Imperial Cities

15th–16th Century

The term “free imperial city” (Reichsstadt) was coined in the fifteenth century, but the concept had roots extending back for centuries. Such cities were free from any territorial lord, secular or religious. They answered only to the emperor, who in turn granted the cities special privileges such as the right to mint coins, organize militias, and, most importantly, collect taxes and hold market fairs. Tied to vast commercial networks, these fairs enabled cities like Augsburg, Nuremberg, and Mainz to become hubs for skilled artisans, who produced luxury goods including books, both printed and handwritten. The development of these cities led to profound changes in patterns of artistic patronage, particularly when it came to making works for the open market. Imperial cities proudly proclaimed their status through a variety of visual media, from seals to public monuments. Their wealthy families competed with one another for attention in civic and religious arenas, all of which spurred artistic innovation and rivalry. Commerce and creativity went hand in hand.

Bible of Andreas of Austria

PRAGUE: A NEW CAPITAL

Named after its scribe, Andreas, this Bible was illuminated by four artists, a complex collaboration typical of court production in Prague during the reign of Emperor Wenceslas IV (r. 1376–1400). Its intended recipient was likely the scribe’s benefactor, William of Hasenburg (d. 1393), who had close ties to court and to the August-inian monastery at Roudnice nad Laben, the country seat of Prague’s archbishops. Marking the beginning of Genesis, the large initial I comprises seven medallions depicting Creation. The uppermost conflates the first and fourth days: the separation of light and dark and the creation of the sun, moon, and stars. The second roundel shows Earth, at center, surrounded by bands representing water and air. Together, the two medallions refer in schematic fashion to the cosmological system devised by Ptolemy (ca. 100–170), whose works were familiar at the court of Wenceslas due to the monarch’s obsessive interest in astrology.

"Bible of Andreas of Austria," in Latin

Written by Andreas of Austria for William of Hasenburg (d. 1393)

Czech Republic (Bohemia), Prague or Roudnice nad Laben, 1391

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.833, fols. 4v–5r

Purchased on the Belle da Costa Greene Fund, 1950

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

The flourishing court culture at Prague attracted scholars and craftsmen from all corners of the Empire. One such scribe, Andreas of Austria, names himself in the colophon he added to this giant bible, dated 1391.

Although Andreas did not write the entire bible himself, his having taken credit for the whole suggests that the volume was his gift to a patron. That patron may well have been William of Hasenburg, father of a future archbishop of Prague, who may have had ties to the nearby Augustinian monastery at Roudnice nad Labem, a country seat for the archbishops where the bible may have been made.

The large initial I for Genesis belongs to a type coined in the late eleventh century. Occupying six vertically disposed medallions (one for each day of Creation),the Hexameron towers above the figure of Christ-Logos enthroned among angels, resting on the seventh day. Such scenes of Creation usually run from bottom to top, like a stained-glass window, with God crowning the image. Here, however, the direction has been reversed.

Such Genesis initials offered opportunities for cosmological speculation. The uppermost medallion conflates the first and fourth days: the separation of light and dark and the creation of the sun, moon, and stars. Against a celestial background filled with angels, the Christ-Logos blesses a celestial orb on whose circumference sit the sun and moon. The sphere below, split into quadrants by large cracks, represents the four elements. In the second medallion, the Earth is surrounded by offset circles of water and air. Together, the two medallions refer in schematic fashion to the system devised by Ptolemy, whose works were familiar at the court of Emperor Wenceslas on account of his obsessive interest in astrology.

Leaf from the Seitenstetten Antiphonary

PRAGUE: A NEW CAPITAL

This leaf from a dismembered choir book exemplifies the “Beautiful Style” in Prague, associated with the court of Emperor Wenceslas IV. The initial for Christmas depicts the Virgin Mary kneeling before the Christ Child, surrounded by a mandorla of light. Both details relate to a vision of Christ’s birth experienced by St. Birgitta of Sweden (1303–1373). In the margin, a Benedictine monk imitates the Virgin’s pose, holding a scroll that reads “Pray for us to God.” The manuscript was likely part of a set donated to a Benedictine monastery by an unidentified patron, who must have come from the highest echelons of the court. His orange garments as depicted within another initial from the book (shown below) indicate that he was not a cleric.

Leaf from the “Seitenstetten Antiphonary,” in Latin

Czech Republic (Bohemia), Prague, ca. 1405

Cleveland Museum of Art

Andrew R. And Martha Holden Jennings Fund, 1976.100

Adoration of the Magi and Dormition of the Virgin

PRAGUE: A NEW CAPITAL

Painted in a style derived from Bologna, this diptych demonstrates Prague’s close ties to Italy. Emperor Charles IV corresponded with the humanist Petrarch and even brought him to the city. Prague’s humanists, among them Jan of Středy (1310–1380), chancellor to Charles IV, received their education in Padua and Bologna. On the left panel, the central magus, with the imperial eagle on his mantle, bears the distinctive features of Charles IV. In the Dormition, St. Peter’s threefold tiara identifies him as pope. The two wings of the diptych thus balance imperial and papal power. The pope to which the diptych refers would be Innocent VI (r. 1352–62).

Adoration of the Magi and Dormition of the Virgin

Czech Republic (Bohemia), Prague, ca. 1360

The Morgan Library & Museum, AZAZ 22

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1931

Prayer Book of George of Poděbrady

PRAGUE: A NEW CAPITAL

Commissioned by Joanna of Rožmitál (d. 1475) for her husband, King George of Poděbrady (1420–1471), this prayer book opens with a small image of the king at his devotions, at right. The page is nearly overwhelmed by the lush, old-fashioned border decoration, which includes five coats of arms identifying the king’s territorial holdings. Added a decade later, the full-page miniature of the Virgin and Child was painted by Valentin Noh, who based many of his compositions on engravings. The miniatures added to George’s prayer book testify to the increasing importance of prints as a means of disseminating ideas and to the lively interplay across different artistic media. The prayer book is written in Czech, unsurprising given the king’s Hussite sympathies.

"Prayer Book of George of Poděbrady," in Czech

Illuminated by Valentin Noh and the Master of the Schellenberg Bible

Czech Republic (Bohemia), Prague, 1466 and ca. 1470s

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.921, fols. 2v–3r

Gift of the Fellows, with funds from the Belle da Costa Greene Fund, 1965

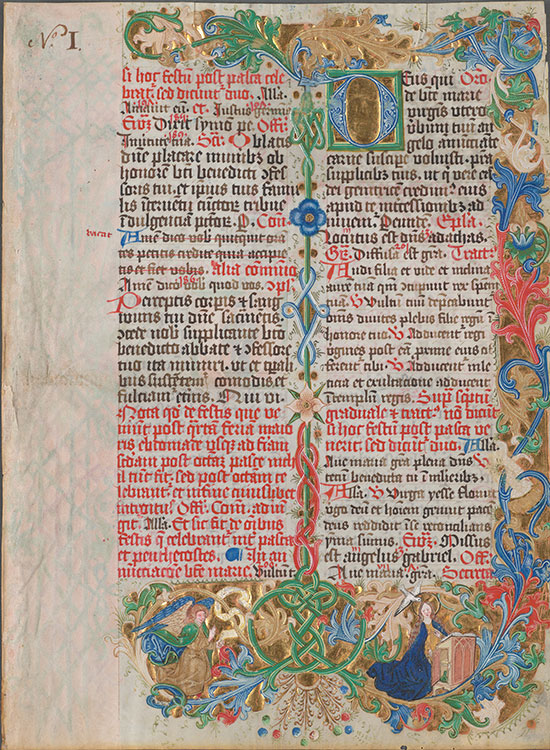

Office for the Feast of Corpus Christi

VIENNA: IMPERIAL RIVALRY AND HABSBURG AMBITION

Containing the prayers for the Feast of Corpus Christi, this manuscript was presented to Duke William of Habsburg shortly after his 1401 marriage to the Neapolitan princess Joanna of Anjou, whose arms appear at the center of the frontispiece’s lower register. Above, the kneeling duke, who wears a distinctive Rudolphine crown, adores the body of Christ in the facing initial. The attendant behind him is perhaps his privy notary, Leonhard Stubier (d. 1446), who may have commissioned the manuscript as a gift. Likely master and assistant, the book’s two artists worked in a cosmopolitan, courtly style characterized by conspicuous richness. The verdant meadow in which the duke kneels looks more like a luxurious millefleur tapestry than an inhabitable space.

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274)

Office for the Feast of Corpus Christi, in Latin

Illuminated by Nicholas of Brno and the Lyra Master for Duke William of Habsburg (1370–1406)

Austria, Vienna, ca. 1403–6

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.853, fols. 1v–2r

Gift of Louis M. Rabinowitz, 1951

Death of St. Clare

VIENNA: IMPERIAL RIVALRY AND HABSBURG AMBITION

This panel formed part a diptych, likely made for the aristocratic convent of Poor Clares in Vienna, and probably used in Masses for the dead. Depicted at the moment of her death and surrounded by female saints, St. Clare is compared to the Virgin Mary, whose death forms the subject of the second panel. In addition to the saints, two nuns are shown below in prayer. In its mannered delicacy and decorative brilliance, the panel represents the cosmopolitan court styles that marked the turn of the century, not only in Paris and Prague but also in Vienna. In addition to the punchwork that enlivens the gold ground, the painting includes striking passages in which colored varnishes emulate textile patterns.

Death of St. Clare

Master of Heiligenkreuz

Austria, Vienna (?), ca. 1400–1410

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1952.5.83

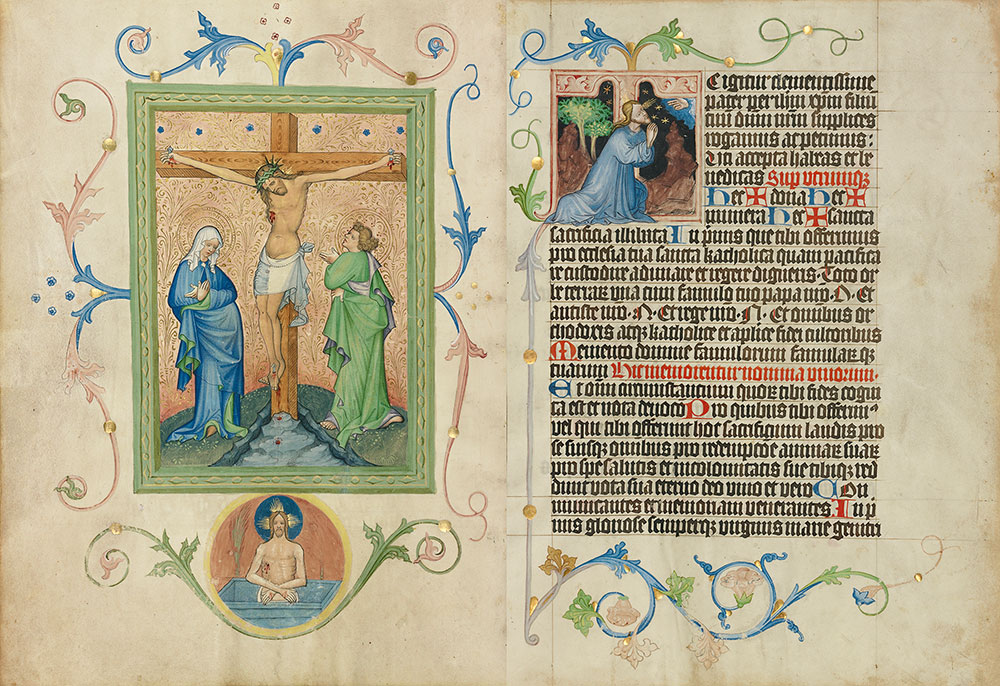

Missal for the Collegium Ducale

VIENNA: IMPERIAL RIVALRY AND HABSBURG AMBITION

This Mass book may have been commissioned as an imperial gift to the college of theology at the University of Vienna. In the Crucifixion, the figures of Mary and John are elongated and contorted, in dramatic contrast to the placid figure of Christ, whose blood flows copiously from his feet. Below the Crucifixion, a smaller image of Christ as the Man of Sorrows was intended for the priest to kiss during Mass. At right, an initial T marks the beginning of the Eucharistic prayer. The embedded depiction of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane omits any narrative elements, focusing solely on Christ in prayer. The facing miniatures were painted by two different itinerant artists who regularly collaborated on important commissions.

Missal for the Collegium Ducale, in Latin

Illuminated by the Master of the Kremnitz Stadtbuch and Master Michael

Austria, Vienna, ca. 1420–30

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS Ludwig V 6, fols. 147v–148r

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1983

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

As the seat of Habsburg rule, Vienna became an important artistic center. Its court, which included a powerful patrician class, its churches, and its university all had need for elaborately illuminated manuscripts. Commissioned in the early fifteenth century, this unusually large missal belonged to the Collegium Ducale, the college of theology at the University of Vienna. T

The opening on display stems from two artists. An anonymous craftsman contributed the Crucifixion of the left, whose prominent frame resembles a panel painting. The other artist, known only as Master Michael, painted the scene of the Agony in the Garden in the initial on the facing page. The scene is self-referential in that it provides the priest celebrating mass a model for his own prayer.

Set off by symmetrical acanthus in alternating blue and pink—a hall mark of both Bohemian and Austrian manuscripts of the period—the Crucifixion is paired with an osculatory of Christ as the Man of Sorrows, a small image for the priest to kiss during mass. In the main miniature, the figures of Mary and John are not only elongated and hipshot, but also contorted, in dramatic contrast to the placid figure of Christ. Although John turns his left shoulder to the viewer, his right hand, grasping his garment, occupies the foreground; his left arm, which wraps around his twisting torso, all but disappears, lending still greater emphasis to the almost disembodied hand gesturing toward the body of Christ.

Of the three figures, that of the dead Christ is the most restrained. His loincloth seems about to slip from his partially revealed groin. Christ’s blood flows copiously from his feet, forming not one, but two separate pools, as it drips down from one level of the rocky outcrop to the next. The motif implies that with time the blood will flow out of the image into the chalice on the altar.

Leaf from a Missal (MS M.936)

VIENNA: IMPERIAL RIVALRY AND HABSBURG AMBITION

The court style in Prague carried with it enormous prestige and was often emulated in Austria. Numerous artists from Prague also fled the city in the wake of the Hussite wars (1419–34), further contributing to the widespread influence of their art. The lyrical figural style of this miniature, as well as its abundant gold filigree, points to Bohemian models. The unknown artist, who may well have been Bohemian, also looked to sculptural models like the “Beautiful Madonnas” that were exported from Prague across central Europe. The artist transmutes the pain and violence of the Crucifixion into a poetic mood, enhanced by Mary’s direct gaze, entreating the viewer to share in her compassion.

Leaf from a Missal

Bohemia or Austria (?), ca. 1425

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.936

Bequest of Herman H. Lehman, 1968

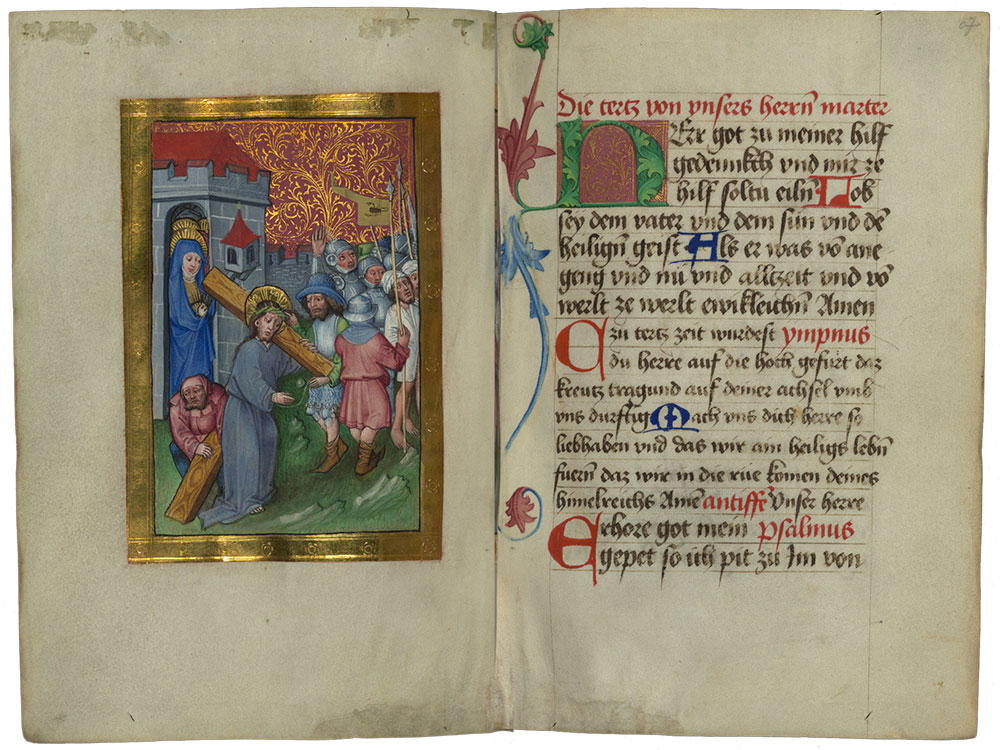

Book of Hours

VIENNA: IMPERIAL RIVALRY AND HABSBURG AMBITION

More than sixty manuscripts attest to the prolific career of the Master of the Maximilian Schoolbooks, who worked for a range of elite clients, including the University of Vienna and the court of Emperor Frederick III (1415–1493). The artist is named after a group of illuminated schoolbooks commissioned for the emperor’s son Maximilian I (1459–1519). While many of the book’s paintings have been removed and sold, it retains a miniature of Christ Carrying the Cross. The city gate frames the Virgin, at whose feet Simon of Cyrene bends to assist Christ with his burden. One of the soldiers turns back to push the Crown of Thorns onto Christ’s brow. In an excised miniature depicting the Nailing of Christ to the Cross, Christ looks down toward the skull marking the site as Golgotha (literally, “the place of the skull”). According to legend, the skull belonged to Adam; his son Seth planted a seed in the skull’s mouth that grew into the tree from which the cross was hewn.

Book of Hours, in German

Illuminated by the Master of the Maximilian Schoolbooks

Austria, Vienna, ca. 1465

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.764, fols. 66v–67r

Purchased, 1959

Leaf from the Same Book of Hours

Cleveland Museum of Art

Dudley P. Allen Fund, 1959.40

Leaf from an Antiphonary

MAINZ: ECCLESIASTICAL CAPITAL AND CRADLE OF PRINTING

Although little is known about its original context, this leaf once formed part of an antiphonary—a collection of chants—nearly identical to a set of choir books created around 1432 for the Carmelite monastery at Mainz. Those books were commissioned by Johannes Fabri, the son of a goldsmith and stepson of a butcher, who likely donated the set to mark his admission to the monastery, where he would eventually become prior. Instructions for creating the twisting, multicolored vine-scroll ornament survive in contemporary model books used by professional painters. Marking the beginning of a feast in Advent, the large initial M and its foliate decoration showcase exactly what the new technology of printing was not capable of doing.

Leaf from an Antiphonary, in Latin

Germany, Mainz, ca. 1430–50

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of Miss Alice M. Dike, in memory of her father, Henry A. Dike, 1928.225.2

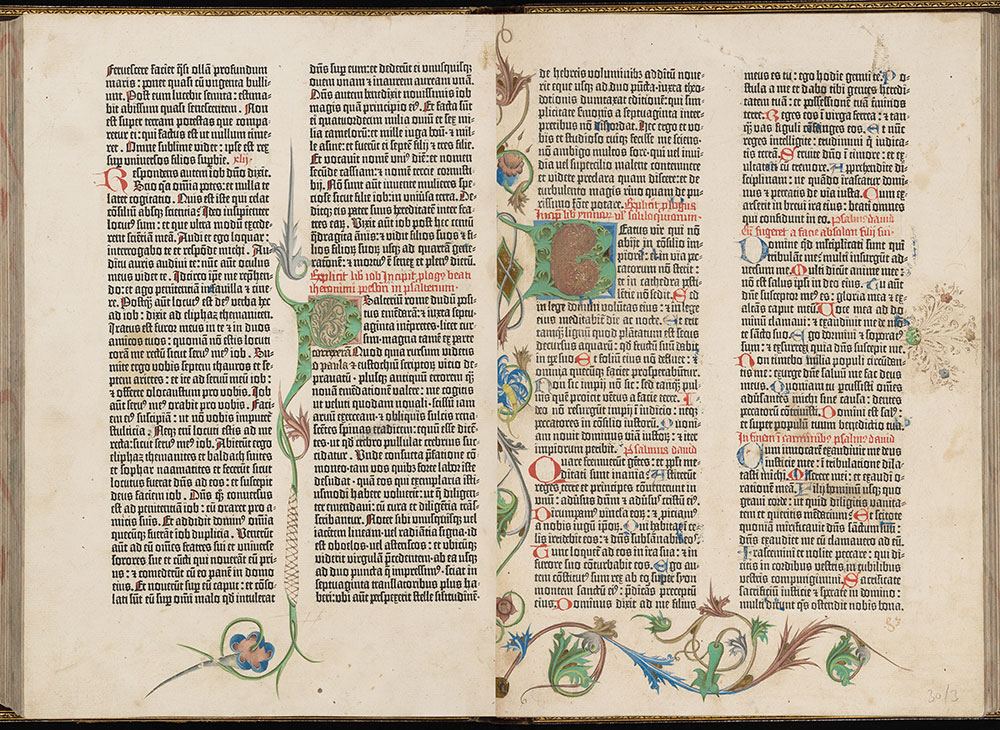

The Gutenberg Bible

MAINZ: ECCLESIASTICAL CAPITAL AND CRADLE OF PRINTING

The earliest mention of printed books in Europe is a 1455 letter sent to Emperor Frederick III (1415–1493), describing what must have been copies of the Gutenberg Bible for sale at the imperial Diet in Frankfurt. Several years earlier, Johann Gutenberg (ca. 1400–1468) had begun working with his financial backer, Johann Fust (d. 1466), to develop a printing press with moveable type (metal-cast letters), able to produce multiple copies of a text. Their now-famous two-volume Bible was issued in an edition of approximately 180 copies. Imitating the old-fashioned textura script of Gothic manuscripts, Gutenberg attempted to compete with deluxe, handmade commissions. In 1455, a bitter lawsuit ended Fust and Gutenberg’s relationship. The financier continued to run a successful press with Gutenberg’s former assistant, Peter Schoeffer (d. 1503). Later adapted to contain just the Old Testament, this unique copy of Gutenberg’s Bible served as the model for Fust and Schoeffer’s 1462 Bible. Its illumination was added around that time by an artist from Mainz who worked exclusively in Fust’s workshop.

Gutenberg Bible, in Latin

Mainz: Johann Gutenberg & Johann Fust, ca. 1455

The Morgan Library & Museum, PML 12, fols. 292v–293r

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan with the Irwin Collection, 1900

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

Mainz was the largest and most powerful archbishopric in central Europe. Its archbishop

became not simply one of the ecclesiastical electors, but also archchancellor of the Empire, with the right to convene and lead elections of the king of Germany. Gutenberg, a citizen of Mainz, set up his print shop there no later than 1450 and by 1455 the Gutenberg Bible, the first Western book printed from moveable type, was published in approximately 160 to 180 copies.

Gutenberg’s investment in the production of a large-format folio bible was hardly self-evident. Despite the paramount importance of the text, the market for complete bibles, as opposed

to liturgical books, was limited.

The Morgan Library, exceptionally, holds three copies of the Gutenberg Bible, two of them complete. One of these belongs to the limited number printed on vellum; another belongs to the majority that were printed on rag-linen paper.

The Morgan’s third copy, exhibited here, is unusual on several counts. Unlike most copies of the Gutenberg Bible, which split the text evenly across two volumes at the end of the Psalms, this copy comprises just the Old Testament in a single volume—likely a later modification. Twenty-two of its pages feature a unique set of replacement type settings, which indicate that the copy was produced at the very end of the print run. Finally, it also contains the earliest extant compositor’s marks (typesetters’ indications of pagination) introduced when it was used as a model by Fust and Schoeffer, formerly Gutenberg’s financial backer and apprentice, respectively, to print their own bible in 1462.

In copies of the Gutenberg Bible, most of the decoration had to be added by hand and remains modest compared to sumptuous illuminated manuscripts of the period, which competed with printing by supplying precisely what printers were not in a position to provide—namely, elaborate imagery in brilliant color.

Gospel Book

MAINZ: ECCLESIASTICAL CAPITAL AND CRADLE OF PRINTING

The Evangelist portraits in this Gospel book have traditionally been attributed to the so-called Housebook Master. However, this artistic personality is better understood as a group of artists active along the Middle Rhine. Their miniatures respond to developments in contemporary panel painting, particularly from Flanders, as demonstrated in this portrait of the evangelist Matthew, which features a clearly constructed space with receding floor tiles and obliquely placed objects that cast shadows. Also telling in this regard is the absence of extensive border decoration. By the mid-fifteenth century, manuscript illumination had to compete not only with panel painting but also with printing.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Illuminated by circle of the Housebook Master

Germany, Middle Rhine, ca. 1475–80

Cleveland Museum of Art

Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund, 1952.465

Leaf from the Simmern Missal

MAINZ: ECCLESIASTICAL CAPITAL AND CRADLE OF PRINTING

Another artist from the Housebook Master group painted this Crucifixion miniature from the missal of Duke Friedrich and Margarethe, elector and electress Palatine. The scene plays out against a dramatic, sweeping landscape. The stiff, still body of Christ contrasts with the contortions of the good and bad thieves surrounding him. What really catches the eye, however, besides the glittering coat of arms at the foot of the cross, is the vivid coloring of the clothed figures and the sensitive treatment of atmosphere. The fictive frame heightens the sense of a panel painting reproduced within the confines of a book.

Leaf from the "Simmern Missal," in Latin

Illuminated by circle of the Housebook Master

Germany, Middle Rhine, ca. 1481–82

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Robert Lehman Collection, 1975.1.2479

History of Alexander the Great

AUGSBURG AND BAVARIA

This manuscript comprises religious and historical texts in German, including History of Alexander the Great by the physician Johannes Hartlieb (ca. 1410–1468). Written on paper in a Swabian dialect by the scribe Völckhart Landsperger, the texts were chosen to suit the interests of a particular patron. Many such scribes worked as city notaries, providing a close link between civic culture and literary production. Despite the inexpensive materials, the lively pen drawings are detailed and rich in narrative. In this example, Alexander visits a beautiful mountaintop temple. Its staircase is made of gemstones supported by golden chains, a characteristic example of the text’s many wonders. The work of several artists, the book exemplifies the increasing number of paper manuscripts produced for the growing patriciate and merchant classes in Augsburg.

Miscellany, Including Johannes Hartlieb’s History of Alexander the Great, in German

Written by Völckhart Landsperger

Germany, Augsburg, ca. 1450–60

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.782, fol. 292r Purchased, 1934

Missal of Johannes von Giltlingen

AUGSBURG AND BAVARIA

This leaf comes from a deluxe Mass book illuminated for the abbot of the imperial Benedictine abbey of Sts. Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg. As a center of the Melk monastic reform movement, the abbey produced books of all kinds. In addition to scribal, authorial, and artistic activity, the abbey housed its own press, complete with a binding workshop. Shown here is the Mass for the Feast of the Annunciation. Its accompanying miniature is not placed within the initial, as was customary, but within the foliage in the lower margin. The artist was a monk, whose brother, Leonhard Wagner, also affiliated with the monastery, was a celebrated scribe and writing master.

Leaf from the “Missal of Johannes von Giltlingen,” in Latin

Illuminated by Conrad Wagner for Johannes von Giltlingen (d. 1496)

Germany, Augsburg, 1484–85

Columbia University, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, New York, MSMS Plimpton 36B

Bifolio from a Confraternity Book

AUGSBURG AND BAVARIA

Known today primarily for his success in the early print trade, Johann Bämler began his career as a scribe and an illuminator. Featuring miniatures of the Crucifixion and St. Leonard, this bifolio, his earliest known work, once belonged to a charitable confraternity devoted to the saint. The surrounding rose-colored frames bear verse inscriptions. On the left, Bämler signed and dated the work. The prayer on the right invokes Leonard as the patron saint of prisoners seeking liberation. Working for a range of clients, Bämler’s industrious workshop captures the commercial spirit of book production in Augsburg.

Bifolio from a Confraternity Book, in Latin

Illuminated by Johann Bämler (ca. 1430–1504)

Germany, Augsburg, 1457

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.45

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1902

Twenty-Four Elders

AUGSBURG AND BAVARIA

Deluxe manuscripts of the later fifteenth century often feature conspicuously large miniatures, as if rivaling panel paintings in their dimensions. As part of ambitious programs of illustration, such miniatures could distinguish a particular commission from a more standard production. This miniature derives from the most sumptuous of the surviving 169 copies of Otto von Passau’s Twenty-Four Elders—a compilation of excerpts from many authors, organized around devotional themes linked to each of the titular elders. The fifth elder is shown as a gray-bearded king, with book in hand as if an author portrait. The miniature is manifestly the work of a panel painter, underscoring the extent to which illuminators looked to other media as a source of inspiration.

Leaf from Otto von Passau's Twenty-Four Elders

Illuminated by the Master of the Munich Marian Panels

Germany, Bavaria, ca. 1450

Free Library of Philadelphia

Rare Book Department, Lewis E M 44:12

Annunciation

AUGSBURG AND BAVARIA

Attributable to a Bavarian artist, this panel of the Annunciation demonstrates the interrelationships between illuminators and panel painters. Following Netherlandish examples, the scene is set in a domestic interior depicted with sparkling luminosity, which bathes the scene in supernatural as well as natural light. Above the door through which the angel Gabriel enters, a Hebrew scroll reads “before” or “not yet” (b’terem), which refers here to the pending birth of Christ as the fulfillment of Jewish prophecy. Gabriel notifies Mary of the Incarnation using a charter with three seals (a reference to the Trinity), a motif found most often in Bohemian painting.

Annunciation

Germany, Bavaria (?), ca. 1450

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of Julie and Lawrence Salander, in honor of Keith Christiansen, 2005.103

Starck Triptych

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

Commissioned by the Nuremberg patrician Georg Starck, this triptych was painted by an artist in the circle of Hans Pleydenwurff and Michael Wolgemut, in whose workshop Albrecht Dürer was trained. Representing the Elevation of the Cross, an unusual subject for the time, the crowded scene is set against a continuous landscape, which shapes the procession to Golgotha. Under the bright sky, at Christ’s privileged right side, the Virgin, Veronica, and the grieving Magdalene gather. Under the dark clouds at Christ’s left are the witnesses, such as the mounted centurion who gestures to Christ and the thief with his arms tied behind his back, contemplating the rough-hewn cross on which he, too, will be hoisted.

"Starck Triptych”

Master of the Starck Triptych

Germany, Nuremberg, 1480–90

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 1997.100.1.a

The Nuremberg Chronicle

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

Structured around the seven ages of the world, from Creation to the Last Judgment, the “Nuremberg Chronicle” stands in the long tradition of universal chronicles, many of which also highlight the importance of a specific city. Deliberately placed at the beginning of the sixth age, the Christian era, this view of Nuremberg presents the city as the New Jerusalem. At left are the towers of its most important parish churches: St. Sebald and St. Lawrence. The Women’s Gate occupies the left foreground, with its double-headed eagle identifying Nuremberg as an imperial city. A stele occupies the foreground alongside a group of three crosses. These features, together with the raised platform to the right, where criminals were beheaded, mark the site as a place of execution. Salvation for some presumed punishment for others.

Hartmann Schedel (1440–1514)

Woodcuts by workshop of Michael Wolgemut (1434–1519)

Liber chronicarum (“Nuremberg Chronicle”), in Latin

Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1493

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Paul Mellon Collection, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1991.7.1, fols. 99v–100r

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

Of the Free Imperial Cities, none is better known than Nuremberg, and no artifact associated with it more famous than the extensively illustrated world history known as the Nuremberg Chronicle, compiled by the physician and Italian-trained humanist Hartmann Schedel. An immensely ambitious work, the Chronicle was commissioned by the Nuremberg merchants Sebald Schreyer and his son-in-law, Sebastian Kammermeister, and published in 1493 by Anton Koberger. The original edition was in Latin, shortly followed by a German translation.

Structured around the seven ages of the world, spanning from Creation to the Last Judgment, the Chronicle stands in the tradition of earlier universal chronicles, many of which were heavily illustrated and also carried world history forward to highlight the importance of a specific city.

Comprising over 1,800 woodcut illustrations, printed from 645 blocks, the Chronicle’s extensive visual program was executed under the supervision of the painter Michael Wolgemut, whose workshop Albrecht Dürer was trained.

Among the Chronicle’s most famous illustrations are the spectacular city views, particularly that of Nuremberg, for which a deliberate effort was made to ensure that the city—originally planned for later in the volume—would be positioned instead toward the beginning of the sixth

age, which starts with the birth of Christ. Nuremberg thus appears as the New Jerusalem.

As was common in the art of the period, the Chronicle’s city views combined precise observation with conventional motifs, both of which contribute to the making of meaning. The view of Nuremberg—the only one that fills a two-page spread to the exclusion of the main text—impresses on account of its selective accuracy. At right center, atop a high bluff at the northern periphery of the city, stands the Burg, or imperial castle, which often hosted visiting German kings and emperors. To the left can be seen the twin towers of the church of St. Lawrence, for which the Geese Book, exhibited nearby, was made.

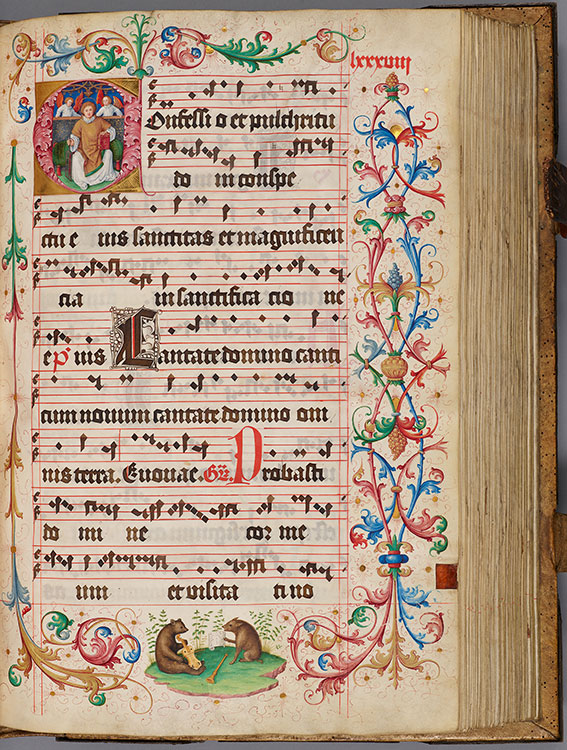

Geese Book

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

Prominent members of the parish of St. Lawrence in Nuremberg donated this massive two-volume gradual to their church. The imposing manuscript is known as the “Geese Book” after a humorous, self-referential scene of a wolf teaching a gaggle of geese to sing from a choir book on a podium, as a wily fox attacks them rom behind. Anton Kress (1478–1513), a member of the city council and relative of Willibald Pirckheimer, a humanist in Dürer’s circle, oversaw the manuscript’s production. Although working at a time when Dürer was the dominant artistic personality in Nuremberg, Jakob Elsner produced work that shows little debt to Dürer’s style. In the lower margin of the Feast of St. Lawrence, on view here, the shawm (woodwind instrument) lying on the ground may refer to the former braying of the swine who now sings the “new song” (canticum novum, mentioned in the opening words of the feast) while a bear plays a viol. The original pigskin binding, with metalwork from Nuremberg’s leading metalworker, is typical of German books of this period.

“Geese Book.” The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.905, vol. 1, fol. 186r (detail).

"Geese Book," in Latin

Illuminated by Jakob Elsner

(ca. 1460–1517)

Germany, Nuremberg, ca. 1507–10

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.905, vol. 2, fols. 87v–88r

Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, December 1962

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

Made for the church of St. Lawrence in Nuremberg in the early sixteenth century, this enormous manuscript is but one of two volumes known as the Geese Book after a whimsical, self-referential marginal image of a wolf teaching a choir of geese to sing from a choir book on a podium, while a wily fox attacks them from behind.

Other folios, such as that exhibited here, also contain satirical animal imagery. In the margin of the feast for St. Lawrence, the church’s titular saint, the shawm lying on the ground may refer to the former braying of the swine who now sings the “new song” mentioned in the accompanying chant from a sheet of music while a bear plays a viol.

A hugely ambitious project, the Geese Book was initiated by Sixtus Tucher, a member of one of the city’s leading patrician families. Tucher’s successor, Anton Kress, a member of the city’s inner council and a distant relative of the humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, Albrecht Dürer’s close friend, oversaw the bulk of its production.

The gradual was written by a vicar of the church, Friedrich Rosendorn, who is named in the volumes’ colophons. Jakob Elsner, however, the artist to whom the gradual’s decoration is attributed, goes unmentioned.

Commissions of grand manuscripts such as the Geese Book would in large part be made redundant, both by the growing predominance of printing and the spread of the Protestant Reformation, which, in keeping with the theology of Martin Luther, stressed salvation by faith alone, not by good works, which often took the form of the patronage of magnificent works of art. In this respect, the Geese Book, a product of the imperial city of Nuremberg, harks back to the grand imperial commissions of the earlier Middle Ages.

Recording from the Geese Book

“Mass for Saint Lawrence”

Das Gãnsebuch (The Geese Book), Schola Hungarica

℗ & © 2005 Naxos Rights International Ltd.

Cuttings from the Missal of Johann Stantenat

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

At some point in the nineteenth century, five cuttings from a two-volume missal were artfully arranged to form this collage. The missal was commissioned by the abbot of the Cistercian abbey at Salem, southwest of Nuremberg. At center, St. Benedict stands within a large initial O that begins the Mass for his feast day. Clad in the black habit of the Benedictines, he holds a crozier and a miraculous glass vase. By adopting the same attributes for the portrait of Abbot Stantenat above, the artist equates him with the saintly model. Below are the arms of Salem Abbey and Abbot Stantenat on either side of a crozier bearing the manuscript’s date.

Cuttings from the “Missal of Johann Stantenat”

Illuminated by the workshop of Jakob Elsner

(ca. 1460–1517) for Abbot Johann Stantenat (d. 1494) of Salem Abbey

Germany, Nuremberg, 1491

Art Institute of Chicago

Gift of Sandra Hindman, 2017.206

Leaf from a Missal (MS 52)

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

Although the narrative of the Crucifixion calls for a view of Jerusalem seen from Golgotha, the city in the background of this miniature appears to be Nuremberg. In its meticulous rendition of topographical details, the miniature rivals the drawings and watercolors that Albrecht Dürer produced while crossing the Alps on the first of his two trips to Italy (1494–95), sights from which he also incorporated into religious and allegorical subjects. Here, such details include the gabled façade of Nuremberg’s Church of Our Lady, directly behind St. John. Designed by Peter Parler, the architect of Prague Cathedral, the church was built between 1352 and 1362 by Charles IV on the site of Nuremberg’s old synagogue.

Leaf from a Missal

Illuminated by the Pleydenwurff-Wolgemut Workshop

Germany, Nuremberg, ca. 1475–1500

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS 52

Purchased, 1993

Leaf from the Hohenlandenberg Missal

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

This Crucifixion scene once formed part of an immense, four-volume missal commissioned by Hugo von Hohenlandenberg, bishop of Constance. The illumination is the work of an unknown artist closely associated with Albrecht Dürer. The figures are nestled within a landscape, in which the echoing forms of the winding river and road generate a continuous recession toward the horizon. The manuscript’s patron—the bishop—kneels in the foreground with his arms occupying the lower margin. Like many of his elite peers, he fought continuously with the citizens of his city over issues of legal jurisdiction and finance, a struggle that led to his forced abdication in 1529.

Leaf from the “Hohenlandenberg Missal”

Illuminated by the Master of the Hohenlandenberg Missal for Bishop Hugo von Hohenlandenberg

(1460–1532)

Germany, Nuremberg or Constance, ca. 1510

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.955

Purchased as the Gift of the Fellows, with the Special Assistance of Four Members of the Board of Trustees, Mrs. Gordon S. Rentschler, and Mrs. G. P. Van de Bovenkamp (Sue Erpf Van de Bovenkamp) in Memory of Armand G. Erpf, 1973

Theuerdank (Noble Thought)

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

Written by courtiers of Emperor Maximilian I, the Theuerdank (Noble Thought) tells the allegorical story of a knight, understood to be a thinly disguised stand-in for the emperor. Along with the text, printed in an early Fraktur typeface, the book incorporates 118 woodcuts—all by pupils or followers of Albrecht Dürer. Here, the protagonist rides an unruly horse given to him by his nemesis in the hope of killing him. The hero barely manages to bring the steed under control before it plunges into the castle’s moat, shown as a river. An instrument of imperial propaganda, the book also serves as a gallery of the period’s leading graphic artists.

Melchior Pfintzing (1481–1535) and Marx Treitzsaurwein (ca. 1450–1527) Woodcuts by Leonhard Beck (1480–1542), Hans Schäufelein (ca. 1480–1540), and Hans Burgkmair (1473–1531)

Theuerdank (Noble Thought), in German

Augsburg: Hans Schönsperger, 1517

The Morgan Library & Museum, PML 20623

Emperor Maximilian I

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

Hans von Hungerstein (1460–1503) had this depiction of Emperor Maximilian I as an ideal knight added to his personal copy of a popular chronicle of the city of Strasbourg by Jakob Twinger von Königshofen (1346–1420). Like the “Nuremberg Chronicle,” Twinger’s account situates Strasbourg within the histories of the world, emperors, popes, and the diocese. Hungerstein’s additions represent Maximilian’s coronation in 1486 as king of the Romans as a historical milestone. Seated on horseback like the legendary hero St. George, and surrounded by imperial coats of arms, Maximilian embodies the archetype of Christian and courtly manhood, no doubt how von Hungerstein, himself a knight, sought to be remembered.

Master of the Strasbourg Chronicle

Emperor Maximilian I

Strasbourg, 1492

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Woodner Collection, Gift of Andrea Woodner, 2006.11.16

Conrad Celtis, Four Books of Love

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

Albrecht Dürer collaborated with the humanist Conrad Celtis on this patriotic work of pedagogy, which represents Germany as the legitimate inheritor of Greco-Roman learning. Celtis praised Dürer as a new Apelles (a famous ancient Greek painter). In the frontispiece at left, Dürer places his monogram, AD, at the base of the obelisk standing before Philosophy. Thus he joins the sages in the medallions who represent the cumulative wisdom of Egyptians, Chaldeans, Greeks, Romans, and the Germans. The Greek letters on the obelisk represent the seven liberal arts and form the ladder by which one ascends to Wisdom. Representing the winds, the four heads in the corners also stand for the four elements and the four bodily humors.

Another of Dürer’s woodcuts for Conrad Celtis’s book takes the form of a traditional presentation scene. Holding the wreath of a poet laureate, Celtis presents a copy of his book to Maximilian I. The enthroned emperor sits below the imperial eagle and the distinctive imperial crown. The frame employs classically inspired garlands, which in their abundance carry connotations of cornucopia (bountiful prosperity). The inscription adapts a passage from Exodus 21: “He that curseth his father [here, the emperor] shall die the death.”

Conrad Celtis (1459–1508)

Woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and others

Quatuor Libri Amorum

(Four Books of Love), in Latin

Nuremberg: Sodalitas Celticae, 1502

The Morgan Library & Museum, PML 23296

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1906

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Bequest of James Clark McGuire, 1931.54.59

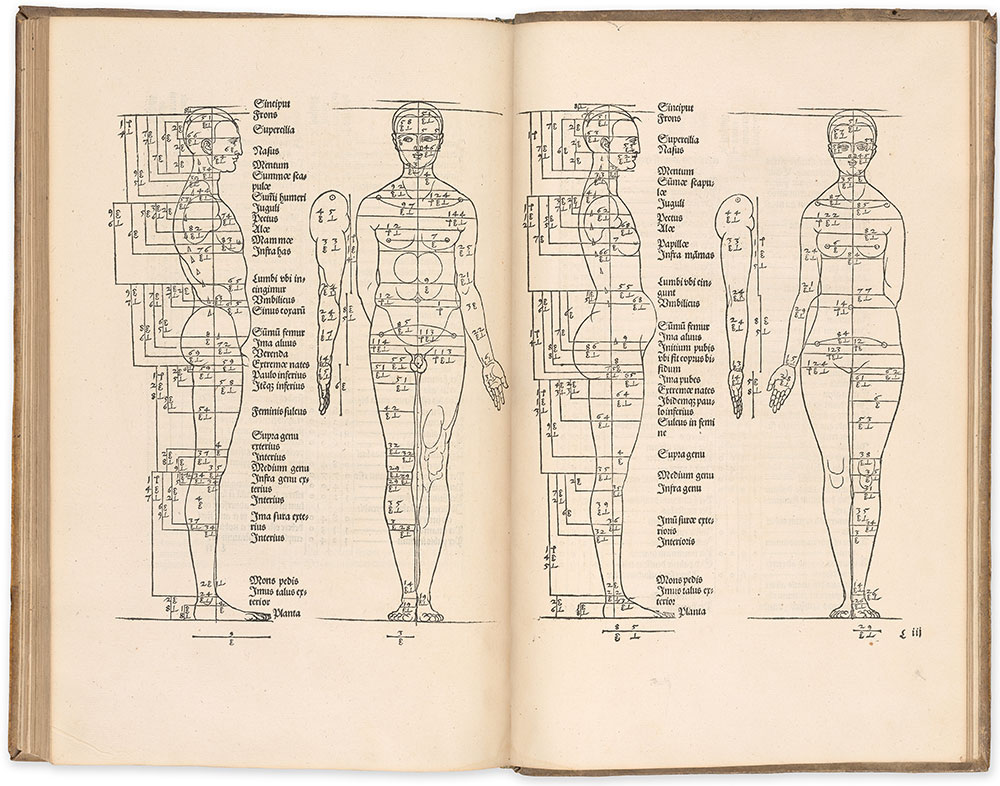

Four Books on Human Proportion

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

Dürer’s posthumous treatise on proportions codified his approach to the representation of the human body. With the volume’s roughly 150 woodcuts, including full-length studies of men and women in a variety of poses, the artist demonstrated his belief that the human body could be reduced to basic geometrical forms (lines, areas, and solids). Rather than following strict standards of idealized beauty, Dürer expanded his analysis to include various physiques of people of all sizes and ages, including children, at rest or in motion. Dürer first engaged with the topic of proportions following his travels to Italy, where artist-theorists such as Leon Battista Alberti and Leonardo da Vinci had worked extensively on the subject.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

De varietate figurarum (Four Books on Human Proportion), in Latin

Nuremberg: Agnes Dürer, 1532 and 1534

The Morgan Library & Museum, PML 77029

Gift of Mr. John P. Morgan II in memory

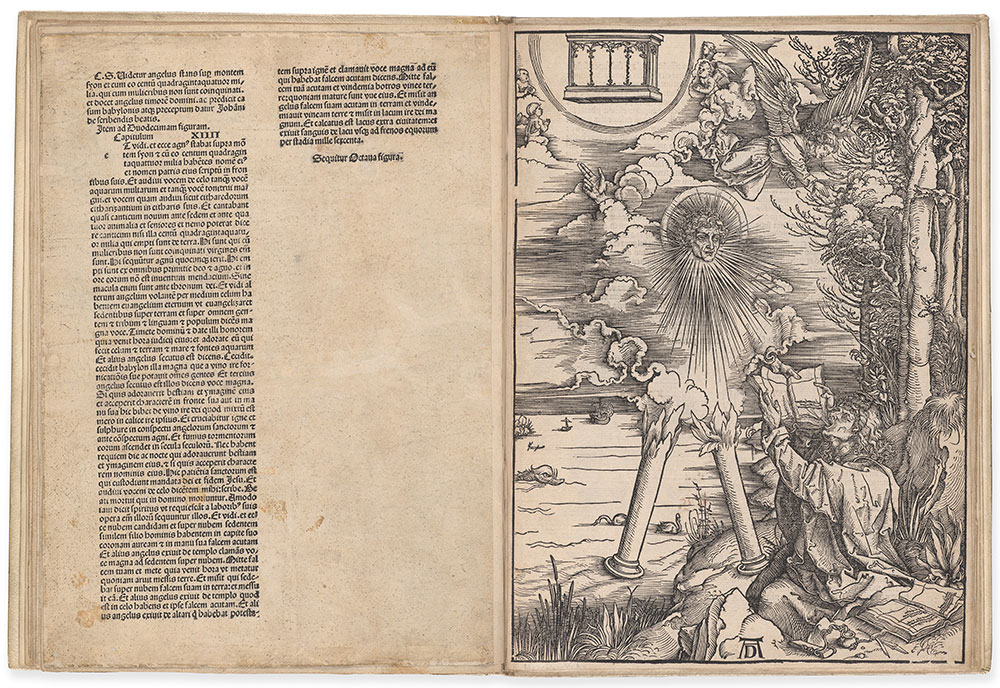

Albrecht Dürer, Apocalypse with Pictures

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

The Apocalypse with Pictures represents Dürer’s first major book project. First published in 1498, just prior to the Jubilee Year of 1500, it represents a self-conscious declaration of artistic genius that helped him secure international fame. Dürer’s woodcutting technique incorporates refinements associated with engraving, such as tapering lines and complex crosshatching, enabling dramatic lighting and psychological nuance. The image of John the Evangelist eating a book from an angel, at right, demonstrates the visionary effect of the artist’s innovations. The biblical text describes the angel as having one foot in the sea and the other on land, “clothed with a cloud,” and with a “face as the sun, and his feet as pillars of fire.” While faithful to the source, Dürer reimagined the scene with startling vitality.

Dürer created a new title page, above, for this second edition of his Apocalypse in 1511. Underscoring the visionary nature of the text, the scene takes place in a celestial realm. John the Evangelist takes inspiration from the Virgin and Child as he writes in his book. In addition to title pages, Dürer created colophons for his books—formal statements prohibiting anyone from copying them or their prints, and declaring his work protected under imperial privilege.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

Apocalipsis cum figuris (Apocalypse with Pictures), in Latin

Nuremberg: Albrecht Dürer, 1511

Columbia University, Rare Book & Manuscript

Library, New York, BOOKART NC251.D93 1511 B47

Title Page with the Virgin and St. John

Germany, Nuremberg, 1511

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of Mrs. Felix M. Warburg, 1940139.6(1)

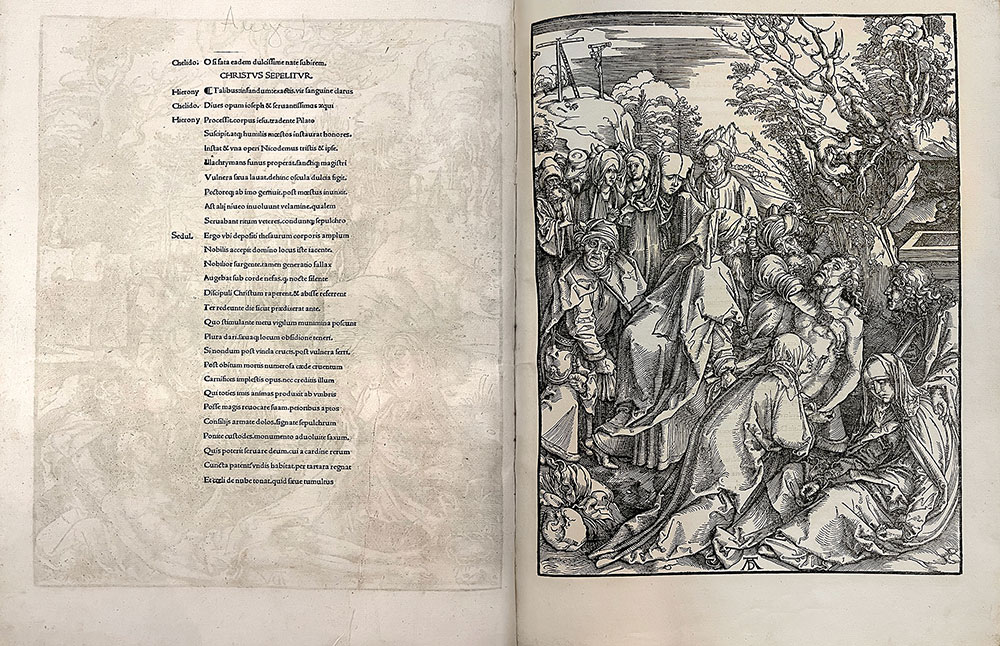

Albrecht Dürer, The Large Passion

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

For Dürer, 1511 marked a period of intense engagement with commercial projects. Following on the success of his Apocalypse with Pictures, reissued that year, he produced devotional picture books designed in the same format, juxtaposing text and image on facing pages. These include the Small Passion, the Large Passion, and the Life of the Virgin—the latter two combined with the Apocalypse in this single volume, which was bound in Nuremberg and belonged to a house of pious Franciscan laywomen in Munich. With these books, Dürer created work not for a commissioning patron but for the open market. To accompany his woodcuts, he commissioned Latin poems from the humanist scholar, poet, and monk Benedict Chelidonius. Shown here, at right, is the Entombment. The tomb, however—only partly visible at the right—is tucked into the background, as is the mount of Golgotha, at upper left, whereas in the foreground, the focus remains on the mourning of Christ’s followers and disciples. The print thus both evokes a narrative continuum and invites a powerful emotional response.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Benedict Chelidonius (ca. 1460–1521)

Passio Domini Nostri Iesu (The Large Passion), in Latin

Nuremberg: Albrecht Dürer, 1511

New York Public Library, Spencer Collection

Ger. 1511

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

Albrecht Dürer’s exposure to printed books was no doubt facilitated through his godfather Anton Koberger, Germany’s most successful publisher, whose press produced the Nuremberg Chronicle among other notable works. Koberger likely had a hand in the production of the artist’s first major book project—the Apocalypse with Pictures, published in 1498 in Latin and German editions. Over a decade later, in 1511, Dürer returned to independent book projects.

Picking up on the commercial success of his Apocalypse, which he reissued that same year, he produced three more devotional picture books designed in the same novel format, juxtaposing text and full-page images across a single opening. Never before had a printed book given such prominence to pictures.

Of these books, he referred to the Large Passion, the Life of the Virgin and the reprint of the Apocalypse as his “three great books,” in reference to their large folio format. The fourth book—his Small Passion—was produced in a much smaller octavo format. With his three great books, Dürer was creating work not for a commissioning patron but rather the open market. To accompany his woodcuts, Dürer commissioned texts from the humanist scholar, poet and monk Benedict Chelidonius. Writing in a classicizing style befitting Dürer’s elite humanist audience, Chelidonius provided Horace-like odes for the Small Passion, epic verse for the Large Passion, and elegiac couplets for the Life of the Virgin.

The three great books were often sold and bound together, as in the example shown here. The value of prices is difficult to judge for this period, but generally Dürer’s three Large Books sold for a quarter Gulden each, about the cost of a nice pair of shoes. This copy’s fine leather binding, which would have been added later and at the owner’s expense, is typical of sixteenth-century Nuremberg. This copy once belonged to the important library of the St. Pütrich cloister in Munich, a house of devout Franciscan laywomen.

Hybrid Prayer Book (MS M.1218)

NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

Dürer’s picture books had a profound impact on the form and content of deluxe prayer books. Entire sets of his prints were often recombined with handwritten prayers to create new hybrid manuscripts, a phenomenon particularly associated with the sixteenth century. Comprising, at its core, seventeen prints from Dürer’s Engraved Passion (1507–13), this manuscript was written and illuminated by the imperial scribe, artist, and notary Hieronymus Oertel, who ran a workshop creating such books for Nuremberg’s wealthy burghers. Each of the hand-colored engravings is accompanied by a corresponding prayer in German. The elaborate gilt borders framing each page, carefully placed over the edges of the engravings, mask the transition from print to parchment.

Prayer Book, in German

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Hieronymus Oertel (1543–1614)

Germany, Nuremberg, 1507–13 and ca. 1580–1600

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.1218

Purchased on a grant provided by the Bernard H. Breslauer Foundation, with the Harper and Seligman Funds, and as the gift of Virginia M. Schirrmeister and a second, anonymous, member of the Visiting Committee to the Department of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in memory of Melvin R. Seiden, 2020