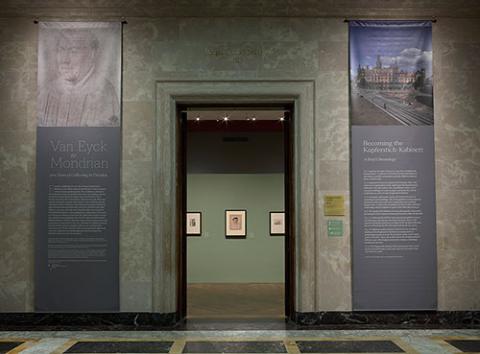

Van Eyck to Mondrian: 300 Years of Collecting in Dresden

Formally established in 1720, the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett is the oldest museum dedicated to works on paper in the German-speaking lands. This exhibition celebrates the institution’s three hundredth anniversary by bringing together around sixty of its finest drawings, many of which have never before traveled to the United States. Made between the fifteenth and the twentieth centuries, the works on view celebrate pivotal moments and key traditions in the history of European draftsmanship. Foremost among them is Jan van Eyck’s Portrait of an Older Man (ca. 1435–40)—the only surviving drawing by the renowned Netherlandish painter. Acknowledging the importance of Dresden as a European cultural center from the eighteenth century onward, the exhibition also highlights the work of Caspar David Friedrich, Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Dix, and other artists with strong personal and professional connections to the city. Although the display primarily focuses on the European graphic tradition, two refined works from India and China, acquired in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, illuminate the global approach that has shaped the Dresden collection since its inception.

Van Eyck to Mondrian: 300 Years of Collecting in Dresden was organized by the Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden and the Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

This exhibition is made possible by an anonymous donor, in memory of Melvin R. Seiden. Generous support is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Fund for Scholarly Research and Exhibitions; the Wolfgang Ratjen Foundation, Liechtenstein; The Christian Humann Foundation; Mr. and Mrs. Clement C. Moore II; Elizabeth and Jean-Marie Eveillard; Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder; and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation; with assistance from the Arnhold Family, in memory of Henry H. Arnhold.

This exhibition is also made possible with the kind support of the Consulate General of the Federal Republic of Germany, New York.

Overview

Gallery Images

Becoming the Kupferstich-Kabinett

A Brief Chronology

1560: Augustus, the ruler of Saxony (r. 1553–86), establishes the Kunstkammer—a cabinet of curiosities housing natural history specimens, scientific instruments, precious objects, sculpture, prints, and drawings.

1720: Augustus II, known as Augustus the Strong (r. 1694–1733), orders the reorganization of the rapidly growing Kunstkammer collection. The edict leads to the consolidation of the court’s extensive holdings of works on paper and marks the official establishment of the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett.

1728: During the eighteenth century, the museum focuses on expanding its print holdings. The 1728 acquisition of more than ten thousand works collected by the Leipzig alderman Gottfried Wagner (1652–1725) lays the foundation for the Dresden collection of drawings, which continues to grow in the following centuries.

1898: The Kupferstich-Kabinett sets up a photography department, becoming the first German art museum to actively collect in this field.

1919–33: Following World War I, the museum intensifies its focus on collecting contemporary drawings and prints. Many works acquired during this period are no longer in the Dresden collection due to confiscations by the Nazi regime during the late 1930s.

1942: As fighting escalates during World War II, the complete holdings of the Kupferstich-Kabinett are transported to a safekeeping repository at the Weesenstein Castle, twelve miles south of Dresden. There, the works survive the bombing raids of February 1945, which largely destroy the complex of buildings housing the museum.

2004: The Kupferstich-Kabinett finds a permanent home at the newly restored Dresden

Drawing in the Renaissance

Starting in the fifteenth century, drawing came to be understood as a fundamental creative act. In Italy, it was increasingly viewed as an intellectual activity, closely aligned with the process of pictorial invention. Although surviving in significantly smaller numbers, drawings made in northern Europe also exhibit a growing emphasis on invention and observation, catalyzed by a close study of the natural world. A number of sheets on view here—by Jan van Eyck, Andrea del Verrocchio, Matthias Grünewald, and Correggio—served as preparatory studies for paintings, attesting to drawing’s central role in the conception and execution of other works of art. Other compositions, such Urs Graf’s prominently monogrammed Farewell, speak to the taste for more finished autonomous drawings that emerged at this time. The culture of collecting drawings went hand in hand with these developments. While most works in this section became part of the Dresden collection in the eighteenth century or later, the vibrant nature studies by Lucas Cranach the Elder and his workshop were likely acquired not long after the artist’s death, probably entering the electoral Kunstkammer at the end of the sixteenth century.

Jan van Eyck

Van Eyck’s Portrait of an Older Man is a benchmark in the history of northern European draftsmanship. It is the earliest surviving study that can be securely attributed to an individual artist active in northern Europe and the only sheet universally accepted as an autograph drawing by Van Eyck. A pivotal figure in Netherlandish art, Van Eyck is renowned for his virtuosic handling of oil paint and his skill in pictorial illusionism. Made in preparation for a painted portrait (shown below), this drawing illuminates the process of careful observation behind the creation of Van Eyck’s meticulously executed panel.

The artist focused his attention on the man’s face, which he modeled using densely packed parallel lines. He was particularly concerned with the play of light, which animates the sitter’s physiognomy and imbues the likeness with a sculptural quality. While the use of silverpoint and goldpoint—traditional fifteenth-century drawing media—resulted in a monochromatic image, extensive inscriptions to the left of the man’s head vividly describe the color of his eyes, lips (“very whitish purple”), skin tone, hair, and “stubbly beard.” Van Eyck would have referred to these notes when creating the painted portrait.

Although both the drawing and painting were long believed to depict Niccolò Albergati, a Carthusian monk from Bologna, the man’s secular dress and hair argue against such an identification. More likely, the sitter is a scholar whose name is no longer known to us.

Jan van Eyck

Netherlandish, 1390–1441

Portrait of an Older Man, ca. 1435–40

Silverpoint and goldpoint on white prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 775

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Austeja Mackelaite, Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator of Drawings and Prints

Jan van Eyck was the most famous and accomplished member of the family of fifteenth-century painters hailing from the town of Maaseick, in modern-day Belgium. Employment at the courts of Holland and Burgundy secured him a high social status, unusual for artists of the time. Van Eyck’s supreme skill in working with the medium of oil paint paved the way for a new visual aesthetic, which characterized Netherlandish painting during the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.

While approximately twenty paintings by Van Eyck have survived to our day, a single drawing—the Dresden sheet, in front of you—has been securely attributed to the artist. The attribution was established in the first half of the nineteenth century, on the basis of a close relationship between the drawing and a painted portrait in Vienna, also by Van Eyck, depicting the same male sitter. The Dresden sheet evidently served as a preparatory study for the Vienna work.

When I look at the drawing, I am struck by how closely Van Eyck studied his sitter, concerned with conveying the topography of the older man’s face—from the soft wrinkles around his eyes and lips, to his high cheekbones, and a square, defined chin. He was also clearly interested in the three-dimensional quality of the head, carefully transcribing the patterns of light and dark on the man’s skin, and applying intense shading outside the contours of the face. The identity of the sitter and the circumstances of the sheet’s commission remain unknown to us. Nevertheless, the somber figure—and the drawing itself—are imbued with an unmistakable power and presence.

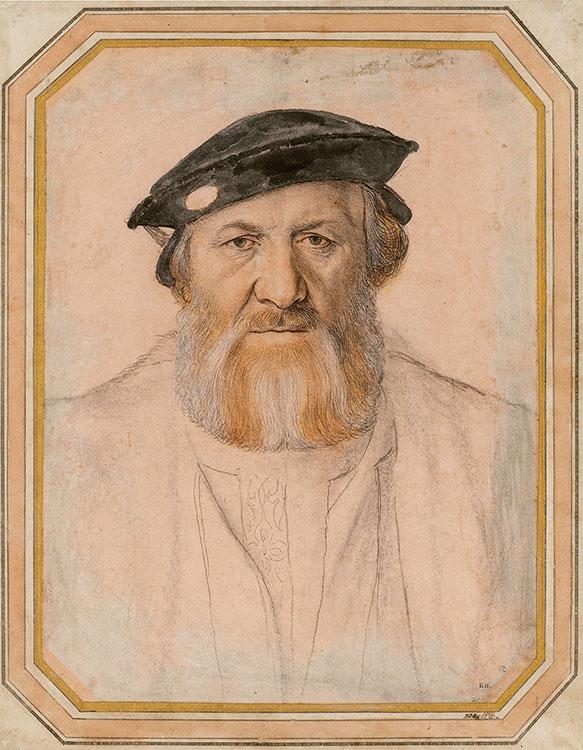

Hans Holbein the Younger

Born in Germany and first active as an independent master in Switzerland, Holbein spent the final decade of his life in England, working in the ambit of the Tudor court. He was particularly admired for his skills as a portraitist. This imposing likeness of Charles de Solier—a French nobleman, soldier, and diplomat—exemplifies the multilayered drawing technique that Holbein developed for his portrait studies around this time. The artist used paper prepared with a light-pink ground, approximating his sitter’s skin tone. Subtle modeling in black and colored chalk helped animate the frontal likeness, drawing the viewer’s attention to Solier’s pensive gaze. Perhaps most striking, however, is Holbein’s meticulous rendering of the man’s beard, composed of gray and auburn streaks.

Hans Holbein the Younger

German, 1497/98–1543

Portrait of Charles de Solier, Comte de Morette, 1534–35

Black and colored chalk, pen and brown ink, black wash, and white opaque watercolor on pink prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1977-156

Austeja Mackelaite, Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator of Drawings and Prints

The man gazing directly at us from this image is Charles de Solier, French soldier and diplomat, who acted as French ambassador to England on a number of occasions from 1526 to 1535. We know that he stayed in London from April 1534 to July of the following year, which is when he commissioned Hans Holbein the Younger to make this portrait. The artist started as he always did—by making a detailed and strikingly naturalistic study of the man’s face. He used a wide range of drawing media at his disposal—black and colored chalks, black ink and wash, and white opaque watercolor, all layered to achieve uncannily realistic effects. While the finished painted portrait is dominated by the sumptuous clothes and jewelry worn by the sitter, in the drawn study, the clothing is only suggested with a few lines of black chalk.

The drawing was acquired by the Dresden museum shortly after it was auctioned in London in 1860 as part of the collection of Samuel Woodburn, English art dealer. One of the reasons for the purchase was the desire to reunite the drawing with the finished painted portrait of de Solier, which had entered the Dresden collection more than a century earlier. The painting and the drawing hung side by side in the Dresden Picture Gallery for many decades that followed, inviting visitors to compare Holbein’s work in these two different media.

Matthias Grünewald

Grünewald conceived this boldly rendered and expressively foreshortened figure as a witness to one of the key New Testament miracles—the Transfiguration. In this biblical event, Christ is enveloped in a halo of light as his divine nature is revealed to a small group of apostles. Here, one of the apostles is depicted as having tumbled to the ground, his body contorted and his arms extended forward, as though to protect himself from the blinding apparition. Grünewald used this study to explore the direction and modulation of light, which illuminates the apostle’s back, creating a stark contrast with the rest of the heavily shaded drapery.

Matthias Grünewald

German, ca. 1480–1528

Study for an Apostle (James or John) in the Frankfurt Transfiguration, ca. 1510–11

Charcoal, fixed, partially heightened with white

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1910-42

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Urs Graf

In addition to his activities as a draftsman, engraver, and goldsmith, Graf was a mercenary who participated in military campaigns in Italy and France. Many of his drawings build on these experiences, chronicling the life of soldiers and the vicissitudes of war. In this sheet, a soldier and a woman are seen parting ways. While she firmly grips the front of his cloak, a sword in his left hand connects with her bulging belly, imbuing the drawing with an erotic charge. The scabbard points into the dark landscape at right, indicating the departing soldier’s direction. Although Graf’s highly linear style evokes printmaking, the drawing was not a preparatory study for an engraving. Monogrammed and dated at lower right, it was created as an independent work of art.

Urs Graf

Swiss, ca. 1485–1527/28

The Farewell, 1513 or 1515

Pen and black ink

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1899-42

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

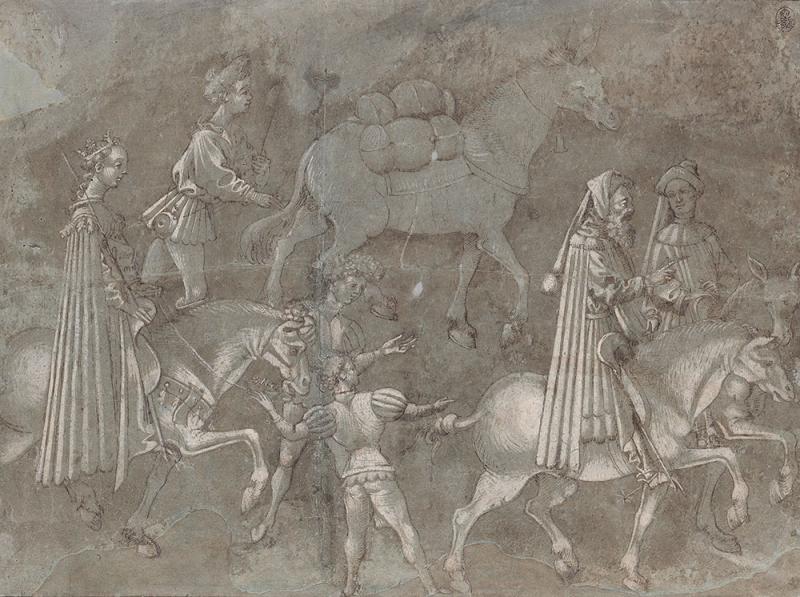

Giovanni da Modena

In a procession organized in two tiers, a princess on horseback is accompanied by servants and led by a bearded rider who points the way to a younger companion. Courtly cavalcades were popular motifs in fifteenth-century Italy, but women seldom played a leading role in such scenes, and the subject of this intriguing composition remains elusive. The artist drew attention to the now-mysterious princess and the bearded rider through both their placement in the composition and their attentively rendered robes and horses, heightened in white to contrast with the paper’s midtone. The drawing is one of the oldest surviving works on manufactured blue paper.

Giovanni da Modena

Italian, ca. 1379–1454/55

Riding Procession with a Princess, Two Men, and Pages, ca. 1410–50

Pen and brown ink, brush and brown wash, heightened with white, over traces of black chalk on blue paper; partially pricked for transfer

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 150

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Unknown Burgundian artist

This finely executed drawing depicts Jupiter, the mythical Roman god, identified by the lightning bolts in his right hand, the eagle appearing over his left shoulder, and the fallen Titan partially visible beneath the god’s ornate robes. Jupiter here symbolically represents his eponymous planet, as the inscription around the five-pointed star at lower center indicates. On the verso of this sheet, the unidentified Burgundian artist portrayed Venus. Further drawings in Dresden by the same hand feature Mercury, Mars, and Saturn, the gods corresponding with the other planets then known. The style of the drawings and the figure types employed suggest a dating of around 1420–30, a notably early date for a drawing of this type.

Unknown Burgundian artist

The Planet Jupiter (recto) and The Planet Venus (verso), ca. 1420–30

Pen and brown ink

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 579

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Andrea del Verrocchio

A much-celebrated example of Florentine draftsmanship of the fifteenth century, Verrocchio’s Madonna with the Brooch demonstrates a range of techniques and artistic interests. The artist first sketched the Virgin and Christ Child in silverpoint, establishing the composition with a light touch and making several small adjustments in the process. Focusing his attention on the Virgin, he used leadpoint to reinforce contours and adjust the figure’s eyes, neck, and brooch. Picking up the brush, Verrocchio then skillfully described the fall of light over the Virgin’s robes, adding brown wash for shadows and opaque white watercolor for highlights. These painterly passages add a convincing sense of plasticity and volume to the more immediate and spontaneous metalpoint sketch.

Andrea del Verrocchio

Italian, 1435–1488

Madonna with the Brooch, ca. 1470–74

Silverpoint and leadpoint with light-brown wash, heightened with white, on light-gray prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 32

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator and Department Head

Andrea del Verrocchio is best known to most people today as having been the teacher of Leonardo da Vinci, but he was in his own right one of the most influential and versatile artists working in fifteenth-century Italy. He was a sculptor, a painter, and an exquisite draftsman. This densely worked sheet attests to his powers in the medium. It began as a quick sketch in silverpoint, in which the artist laid out the composition of the Madonna and child. He then used a second metal stylus, probably leadpoint, to refine the details of the Virgin’s face, dress, and jewel, leaving the Christ child as a little more than a sketchy outline. Ultimately, however, the purpose of this drawing was to study the volumes of the Madonna’s drapery, and to that end Verrocchio used brown wash and white heightening to bring the fabric into high relief. Finally, he added further hatching to deepen the shadows and enhance the sharp chiaroscuro.

The sheet was probably made in the early 1470s as a preparatory study for a relatively small-scale devotional painting, but the power of the drawing was such that it remained in the workshop and served as the basis for at least seven different paintings by Verrocchio and his pupils. This is, in fact, precisely the sort of work by Verrocchio that would have inspired Leonardo, and it is little surprise that the study was long believed to be by Leonardo himself rather than his master.

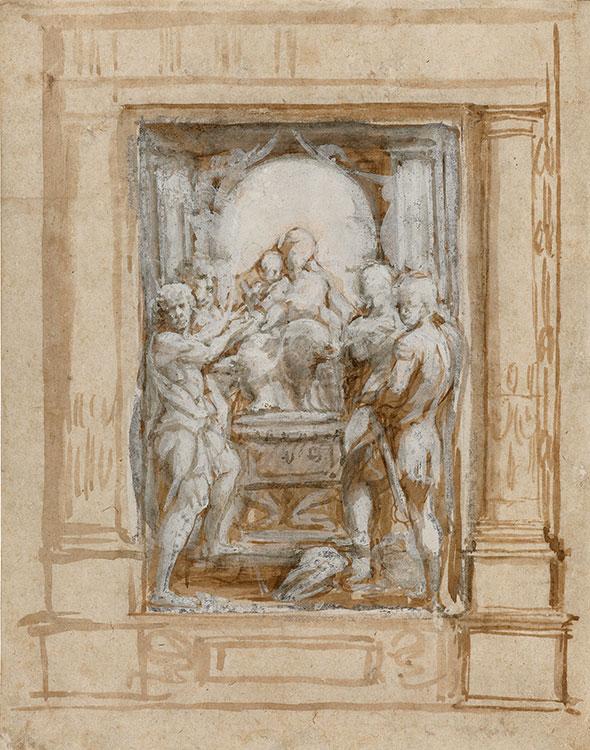

Correggio

Remarkable in its fluidity and freedom, this drawing served as a preparatory study for an altarpiece (shown below) commissioned by the brotherhood of Saint Peter Martyr in the northern Italian town of Modena. Correggio began by laying out the basic composition in chalk or charcoal, which he then extensively reworked using brown wash and white heightening. Such bold, painterly use of the drawing media allowed the artist to effectively describe the plasticity and movement of his figures, and to explore the effects of light. The study was acquired by the Kupferstich-Kabinett in 1860 as a complement to the finished painting, which entered the Dresden collection in 1746.

Antonio Allegri, known as Correggio

Italian, ca. 1484–1534

Madonna di San Giorgio, before 1530

Brush (and pen?) and brown ink and brown wash, heightened with white, over traces of black chalk or charcoal

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 367

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator and Department Head

Correggio’s Madonna of Saint George altarpiece was painted around 1530 for a small confraternity church in Modena, Italy, but the work quickly became famous, celebrated for the intricacy of its composition and its sophisticated approach to light. By the seventeenth century, the Dukes of Modena had acquired the painting, and they sold it to Frederick Augustus II of Dresden in 1746. It was thereafter considered one of the masterpieces of the Dresden collection. Accordingly, when Correggio’s compositional drawing for the altarpiece came up for sale in London a century later, in 1860, the Kupferstich-Kabinett eagerly sought it, and celebrated it as a major acquisition.

In the drawing, we can see Correggio working out both the composition and the lighting scheme. He began work by sketching out the frame he envisioned for the painting, and then took up chalk or charcoal for an initial sketch of the figural composition. It shows the Madonna and child enthroned at center, with Saints John the Baptist, Gimignano (the patron saint of Modena), Peter Martyr, and George. Only traces of this initial chalk drawing can be seen, however, for Correggio worked and reworked the drawing, adding layers of wash and especially of white opaque watercolor, emphasizing the highlights and giving a painterly plasticity to the figures. The composition already seems worked out in the drawing, but in the final painting, Correggio enlivened it further, adding a group of playful putti and giving the saints and Christ child more dramatically expressive poses.

Agnolo Bronzino

This refined drawing was most likely a preparatory study for Bronzino’s fresco decorations in the private chapel of Duchess Eleonora di Toledo at the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. The artist modeled the child’s face with delicate hatching, which he then rubbed to create finely blended shadows, endowing the study with the smooth surface of polished sculpture. The inclusion of lightly sketched wings indicates that the figure is an angel or a putto, of a similar type to those painted in Eleonora’s chapel. The seemingly abstract vertical lines on the child’s face and chest are remnants of a linear sketch of crossed legs, which relates to another figural motif developed for the chapel commission.

Agnolo Bronzino

Italian, 1503–1572

Head of a Child Looking Upward, early 1540s

Black chalk with stumping

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 85

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Lucas Cranach the Elder

In this early example of the still-life genre, Cranach captured the texture and nuanced color of the partridges’ plumage, ranging from the delicate gray tufts covering the chest to the firmer, darker wing feathers. While the dead birds are rendered against a plain background, the carefully modulated shadows create an illusionistic impression of space. Despite the partridges’ uncanny physicality and the work’s high degree of finish, the drawing was not conceived as an autonomous work of art. Like Young Stag, on view nearby, it belongs to a portfolio of drawings of animals and birds used as models for paintings in the Cranach workshop.

Lucas Cranach the Elder

German, 1472–1553

Two Dead Partridges, ca. 1530–35

Brush and gray wash, and watercolor and opaque watercolor, heightened with white

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1195

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Ian Hicks, Moore Curatorial Fellow

In 1504, Duke Frederick the Wise appointed Lucas Cranach the Elder as court artist at Wittenberg, the electoral capital of Saxony. Soon after, Cranach began building a workshop full of assistants and pupils to help him decorate the Saxon palaces and produce a steady stream of portraits over the ensuing decades. This carefully executed watercolour of two dead partridges is an early example of still-life, a genre often credited to Jacopo de’ Barbari, Cranach’s predecessor at the Saxon court. An earlier watercolour of a dead partridge by Jacopo survives and may well have inspired Cranach’s work.

The artist began this study with a preliminary drawing in brush and light grey wash. He then developed the work with a combination of dilute and opaque watercolours to describe the colour and varied textures of the partridges’ feathers. Like Cranach’s watercolour of a young stag hanging nearby, the sheet belonged to a collection of studies of birds and animals that were kept in the artist’s workshop and used as models for paintings and prints. Similar pairs of dead partridges hang in the background of several paintings by Cranach and his workshop from the 1530s that depict an episode from the Life of Hercules. The scene illustrates the demigod’s forced servitude to Queen Omphale and shows him surrounded by courtly women. Partridges were known since antiquity as a symbol of lust and served to heighten the paintings’ erotic implications.

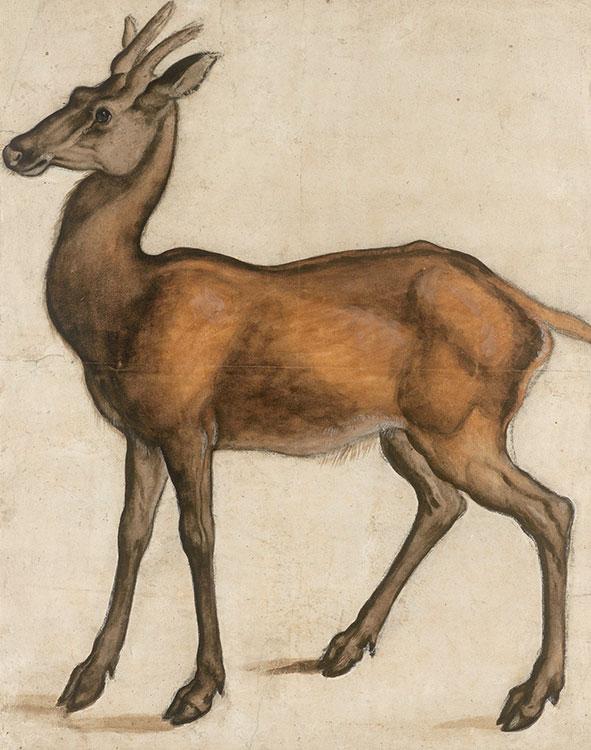

Lucas Cranach the Younger

The stag in this drawing is a pricket—a male deer in its second year with short, unbranched antlers. In contrast to Two Dead Partridges, on view nearby, the animal was likely drawn from a live model, which allowed the artist to capture its taut, welldefined muscles and other anatomic features in great detail. The stag’s alert, slightly retreating posture and circumspect facial expression have also been convincingly described. Cranach the Elder and members of his workshop would have referred to such studies when painting their hunt scenes, which were celebrated for their high degree of naturalism. In a tribute written in 1509, humanist Christopher Scheurl claimed that the artist’s painted stags were so realistic that birds fell to the ground when trying to land on the antlers.

Lucas Cranach the Elder

German, 1472–1553

or Lucas Cranach the Younger

German, 1515–1586

Young Stag, ca. 1530–65

Watercolor over chalk or charcoal, heightened with white, outline partially reworked with white opaque watercolor

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1960-32

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Zacharias Wehme

The relationship between the European powers and the Ottoman Empire in the Renaissance was marked by military conflict as well as sustained cultural and commercial exchange. Featuring Ottoman ceremonies and monuments, this album attests to the early “Turkish fashion” in Dresden. The volume was created by the court painter Zacharias Wehme on the basis of a now-lost album that David Ungnad, the imperial ambassador in Constantinople, had sent to Dresden just a few years prior. This drawing focuses on the Hagia Sophia—built as a Christian place of worship and converted to a mosque after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453. The left side of the composition includes a flap that, when opened, reveals the tomb of the recently deceased Sultan Selim II.

Zacharias Wehme

German, 1558–1606

Hagia Sophia with the Türbe (Tomb) of Sultan Selim II (1524–1574, r. 1566–74) and an Ottoman Procession, 1581–82

Pen and gray ink, brush and white, silver, and gold watercolor and opaque watercolor, mounted on blue paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. CA 170/8

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Zacharias Wehme

Native to New Guinea and surrounding islands, birds of paradise—or rather, their dried and dissected skins—first reached mainland Europe in 1522. Collectors admired the birds’ iridescent feathers and were puzzled by what they perceived to be an unusual anatomy. When birds of paradise were dissected and their skins prepared for export to Europe, their feet were usually removed, which led to the false belief that the species was in constant flight. This drawing marvels at the bird’s brilliant plumage, executed in varied shades of brown, black, and white watercolor. It likely depicts the first bird of paradise recorded to have reached the Dresden court at the end of the sixteenth century.

Zacharias Wehme

German, 1558–1606

Dead Bird of Paradise, ca. 1580–90

Watercolor and opaque watercolor

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1961-86

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Master of Frankfurt

On the eve of his crucifixion, after the Last Supper, Christ visited the Garden of Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives with the apostles Peter, John, and James. Withdrawing in prayer, Christ asked his companions to watch over him, but while he prayed, the apostles were overcome by sleep. The Master of Frankfurt’s fully realized drawing depicts Christ among the sleeping disciples, with the later saints Jerome and Francis of Assisi, both animated in their devotion, added as flanking figures. The highly finished and elaborately worked sheet carefully combines gradations of wash and white heightening against a gray preparation, lending the scene a subtle nocturnal atmosphere and its figures a volumetric presence.

Master of Frankfurt

Netherlandish, ca. 1460–ca. 1525

Christ on the Mount of Olives with Saints Jerome and Francis, ca. 1495–1510

Brush and gray-brown and black ink, and gray wash, heightened with white, on gray prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 792

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

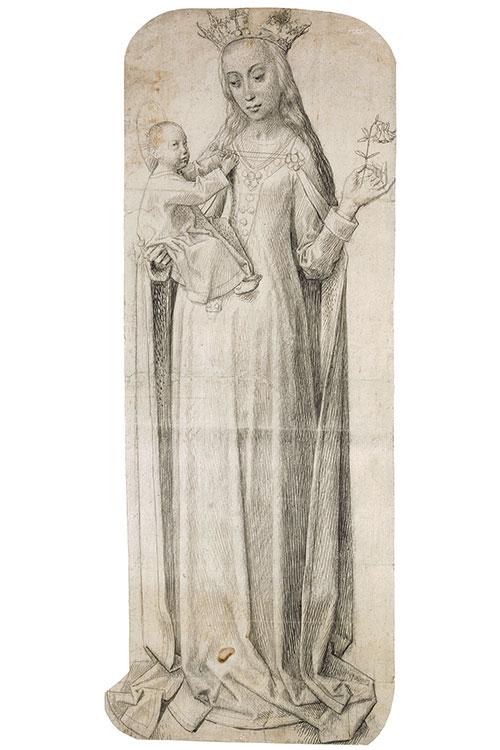

Follower of Hugo van der Goes

The solemn Virgin Mary, crowned as the Queen of Heaven, holds both the Christ Child and a columbine, a flower with dove-shaped petals that alludes to the Holy Spirit in the Christian tradition. The drawing’s unusually large scale and the columnar folds covering the Virgin’s elongated legs emphasize the contained verticality of this quiet scene. As a result, the standing Virgin, depicted frontally, gives the impression of a sculptural work enclosed in a niche. The composition relates to paintings by the Early Netherlandish master Hugo van der Goes and his followers. Moreover, the technique—the work is drawn with the tip of a paintbrush, mixing regularized parallel hatching with short comma-like strokes—is one used by the master and his circle.

Follower of Hugo van der Goes

Netherlandish, ca. 1440–1482

Standing Madonna and Child with a Columbine, ca. 1480–90

Brush and gray and black ink over black chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 811

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Erhard Altdorfer

Landscape first emerged as an independent pictorial subject in prints, drawings, and paintings of the Danube School—a group of artists active in Germany and Austria in the first half of the sixteenth century. Trained in the workshop of his older brother, Albrecht, a central figure among the Danube artists, Erhard Altdorfer was a very early adopter of the genre. This drawing depicts an imaginary landscape with an enormous, highly stylized tree, craggy mountains, and a river, which winds toward a small town in the distance. Altdorfer structured the composition using tightly spaced parallel- and cross-hatching, as well as looser, spiraling lines, which describe the clouds and shrubbery.

Erhard Altdorfer

German, 1480–after 1561

Mountainous Landscape with a Bridge, ca. 1530

Pen and black ink on red prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1900-74

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Observation and Fantasy, 1600–1750

Drawing in this period is characterized by the productive tension between the close observation of natural phenomena and an exuberant, unconstrained play of imagination. On the one hand, artists continued to deeply engage with subjects from the Christian tradition and ancient mythology, constructing complex narrative compositions and often imbuing them with an intense emotional charge. On the other, they looked closely at the world around them, producing acutely observed and confidently rendered studies. Portraiture—and especially self-portraiture—gained renewed importance, as seen here in works by Carlo Maratti and Anton Raphael Mengs. Made thirty years apart, two drawings by Rembrandt represent the Kupferstich-Kabinett’s rich historic collection of works by the innovative Dutch artist, as well as his students and associates.

Jan Harmensz. Muller

Like many other artists active in central and northern Europe at the end of the sixteenth century, Muller had a liking for subjects both erotic and esoteric. This drawing focuses on a littleknown passage from Homer’s Odyssey, featuring the brief and tragic love affair between Demeter, the Greek goddess of agriculture—known as Ceres in Roman mythology—and the young hero Iasion. Here, the artist depicts the moment when the lovers are discovered by Jupiter. As the canopy hanging over the bed flies open, vivid rays of light, emanating from Jupiter, illuminate their entangled bodies. The figures’ oversize limbs and contorted poses, delineated using pen lines that swell and break with a nervous rhythm, are typical of Muller’s early draftsmanship.

Jan Harmensz. Muller

Netherlandish, 1571–1628

Ceres and Iasion Discovered by Jupiter, ca. 1589–90

Pen and black ink, brush and brown wash, heightened with white, partially incised, on reddish prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 888

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Rembrandt van Rijn

In this drawing, Zeus (known as Jupiter in Roman mythology), disguised as an eagle, abducts Ganymede, a young Greek hero hailing from the city of Troy. Although Ganymede was admired for his unmatched beauty and often depicted in an erotically charged manner, Rembrandt characterizes him as a frightened, unruly toddler who squirms and screams as Zeus carries him away. The artist’s exuberant marks range from bold, zigzagging lines, which delineate the eagle’s body, to the loose swirls on the right side of the composition, which do not seem to serve a specific descriptive function. The drawing was used as a preparatory study for Rembrandt’s painting The Abduction of Ganymede, which is also part of the Dresden collection.

Rembrandt van Rijn

Dutch, 1606–1669

The Abduction of Ganymede, ca. 1635

Pen and brush and brown ink

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1357

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Austeja Mackelaite, Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator of Drawings and Prints

In the mid-1630s, the young Rembrandt enjoyed a high point in his career. He had recently moved from his native Leiden to Amsterdam, where he joined the local painters’ guild and began to practice as an independent master. Drawings from this period exhibit dynamism, bravura, and freshness of observation. As we look closely, we are able to witness Rembrandt’s imagination at work by tracing the quick movements of his hand.

In this sheet, the artist took up a story from Greek mythology. As Homer described in his Illiad, written in the eighth century BC, Zeus—the chief deity in the Greek pantheon—fell in love with the young Trojan youth, named Ganymede. Here, Rembrandt imagines the culmination of the story’s dramatic arc. He shows Zeus, who has turned himself into an eagle, abducting Ganymede from Mount Ida near Troy and getting ready to carry him to Mount Olympus, the home of the gods.

While artists have traditionally represented Ganymede as an adolescent, Rembrandt depicts him as a fussy toddler being separated from his parents—the two figures with their arms up, roughly sketched at lower left corner. His pen and brush move quickly across the sheet, filling the space with a variety of marks—from fine and deliberate strokes, which describe child’s grimace of desperation, to extremely loose, non-descriptive, squiggly lines, which might evoke gusts or currents of air.

Rembrandt van Rijn

Made three decades after The Abduction of Ganymede, on view nearby, Diana and Actaeon exemplifies the reduced, angular manner of drawing that Rembrandt developed in his late works. At left, Diana, the Roman goddess of the hunt, is bathing in the company of her nymphs. The group is observed by the young mortal Actaeon, who stands on an elevated bank at right, behind a large tree trunk. As described by the Roman poet Ovid, Diana punishes Actaeon’s voyeurism by transforming him into a stag. In this sheet, Rembrandt simultaneously portrays the moment when the goddess realizes that she has been observed and the subsequent punishment, showing Actaeon as part human and part animal, with his face transformed into a muzzle and antlers sprouting from his head.

Rembrandt van Rijn

Dutch, 1606–1669

Diana and Actaeon, 1663–65

Pen and brush and brown ink, with traces of white opaque watercolor

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1384

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Jan Lievens

This sheet belongs to a group of large-scale, highly finished drawings that Lievens created in the early years of his career. It focuses on the suspenseful banquet that Esther, an Old Testament heroine, prepared for her husband, the Persian king Ahasuerus, and his vizier, Haman. With her gaze fixed on Ahasuerus, Esther gestures emphatically toward Haman, who had been secretly plotting to annihilate the Jewish people. As his vicious plan is being uncovered, Haman crouches in his chair, his face submerged in the shadows. The drama of the event is enhanced by Lievens’s bold use of chiaroscuro effects and his decision to position the figures in the middle ground, with a curtain framing the composition at left, which effectively transforms the scene into a stage.

Jan Lievens

Dutch, 1607–1674

The Feast of Esther, ca. 1628

Brush and black and gray ink, gray and brown wash, heightened with white, over black chalk, with traces of red chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1980-463

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

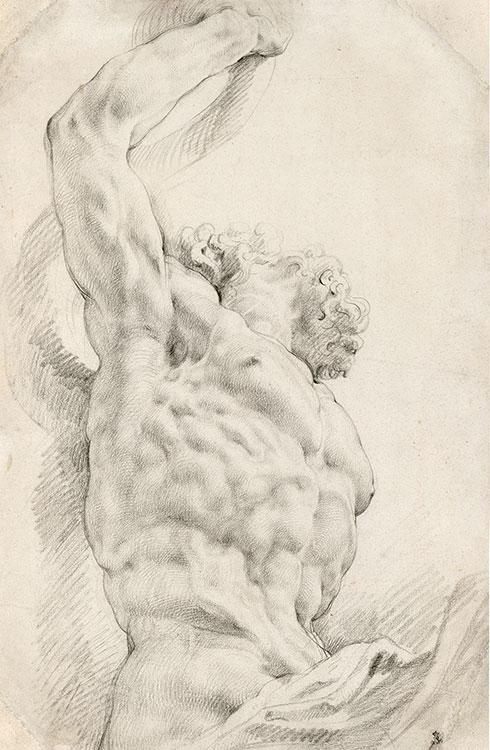

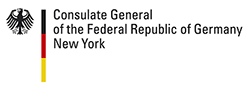

Peter Paul Rubens

During his two visits to Rome, Rubens studied the Laocoön (shown below) more intently than any other ancient statue. The chilling depiction of the anguished Trojan priest, struggling to release himself from the tight coils of the snakes that threaten to suffocate him and his two children, provided the artist with an opportunity to observe a male body engaged in an intense physical struggle. Rubens created a dense, pulsating network of lines, methodically capturing the tense muscles and protruding veins of Laocoön’s torso and right arm in black chalk. The sculpture is observed from below and sideways, exemplifying the artist’s interest in finding unusual and dynamic viewpoints when drawing ancient sculpture.

Peter Paul Rubens

Flemish, 1577–1640

Torso of Laocoön, ca. 1601–2

Black chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1874-22A

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Peter Candid

Born in the Netherlands, Candid spent most of his early life in Florence, where he was active as a painter and tapestry designer. In 1586, he moved to Munich, joining the cohort of international artists working for Wilhelm V, Duke of Bavaria. This drawing served as a preparatory study for a print commemorating the foremost architectural project in the city at this time—the construction and decoration of Saint Michael’s Church. It reproduces one of the building’s principal façade elements, a large bronze sculpture representing the archangel Michael defeating the devil. Composed of layers of delicate gray wash and dense areas of hatching, the drawing successfully conveys both the sculpture’s intricate surface detail and its overall monumental effect.

Peter Candid

Netherlandish, 1548–1628

The Archangel Michael Defeating the Devil, ca. 1597

Black chalk, pen and brown ink, brush and gray wash, heightened with white, traces of red chalk, incised, on light-brown prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 885

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Tanzio da Varallo

This sensitive drawing, which depicts an angel leading the soul of a deceased man to heaven, was made by Tanzio in preparation for his fresco decorations in the Chapel of the Guardian Angel in the Basilica of San Gaudenzio, Novara, completed in 1629. The drawing corresponds closely with two figures painted in the chapel, who glide aloft on clouds at the base of the vault. The angel guides the deceased with his right hand and gestures with his left, directing his charge to look up toward the vault’s apex, where Christ appears. Tanzio’s finished study focuses on this moment of divine revelation, delicately rendering the interplay of light and shadow across the figures.

Tanzio da Varallo

Italian, ca. 1582–1632/33

An Angel Guides a Deceased Believer to the Kingdom of Heaven, ca. 1628–29

Red chalk on reddish prepared paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1937-840

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Hendrick Goltzius

Characterized by a strong sense of immediacy, this drawing was likely based on a life study. Goltzius outlined the contours of the figure’s headdress and face using swift, sharp strokes of red chalk, and skillfully described the soft surface of the skin by rubbing powdery red pigment with a finger or stump. Despite the drawing’s compelling naturalism, the identity of the subject remains unclear. While scholars have traditionally referred to the figure as an older woman, the thick neck with the Adam’s apple protruding right below the chin, the unruly short hair playfully sticking out from underneath the headdress, and the overall lack of idealization suggest that the subject may be a male figure in a chaperon, a type of headwear popular in the Middle Ages.

Hendrick Goltzius

Netherlandish, 1558–1617

Head Study, ca. 1605–10

Red chalk, incised

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 897.

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

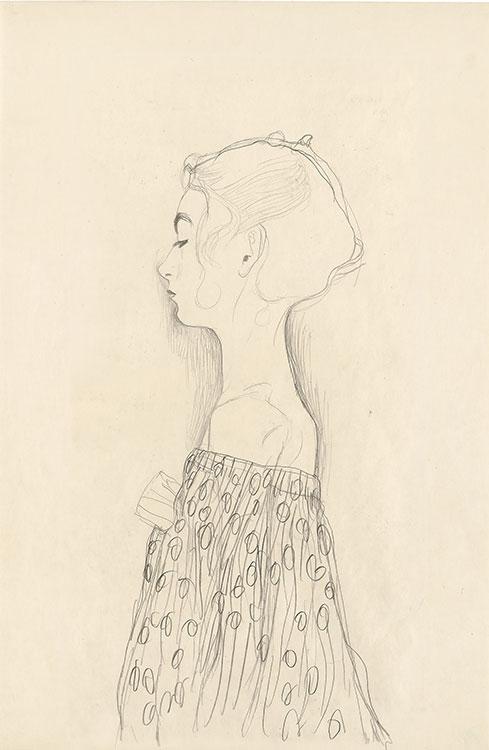

Sofonisba Anguissola

Anguissola was born to a noble northern Italian family and, together with her six siblings, received a comprehensive humanistic education and training in the art of painting. Perhaps because her gender precluded her from studying anatomy or working with nude models, she focused on portraiture, often turning to sitters in her familial and social circles. This study, which might be a self-portrait, is an example of the artist’s direct yet sensitive approach to the portrait genre and her assured drawing technique. Although Anguissola’s drawing skill was praised by her contemporaries, extremely few sheets by the artist survive today.

Sofonisba Anguissola

Italian, ca. 1535–1625

Portrait of a Lady with a Feathered Hat (Possibly a Self-Portrait), ca. 1575–1600

Black chalk on gray-blue paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1937-785

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator and Department Head

Sofonisba Anguissola was the most famous woman artist of the Italian Renaissance. She was born in Cremona, Italy, and was trained as a painter by Bernardino Campi, the leading artist in that city, but she also received a humanist education. Her fame as a painter quickly spread, not only in Italy but across Europe, and in 1559 she was invited to Spain to serve as a lady-in-waiting to the queen. While in Spain, she painted many portraits of the royal family and other members of court. She spent more than a decade in Madrid before marrying a Sicilian nobleman and returning to Italy.

Relatively few drawings by Sofonisba survive, but the Dresden sheet agrees in style with the few secure examples, and the early inscription at the bottom of the sheet also attributes it to her. It could in fact be an image of the artist herself. Sofonisba painted a series of self-portraits, more than any woman before her time, and the shape of the face, the almond-shaped eyes, and the slightly pointed ears of the woman in this drawing resemble those in the paintings, as does her sidewards but direct gaze. The open-necked dress and feathered hat would have been unacceptable at the Spanish court, however, so this drawing was probably made either just before her departure from Italy, or else just after her return.

Antoine Watteau

Study with Four Pilgrims and a Cupid relates to Watteau’s painting The Embarkation for Cythera. He first depicted the subject around 1709–12 and returned to it a few years later, producing two variations. In these convivial works, groups of elegantly dressed young people mingle in bucolic settings as they prepare to embark for the Greek island that was, according to classical legend, the birthplace of Aphrodite, the goddess of love. In 1717, the French Academy described Watteau’s Embarkation for Cythera as a fête galante, giving a name to the genre that would become the artist’s signature development. In this drawing, Watteau adeptly varied the pressure of the red chalk to define the fashionable characters.

Antoine Watteau

French, 1684–1721

Study with Four Pilgrims and a Cupid, ca. 1709–12(?)

Red chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 734

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

The term fete galante, used to describe a group of men and women in elegant dress at leisure in the landscape, came into use around 1700 and in fact such scenes of outdoor romance already were gaining currency in theatrical productions of the 1690s. Nevertheless, Watteau’s evocation of Cythera in the canvas at the Louvre remains the most poetic and memorable example of the genre.

Watteau spent the majority of his career outside the official French academy. He drew incessantly, making studies and carrying them in a portfolio, turning to this repository when he needed figures for paintings. The separate studies scattered across this page, with their mix of orientation and scale, reveal Watteau’s process of compiling individual motifs rather than devising a composition first and then methodically making studies of each figure in it. The male figure wearing the theatrical costume of a stylish follower of Venus is drawn three times on the sheet in different poses, and appears in a few versions of the painted composition while the female devotee at center—who seems as if she’s the main study on the sheet—was not used in a painting. As your eye roves across the page, the individual studies reveal several moments of creation that eventually contributed to one of the most celebrated paintings in Western art.

Anton Raphael Mengs

Considered one of the pioneers and most important representatives of Neoclassicism, Anton Raphael Mengs began his training as a child under his father, the Saxon court painter Ismael Mengs. Anton Raphael graduated from this early, intensive tutelage around 1740, when he was twelve years old—the same year that Ismael and his children began a fouryear stay in Italy to continue their artistic education. This remarkable self-portrait, the earliest to survive by Anton Raphael, was drawn in that year, before the family’s move. A testament to the artist’s precocious talent, the drawing sensitively blends the black and red chalk to create a lifelike record of the young Mengs’s features as studied in a mirror.

Anton Raphael Mengs

German, 1728–1779

Self-Portrait at Twelve Years Old, 1740

Black and red chalk

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 2464

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

What did it mean in 1740 to be a twelve year old draftsman capable of wielding colored chalks to capture your own likeness? This self-portrait is an unusually accomplished piece of juvenilia, and rarely do we have datable works for this early stage of an artist’s career. The German tradition, however, is curiously strong in such works: among the most memorable being a striking self-portrait executed in 1484 by a 13 year old Albrecht Durer. At the time Mengs executed this sheet, he was under his father’s tutelage and transitioning from making copies to drawing from life. We see one of his first forays into drawing aided with a mirror, as he uses himself as the model. An old slip of paper once attached to the back of the drawing notes that Mengs gave the sheet to a classmate before the artist and his family departed for Italy. This practice of giving and exchanging drawings would flourish among young German artists in the nineteenth century.

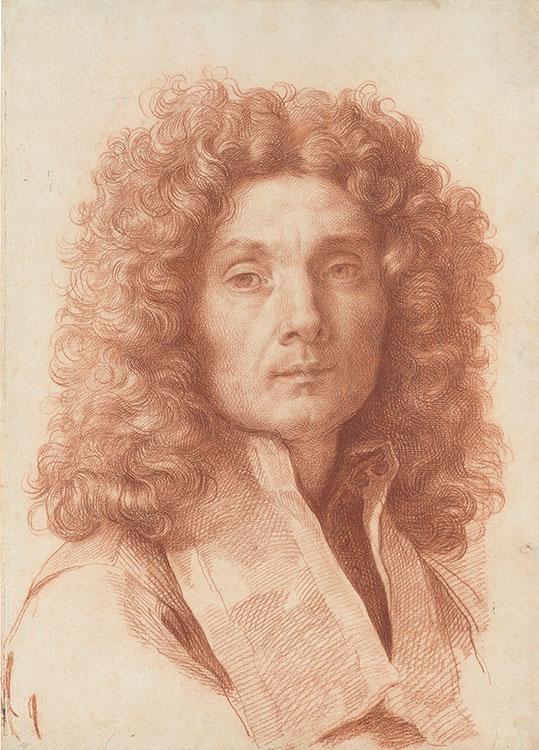

Carlo Maratti

In this large and commanding self-portrait, Maratti, one of the leading protagonists of the Roman Baroque, represents himself at about the age of sixty, when he was at the height of his artistic influence. In a virtuosic display, the artist elaborated his features and the fall of light with a meticulous network of cross-hatching using a sharp piece of red chalk. The drawing was not made in preparation for a painting but is instead an autonomous work of art, serving as both a record of Maratti’s likeness and a potent demonstration of his artistic abilities.

Carlo Maratti

Italian, 1625–1713

Self-Portrait, ca. 1680–85

Red chalk (in two shades)

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 243

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator and Department Head

Carlo Maratti was from the late seventeenth century until his death in 1713 one of the leading artists in Rome, the heir to a classicizing tradition that began with Raphael and extended through the work of Annibale Carracci. He received the most traditional of Italian artistic educations, being made to master draftsmanship before turning to painting, and to engage in extensive life drawing as well as copying classical sculpture and paintings of the great masters. Hundreds of surviving drawings by him demonstrate that draftsmanship remained essential to his art throughout his career… and his remarkable abilities as a draftsman can be seen in this sheet. It is one of series of self-portrait drawings that Maratti made in the early 1680s, when he was at the height of his powers and was the head of the largest, most important painting workshop in Rome.

Maratti’s painted portraits are often somewhat idealized, and they often include elaborate draperies and props that indicate the sitter’s occupation or status, but his portrait drawings – especially the self-portraits – instead reflect his ability to observe and capture appearances and personalities. Especially in a large sheet like this, we marvel at Maratti’s vitality and presence, emphasized by his gaze directly out at the viewer, even as we also appreciate his remarkable facility to evoke the textures of flesh, hair, and fabric in his preferred medium of red chalk.

Francisco de Goya

A group of monks, identified by their habits, pore over an open book; uneven light flickers across the scene, deftly rendered with brush and wash. The relationship and significance of the older man and younger woman standing together behind the main group, seemingly uninterested in seeing the volume, are ambiguous. The caricature-like faces and coarse delight of the three monks in the foreground imply that their book is not devotional and announce the drawing’s satirical nature. This sheet comes from one of several private albums that Goya compiled throughout his career. As in many of his published prints, the imagery in these drawings is replete with social criticism directed at the clergy, among others.

Francisco de Goya

Spanish, 1746–1828

Monks Reading, ca. 1812–20

Brush and brown wash

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1910-56

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

John Marciari, Charles W. Engelhard Curator and Department Head

Francisco de Goya is best known for his paintings and his remarkable etchings, but he made some of his most personal and mysterious works in the drawing sketchbooks and albums that remained in his possession until his death. This was especially true late in his life, when a mysterious illness had left him deaf, and the Napoleonic wars had ended his close association with the Spanish court. The aging artist turned inward, producing scores of drawings like this work, and others that include satirical and cynical looks at contemporary life, alongside scenes of war, savagery, and witchcraft.

This sheet comes from an album that originally contained around 90 densely worked drawings made on writing paper with a brush and a corrosive brown ink, materials presumably adopted because of of good drawing paper and ink were not readily available during the war. In contrast to many of Goya’s drawings, those in this album generally do not have captions, and so they remain open to interpretation. Here, we see a group of seated monks in the foreground, but their coarse expressions suggest that their reading is something other than sacred literature. Behind them stand a woman, who seems to be hiding herself from the leering monks, and an older, apparently toothless monk looking upward, perhaps embarrassed by his companions or else because of his great age no longer interested in their activities.

Portrait of Muhammad ‘Ādil Shāh

This album, containing dozens of portraits by several artists of rulers and noblemen from the Mughal Empire and the Deccan, was in the possession of the Dresden court by the end of the seventeenth century. Following a traditional representational style, these two portraits show Muhammad ‘Ādil Shāh, Sultan of Bijapur, at right, and Ikhlās Khān, his military commander and influential minister, at left. Often copied from earlier depictions, the subjects of the album’s portraits are identified by specific physical characteristics and attributes such as attire and weapons, though the artists expressed their individuality by introducing subtle variations. In the right-hand portrait, the unknown artist’s creativity and skill are especially evident in the depiction of the transparent muslin skirt.

Unknown artist

India (Deccan sultanates, Golconda)

Muhammad ‘Ādil Shāh, Sultan of Bijapur (r. 1627–56) (right) and Ikhlās Khān (d. 1656) (left), 1668–89

Opaque watercolor and gold; frame: gold, framing lines in black ink, on a ground flecked with green watercolor

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NOS. CA 112/7 AND CA 112/8

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Austeja Mackelaite, Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator of Drawings and Prints

The Kupferstich-Kabinett holds a small but important collection of Indian miniature paintings from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Some of the works—including this seventeenth-century volume—entered the collection shortly after they were made. An inscription inside the book proves that it was in German possession by 1689 at the latest—an unusually early date. It probably reached Germany via Amsterdam, through the Dutch East India Company, which dominated European trade with Asia at this time.

The book includes depictions of rulers associated with four Indian dynasties. The subjects are identified in inscriptions at the center of each sheet; they are also recognizable through specific physical characteristics, attire, and weapons, as well as other attributes. In the image at right, Mohammed Adil Shah, Sultan of Bijapur [Bee-zha-poor], is placed against a plain background, boldly rendered in blue opaque watercolor. He is holding a flower, as an indication of his cultivated refinement. The image at left depicts Ikhlās Khān, a formerly enslaved man of Ethiopian descent, who served as a military commander and powerful advisor to the sultan. Khan is wearing a pink tunic and a jacket decorated with flowers, and holds a sword and a shield in his hands. The two men worked closely together and were often depicted side by side, as here.

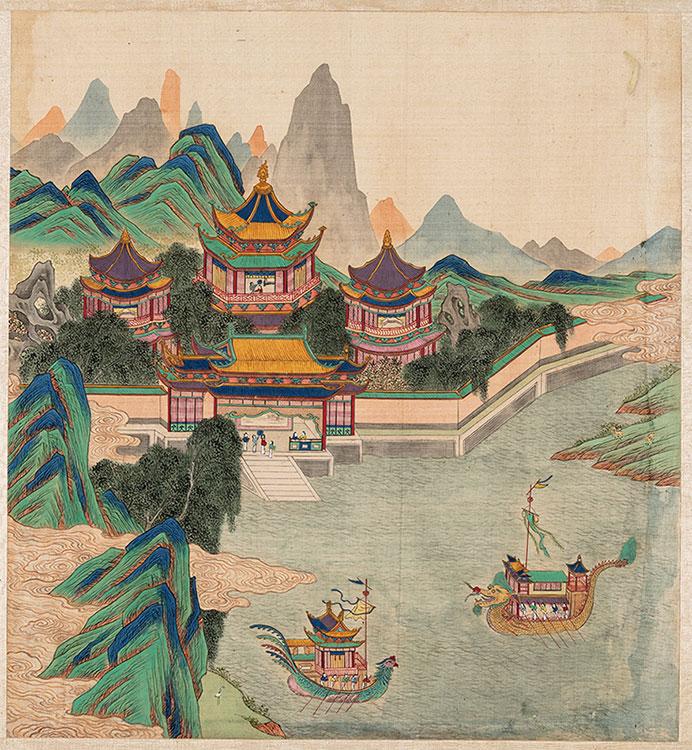

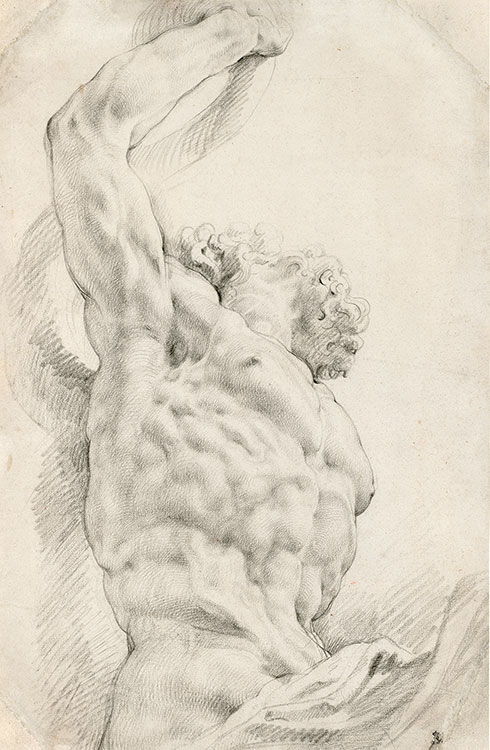

Palace Garden with Ceremonial Barques

This boldly colored depiction of two groups of women rowing ceremonial boats before a palace garden backed by mountains belongs to a genre known as xingle xt (行乐图, pictures of life at leisure). The idyllic scene was executed using the exacting Gongbi technique (工笔, Careful Brush Technique), combining meticulous brushwork, bold colors, and jiehua, the precise rendering of architecture with a traditional ruler called a jiechi (界尺). This late Ming dynasty watercolor is one of nine related landscapes in Dresden that descend from the collection of Nicolaas Witsen (1641–1717), a mayor of Amsterdam and collector of Asian art. The Kupferstich-Kabinett acquired several Chinese and Indian works from the sale of Witsen’s estate in 1728.

Unknown artist

China

Palace Garden with Ceremonial Barques, first half of the seventeenth century, late Ming dynasty

Brush and watercolor and opaque watercolor on silk, mounted on cardboard

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. CA 132/5

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Andreas Diesend

Bernardo Bellotto

In the first half of the eighteenth century, the architectural and cultural landscape of Dresden underwent a radical transformation. Focused on making the city into a major European capital, the Saxon rulers commissioned ambitious architectural projects and assembled a remarkable number of foreign artists at the court. Bellotto arrived in Dresden in 1747, bringing with him the Venetian tradition of vedute, or highly detailed topographical views. In this work, the viewer gazes from the right bank of the Elbe River toward the Augustus Bridge and the Old Town. The Dresden Castle, where the Kupferstich-Kabinett is located today, can be seen on the far right of the image, behind the newly built Dresden Cathedral. The only print included in the exhibition, this view conveys the splendor of Dresden during the decades shortly after the official establishment of the Kupferstich-Kabinett.

Bernardo Bellotto

Italian, 1722–1780

Dresden from the Right Bank of the Elbe, Below the Augustus Bridge, 1748

Etching; state I (of IV)

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. A 85857

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Romantic Artists in Dialogue with Nature

At the close of the eighteenth century, as the political and cultural geography of Europe was shifting, Dresden became a major center for Romantic literature, philosophy, and art. A new enthusiasm for nature among artists led to the reevaluation and flourishing of the landscape genre. Caspar David Friedrich, who moved to the city in 1798, imbued his close studies of nature with an emotional and spiritual dimension. While Friedrich never traveled south of the Alps, works by the next generation of artists—Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Theodor Rehbenitz, Franz Theobald Horny, and Ernst Ferdinand Oehme—attest to the importance of a prolonged stay in Italy in the training and development of many northerners. Draftsmen made extensive use of watercolor and sepia washes, resulting in highly finished, painterly drawings that were appreciated as works of art in their own right. Actively collected by the Kupferstich-Kabinett during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, drawings from the Romantic period are one of the institution’s great strengths.

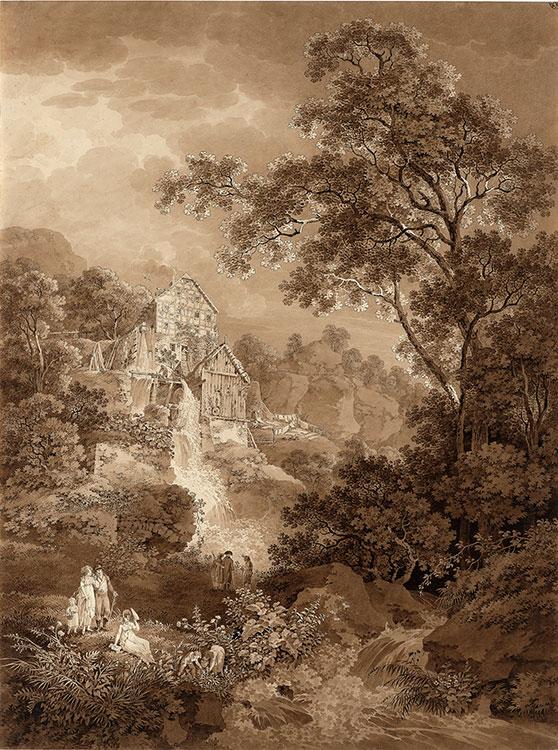

Adrian Zingg

After training as an engraver in his native Switzerland and working in Paris, Zingg moved in 1766 to Dresden, where he joined the faculty of the newly established Academy of Fine Arts. Combining topographical accuracy with a penchant for the picturesque, and taking inspiration from the local environment, his drawings paved the way for the Romantic landscape tradition that developed in Dresden in the nineteenth century. This large sheet depicts the Keppmühle—a charming mill that was one of the most popular excursion sites for Dresdeners at the time. The landscape is rendered in Zingg’s characteristically ornamental style, with extensive application of sepia washes and skilled use of the white of the paper, creating an enchanting impression of illumination.

Adrian Zingg

Swiss, 1734–1816

The Keppmühle near Dresden Hosterwitz, ca. 1794

Pen and black-brown and gray ink and brown wash

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1977-155

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Andreas Diesend

Caspar David Friedrich

This large sepia study attentively renders a constellation of boulders, stones, and pebbles scattered on a beach. Infused with quiet melancholy and devoid of signs of human presence, the work explores atmospheric conditions and the effects of light. It is difficult to know whether the luminous celestial body at the center of the composition is supposed to represent the moon or the sun. In either case, Friedrich’s predominant concern is depicting the moment of transition between night and day, darkness and light.

Caspar David Friedrich

German, 1774–1840

Stony Beach at Moonrise (Stony Beach with Setting Sun), ca. 1835–37

Brush and brown ink over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 2605

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Andreas Diesend

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints

At the time he drew this sheet, Friedrich was entering his 60s and recovering from a lingering professional disappointment. A decade prior, he failed to ascend to the position of teaching landscape painting at the Dresden Academy and experienced a year long illness, events that left him pensive and increasingly isolated. After he suffered a stroke in 1835, he could no longer paint and resumed making wash drawings. Given Friedrich’s deep spirituality, it isn’t surprising that his late drawings reflect a more somber state of mind as he dwelled on thoughts of life’s end.

The reverence that he had for nature emerges in the way he wields his materials to evoke this tranquil coastal scene, devoid of figures. Friedrich returned to a sketch he had made of the beach at Rugen in 1801 and transferred part of it to this sheet. The evocation of this specific site at moonlight engaged Friedrich’s memory and lived experience, and this underlying sense of time’s passage lends an elegiac tone to this tranquil view.

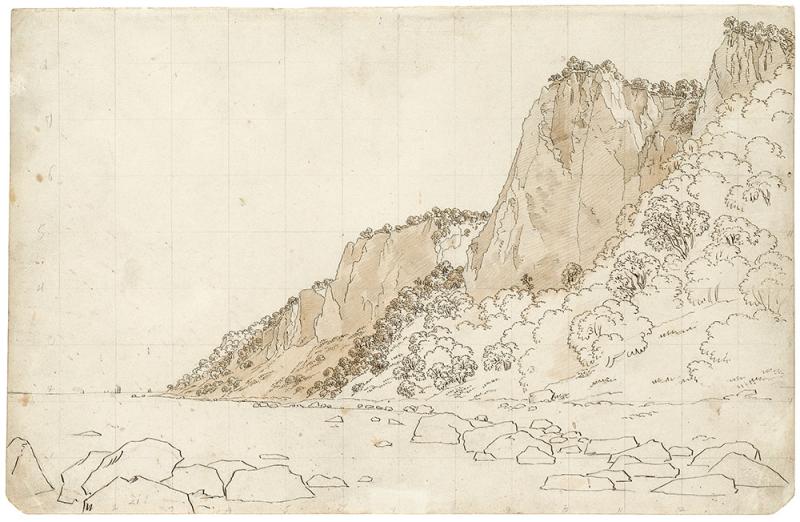

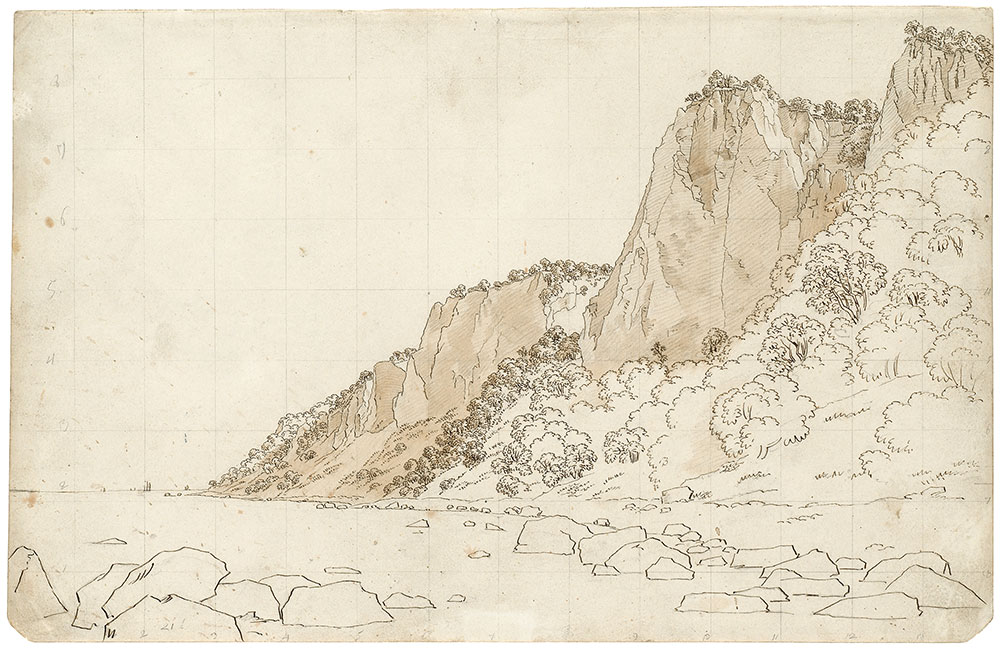

Caspar David Friedrich

Rügen—a large island in the Baltic Sea, off the coast of Germany—was an important destination for Friedrich. The drawings he made during his numerous trips to the area focus on dramatic chalk cliffs and rugged, stony beaches, capturing the island’s austere, windswept character. In this sheet, the artist reduced the Rügen landscape to its most essential features, relying on clear, precise contours and sparingly applied washes. Friedrich frequently used the landscape motifs he developed in such works as the basis for highly finished sepia drawings, such as Stony Beach at Moonrise (Stony Beach with Setting Sun), on view nearby. In order to transfer his compositions to other formats, Friedrich often squared his sketches, as is the case here.

Caspar David Friedrich

German, 1774–1840

Stubbenkammer on Rügen, 1801

Pen and black ink and brown wash over graphite pencil; squared

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1968-357

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

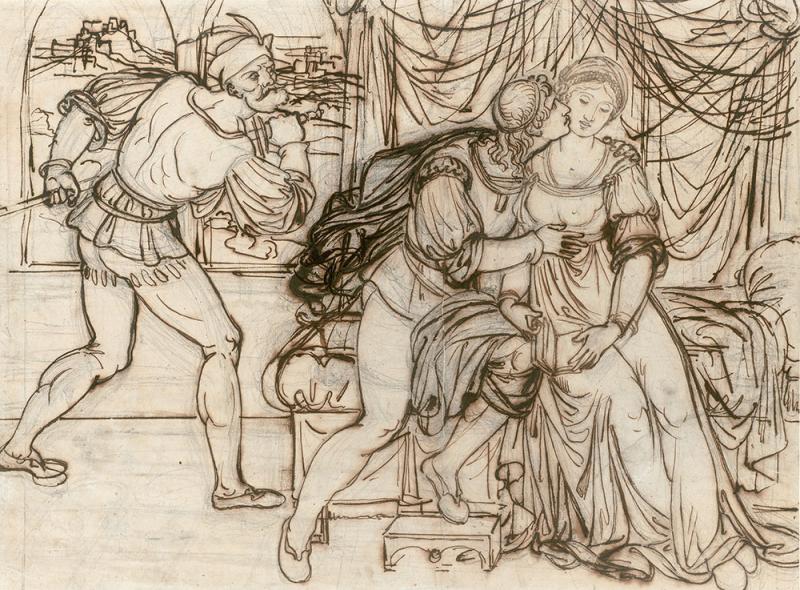

Joseph Anton Koch

Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, one of the most important works of medieval literature, was first translated into German at the turn of the nineteenth century. It immediately became a rich source of inspiration for Romantic artists; Koch alone produced over two hundred drawings and a large number of prints illustrating the text. In this sheet, the artist focused on the tale of Francesca and Paolo, who fall in love upon reading the story of the legendary knight Lancelot. While the couple is gently embracing in Francesca’s bedchamber at right, the left side of the composition is dedicated to the enraged, seething figure of Gianciotto— Francesca’s husband and Paolo’s brother—who has just discovered the illicit affair.

Joseph Anton Koch

Austrian, 1768–1839

Paolo and Francesca, 1802–5

Pen and brown ink over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1908-289

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Ian Hicks, Moore Curatorial Fellow

In addition to being one of the most important landscape painters of the early nineteenth century, Joseph Anton Koch was a writer and prolific draughtsman. After initial training in Stuttgart during his late teens and early twenties, the artist travelled to Switzerland to sketch the Alpine landscape. In early 1795, when he was twenty-six, the artist relocated to Italy. There, in addition to his heroic landscape paintings, Koch increasingly made figurative drawings, taking inspiration from classical, Medieval, and eighteenth-century literature.

In this drawing, we see the artist’s interest in literary narratives, namely his fascination with Dante’s Divine Comedy. The famous narrative poem was first translated into German at the turn of the nineteenth century and would become hugely influential for Romantic artists, including Koch, who produced over two hundred drawings related to the text. The artist here illustrates a scene from the ill-fated story of Francesca and Paolo, who fell in love with each other upon reading the story of the legendary knight Lancelot. The artist shows the moment when the lovers’ longstanding affair is discovered by Gianciotto – Francesca’s husband and Paolo’s older brother – who reaches to draw his sword before slaying the couple. The draughtsman’s pen brings a linear clarity to his more exploratory and energetic graphite sketch below. Though the figures are characterized by this precise approach with the pen, the agitated mass of Paolo’s cape and the more boldly rendered bed canopy lend the scene a dynamic charge.

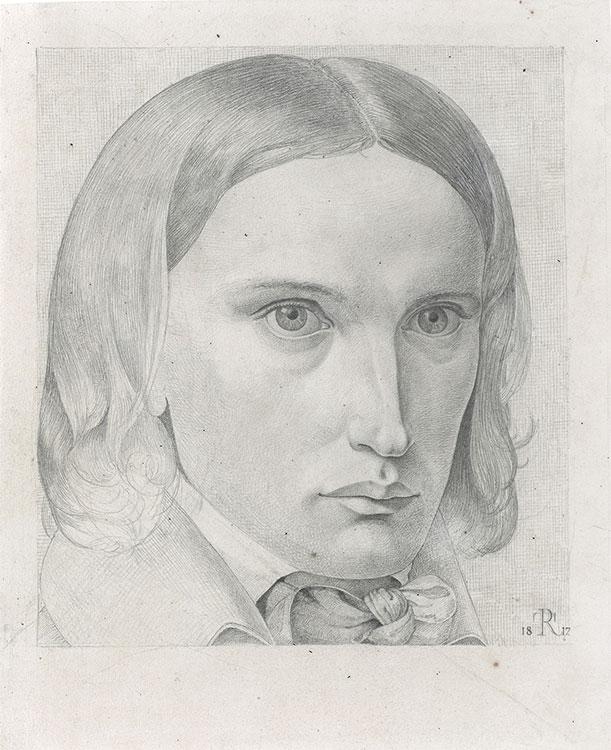

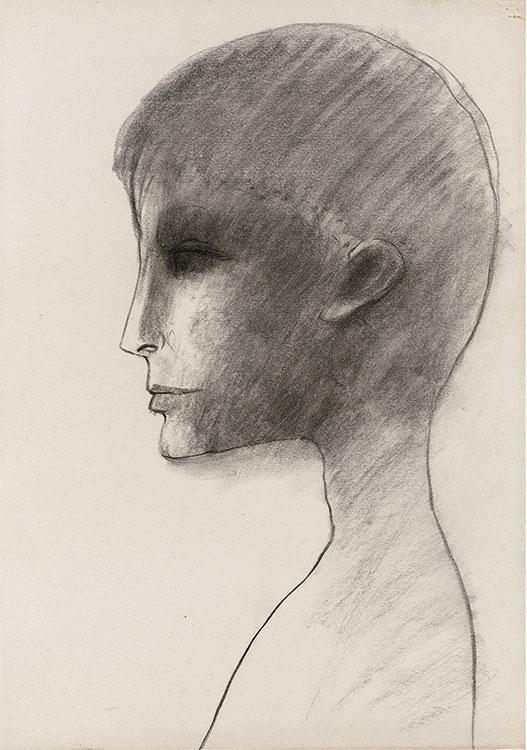

Theodor Rehbenitz

In his self-portrait of 1817, Rehbenitz describes his intense gaze with precise and controlled draftsmanship. Feathery networks of graphite lines carefully establish the shadows over his face; the highly finished study is exactingly rendered throughout, apart from the loose curls at left, which remain as more animated traces of the artist’s hand at work. Rehbenitz produced this signed and dated drawing a year after moving to Rome from Vienna, where he had been studying at the Academy of Fine Arts. In Rome, Rehbenitz joined the circle of German artists known as the Nazarenes, forming a Protestant faction of the group with Friedrich Olivier and Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, whose work is on view nearby.

Theodor Rehbenitz

German, 1791–1861

Self-Portrait, 1817

Graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 3327

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Franz Theobald Horny

In this drawing, Horny treats the delicate lily branch as a monumental form. Placed against a vivid green-blue background, the flower fills almost the entire space of the sheet. Through the combination of pen and ink, graphite, and translucent watercolor, the topography of individual petals is carefully described. The dark background, composed of richly layered washes, further enhances the lily’s palpable three-dimensionality. Although the drawing would seem to be an end in itself, it is connected to the artist’s work on the ceiling decoration of the Dante Hall at the Casino Massimo in Rome.

Franz Theobald Horny

German, 1798–1824

Lily, 1817

Pen and brown ink and watercolor over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1908-225

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

On a forested hill overlooking the Villa Piccolomini near Frascati, two young men in Renaissance-style dress break from their pastoral concert as two women approach. Though the characters that populate Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s scene are imaginary, the detailed landscape punctuated by brightly lit trees, skillfully described using the reserve of the sheet, derives from firsthand study. During the artist’s extensive travels in Italy from 1818 to 1827, he produced over one hundred landscape drawings, which were later bound in an album. Reflecting on these Italian works in 1867, Schnorr von Carolsfeld reminisced about the “ten exceedingly happy days” he spent in the countryside around the Villa Piccolomini, where he made this drawing.

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

German, 1794–1872

Park and Villa Piccolomini near Frascati, 1826

Pen and brown ink with brown and gray wash over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1908-819

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Ian Hicks, Moore Curatorial Fellow

Schnorr von Carolsfeld was inspired toward the genre of landscape through the example of the previous generation of German and Austrian artists, including Joseph Anton Koch, whose work is displayed elsewhere in the exhibition. Following their example, Schnorr von Caroslfeld journeyed to Italy, where he travelled extensively from his mid-twenties into his early thirties, producing over a hundred landscape drawings that were later bound into an album. As the artist’s inscription along the lower margin makes clear, this drawing details the wooded hills overlooking the Villa Piccolomini, near the town of Frascati. The sheet is dated 1826, toward the end of his Italian sojourn.

While the landscape and the play of light record the artist’s careful observation of nature, the figures are an imagined fantasy. They are clad in Renaissance-style dress, perhaps inspired by the sixteenth-century villa. The scene isn’t clearly tied to a known narrative, but rather shows a more generic pastoral encounter between the two couples, evoking an Arcadian ideal. In writing a series of letters some forty years later to describe the drawings in his landscape album, Schnorr von Carolsfeld would reveal the pleasure he took in creating the work. He fondly reminisced over, as he put it, the “ten exceedingly happy days” he spent in the countryside around the Villa.

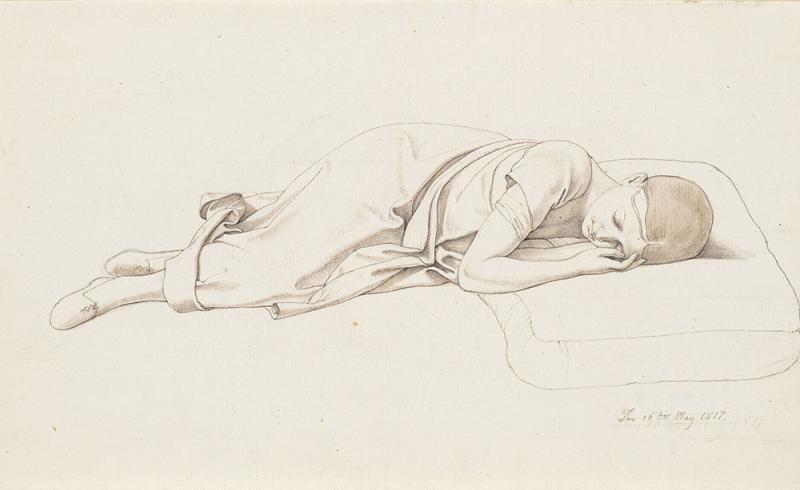

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

A key figure among German artists who lived and worked in Rome in the early nineteenth century, Schnorr von Carolsfeld received his initial training at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. This tender depiction of the ten-year-old Maria Heller dates to the end of his stay in that city. The artist captured the young girl as she slept, with her head and shoulder resting on a large pillow, and her feet protruding from underneath a light blanket. Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s use of crisp contours, sparing application of washes and hatching, and brilliant exploitation of the white of the paper itself result in an airy, ethereal image.

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

German, 1794–1872

Girl Lying Down (Maria Heller), 1817

Pen and brown ink with brown wash

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1938-30

Ludwig Richter

Made during Richter’s three-year stay in Italy, this drawing captures the vast, scenic landscape of the Roman countryside. The undulating hills extend rhythmically into the distance; they are composed of interchanging areas of gray and brownish washes, and sections of paper left blank. In the foreground, pious countrypeople are making their way to a small chapel located in a shaded valley at left. Unlike most of the landscape, the figures are rendered in outline only. While this gives the drawing an unfinished appearance, the artist likely left this area deliberately unworked to emphasize the impression of a radiant, sun-drenched Italian landscape.

Ludwig Richter

German, 1803–1884

Churchgoers near Rocca Santo Stefano, ca. 1824–25

Pen and brush and gray and brown ink and wash over graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1908-948

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Ernst Ferdinand Oehme

Oehme’s vibrant watercolor shows a view of the mountainous Rigi area of Switzerland, which he visited in August 1825 on his return home to Dresden after a three-year stay in Italy. The artist used clear contours to define the unfolding mountain ridges, which are stacked in colored tiers, thereby communicating an expansive recession away from the viewer toward distant snowcapped peaks. The sheet is part of a group of watercolors and paintings based on the sketches that Oehme made during the trip. The finished works focus on the austerity and vastness of the Alpine terrain, omitting all references to the tourism industry that flourished in the region at the time.

Ernst Ferdinand Oehme

German, 1797–1855

The Rigi, 1825

Pen and gray and brown ink and watercolor with white opaque watercolor

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1908-1257

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Andreas Diesend

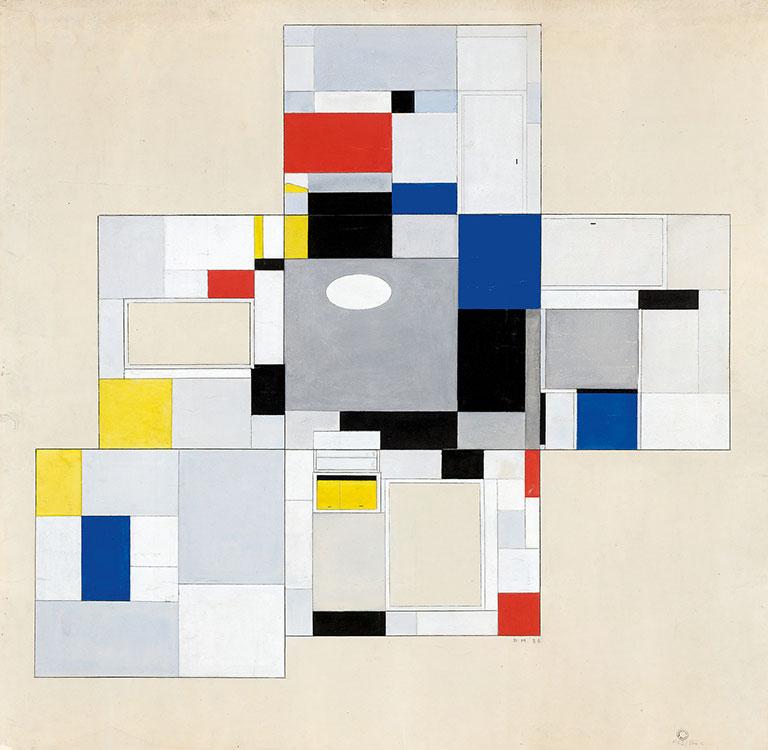

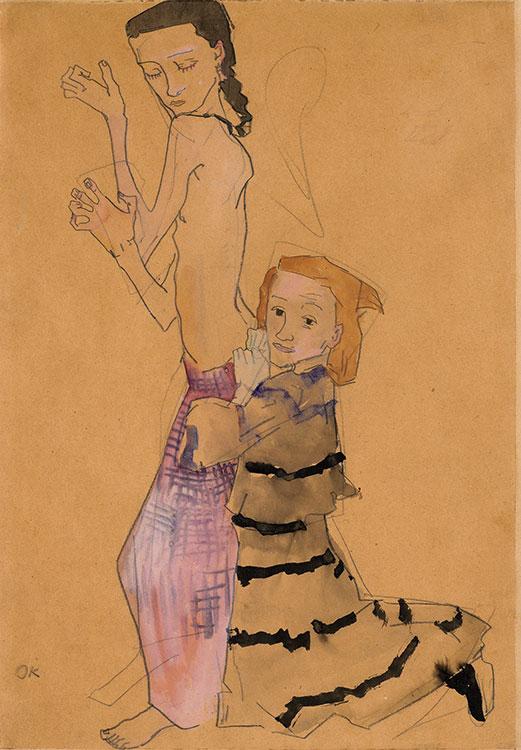

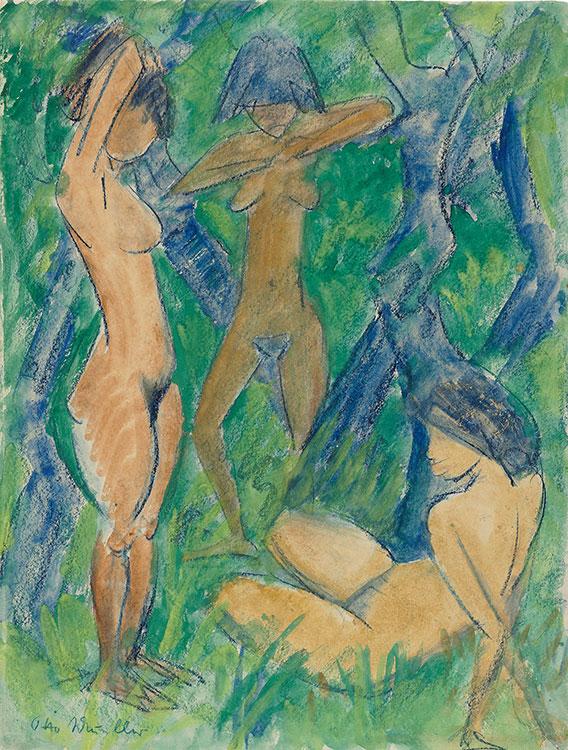

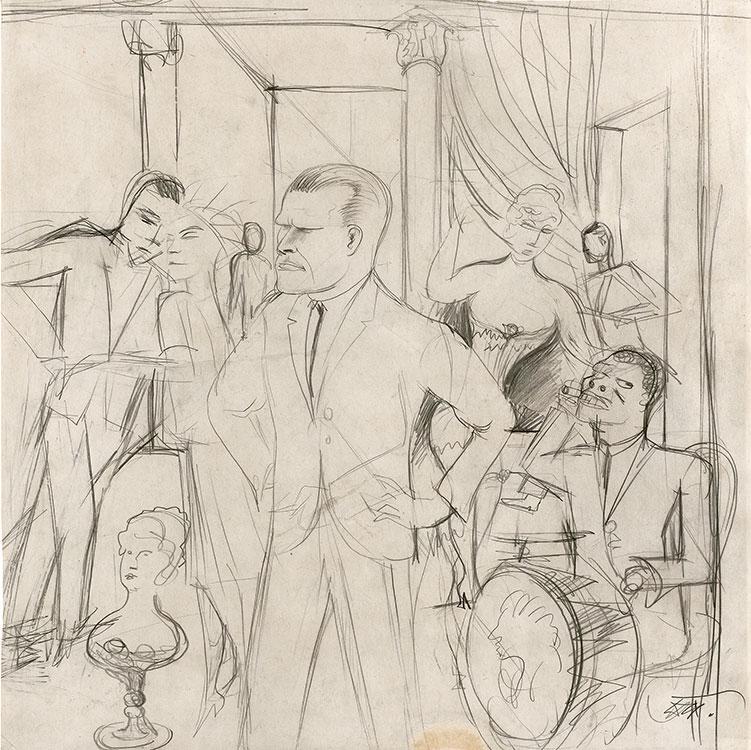

Drawing Modernity

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, drawing continued to play a seminal role in the creative process. Adolph Menzel, in keeping with his personal motto Nulla dies sine linea (Not a day without a line), was almost fanatical about exploring the visible world in his sketches. Similarly, nearly twenty thousand surviving sheets by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner demonstrate the artist’s urge to, in his own words, “draw to the point of madness.” Like their predecessors, these artists used drawing for unfettered explorations of new visual imagery; as a means of developing ideas for works in other media, such as paintings and prints; and to produce finished works of art. During the period of the Weimar Republic (1919–33), the Kupferstich-Kabinett actively acquired works by living artists, and many of the drawings on view here entered the museum’s collection shortly after their creation. The policies of the Nazi regime (1933–45), however, resulted in the confiscation and loss of many modern drawings that did not adhere to the cultural ideology of National Socialism and were deemed “degenerate.”

Adolph Menzel

These expressively charged studies stem from a trip that Menzel made to Italy in 1881. Rather than visit more popular destinations like Florence or Rome, the artist traveled to Verona, where he filled sketchbooks with firsthand studies of the characters and bustle of the city’s main market. Back in Berlin, Menzel used this visual repository as the basis for more elaborate drawings such as this one, made in preparation for his painting Piazza d’Erbe in Verona. The sheet is a superb example of Menzel’s mature style and his virtuosic control of the pencil, with which he was able to alternate fluently between broad, dynamic contour and refined details, confidently smudging the soft graphite to establish finely graded shadows.

Adolph Menzel

German, 1815–1905

Studies of a Crouching Man with Hammer and Chisel, 1883

Graphite pencil

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1886-10

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Photo: Herbert Boswank

Käthe Kollwitz

In 1844, several thousand weavers in the central European region of Silesia revolted against exploitative working conditions and decreasing wages. Kollwitz’s Weavers’ Revolt, a series of six prints completed in 1897, draws on these historic events but places them in a contemporary context. A preparatory study for the final image in the series, this drawing depicts the tragic consequences of the unrest. At left, men carry a corpse into a dark parlor, to be laid down next to the two dead bodies already there; a woman sits beside them, grieving. Although the revolt itself is left out of the image, the white gunpowder haze, which drifts into the interior space through the broken window, suggests that the fighting is ongoing.

Käthe Kollwitz

German, 1867–1945

The End, 1897

Graphite pencil, brush and pen and black and brown ink, heightened with white

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1918-21

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Herbert Boswank

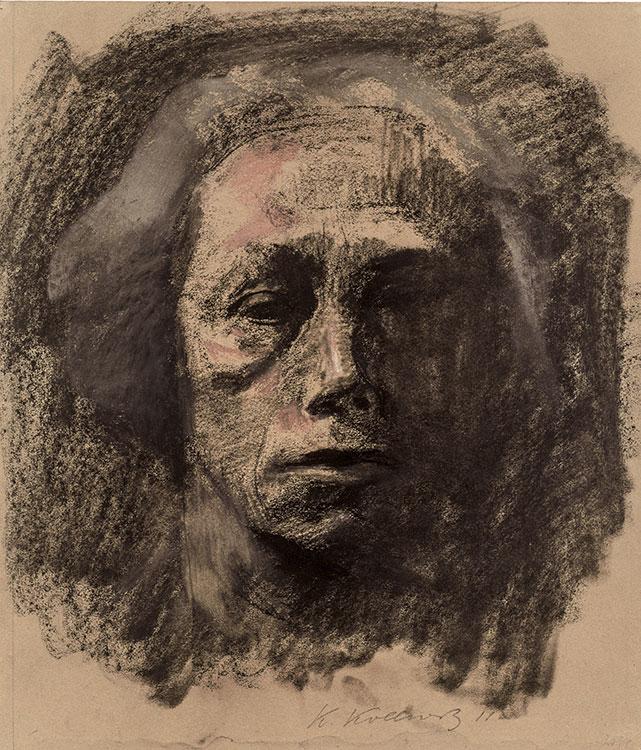

Käthe Kollwitz

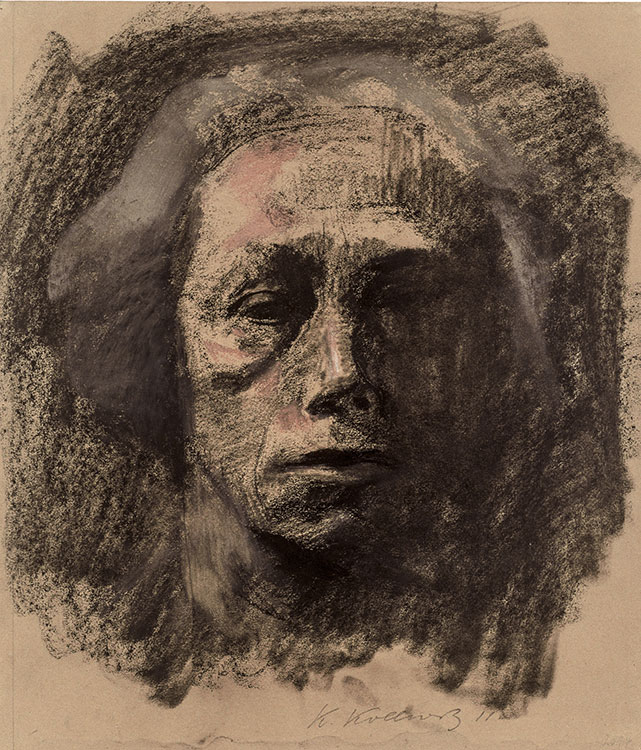

Between 1888, when she began her art studies in Munich, and her death in 1945, Kollwitz made scores of self-portraits in which she interrogated her appearance and her state of mind in a direct and uncompromising way. Although the deep rings surrounding her eyes and the gray hair can be interpreted as signs of aging, the artist was only forty-four years old when she made this work. The likeness is rendered predominantly in black chalk, with touches of violet accentuating her cheekbones and forehead. Covered in dense hatching, the left side of the artist’s face dissolves into the darkness and merges with the rapidly sketched background.

Käthe Kollwitz

German, 1867–1945

Frontal Self-Portrait, 1911

Black chalk, heightened with violet and gray chalk, with stumping, on grayish-brown paper

Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, INV. NO. C 1917-50

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Herbert Boswank

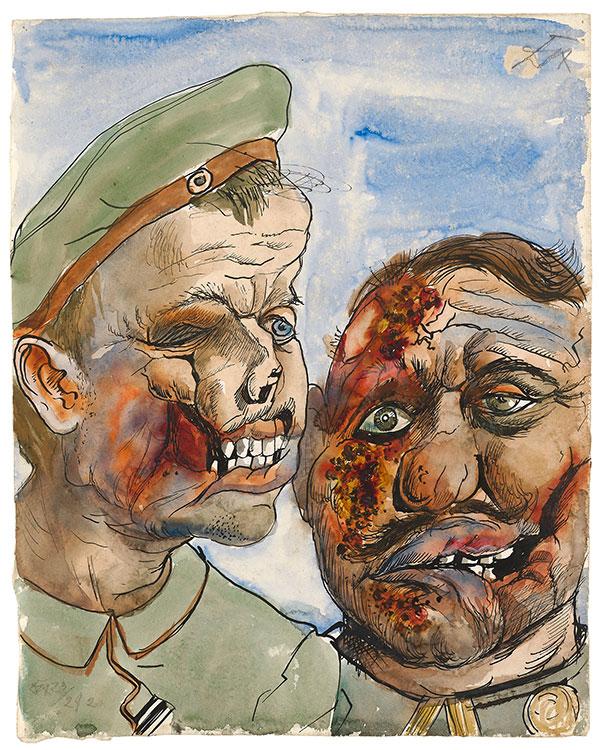

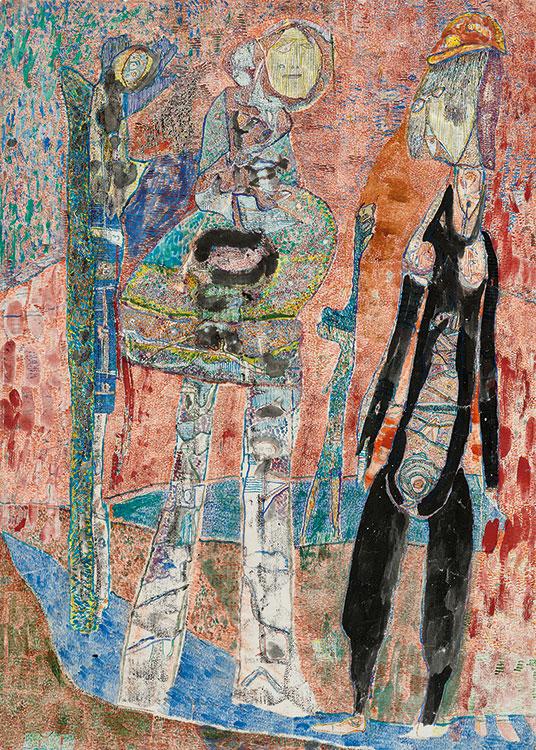

Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints