Imperial Monasteries

12th–14th Century

As monastic reform movements gained momentum throughout the empire, the tenuous relationship between emperor and pope, so carefully maintained by Carolingian and Ottonian rulers, devolved into outright hostility. The trigger was the matter of investiture, the practice of appointing new bishops or abbots. For centuries, emperors and kings reserved the right to install their own candidates in important clerical positions within their realm. However, with the increasing strength of the papacy, along with a growing sense that bishops should not be active in imperial politics, this traditional right became untenable. The ensuing Investiture Controversy (ca. 1076–1122) resulted in a significant weakening of imperial power and a related strengthening of the role of local nobility like the Guelph dynasty, which at its height controlled the duchies of Saxony and Bavaria. In terms of manuscript production, the great age of imperial commissions was largely over. Instead, monasteries began to produce deluxe manuscripts for in-house use or for distribution across their networks. The increased patronage of local nobility, as well as the growing prominence of cathedral schools and universities, meant that book culture itself was changing. New texts were being copied, and new ways of illuminating were being explored.

Gospel Book (MS Ludwig II 3)

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

One of the earliest foundations to flourish in the wake of the tumultuous Investiture Controversy was the Benedictine monastery of Helmarshausen in Saxony. Its abbots acquired important relics from Trier, providing the impetus for new building campaigns as well as promoting manuscript production. This Gospel book is an early witness to the monastery’s cultural vitality. Its inventive evangelist portraits combine new styles of painting from the Rhine-Meuse region with local Saxon traditions. The portrait of Luke is rendered in strong outlines, with drapery characterized by nested V-folds and modeling achieved through heavy bands of shading. In contrast to these innovations, the simulated textile designs of the facing page refer directly to the abstract tradition of painting cultivated at nearby Corvey in the tenth century.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Germany, Helmarshausen, ca. 1120–40

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS Ludwig II 3, fols. 83v–84r

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1983

Heiningen Gospels

Although monasteries produced the majority of manuscripts in the twelfth century, the task of illuminating these works did not always fall to monks. For prestigious commissions, monasteries could seek out professional painters, who traveled widely in search of work. This Gospel book was illuminated by two artists. The first was a monk of Hamersleben; the second, whose work is shown here, was a professional painter with a strikingly different style. The figure of the evangelist Matthew has been endowed with a thoughtful expression and dramatic drapery. He appears to occupy three-dimensional space, an effect heightened by contrasts between the varied surfaces. In these respects, the illuminator demonstrates firsthand knowledge of contemporary artistic developments across the continent. The pastiche book box (above), in which the manuscript was stored, combines thirteenth-century elements with nineteenth-century additions, such as the large plaque of Christ at center.

"Heiningen Gospels" (Fragment), in Latin

Germany, Hamersleben, ca. 1170 and ca. 1200 (manuscript)

Germany, Saxony, thirteenth century, and France, Paris, nineteenth century (book box)

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.565, fol. 13v

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1905

Stammheim Missal

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

In the twelfth century, monks at the Benedictine monastery of St. Michael advocated for the canonization of their founder, Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim (d. 1022). These efforts coincided with a flurry of artistic activity, including the production of spectacularly illuminated manuscripts—among them, this missal. By depicting the story of salvation, the prefatory cycle shapes viewers’ understanding of the manuscript’s contents. The radially organized Creation miniature, at left, focuses on the plight of Adam and Eve, who are encircled by representations of the six days of Creation. Their expulsion from paradise and the story of Cain and Abel, below, indicate the sinful state of humankind. The facing miniature, in contrast, represents the promise of salvation. At center, a personification of divine wisdom holds up Christ amid Old Testament figures who prophesize his incarnation.

"Stammheim Missal,” in Latin

Germany, Hildesheim, ca. 1170

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS 64, fols. 10v–11r

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1997

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

Around the middle of the twelfth century, monks at the Benedictine monastery of St. Michael at Hildesheim, in Lower Saxony, were advocating for the canonization of their famed eleventh-century founder—Bishop Bernward, who was a great patron of the arts as well as the tutor of Emperor Otto III. As part of this effort, the monks initiated a flurry of artistic activity that included building renovations and the production of spectacularly illuminated manuscripts such as this mass book, known as the Stammheim Missal. With fifteen full-page paintings and well over a dozen half-page decorative initials, this manuscript is among the most sophisticated and richly illuminated books of its time.

After a splendid calendar, the Stammheim Missal opens with a prefatory cycle of three miniatures depicting Creation, Divine Wisdom, and the Annunciation. The complex compositions of this opening cycle provide the viewer with a theological framework for understanding the contents of the manuscript. The first miniature, at left, focuses on the creation of Eve from Adam’s side. Around them are the six days of Creation. The scenes below depict their expulsion from Paradise and the subsequent story of Cain and Abel, both indicative of the sinful state of humankind.

If the first miniature emphasizes the Fall from Grace, the facing page represents the promise of salvation. At center, a personification of Divine Wisdom holds up a figure of Christ. They are surrounded by Old Testament kings, prophets, and patriarchs. Taken together, these figures present the coming of Christ as the fulfillment of Old Testament prefigurations. On the next page, Christ’s incarnation is depicted with the miniature of the Annunciation.

This approach of presenting events from the Christian New Testament as the fulfillment of prophecies from the Hebrew Bible is known as typology, and it was a central feature of monastic art in the twelfth century.

Leaf from a Gospel Book

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

This leaf once formed part of a magnificent Gospel book, written and illuminated at Helmarshausen, but perhaps made for the monks at Corvey. Originally positioned at the beginning of Matthew’s Gospel, the leaf features a depiction of Christ embedded within the very first word, Liber (book). Through its inscription (verus in utroque deus extat homoque; “truly he exists as both man and god”), Christ’s scroll emphasizes the dual nature of his incarnation, while the very placement of the figure, inhabiting the sacred text, visualizes the link between Christ and the word of God.

Leaf from a Gospel Book, in Latin

Germany, Helmarshausen, ca. 1190

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchased on the J. H. Wade Fund, 1933.445

Psalter (MS W.10)

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

The scriptorium at Helmarshausen regularly exported both manuscripts and artists to nearby Paderborn and Corvey, and even to centers as far as Scandinavia. In the second half of the twelfth century, however, this pattern of patronage changed as local nobility began to commission works directly from the monastic scriptorium. An early example of this trend, this diminutive psalter was likely made for a local Guelph princess—perhaps Gertrud (ca. 1152–1197), the daughter of the duke of Saxony and a future queen of Denmark. Dressed in red brocade lined with ermine, she raises her hands in prayer. The object of her devotion, depicted on a now-lost facing page, was likely the Virgin Mary.

Psalter, in Latin

Germany, Helmarshausen, ca. 1160–70

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.10, fols. 6v–7r

Purchased by Henry Walters, before 1931

Berthold Sacramentary

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

In 1215, fire consumed the monastery at Weingarten. Major relics were lost, and the abbey church had to be rebuilt. In this context of renewal, Abbot Berthold engaged a professional painter—known as the Berthold Master—who illuminated a new set of liturgical books, chief among them this magnificent Mass book. The miniature for the feast day of St. Oswald, at left, depicts the saintly king of Northumbria seated next to Bishop Aidan of Lindisfarne. According to legend, Oswald gave so charitably to the poor that the bishop blessed the king’s generous hand. The hand never aged, becoming a wonder-working relic after his death. Emphasizing the miraculous qualities of Oswald’s relics, this full-page miniature promotes the cult of one of Weingarten’s patron saints. The manuscript preserves its original curtains and treasure binding.

"Berthold Sacramentary," in Latin

Illuminated by the Berthold Master

Germany, Weingarten, ca. 1215–17

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.710, fols. 101v–102r

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1926

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

In the decades around 1200, pilgrims began to arrive at the Abbey of Weingarten, in Swabia, to venerate an extraordinary relic of Christ’s blood, which was donated by Judith of Flanders, the duchess of Bavaria and a great patron of the arts. Coinciding with this rise in pilgrimage, Berthold, the abbot of Weingarten, undertook an ambitious program of cultural production to reinforce the abbey’s new status as a religious center of international renown. Berthold’s leadership was tested when a catastrophic fire destroyed the monastery in 1215. Despite significant losses, the abbot was able to rededicate his church in just a few years. It is in this context of renewal and revitalization that Berthold engaged a professional painter to illuminate a new set of liturgical books for the monastery.

This magnificent mass Book represents Berthold’s most important commission. Shown here is the miniature for the feast of St Oswald, an obscure English saint who was initially not highly esteemed at Weingarten. Nevertheless, his relics formed part of Judith’s donation and Berthold made a conscious effort to raise the saint’s profile after the relics of other saints were destroyed in the fire. The use of colorful embroidered repairs, one of which you see on the margin of the right page, was part of a broader effort to make the manuscript appear older than it actually was. In a similar manner, the manuscript’s magnificent jeweled cover harks back to the age of Carolingian treasure bindings like the Lindau Gospels.

With its spectacular paintings and its range of precious materials from gold and gems to textiles and relics, the Berthold Sacramentary marks a high point of monastic book production. Moreover, as a prestigious memorial object, intimately tied to the abbey’s history and its self-image, the manuscript both celebrated and legitimized the forms of devotion so carefully promoted by Abbot Berthold.

Hainricus Missal

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

After a burst of activity, the Berthold Master vanished from Weingarten without a trace. Just a few years later, a second professional artist took his place and painted miniatures for an important commission from a high-ranking member of the abbey: this Mass book for the sacristan Henry (Hainricus) to use in a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary, which he was responsible for maintaining. Placed unusually at the core of the manuscript just before the Eucharistic prayer, the Coronation of the Virgin, at right, attests to Henry’s devotion to Mary. The surrounding symbols of the four evangelists and four rivers of paradise underscore her central role in the universal Church. The manuscript preserves its original treasure binding, silk curtains, and remarkable thirteen-strand bookmark.

"Hainricus Missal" (Gradual, Sequentiary, and Sacramentary), in Latin

Germany, Weingarten, ca. 1220–30

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.711, fols. 56v–57r

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1926

Leaf from the Wettingen Gradual

RITE AND RITUAL

This monumental leaf from a choir book testifies to the ambition of the monks who commissioned it. With such commissions, newer mendicant orders like the Augustinians sought to place themselves on par with older foundations like the Benedictines. The illuminator responsible for this leaf worked in a manner derived from the latest fashion at the French court. Arranged from bottom to top like a stained-glass window, four scenes fill the initial I. They depict Augustine teaching; the dream of his mother, Monica; his baptism; and, finally, Bishop Augustine instructing monks. The scroll “spoken” by the monk in the lower margin reads, “Pray for us, blessed Father Augustine.”

Leaf from the “Wettingen Gradual,” in Latin

Germany, Cologne, ca. 1330

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchased on the Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund, 1949.203

Homilary

RITE AND RITUAL

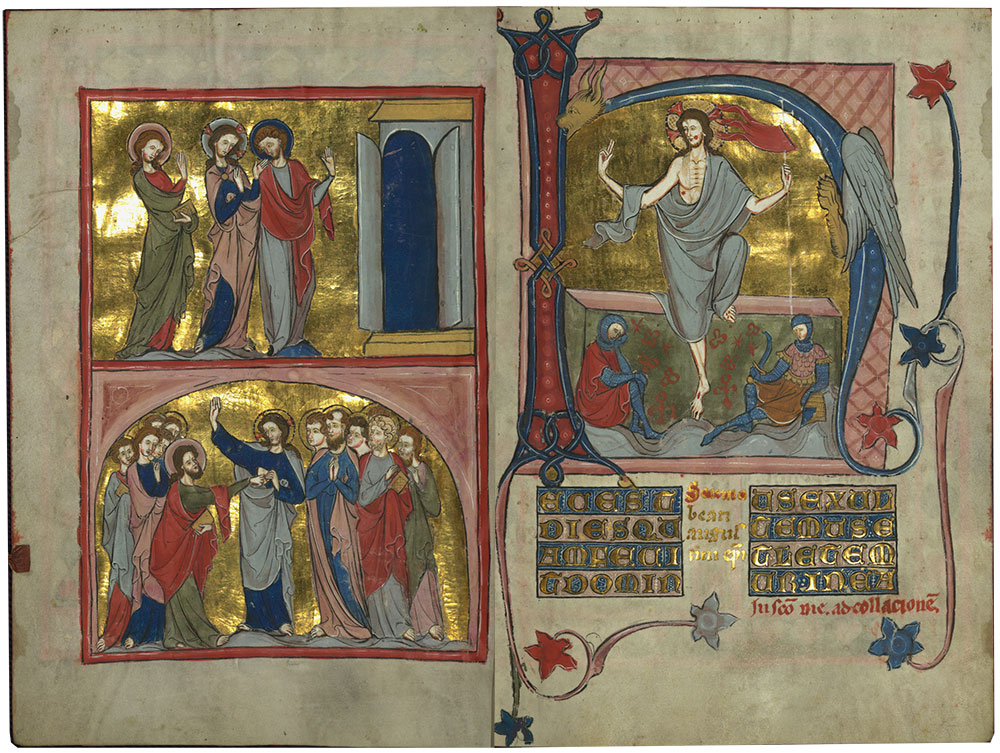

In its profuse use of gold, whether in the burnished backgrounds or the display scripts, this collection of homilies emulates the lavish aesthetic of imperial manuscripts of the early Middle Ages, despite its adoption of Gothic conventions. The homilary—a collection of sermons—was made for and in part by a community of Cistercian nuns. A reform order, the Cistercians traditionally eschewed such luxury, but not here. In its monumentality, the grand initial of the Resurrection rivals that of the full-page miniature on the facing page, which depicts two of Christ’s appearances to the apostles after his Resurrection: Christ as a pilgrim on the road to Emmaus and the Doubting Thomas.

Homilary, in Latin

Germany, Westphalia, ca. 1330

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.148, fols. 45v–46r

Purchased by Henry Walters, before 1931

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

This richly painted book contains a collection of sermons for use during the Easter season. It is part of a pair, of which the other volume—now in Oxford—gathers together sermons for Christmas time.

Both manuscripts were made for a Cistercian convent in Westphalia, a region in northwestern Germany. In the High Middle Ages, the Cistercians were celebrated for their austerity, which led them to reject all forms of luxury, including the visual arts. In this book, however, no trace of such restraint remains.

A team of at least three professional artists painted most of the miniatures. Set against sheets of burnished gold, their elegant, elongated figures reflect the latest developments in painting from France. Shown here, at left, are two scenes that demonstrate Christ’s resurrection: above, is Christ on the Road to Emmaus, where he appears to two apostles who previously thought him dead; below is the Doubting Thomas, who needed physical proof that Christ had risen from the dead, and thus presses his finger into the wound in Christ’s side. At right, filling the oversized initial H, is the Resurrection itself. Two small soldiers are shown sleeping as Christ rises from the tomb. The composition evokes statues of the Resurrection that were a common fixture of Cistercian convents in Westphalia and played an important role in the Easter liturgy, as did this manuscript.

Gold is also used for the display scripts and the massive frames that adorn nearly every page of the manuscript. Several of these text pages were painted by the nuns for whom the manuscript was made. The extravagant use of gold represents just one of a number of archaic features that appear to have been deliberately adopted to evoke the lavish commissions characteristic of imperial female foundations of the earlier Middle Ages.

Leaf from an Apocalypse

RITE AND RITUAL

This large leaf, one of several surviving from a dismembered picture book of the Apocalypse, depicts John the Evangelist as the author of the book of Revelation, surrounded by seven angels representing the seven churches. The tabernacles and pinnacles around the angels evoke the façade of a Gothic cathedral, just as the blue-and-red palette suggests a stainedglass window. While it depicts the kingdom of heaven, the full-page miniature also represents the towering ambition of the high medieval Church. Didactic picture books of this kind had represented a popular genre in German monasticism since the twelfth century.

Leaf from an Apocalypse

Germany, Hessen, ca. 1340–50

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS 108

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011

Leaf from a Missal (MS M.892.2)

RITE AND RITUAL

Set against a gold background, a priest elevates a Eucharistic host within an initial C marking the beginning of the Feast of Corpus Christi. Behind him stand a deacon and a subdeacon holding a paten (plate). As this Mass celebrates the real presence of Christ in the Eucharistic offering, the most prominent detail is the monstrance (receptacle) at the corner of the altar, displaying a consecrated host. Unusually for a Mass book, the bottom margin is filled with animal scenes humorously depicting a world upside down. This missal was painted by Master Bertram, a well-documented artist in Hamburg whose workshop also produced panel paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts.

Leaf from a Missal, in Latin

Illuminated by Master Bertram (ca. 1340–1415) for Johann von Wustorp (d. 1381)

Germany, Hamburg, before 1381

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.892.2

Gift of the Fellows, 1958

Liturgical Set

RITE AND RITUAL

This deluxe liturgical set, likely commissioned by an abbot of St. Trudpert, was created by a lay goldsmith from Freiburg named Master John (Johannes), who ran an active workshop in the thirteenth century. The chalice, paten, and straw (to prevent spilling) were essential vessels used by a priest for the consecration of the Eucharist, the moment in Mass when the offering of bread and wine was ritually transformed into the body and blood of Christ. The rich visual program is typological: Old Testament prophecies at the base of the chalice are paired with New Testament scenes around its node (middle part). The use of typology continues on the paten, where Abel and Melchisedech serve as prefigurations of Christ as both sacrifice and celebrant.

Liturgical Set from the Abbey of St. Trudpert at Münstertal

Germany, Freiburg im Breisgau, ca. 1230–50

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Cloisters Collection, 1947.101.26–28

Lichtenthal Altar Tabernacle

RITE AND RITUAL

This tabernacle was commissioned by Sister Margaret (Greda) Pfrumbon, whose family made several gifts to the Cistercian convent of Lichtenthal in the Rhineland, where she was a nun. Margaret appears alongside St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the famous monastic reformer and a fellow Cistercian. Like the three magi, Margaret offers her gift to the Virgin and Child. With its translucent enamel over an engraved ground, the tabernacle emulates stained-glass windows. The baldachins placed over angels on each corner of the tabernacle resemble those at Reims Cathedral, the coronation site of French kings. The lions serving as feet for the object link the tabernacle to the Temple of Solomon, the archetypal site of the Holy of Holies.

"Lichtenthal Altar Tabernacle"

Germany, Upper Rhine (?), ca. 1330

The Morgan Library & Museum, AZAZ 48

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1908

Speculum virginum (Mirror of Virgins)

MONASTIC LEARNING AND REFORM

The Mirror of Virgins, a book instructing clerics in the spiritual care of nuns, exemplifies the changing status of visual imagery within monastic reform movements. The “mirror” of the title defines the text as a place where readers can examine the “face of their hearts.” A dialogue between a monk (Peregrinus) and a nun (Theodora), the work contains a dozen narrative, allegorical, and diagrammatic images that serve as instruments of pastoral care. The Trees of Vices and Virtues dominate one opening to the near exclusion of text. The text directs “novices and the untutored” toward these “two little trees,” so that “anyone studying to improve himself can clearly see what things will result from them.”

Conrad of Hirsau

(ca. 1070–ca. 1150)

Speculum virginum (Mirror of Virgins), in Latin

Germany, Himmerod, ca. 1200–1225

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.72, fols. 25v–26r

Purchased by Henry Walters, 1903

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

No work better exemplifies the changing status of visual imagery within monastic education than the Mirror of Virgins, a book of spiritual instruction for nuns written between 1130 and 1140. The manuscript’s use of tinted line drawings is characteristic of didactic works of monastic instruction within the context of twelfth-century efforts to reform monasticism by raising educational (and moral) standards. The author of the text, who was most likely from Hirsau, an important center of reform monasticism, refers to the mirror of the book’s title as a place where readers can examine the “face of their hearts.”

This early thirteenth-century copy was created at Himmerod, a monastery founded in 1134 by Bernard of Clairvaux. Despite Bernard’s well-known hostility to images, the monks there quickly came to consider them indispensable in certain contexts such as the pastoral care of nuns.

Constructed as a dialogue between a monk (Peregrinus) and a nun (Theodora), the Mirror includes a dozen narrative, allegorical, and diagrammatic drawings that aid in spiritual guidance and education. The Trees of the Vices and Virtues dominate the opening displayed here to the near exclusion of the main text. Whereas the branches of Vice, on the left, hang downward toward the Whore of Babylon, the Virtues, on the right, rise up from Jerusalem and Humility. Atop the Virtues, Christ stands as the “New Adam,” in contrast to the “Old Adam” whose fall was rooted in pride.

Underscoring the identification of the Tree of Vices with the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden, two serpents coil around the trunk. The text directs “novices and the untutored” toward these “two little trees,” so that “anyone studying to improve themselves can clearly see what things will result from them.”

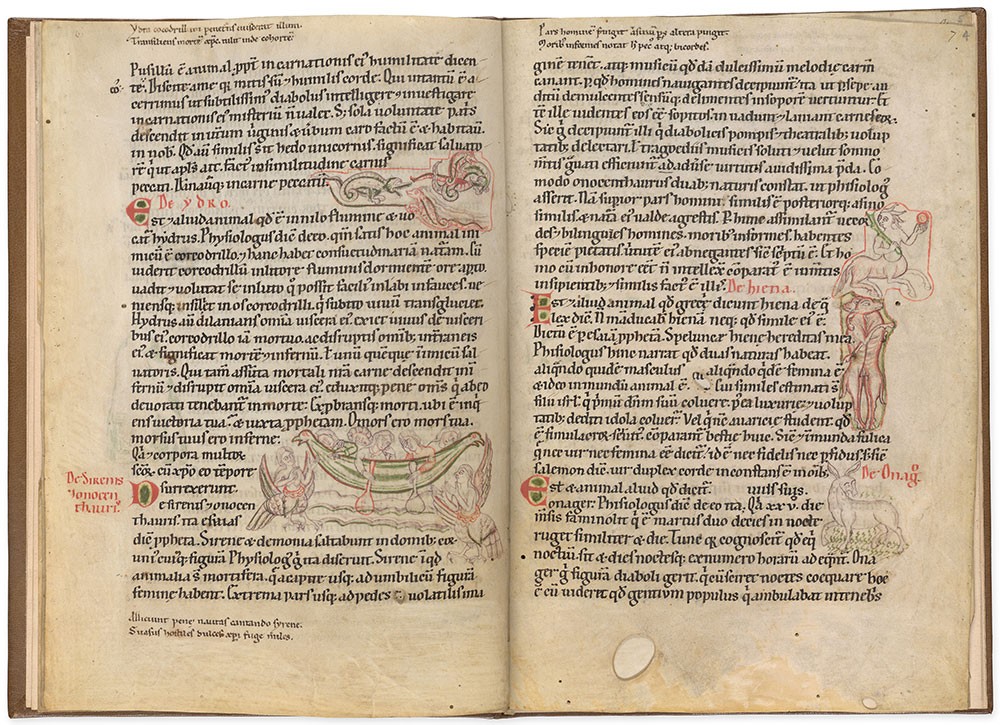

Bestiary

MONASTIC LEARNING AND REFORM

Monastic learning included texts on the natural world. A characteristic example from the important Benedictine monastery at Göttweig, this compilation of animal lore is based on ancient and early medieval sources. Beginning with the lion and ending with the phoenix, the text describes some thirty different animals, both real and imaginary. At upper left is the hydrus, legendary enemy of the crocodile; directly below are sirens, birdlike beasts that prey on sailors. At upper right is the onocentaur, a half-man, half-donkey hybrid; below that are sex-changing hyenas, related to sodomy; and the creature at lower right is a braying onager, symbol of the devil. Added later, rhyming couplets in the margins offer typological and moral interpretations of the animals, of a type also featured in the encyclopedic Concordance of Charity.

Bestiary (Dicta Chrysostomi), in Latin

Austria, Göttweig, ca. 1140–50

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.832, fols. 3v–4r

Gift of the Fellows, 1958

Leaf from a Schoolbook

MONASTIC LEARNING AND REFORM

This delicate drawing exemplifies the educational program of medieval monasticism. Personified liberal arts (branches of learning) descend from a magisterial figure of Philosophy. She is depicted as the queen of heaven, crowned and holding a scepter, flanked by personifications of the sun and moon and surrounded by stars and clouds, as if a celestial vision. Reminiscent of Pentecost imagery, seven streams flow from her breast, nourishing each of the liberal arts. The double-sided drawing marries principle to practice; whereas the arts are personified as women, on the reverse, their practitioners are presented as famous men.

Leaf from a Schoolbook, in Latin

Austria, Salzburg, ca. 1150–60

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.982

Purchased on the Belle da Costa Greene Fund, with special gifts of the Glazier Fund, Dr. Ruth Nanda Anshen, Mrs. Harold M. Landon, and Miss Julia P. Wightman, 1978

Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation)

HISTORIES OF SALVATION

The Mirror of Human Salvation was composed in northern Italy but enjoyed its widest dissemination north of the Alps. Juxtaposing scenes from the New Testament with Old Testament prefigurations, the images offer a lesson in the shape of sacred history and the nature of memory and meditation. In the first image, Mary mourns under the cross, surrounded by events on which she, as a model for the viewer, reflects. Her pose is echoed in the three prefigurations that follow: Anna is perturbed by the absence of her son, as was Mary when she could not find Jesus. The woman from the parable of the lost coin likewise stands for Mary’s loss of her son. Finally, Saul forces his daughter Michal to marry Phalti when David goes into hiding.

Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation), in Latin

Germany, Franconia (Nuremberg?), ca. 1350–1400

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.140, fols. 37v–38r

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1902

Biblia pauperum (Paupers’ Bible)

HISTORIES OF SALVATION

Pointing out the links between the Old and New Testaments constituted a staple of Christian commentary on the Bible. Despite its name (a misnomer), the Paupers’ Bible circulated primarily in Benedictine and Augustinian monasteries in Austria and Bavaria. Configurations varied, but in this unfinished copy, each page features four Old Testament prophets surrounding a New Testament subject, with a pair of Old Testament scenes below. At left, for example, the Crowning with Thorns is paired with the Shaming of Noah and the Mocking of Elijah. At right, Christ Carrying the Cross is related to Abraham and Isaac as well as Elijah’s Encounter with the Widow of Zarephath. Added much later, the inscriptions represent an attempt to finish the manuscript.

Biblia pauperum (Paupers’ Bible), in German

Germany, Regensburg, ca. 1435

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.230, fols. 14v–15r

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1906

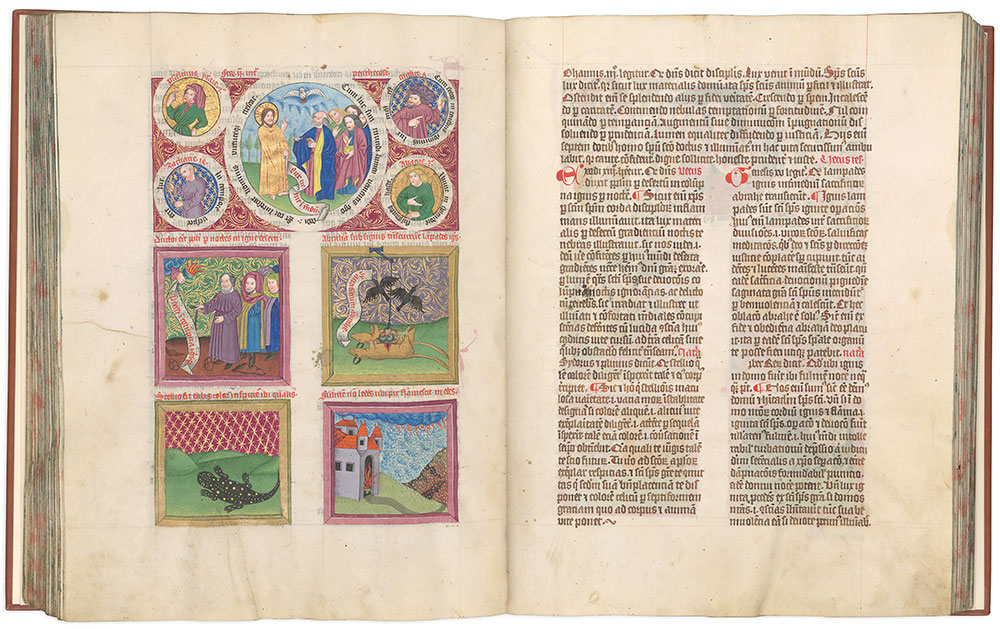

Concordantia caritatis (Concordance of Charity)

HISTORIES OF SALVATION

This compendium systematically links prefigurations from the Old Testament and the natural world to their Christian realizations in the New Testament. At top, for example, the principal scene is Christ telling Nicodemus that light has come into the world. Directly below are two scriptural prefigurations: Moses and the Israelites led by a pillar of fire, and God’s covenant with Abraham. There follow two examples from natural history: a chameleon, and a burning house in a hailstorm. Just as the lizard takes on the color of its surroundings, so an observer can adopt exemplary behavior. Just as hail and lightning cannot harm a blazing house, so the Last Judgment cannot harm one ablaze with the Holy Spirit. This opulent copy was made for Leonhard Dietersdorfer, a cleric and imperial notary from Salzburg.

Ulrich of Lilienfeld

(ca. 1308–1358)

Concordantia caritatis (Concordance of Charity), in Latin and German

Austria, Vienna, ca. 1460

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.1045, fols. 120v–121r

Gift of Clara S. Peck, 1983

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

The Concordance of Charity, written between 1345 and 1351 by Ulrich, abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Lilienfeld in Austria, represents the most ambitious handbook of its kind from the Middle Ages. Typological in character, the work follows the liturgical calendar. Employing types drawn from nature as well as Scripture, it incorporates a moralized bestiary into an exposition of salvation. With 248 groups of images totaling over 1,000 illustrations, it is no wonder that this opulently decorated copy commissioned by Leonhard Dietersdorfer—a cleric and notary of Salzburg as well as a master of theology—was never completed.

At the top of the page exhibited here, four prophets surround the principal subject: Christ telling Nicodemus that light has come into the world a scene selected for the Monday after Pentecost.

The lower part of the page presents four types: Moses and the Israelites led by a pillar of fire and God’s covenant with Abraham. Having been asked to sacrifice a heifer, a goat, a ram, a dove, and a pigeon, Abraham cuts them all but the fowl in half. Birds of prey descend and are driven away. Then, after sunset, “there arose a dark mist, and there appeared a smoking furnace and a lamp of fire.” The artist condenses all this into a single miniature in which the furnace and lamp hang from a hook projecting from the upper frame. Connecting both images to Pentecost is the common theme of fire descending from the heavens.

Lower still are two types drawn from natural history: on the left a chameleon; on the right, a burning house in a hailstorm. Just as the lizard takes on the color of its surroundings, so too an observer adopts the exemplary behavior of someone he sees. And just as hail and lightening do not endanger a house that is already ablaze, so the Last Judgment cannot endanger someone whose heart is already ablaze with the fire of the Holy Spirit.

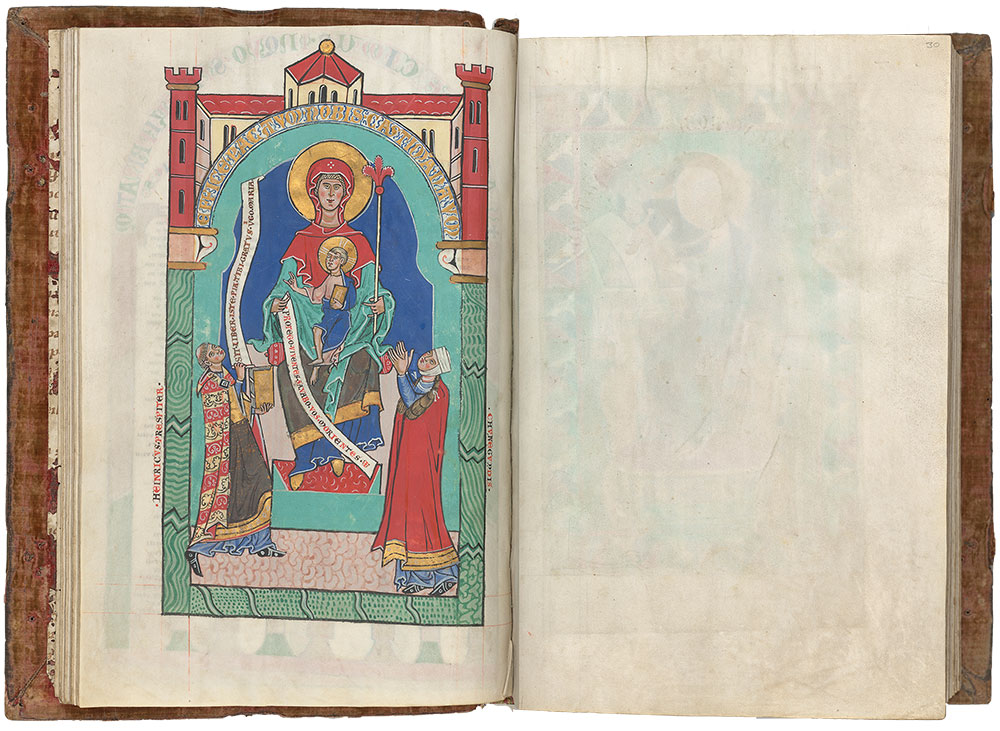

Seitenstetten Gospels

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

Established in 1112 by a local count, Udalschalk von Stille, and his brother-in-law, Reginbert, the monastery at Seitenstetten actively commemorated its founding dynasty for well over a century. When Abbot Henry (r. 1247–50) commissioned a deluxe Gospel book for the monastery, his aristocratic patrons were featured prominently in its decorative program, as was Henry himself. In the dedication miniature shown here, Henry (Heinricus) and a noblewoman offer their book to an enthroned Virgin and Child. Henry is identified as a priest, suggesting that this commission may slightly predate his rule as abbot. The woman is identified as Cunigunde (Chunegundis), who is attested in contemporary sources as the widow of Otaker von Stille and thus a member of the dynasty.

"Seitenstetten Gospels," in Latin

Austria, Seitenstetten (?), ca. 1247

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.808, fol. 29v

Purchased, 1940

Seitenstetten Missal

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

In 1254, the monastery at Seitenstetten burned to the ground. Circumstances were so dire that the archbishop of Salzburg intervened, granting indulgences, or the forgiveness of sins, for anyone offering financial support to the monks. As the well-connected son of the duke of Silesia, Archbishop Ladislaus (ca. 1237–1270) came to Salzburg via Padua, where he had studied at the renowned university. He likely played a role in the commissioning of this missal, coinciding with the rededication of the monastery. Of the manuscript’s three local artists, the one responsible for this diptych of the Virgin and Child with a facing Crucifixion demonstrates firsthand knowledge of contemporary Paduan painting, which must have been facilitated by the archbishop’s connections. The donor at the foot of the Virgin is likely the abbot of Seitenstetten.

"Seitenstetten Missal" (Gradual, Sequentiary, Sacramentary), in Latin

Austria, Salzburg, ca. 1265

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.855, fols. 110v–111r

Purchased from Mrs. Edith Beatty, 1951

Leaf from the Arenberg Psalter

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

Arranged in a double-tiered format, this leaf from a deluxe psalter depicts the Flagellation of Christ and the Crucifixion set against a solid gold background. The unusual frame heightens the drama of the narrative. Grammatical clues in the manuscript’s Latin prayers indicate that it was created for a woman, perhaps as a gift for the wedding of Helen, the daughter of Duke Otto of Brunswick, to Hermann II of Thuringia. This book marks the emergence of a new style of painting known as Zackenstil (Zigzag style), derived in part from Byzantine and Venetian art, and characterized by thick, jagged folds of drapery that defy gravity. This new style spread quickly throughout the empire, becoming a standard mode of figural representation across all artistic media.

Leaf from the “Arenberg Psalter,” in Latin

Germany, Hildesheim, ca. 1239

Art Institute of Chicago

Purchased on the S. A. Sprague Fund, 1924.671

Psalter (MS Ludwig VIII 2)

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

Würzburg was the site of an active workshop of professional illuminators around the middle of the thirteenth century. Working for monasteries and nobility, Christians and Jews, these lay painters were familiar with slightly earlier, aristocratic works like the “Arenberg Psalter.” Although the intended recipient of this deluxe book of Psalms remains unknown, it counts among the earliest and most lavish products of the workshop. Featuring the opening words of Psalm 1 spread across two pages, the double frontispiece begins with a large letter B at left, in which Christ sits enthroned above a seated King David, who is flanked by musicians. Unusually, the facing page presents the remaining letters in a golden grid, enhancing the sacred text.

Psalter, in Latin

Germany, Würzburg, ca. 1240–50

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS Ludwig VIII 2, fols. 11v–12r

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1983

Prayer Book (MS M.739)

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

This prayer book, which conceivably belonged to St. Hedwig, features a vast prefatory cycle of approximately 160 Old and New Testament scenes, framed by inscriptions in German. These narrative scenes are depicted in unusually elaborate detail. The story of Susannah and the Elders, for example, begins at upper left with the heroine physically accosted by two older men, then falsely accused of adultery before a judge. Below, a young Daniel intercedes on her behalf, interrogating the elders. Finally, as punishment for their false witness, the men are stoned to death. The story of Daniel continues on the facing page. This elaborate tale of virtue in the face of corruption may have had special appeal to the book’s first, female owner.

Prayer Book (Cursus sanctae Mariae virginis), in Latin and German

Germany, Bamberg (?), ca. 1204–19

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.739, fols. 18v–19r

Purchased, 1928

Hedwig Codex

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

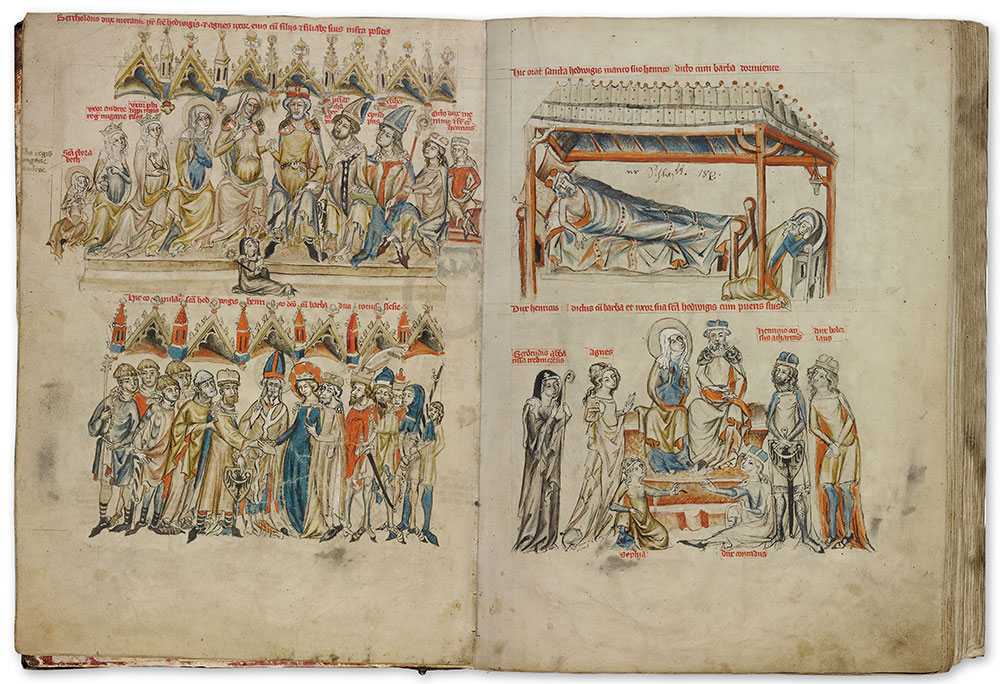

In 1203, Duke Henry I of Silesia (d. 1238), from the Piast dynasty, and his wife, Hedwig of Andechs (d. 1243), founded the Cistercian convent of Trebnitz (Trzebnica). Hedwig would retire there as a widow. For centuries thereafter, all the convent’s abbesses were princesses of the Piast dynasty. This manuscript reproduces the dossier in support of Hedwig’s canonization, which occurred in 1267. Depicting episodes from her life and tracing her family history, its drawings provide emblematic images of aristocratic piety and of female piety in particular. At left is the family of Hedwig’s father, Berthold IV of Andechs, and, below, the union of Hedwig and Henry I, who, following the birth of their children, had a chaste marriage. The first scene on the facing page depicts Hedwig praying while her husband sleeps. The scene below depicts the couple with their children.

"Hedwig Codex," in Latin

Written by Nicolaus of Prussia for Duke Ludwig I of Liegnitz and Brieg

Poland (Silesia), 1353

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MSMS Ludwig XI 7, fols. 10v–11r

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1983

Der wälsche Gast (The Italian Guest)

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

Written around 1215–16, The Italian Guest is the sole surviving poem by Thomasin von Zerclaere, a canon at the court of the German-speaking patriarch of Aquileia in Friuli (northern Italy). The work seeks to educate noblemen in the rules and norms of courtly love, chivalry, ethics, rulership, and good manners. The illustrations constitute a critical part of the work’s didactic program and enhanced its appeal to lay readers. At left, personifications of vices rob a nobleman of his clothing. At right, Justice, Nobility, and Courtliness join hands in a circle; a second miniature shows the winners and loser of backgammon, a critique of gambling. This copy was commissioned by Kuno von Falkenstein (1320–1388), archbishop elector of the imperial city of Trier.

Thomasin von Zerclaere

Der wälsche Gast (The Italian Guest), in German

Germany, Trier, ca. 1380

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS G.54, fols. 24v–25r

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

Aristocratic patronage made its mark on secular illustration, as exemplified by The Italian Guest, a didactic poem written around 1215–16. The sole surviving work of Thomasin von Zerclaere a canon at the court of the German-speaking patriarch of Aquileia in Friuli at the northern end of the Adriatic Sea, it seeks to educate noblemen in the rules and norms of courtly love, chivalry, ethics, rulership, and what we would call good manners. The poem reflects the perceived need to lend the court, which by the thirteenth century had emerged as a cultural center independent of ecclesiastical control, its own ethical rationale. The illustrations, which comprise as many as 125 separate subjects, constitute a critical part of the work’s didactic program and certainly enhanced its appeal to lay readers. This fourteenth-century copy of the work made for Kuno von Falkenstein, the archbishop-elector of the Free Imperial City of Trier, speaks to its crossover appeal to both clerical and aristocratic audiences.

The three miniatures on this opening, indebted in style to contemporary French illumination, focus on the Virtues and Vices. Rather than prefacing sections of the text, the images have been inserted directly into the relevant passages of the narrative, enhancing their immediacy.

The first, on the verso, shows a nobleman robbed of his clothing by personifications of the vices, literally stripping him of his nobility. Kneeling below the unfortunate noble is a personification of Wickedness; to the right stand two women exemplifying Deceit and Inconstancy.

Two miniatures on the facing page represent, respectively, the affinity among Justice, Nobility, and Courtliness—expressed by means of their joining hands in a circle—and, in a scene reminiscent of later genre paintings, the winners and loser of a board game, in this case backgammon, a critique of gambling. Whereas the loser has lost even his clothes and bewails his blindness, his opponents exclaim, “See how he cries out!” Harking back to famous literary heroes, Thomasin asks: “Where are Erec and Gawain, where are Parzival and Iwein? . . . The virtuous people are all hidden away.”

Weltchronik (World Chronicle)

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

The 243 illustrations in this copy of Henry of Munich’s World Chronicle entertained and edified aristocratic readers. As part of the work’s expansive paraphrase of Jewish scripture in German verse, one miniature shows King David battling the Philistines; the other shows David playing his harp and followed by trumpeters, leading the ark of the covenant back to Jerusalem. When the oxen hauling the ark stumbled, Uzzah, the son of Abinadab, sought to steady it with his hand, in violation of the law, and was immediately struck down, as seen at the center. The oblong formats spanning both text columns lend the images narrative thrust. While depicting distant historical events, the lively miniatures would have evoked contemporary military customs and courtly pageantry for the manuscript’s readers.

Henry of Munich

Weltchronik (World Chronicle), in German

Germany, Regensburg, ca. 1360

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.769, fols. 181v–182r

Purchased, 1931