natanson on several occasions in different media, including a painted portrait that the artist named after Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ruins of Athens. In her autobiography, Natanson recalled that Toulouse- Lautrec “had fallen in love with Beethoven’s musical piece. I had to play it for him constantly because he claimed to draw his inspiration from it.”

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

French, 1864–1901

Seated Woman Looking toward the Left (Misia Natanson at the Piano), 1895

Red chalk on blue paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1903-28

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Andreas Diesend

Ian Hicks, Moore Curatorial Fellow

Toulouse-Lautrec produced this study during an informal performance by its sitter, Misia Natanson, a talented musician and patron of the arts. Using red chalk against the mid-tone of the blue paper, the artist focused his attention on Natanson’s facial features, sensitively rendering the deep concentration they convey. Toulouse-Lautrec depicted the musician on several occasions and in different media. In her autobiography, Natonson recalled that the artist had named a painted portrait of her after Beethoven’s “Ruins of Athens.” She remembered that Toulouse-Lautrec had fallen in love with the piece, which she had to play for him constantly as he claimed to draw inspiration from it. Intimate portraits such as this can therefore be understood as deeply personal works by the artist, inspired not only by the visual world and his relationship with the sitter, but also with the music she produced during their making.

The sheet entered the Kupferstich-Kabinett’s collection as an indirect result of their acquisitions of contemporary art at the turn of the twentieth century. The drawing was one of four sheets given to the collection by the artist’s mother in 1903, two years after Toulouse-Lautrec’s death. She offered the gift in thanks to the institution for supporting her son by acquiring his works during his lifetime.

Piet Mondrian

In 1926, Mondrian was asked to design the interior of the Damenzimmer (ladies’ salon) in the house of the Dresden art collector Ida Bienert, a driving force for modernism in the city. Although the commission was never realized, the artist’s visionary design is preserved in this master plan, which combines the floor layout, wall sections, and ceiling view. To produce the plan, Mondrian extended the principles of Neo-Plasticism—an aesthetic theory that eschewed naturalistic representation in favor of straight lines, rectangular shapes, and primary colors—into the three-dimensional interior space. The resultant design is composed of clearly outlined and meticulously arranged fields of color. Mondrian attached great importance to the furnishings of the room, which were incorporated into the plan and strongly stylized.

Piet Mondrian

Dutch, 1872–1944

Color Design for the Salon of Ida Bienert (Floor Plan / Vertical Plan, Full View), 1926 Opaque watercolor over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1982-151

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, ©2020 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Austeja Mackelaite, Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator of Drawings and Prints

Ida Bienert was a driving force for modernism in Dresden in the early twentieth century. Her marriage to Erwin Bienert, a member of a wealthy family of mill operators, allowed her to support young artists and engage in social causes. In 1906, Bienert established the first public library in Saxony. Her social circle included Bauhaus artists, such Walter Gropius and Paul Klee, as well as important German and Austrian expressionists, such as Oskar Kokoschka and Otto Dix, whose works are on view elsewhere in this exhibition.

Bienert commissioned Piet Mondrian to design an interior for one of the rooms in her family’s Dresden home in 1926. Using the design principles of Neo-Plasticism, Mondrian created a plan composed of meticulously rendered rectangular shapes in primary colors. He even incorporated references to furniture—such as the white oval, meant to represent a table, in the center of the plan. It seems that the artist shared Bienert’s interest in aesthetically balanced and pleasing interior spaces. He wrote that for an aesthetic person, [I quote] “a house or a room that is consistent with his nature are as necessary as food and drink, [because] for him the aesthetic is equivalent in value to the material.”

Ultimately, however, the design was never implemented—most likely due to logistical and financial reasons. As the parameters of Mondrian’s plan do not fully correspond to the actual layout of the room, unanswered questions remain about the practical implementation of the artist’s vision.

Hermann Glöckner

Between 1930 and 1937, Glöckner produced more than 150 panels known collectively as his “Tafelwerk.” Made on a stiff board composed of layers of cardboard repeatedly dipped in a hot glue solution, these sturdy, double-sided works can be understood as sculptural objects. While the artist was aware of the contemporary Constructivist movement, he worked in Dresden largely in isolation and developed his compositions independently. This panel was made toward the beginning of this intensely creative period. Glöckner implemented a systematic compositional approach, manipulating his geometric shapes so that corresponding fields of color on the recto and verso have the same surface area.

Hermann Glöckner

German, 1889–1987

White and Silver with a Black Wedge on Top, ca. 1932

Colored paper, tempera, board, and varnish

INV. NO. C 1980-546

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photo: Herbert Boswank

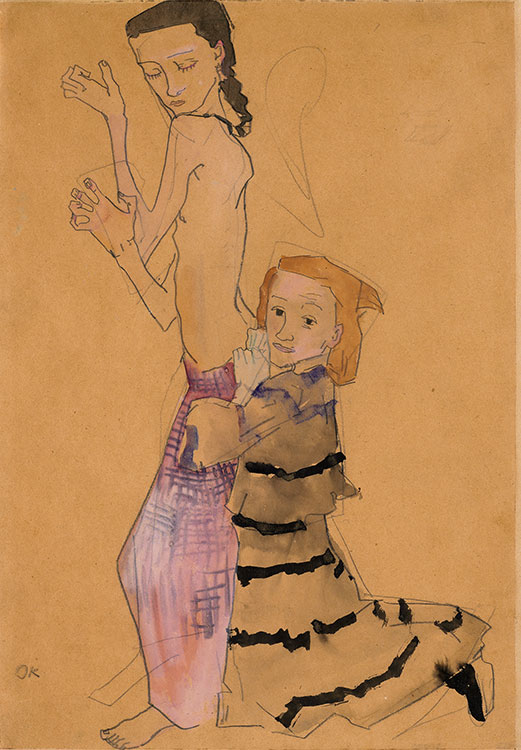

Oskar Kokoschka

A leading figure among the Austrian artists of his generation, Kokoschka rejected the idealized academic approach to the female body in favor of capturing the uninhibited poses and expressive movements of his models. In this early work, the sparse, angular quality of the artist’s line emphasizes the contorted pose of the standing girl. She is portrayed with her eyes closed and her head turned over her left shoulder, bending and flexing her outsize fingers. Her kneeling companion fastens the standing girl’s skirt, gazing toward but not directly at the viewer. The intimate, introspective atmosphere that permeates this sheet connects it with drawings and prints that Kokoschka was making for the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops) at this time.

Oskar Kokoschka

Austrian, 1886–1980

Two Girls Dressing (The Dress Rehearsal), 1908

Graphite pencil, brush and black ink, watercolor and opaque watercolor on brown paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 2014-68—WILLY HAHN COLLECTION

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden © 2021 Fondation Oskar Kokoschka / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ProLitteris, Zürich

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Otto Mueller

During the era of Nazi rule, Mueller was proclaimed to be a “degenerate” artist, and many works by him were removed from German art institutions. Acquired by the Kupferstich-Kabinett shortly after the end of World War II, this drawing attests to the museum’s attempt to fill in the gaps that had opened in its collection as a result of the Nazi seizures. The vividly colored work depicts three female bathers in a verdant landscape, rendered in Mueller’s intentionally schematic and two-dimensional style. It exemplifies the artist’s lifelong interest in idyllic pastoral settings, where the perfect unity of humanity and nature could be achieved.

Otto Mueller

German, 1874–1930

Three Nudes in the Forest, ca. 1920

Watercolor, colored chalks, and graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1946-3

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

In contrast to his friend Otto Mueller, who often portrayed female nudes in arcadian landscapes (as in the drawing on view nearby), Kirchner placed two bathers within the distinctly urban setting of an artist’s studio. At the center of the sheet, a model washes herself in a small flat-bottomed tub. At left, a turbaned figure drapes a towel around the shoulders of the second woman, who appears to have just stepped out of the bath. Angular lines and broken contours are surprisingly effective in describing the sensual physicality of Kirchner’s models. The hastily drawn object on a pedestal at right can be identified as Dancer with Necklace—a small wooden sculpture that the artist completed around the time this drawing was made.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

German, 1880–1938

Bathers, 1910–11

Graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1927-12

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Otto Dix

In this drawing, Dix portrays himself as a modern dandy in the middle of a bustling nightclub or brothel. His likeness is elegant and self-confident, with his brow furrowed and arms akimbo. A fashionably dressed couple dances behind him at left; at right, a jazz musician plays at a drum set. The complex image depicts the thrills and temptations of metropolitan life in the Weimar Republic shortly after World War I. The work’s title announces Dix’s departure from conventional aesthetic ideals, positioning his personal vision of beauty somewhere between the grotesque and the classical. The drawing served as a preparatory study for a large-scale oil painting now in the collection of the Von der Heydt-Museum in Wuppertal, Germany.

Otto Dix

German, 1891–1969

To Beauty, ca. 1922

Graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1965-8

Otto Dix

When World War I broke out in 1914, Dix voluntarily joined the German army as a machine gunner, fighting on both the eastern and western fronts. In works produced during the 1920s, the artist grappled with his wartime experiences and, in his own words, aimed to “depict the war objectively, without trying to arouse pity, without all the propaganda.” This sheet portrays two veterans in uniform with severe facial injuries inflicted by artillery shells. Rendered in watercolor washes that are almost disturbing in their vibrancy—from blue-purple bruises covering the soldiers’ faces to yellow and red scabs forming over their wounds—it emphasizes the immense human suffering resulting from military conflict.

Otto Dix

German, 1891–1969

In Memory of the Glorious Time, 1923

Watercolor and pen and ink

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1969-83

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. © Otto Dix / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Austeja Mackelaite, Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator of Drawings and Prints

Images of war preoccupied Otto Dix during the late 1910s and early 1920s. The artist had first-hand experience of fighting, because he had served in the German army as a machine gunner during World War I. While in the trenches, he was making powerful cubo-futurist drawings, aesthetically exaggerating and even glorifying the experience of being in the battlefield. In the later years, however, he came to see his military experience differently, emphasizing not the heroic struggle but the inhumane consequences of war.

This sheet portrays two veterans in uniform. The man at left wears the black and white ribbon of the Iron Cross Second Class—a military decoration that Dix had also received for his services during the war. Both men have brutal facial injuries inflicted by artillery shells. Their faces are covered with fresh bruises and bloody, festering wounds. The artist’s thick application of watercolor makes looking at the drawing into an almost tactile experience, as if the wounds have materialized on the sheet itself.

This was a personal work for Dix. He made the drawing in 1923 and inscribed “Not for sale” on the back of the sheet. Indeed, the drawing never entered the art market. It stayed with Dix for forty years, until 1969, and then entered the collection of the Kupferstich-Kabinett, as a gift from the artist.