Observation and Fantasy, 1600–1750

Drawing in this period is characterized by the productive tension between the close observation of natural phenomena and an exuberant, unconstrained play of imagination. On the one hand, artists continued to deeply engage with subjects from the Christian tradition and ancient mythology, constructing complex narrative compositions and often imbuing them with an intense emotional charge. On the other, they looked closely at the world around them, producing acutely observed and confidently rendered studies. Portraiture—and especially self-portraiture—gained renewed importance, as seen here in works by Carlo Maratti and Anton Raphael Mengs. Made thirty years apart, two drawings by Rembrandt represent the Kupferstich-Kabinett’s rich historic collection of works by the innovative Dutch artist, as well as his students and associates.

Jan Harmensz. Muller

Like many other artists active in central and northern Europe at the end of the sixteenth century, Muller had a liking for subjects both erotic and esoteric. This drawing focuses on a littleknown passage from Homer’s Odyssey, featuring the brief and tragic love affair between Demeter, the Greek goddess of agriculture—known as Ceres in Roman mythology—and the young hero Iasion. Here, the artist depicts the moment when the lovers are discovered by Jupiter. As the canopy hanging over the bed flies open, vivid rays of light, emanating from Jupiter, illuminate their entangled bodies. The figures’ oversize limbs and contorted poses, delineated using pen lines that swell and break with a nervous rhythm, are typical of Muller’s early draftsmanship.

Jan Harmensz. Muller

Netherlandish, 1571–1628

Ceres and Iasion Discovered by Jupiter, ca. 1589–90

Pen and black ink, brush and brown wash, heightened with white, partially incised, on reddish prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 888

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Rembrandt van Rijn

In this drawing, Zeus (known as Jupiter in Roman mythology), disguised as an eagle, abducts Ganymede, a young Greek hero hailing from the city of Troy. Although Ganymede was admired for his unmatched beauty and often depicted in an erotically charged manner, Rembrandt characterizes him as a frightened, unruly toddler who squirms and screams as Zeus carries him away. The artist’s exuberant marks range from bold, zigzagging lines, which delineate the eagle’s body, to the loose swirls on the right side of the composition, which do not seem to serve a specific descriptive function. The drawing was used as a preparatory study for Rembrandt’s painting The Abduction of Ganymede, which is also part of the Dresden collection.

Rembrandt van Rijn

Dutch, 1606–1669

The Abduction of Ganymede, ca. 1635

Pen and brush and brown ink

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1357

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Austeja Mackelaite, Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator of Drawings and Prints

In the mid-1630s, the young Rembrandt enjoyed a high point in his career. He had recently moved from his native Leiden to Amsterdam, where he joined the local painters’ guild and began to practice as an independent master. Drawings from this period exhibit dynamism, bravura, and freshness of observation. As we look closely, we are able to witness Rembrandt’s imagination at work by tracing the quick movements of his hand.

In this sheet, the artist took up a story from Greek mythology. As Homer described in his Illiad, written in the eighth century BC, Zeus—the chief deity in the Greek pantheon—fell in love with the young Trojan youth, named Ganymede. Here, Rembrandt imagines the culmination of the story’s dramatic arc. He shows Zeus, who has turned himself into an eagle, abducting Ganymede from Mount Ida near Troy and getting ready to carry him to Mount Olympus, the home of the gods.

While artists have traditionally represented Ganymede as an adolescent, Rembrandt depicts him as a fussy toddler being separated from his parents—the two figures with their arms up, roughly sketched at lower left corner. His pen and brush move quickly across the sheet, filling the space with a variety of marks—from fine and deliberate strokes, which describe child’s grimace of desperation, to extremely loose, non-descriptive, squiggly lines, which might evoke gusts or currents of air.

Rembrandt van Rijn

Made three decades after The Abduction of Ganymede, on view nearby, Diana and Actaeon exemplifies the reduced, angular manner of drawing that Rembrandt developed in his late works. At left, Diana, the Roman goddess of the hunt, is bathing in the company of her nymphs. The group is observed by the young mortal Actaeon, who stands on an elevated bank at right, behind a large tree trunk. As described by the Roman poet Ovid, Diana punishes Actaeon’s voyeurism by transforming him into a stag. In this sheet, Rembrandt simultaneously portrays the moment when the goddess realizes that she has been observed and the subsequent punishment, showing Actaeon as part human and part animal, with his face transformed into a muzzle and antlers sprouting from his head.

Rembrandt van Rijn

Dutch, 1606–1669

Diana and Actaeon, 1663–65

Pen and brush and brown ink, with traces of white opaque watercolor

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1384

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Jan Lievens

This sheet belongs to a group of large-scale, highly finished drawings that Lievens created in the early years of his career. It focuses on the suspenseful banquet that Esther, an Old Testament heroine, prepared for her husband, the Persian king Ahasuerus, and his vizier, Haman. With her gaze fixed on Ahasuerus, Esther gestures emphatically toward Haman, who had been secretly plotting to annihilate the Jewish people. As his vicious plan is being uncovered, Haman crouches in his chair, his face submerged in the shadows. The drama of the event is enhanced by Lievens’s bold use of chiaroscuro effects and his decision to position the figures in the middle ground, with a curtain framing the composition at left, which effectively transforms the scene into a stage.

Jan Lievens

Dutch, 1607–1674

The Feast of Esther, ca. 1628

Brush and black and gray ink, gray and brown wash, heightened with white, over black chalk, with traces of red chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1980-463

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

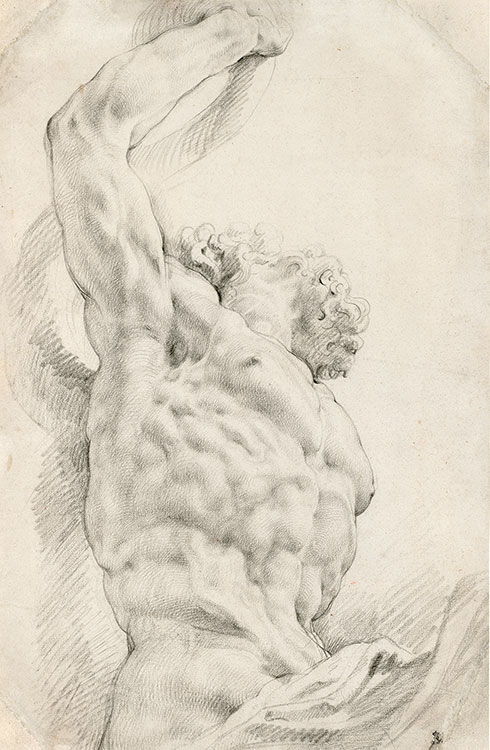

Peter Paul Rubens

During his two visits to Rome, Rubens studied the Laocoön (shown below) more intently than any other ancient statue. The chilling depiction of the anguished Trojan priest, struggling to release himself from the tight coils of the snakes that threaten to suffocate him and his two children, provided the artist with an opportunity to observe a male body engaged in an intense physical struggle. Rubens created a dense, pulsating network of lines, methodically capturing the tense muscles and protruding veins of Laocoön’s torso and right arm in black chalk. The sculpture is observed from below and sideways, exemplifying the artist’s interest in finding unusual and dynamic viewpoints when drawing ancient sculpture.

Peter Paul Rubens

Flemish, 1577–1640

Torso of Laocoön, ca. 1601–2

Black chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1874-22A

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Peter Candid

Born in the Netherlands, Candid spent most of his early life in Florence, where he was active as a painter and tapestry designer. In 1586, he moved to Munich, joining the cohort of international artists working for Wilhelm V, Duke of Bavaria. This drawing served as a preparatory study for a print commemorating the foremost architectural project in the city at this time—the construction and decoration of Saint Michael’s Church. It reproduces one of the building’s principal façade elements, a large bronze sculpture representing the archangel Michael defeating the devil. Composed of layers of delicate gray wash and dense areas of hatching, the drawing successfully conveys both the sculpture’s intricate surface detail and its overall monumental effect.

Peter Candid

Netherlandish, 1548–1628

The Archangel Michael Defeating the Devil, ca. 1597

Black chalk, pen and brown ink, brush and gray wash, heightened with white, traces of red chalk, incised, on light-brown prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 885

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Tanzio da Varallo

This sensitive drawing, which depicts an angel leading the soul of a deceased man to heaven, was made by Tanzio in preparation for his fresco decorations in the Chapel of the Guardian Angel in the Basilica of San Gaudenzio, Novara, completed in 1629. The drawing corresponds closely with two figures painted in the chapel, who glide aloft on clouds at the base of the vault. The angel guides the deceased with his right hand and gestures with his left, directing his charge to look up toward the vault’s apex, where Christ appears. Tanzio’s finished study focuses on this moment of divine revelation, delicately rendering the interplay of light and shadow across the figures.

Tanzio da Varallo

Italian, ca. 1582–1632/33

An Angel Guides a Deceased Believer to the Kingdom of Heaven, ca. 1628–29

Red chalk on reddish prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1937-840

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Hendrick Goltzius

Characterized by a strong sense of immediacy, this drawing was likely based on a life study. Goltzius outlined the contours of the figure’s headdress and face using swift, sharp strokes of red chalk, and skillfully described the soft surface of the skin by rubbing powdery red pigment with a finger or stump. Despite the drawing’s compelling naturalism, the identity of the subject remains unclear. While scholars have traditionally referred to the figure as an older woman, the thick neck with the Adam’s apple protruding right below the chin, the unruly short hair playfully sticking out from underneath the headdress, and the overall lack of idealization suggest that the subject may be a male figure in a chaperon, a type of headwear popular in the Middle Ages.

Hendrick Goltzius

Netherlandish, 1558–1617

Head Study, ca. 1605–10

Red chalk, incised

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 897.

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Sofonisba Anguissola

Anguissola was born to a noble northern Italian family and, together with her six siblings, received a comprehensive humanistic education and training in the art of painting. Perhaps because her gender precluded her from studying anatomy or working with nude models, she focused on portraiture, often turning to sitters in her familial and social circles. This study, which might be a self-portrait, is an example of the artist’s direct yet sensitive approach to the portrait genre and her assured drawing technique. Although Anguissola’s drawing skill was praised by her contemporaries, extremely few sheets by the artist survive today.

Sofonisba Anguissola

Italian, ca. 1535–1625

Portrait of a Lady with a Feathered Hat (Possibly a Self-Portrait), ca. 1575–1600

Black chalk on gray-blue paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1937-785

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator and Department Head

Sofonisba Anguissola was the most famous woman artist of the Italian Renaissance. She was born in Cremona, Italy, and was trained as a painter by Bernardino Campi, the leading artist in that city, but she also received a humanist education. Her fame as a painter quickly spread, not only in Italy but across Europe, and in 1559 she was invited to Spain to serve as a lady-in-waiting to the queen. While in Spain, she painted many portraits of the royal family and other members of court. She spent more than a decade in Madrid before marrying a Sicilian nobleman and returning to Italy.

Relatively few drawings by Sofonisba survive, but the Dresden sheet agrees in style with the few secure examples, and the early inscription at the bottom of the sheet also attributes it to her. It could in fact be an image of the artist herself. Sofonisba painted a series of self-portraits, more than any woman before her time, and the shape of the face, the almond-shaped eyes, and the slightly pointed ears of the woman in this drawing resemble those in the paintings, as does her sidewards but direct gaze. The open-necked dress and feathered hat would have been unacceptable at the Spanish court, however, so this drawing was probably made either just before her departure from Italy, or else just after her return.

Antoine Watteau

Study with Four Pilgrims and a Cupid relates to Watteau’s painting The Embarkation for Cythera. He first depicted the subject around 1709–12 and returned to it a few years later, producing two variations. In these convivial works, groups of elegantly dressed young people mingle in bucolic settings as they prepare to embark for the Greek island that was, according to classical legend, the birthplace of Aphrodite, the goddess of love. In 1717, the French Academy described Watteau’s Embarkation for Cythera as a fête galante, giving a name to the genre that would become the artist’s signature development. In this drawing, Watteau adeptly varied the pressure of the red chalk to define the fashionable characters.

Antoine Watteau

French, 1684–1721

Study with Four Pilgrims and a Cupid, ca. 1709–12(?)

Red chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 734

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

The term fete galante, used to describe a group of men and women in elegant dress at leisure in the landscape, came into use around 1700 and in fact such scenes of outdoor romance already were gaining currency in theatrical productions of the 1690s. Nevertheless, Watteau’s evocation of Cythera in the canvas at the Louvre remains the most poetic and memorable example of the genre.

Watteau spent the majority of his career outside the official French academy. He drew incessantly, making studies and carrying them in a portfolio, turning to this repository when he needed figures for paintings. The separate studies scattered across this page, with their mix of orientation and scale, reveal Watteau’s process of compiling individual motifs rather than devising a composition first and then methodically making studies of each figure in it. The male figure wearing the theatrical costume of a stylish follower of Venus is drawn three times on the sheet in different poses, and appears in a few versions of the painted composition while the female devotee at center—who seems as if she’s the main study on the sheet—was not used in a painting. As your eye roves across the page, the individual studies reveal several moments of creation that eventually contributed to one of the most celebrated paintings in Western art.

Anton Raphael Mengs

Considered one of the pioneers and most important representatives of Neoclassicism, Anton Raphael Mengs began his training as a child under his father, the Saxon court painter Ismael Mengs. Anton Raphael graduated from this early, intensive tutelage around 1740, when he was twelve years old—the same year that Ismael and his children began a fouryear stay in Italy to continue their artistic education. This remarkable self-portrait, the earliest to survive by Anton Raphael, was drawn in that year, before the family’s move. A testament to the artist’s precocious talent, the drawing sensitively blends the black and red chalk to create a lifelike record of the young Mengs’s features as studied in a mirror.

Anton Raphael Mengs

German, 1728–1779

Self-Portrait at Twelve Years Old, 1740

Black and red chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 2464

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

What did it mean in 1740 to be a twelve year old draftsman capable of wielding colored chalks to capture your own likeness? This self-portrait is an unusually accomplished piece of juvenilia, and rarely do we have datable works for this early stage of an artist’s career. The German tradition, however, is curiously strong in such works: among the most memorable being a striking self-portrait executed in 1484 by a 13 year old Albrecht Durer. At the time Mengs executed this sheet, he was under his father’s tutelage and transitioning from making copies to drawing from life. We see one of his first forays into drawing aided with a mirror, as he uses himself as the model. An old slip of paper once attached to the back of the drawing notes that Mengs gave the sheet to a classmate before the artist and his family departed for Italy. This practice of giving and exchanging drawings would flourish among young German artists in the nineteenth century.

Carlo Maratti

In this large and commanding self-portrait, Maratti, one of the leading protagonists of the Roman Baroque, represents himself at about the age of sixty, when he was at the height of his artistic influence. In a virtuosic display, the artist elaborated his features and the fall of light with a meticulous network of cross-hatching using a sharp piece of red chalk. The drawing was not made in preparation for a painting but is instead an autonomous work of art, serving as both a record of Maratti’s likeness and a potent demonstration of his artistic abilities.

Carlo Maratti

Italian, 1625–1713

Self-Portrait, ca. 1680–85

Red chalk (in two shades)

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 243

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator and Department Head

Carlo Maratti was from the late seventeenth century until his death in 1713 one of the leading artists in Rome, the heir to a classicizing tradition that began with Raphael and extended through the work of Annibale Carracci. He received the most traditional of Italian artistic educations, being made to master draftsmanship before turning to painting, and to engage in extensive life drawing as well as copying classical sculpture and paintings of the great masters. Hundreds of surviving drawings by him demonstrate that draftsmanship remained essential to his art throughout his career… and his remarkable abilities as a draftsman can be seen in this sheet. It is one of series of self-portrait drawings that Maratti made in the early 1680s, when he was at the height of his powers and was the head of the largest, most important painting workshop in Rome.

Maratti’s painted portraits are often somewhat idealized, and they often include elaborate draperies and props that indicate the sitter’s occupation or status, but his portrait drawings – especially the self-portraits – instead reflect his ability to observe and capture appearances and personalities. Especially in a large sheet like this, we marvel at Maratti’s vitality and presence, emphasized by his gaze directly out at the viewer, even as we also appreciate his remarkable facility to evoke the textures of flesh, hair, and fabric in his preferred medium of red chalk.

Francisco de Goya

A group of monks, identified by their habits, pore over an open book; uneven light flickers across the scene, deftly rendered with brush and wash. The relationship and significance of the older man and younger woman standing together behind the main group, seemingly uninterested in seeing the volume, are ambiguous. The caricature-like faces and coarse delight of the three monks in the foreground imply that their book is not devotional and announce the drawing’s satirical nature. This sheet comes from one of several private albums that Goya compiled throughout his career. As in many of his published prints, the imagery in these drawings is replete with social criticism directed at the clergy, among others.

Francisco de Goya

Spanish, 1746–1828

Monks Reading, ca. 1812–20

Brush and brown wash

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1910-56

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator and Department Head

Francisco de Goya is best known for his paintings and his remarkable etchings, but he made some of his most personal and mysterious works in the drawing sketchbooks and albums that remained in his possession until his death. This was especially true late in his life, when a mysterious illness had left him deaf, and the Napoleonic wars had ended his close association with the Spanish court. The aging artist turned inward, producing scores of drawings like this work, and others that include satirical and cynical looks at contemporary life, alongside scenes of war, savagery, and witchcraft.

This sheet comes from an album that originally contained around 90 densely worked drawings made on writing paper with a brush and a corrosive brown ink, materials presumably adopted because of of good drawing paper and ink were not readily available during the war. In contrast to many of Goya’s drawings, those in this album generally do not have captions, and so they remain open to interpretation. Here, we see a group of seated monks in the foreground, but their coarse expressions suggest that their reading is something other than sacred literature. Behind them stand a woman, who seems to be hiding herself from the leering monks, and an older, apparently toothless monk looking upward, perhaps embarrassed by his companions or else because of his great age no longer interested in their activities.

Portrait of Muhammad ‘Ādil Shāh

This album, containing dozens of portraits by several artists of rulers and noblemen from the Mughal Empire and the Deccan, was in the possession of the Dresden court by the end of the seventeenth century. Following a traditional representational style, these two portraits show Muhammad ‘Ādil Shāh, Sultan of Bijapur, at right, and Ikhlās Khān, his military commander and influential minister, at left. Often copied from earlier depictions, the subjects of the album’s portraits are identified by specific physical characteristics and attributes such as attire and weapons, though the artists expressed their individuality by introducing subtle variations. In the right-hand portrait, the unknown artist’s creativity and skill are especially evident in the depiction of the transparent muslin skirt.

Unknown artist

India (Deccan sultanates, Golconda)

Muhammad ‘Ādil Shāh, Sultan of Bijapur (r. 1627–56) (right) and Ikhlās Khān (d. 1656) (left), 1668–89

Opaque watercolor and gold; frame: gold, framing lines in black ink, on a ground flecked with green watercolor

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NOS. CA 112/7 AND CA 112/8

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Austeja Mackelaite, Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator of Drawings and Prints

The Kupferstich-Kabinett holds a small but important collection of Indian miniature paintings from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Some of the works—including this seventeenth-century volume—entered the collection shortly after they were made. An inscription inside the book proves that it was in German possession by 1689 at the latest—an unusually early date. It probably reached Germany via Amsterdam, through the Dutch East India Company, which dominated European trade with Asia at this time.

The book includes depictions of rulers associated with four Indian dynasties. The subjects are identified in inscriptions at the center of each sheet; they are also recognizable through specific physical characteristics, attire, and weapons, as well as other attributes. In the image at right, Mohammed Adil Shah, Sultan of Bijapur [Bee-zha-poor], is placed against a plain background, boldly rendered in blue opaque watercolor. He is holding a flower, as an indication of his cultivated refinement. The image at left depicts Ikhlās Khān, a formerly enslaved man of Ethiopian descent, who served as a military commander and powerful advisor to the sultan. Khan is wearing a pink tunic and a jacket decorated with flowers, and holds a sword and a shield in his hands. The two men worked closely together and were often depicted side by side, as here.

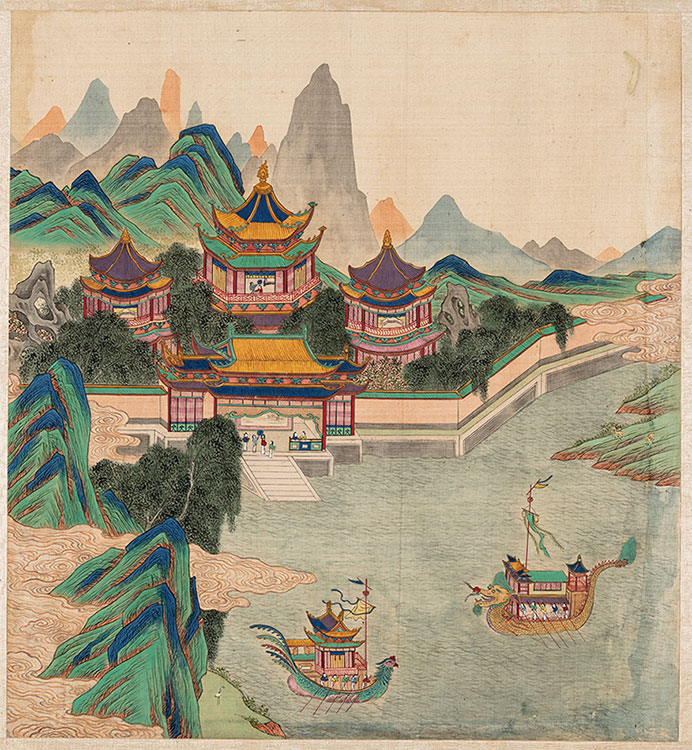

Palace Garden with Ceremonial Barques

This boldly colored depiction of two groups of women rowing ceremonial boats before a palace garden backed by mountains belongs to a genre known as xingle xt (行乐图, pictures of life at leisure). The idyllic scene was executed using the exacting Gongbi technique (工笔, Careful Brush Technique), combining meticulous brushwork, bold colors, and jiehua, the precise rendering of architecture with a traditional ruler called a jiechi (界尺). This late Ming dynasty watercolor is one of nine related landscapes in Dresden that descend from the collection of Nicolaas Witsen (1641–1717), a mayor of Amsterdam and collector of Asian art. The Kupferstich-Kabinett acquired several Chinese and Indian works from the sale of Witsen’s estate in 1728.

Unknown artist

China

Palace Garden with Ceremonial Barques, first half of the seventeenth century, late Ming dynasty

Brush and watercolor and opaque watercolor on silk, mounted on cardboard

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. CA 132/5

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Andreas Diesend

Bernardo Bellotto

In the first half of the eighteenth century, the architectural and cultural landscape of Dresden underwent a radical transformation. Focused on making the city into a major European capital, the Saxon rulers commissioned ambitious architectural projects and assembled a remarkable number of foreign artists at the court. Bellotto arrived in Dresden in 1747, bringing with him the Venetian tradition of vedute, or highly detailed topographical views. In this work, the viewer gazes from the right bank of the Elbe River toward the Augustus Bridge and the Old Town. The Dresden Castle, where the Kupferstich-Kabinett is located today, can be seen on the far right of the image, behind the newly built Dresden Cathedral. The only print included in the exhibition, this view conveys the splendor of Dresden during the decades shortly after the official establishment of the Kupferstich-Kabinett.

Bernardo Bellotto

Italian, 1722–1780

Dresden from the Right Bank of the Elbe, Below the Augustus Bridge, 1748

Etching; state I (of IV)

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. A 85857

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank