Romantic Artists in Dialogue with Nature

At the close of the eighteenth century, as the political and cultural geography of Europe was shifting, Dresden became a major center for Romantic literature, philosophy, and art. A new enthusiasm for nature among artists led to the reevaluation and flourishing of the landscape genre. Caspar David Friedrich, who moved to the city in 1798, imbued his close studies of nature with an emotional and spiritual dimension. While Friedrich never traveled south of the Alps, works by the next generation of artists—Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Theodor Rehbenitz, Franz Theobald Horny, and Ernst Ferdinand Oehme—attest to the importance of a prolonged stay in Italy in the training and development of many northerners. Draftsmen made extensive use of watercolor and sepia washes, resulting in highly finished, painterly drawings that were appreciated as works of art in their own right. Actively collected by the Kupferstich-Kabinett during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, drawings from the Romantic period are one of the institution’s great strengths.

Adrian Zingg

After training as an engraver in his native Switzerland and working in Paris, Zingg moved in 1766 to Dresden, where he joined the faculty of the newly established Academy of Fine Arts. Combining topographical accuracy with a penchant for the picturesque, and taking inspiration from the local environment, his drawings paved the way for the Romantic landscape tradition that developed in Dresden in the nineteenth century. This large sheet depicts the Keppmühle—a charming mill that was one of the most popular excursion sites for Dresdeners at the time. The landscape is rendered in Zingg’s characteristically ornamental style, with extensive application of sepia washes and skilled use of the white of the paper, creating an enchanting impression of illumination.

Adrian Zingg

Swiss, 1734–1816

The Keppmühle near Dresden Hosterwitz, ca. 1794

Pen and black-brown and gray ink and brown wash

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1977-155

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Andreas Diesend

Caspar David Friedrich

This large sepia study attentively renders a constellation of boulders, stones, and pebbles scattered on a beach. Infused with quiet melancholy and devoid of signs of human presence, the work explores atmospheric conditions and the effects of light. It is difficult to know whether the luminous celestial body at the center of the composition is supposed to represent the moon or the sun. In either case, Friedrich’s predominant concern is depicting the moment of transition between night and day, darkness and light.

Caspar David Friedrich

German, 1774–1840

Stony Beach at Moonrise (Stony Beach with Setting Sun), ca. 1835–37

Brush and brown ink over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 2605

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Andreas Diesend

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

At the time he drew this sheet, Friedrich was entering his 60s and recovering from a lingering professional disappointment. A decade prior, he failed to ascend to the position of teaching landscape painting at the Dresden Academy and experienced a year long illness, events that left him pensive and increasingly isolated. After he suffered a stroke in 1835, he could no longer paint and resumed making wash drawings. Given Friedrich’s deep spirituality, it isn’t surprising that his late drawings reflect a more somber state of mind as he dwelled on thoughts of life’s end.

The reverence that he had for nature emerges in the way he wields his materials to evoke this tranquil coastal scene, devoid of figures. Friedrich returned to a sketch he had made of the beach at Rugen in 1801 and transferred part of it to this sheet. The evocation of this specific site at moonlight engaged Friedrich’s memory and lived experience, and this underlying sense of time’s passage lends an elegiac tone to this tranquil view.

Caspar David Friedrich

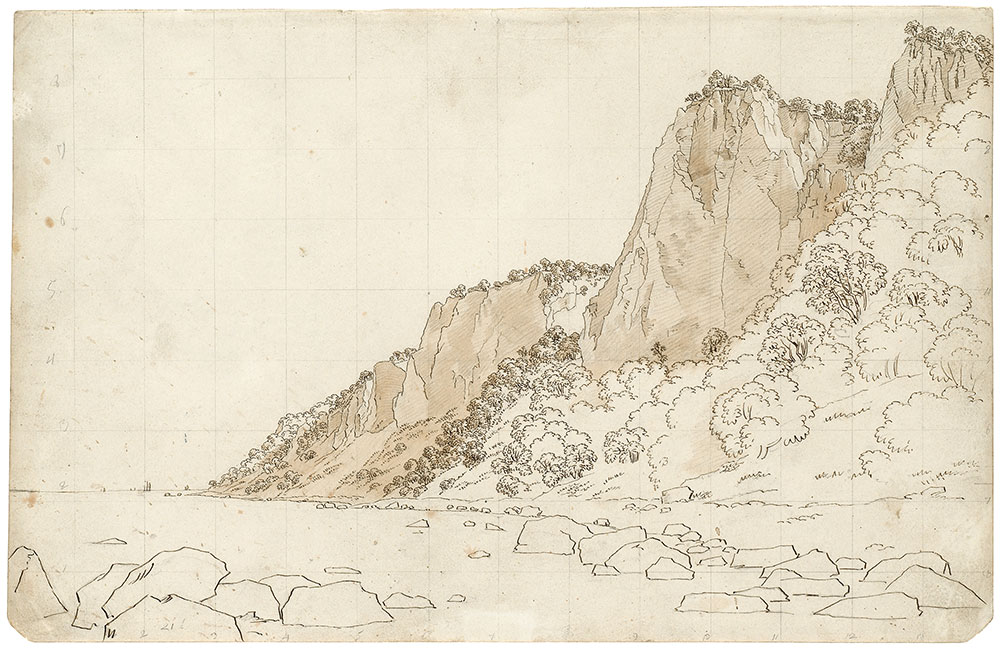

Rügen—a large island in the Baltic Sea, off the coast of Germany—was an important destination for Friedrich. The drawings he made during his numerous trips to the area focus on dramatic chalk cliffs and rugged, stony beaches, capturing the island’s austere, windswept character. In this sheet, the artist reduced the Rügen landscape to its most essential features, relying on clear, precise contours and sparingly applied washes. Friedrich frequently used the landscape motifs he developed in such works as the basis for highly finished sepia drawings, such as Stony Beach at Moonrise (Stony Beach with Setting Sun), on view nearby. In order to transfer his compositions to other formats, Friedrich often squared his sketches, as is the case here.

Caspar David Friedrich

German, 1774–1840

Stubbenkammer on Rügen, 1801

Pen and black ink and brown wash over graphite pencil; squared

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1968-357

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Joseph Anton Koch

Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, one of the most important works of medieval literature, was first translated into German at the turn of the nineteenth century. It immediately became a rich source of inspiration for Romantic artists; Koch alone produced over two hundred drawings and a large number of prints illustrating the text. In this sheet, the artist focused on the tale of Francesca and Paolo, who fall in love upon reading the story of the legendary knight Lancelot. While the couple is gently embracing in Francesca’s bedchamber at right, the left side of the composition is dedicated to the enraged, seething figure of Gianciotto— Francesca’s husband and Paolo’s brother—who has just discovered the illicit affair.

Joseph Anton Koch

Austrian, 1768–1839

Paolo and Francesca, 1802–5

Pen and brown ink over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1908-289

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Ian Hicks, Moore Curatorial Fellow

In addition to being one of the most important landscape painters of the early nineteenth century, Joseph Anton Koch was a writer and prolific draughtsman. After initial training in Stuttgart during his late teens and early twenties, the artist travelled to Switzerland to sketch the Alpine landscape. In early 1795, when he was twenty-six, the artist relocated to Italy. There, in addition to his heroic landscape paintings, Koch increasingly made figurative drawings, taking inspiration from classical, Medieval, and eighteenth-century literature.

In this drawing, we see the artist’s interest in literary narratives, namely his fascination with Dante’s Divine Comedy. The famous narrative poem was first translated into German at the turn of the nineteenth century and would become hugely influential for Romantic artists, including Koch, who produced over two hundred drawings related to the text. The artist here illustrates a scene from the ill-fated story of Francesca and Paolo, who fell in love with each other upon reading the story of the legendary knight Lancelot. The artist shows the moment when the lovers’ longstanding affair is discovered by Gianciotto – Francesca’s husband and Paolo’s older brother – who reaches to draw his sword before slaying the couple. The draughtsman’s pen brings a linear clarity to his more exploratory and energetic graphite sketch below. Though the figures are characterized by this precise approach with the pen, the agitated mass of Paolo’s cape and the more boldly rendered bed canopy lend the scene a dynamic charge.

Theodor Rehbenitz

In his self-portrait of 1817, Rehbenitz describes his intense gaze with precise and controlled draftsmanship. Feathery networks of graphite lines carefully establish the shadows over his face; the highly finished study is exactingly rendered throughout, apart from the loose curls at left, which remain as more animated traces of the artist’s hand at work. Rehbenitz produced this signed and dated drawing a year after moving to Rome from Vienna, where he had been studying at the Academy of Fine Arts. In Rome, Rehbenitz joined the circle of German artists known as the Nazarenes, forming a Protestant faction of the group with Friedrich Olivier and Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, whose work is on view nearby.

Theodor Rehbenitz

German, 1791–1861

Self-Portrait, 1817

Graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 3327

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Franz Theobald Horny

In this drawing, Horny treats the delicate lily branch as a monumental form. Placed against a vivid green-blue background, the flower fills almost the entire space of the sheet. Through the combination of pen and ink, graphite, and translucent watercolor, the topography of individual petals is carefully described. The dark background, composed of richly layered washes, further enhances the lily’s palpable three-dimensionality. Although the drawing would seem to be an end in itself, it is connected to the artist’s work on the ceiling decoration of the Dante Hall at the Casino Massimo in Rome.

Franz Theobald Horny

German, 1798–1824

Lily, 1817

Pen and brown ink and watercolor over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1908-225

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

On a forested hill overlooking the Villa Piccolomini near Frascati, two young men in Renaissance-style dress break from their pastoral concert as two women approach. Though the characters that populate Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s scene are imaginary, the detailed landscape punctuated by brightly lit trees, skillfully described using the reserve of the sheet, derives from firsthand study. During the artist’s extensive travels in Italy from 1818 to 1827, he produced over one hundred landscape drawings, which were later bound in an album. Reflecting on these Italian works in 1867, Schnorr von Carolsfeld reminisced about the “ten exceedingly happy days” he spent in the countryside around the Villa Piccolomini, where he made this drawing.

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

German, 1794–1872

Park and Villa Piccolomini near Frascati, 1826

Pen and brown ink with brown and gray wash over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1908-819

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Ian Hicks, Moore Curatorial Fellow

Schnorr von Carolsfeld was inspired toward the genre of landscape through the example of the previous generation of German and Austrian artists, including Joseph Anton Koch, whose work is displayed elsewhere in the exhibition. Following their example, Schnorr von Caroslfeld journeyed to Italy, where he travelled extensively from his mid-twenties into his early thirties, producing over a hundred landscape drawings that were later bound into an album. As the artist’s inscription along the lower margin makes clear, this drawing details the wooded hills overlooking the Villa Piccolomini, near the town of Frascati. The sheet is dated 1826, toward the end of his Italian sojourn.

While the landscape and the play of light record the artist’s careful observation of nature, the figures are an imagined fantasy. They are clad in Renaissance-style dress, perhaps inspired by the sixteenth-century villa. The scene isn’t clearly tied to a known narrative, but rather shows a more generic pastoral encounter between the two couples, evoking an Arcadian ideal. In writing a series of letters some forty years later to describe the drawings in his landscape album, Schnorr von Carolsfeld would reveal the pleasure he took in creating the work. He fondly reminisced over, as he put it, the “ten exceedingly happy days” he spent in the countryside around the Villa.

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

A key figure among German artists who lived and worked in Rome in the early nineteenth century, Schnorr von Carolsfeld received his initial training at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. This tender depiction of the ten-year-old Maria Heller dates to the end of his stay in that city. The artist captured the young girl as she slept, with her head and shoulder resting on a large pillow, and her feet protruding from underneath a light blanket. Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s use of crisp contours, sparing application of washes and hatching, and brilliant exploitation of the white of the paper itself result in an airy, ethereal image.

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

German, 1794–1872

Girl Lying Down (Maria Heller), 1817

Pen and brown ink with brown wash

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1938-30

Ludwig Richter

Made during Richter’s three-year stay in Italy, this drawing captures the vast, scenic landscape of the Roman countryside. The undulating hills extend rhythmically into the distance; they are composed of interchanging areas of gray and brownish washes, and sections of paper left blank. In the foreground, pious countrypeople are making their way to a small chapel located in a shaded valley at left. Unlike most of the landscape, the figures are rendered in outline only. While this gives the drawing an unfinished appearance, the artist likely left this area deliberately unworked to emphasize the impression of a radiant, sun-drenched Italian landscape.

Ludwig Richter

German, 1803–1884

Churchgoers near Rocca Santo Stefano, ca. 1824–25

Pen and brush and gray and brown ink and wash over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1908-948

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Ernst Ferdinand Oehme

Oehme’s vibrant watercolor shows a view of the mountainous Rigi area of Switzerland, which he visited in August 1825 on his return home to Dresden after a three-year stay in Italy. The artist used clear contours to define the unfolding mountain ridges, which are stacked in colored tiers, thereby communicating an expansive recession away from the viewer toward distant snowcapped peaks. The sheet is part of a group of watercolors and paintings based on the sketches that Oehme made during the trip. The finished works focus on the austerity and vastness of the Alpine terrain, omitting all references to the tourism industry that flourished in the region at the time.

Ernst Ferdinand Oehme

German, 1797–1855

The Rigi, 1825

Pen and gray and brown ink and watercolor with white opaque watercolor

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1908-1257

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Andreas Diesend