Imperial Networks

9th–11th Century

The Carolingian and Ottonian dynasties, named after Charlemagne (ca. 748–814) and Otto I (912–973), respectively, laid the groundwork for the Holy Roman Empire. Their rulers deliberately sought out the imperial title to legitimize their control over diverse kingdoms and principalities that, at the empire’s height, encompassed much of present-day western and central Europe. The manuscripts produced during their rule engaged with the legacy of ancient Rome and embodied the ambitions of the patrons for whom they were made. Scribes and artists in this period developed prestigious visual and graphic elements for their books, including the use of gold ink, purple parchment, a hierarchy of scripts, elaborate decorative initials, and spectacular treasure bindings. Paying attention as much to visual qualities as to content, the Carolingians and Ottonians fundamentally shaped the role of illuminated manuscripts in the Middle Ages. The most deluxe works were often commissioned as gifts and thus played a crucial role across carefully cultivated networks of power. These manuscripts featured prominently in solemn rituals at the heart of both religious life and governance. As preservers of institutional memory, the illuminated manuscripts of this period vividly articulate notions of empire, authority, and tradition.

Lindau Gospels

BOOK AS TREASURE

This treasure binding is a composite made of two distinct covers brought together on a Gospel book written and illuminated toward the end of the tenure of Hartmut, abbot of St. Gall, likely for ceremonial use in the abbey church. The jeweled front cover must have been a royal gift of immense importance. It is one of only three surviving examples of metalwork that can be attributed to the court workshop of Emperor Charles the Bald (823–877), who, like his grandfather Charlemagne, was a great patron of illuminated manuscripts. The back cover may have once belonged to a Gospel book commissioned by Charlemagne’s rival Tassilo III (ca. 741–796), Duke of Bavaria. Also, the rare Byzantine and Syrian silks lining the inside covers were likely gifts. Because Carolingians lacked the technology to produce silk, such textiles were highly coveted luxury items, often distributed through royal networks.

"Lindau Gospels," in Latin

Switzerland, St. Gall, ca. 880 (manuscript)

Eastern France, ca. 870 (front cover)

Austria, Salzburg region, ca. 780–800 (back cover)

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.1

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1901

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

This magnificent gospel book was written and illuminated in the late ninth century, at the monastery of St. Gall, which is strategically located along one of the alpine passes leading to Italy. The spectacular front and back covers of the manuscript were made elsewhere and predate the book itself.

The golden front cover is a masterpiece of Carolingian metalwork. The figure of Christ on the cross dominates the center of the composition, around which ten figures are arranged in dramatic poses of grief. Directly above Christ, personifications of the sun and moon mourn his death, as do the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist beneath the cross.

The back cover is no less remarkable. Created for a now-lost luxury gospel book, the cover was made in or around Salzburg about a hundred years earlier than the manuscript it now adorns. Its design consists of a large cross with flared arms, set inside a rectangular enamel frame. Certain details lend the cover a cosmological dimension. The Greek letters alpha and omega are inscribed on the vertical arm of the cross and refer to the beginning and end of time. Likewise, the mass of snakes and other creatures filling the four carved plaques between the arms of the cross establish a link between the Gospels and the primordial act of creation.

Both covers likely reached St. Gall as royal gifts of immense importance. A similar route can be surmised for the rare silk textiles lining the inside of both covers. Because the Carolingians lacked the technology to produce silk for themselves, such textiles were highly coveted luxury items, and were often distributed through royal networks.

Gospel Lectionary

BOOK AS TREASURE

This treasure binding, original to its manuscript, consists of a silver-filigree frame, a silver-gilt cross (noticeably more golden in color), and four ivory plaques of the evangelists (Mark, lower left, is a modern replacement). At its center, the cross features a polished rock crystal protecting an image of the Crucifixion drawn on gold foil. A splinter of the True Cross rests upon Christ’s chest. The surrounding inscription, “The death of Christ was the death of death, and your bite, O Hell,” emphasizes the paradox of Christ’s death as a triumph of eternal life. Through this deliberate staging, the relic appears as the source of the cross’s life-giving power, which emanates from the center in the form of the cover’s abundant vegetal motifs. The book was created at Regensburg, likely for the Benedictine abbey of Mondsee (near Salzburg), where it was preserved for much of the Middle Ages.

Gospel Lectionary, in Latin

Germany, Regensburg, ca. 1030–50, with later additions

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.8

Purchased by Henry Walters, before 1931

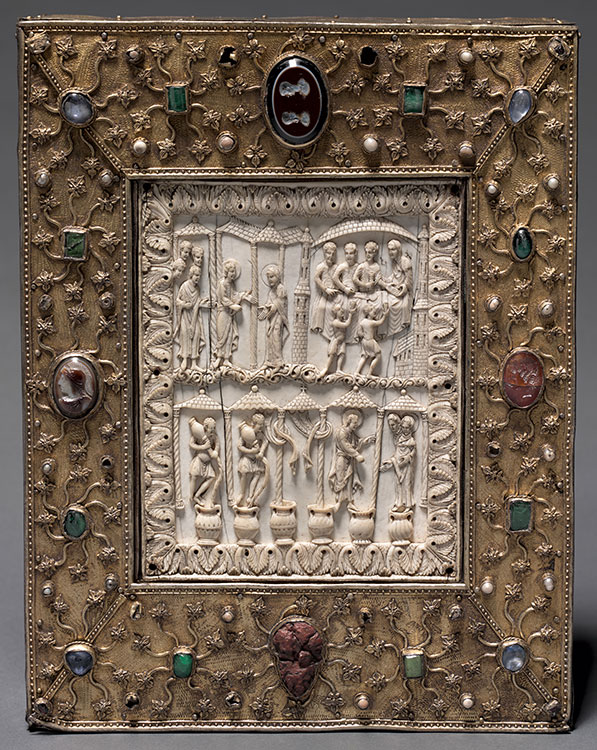

Book-Shaped Reliquary

BOOK AS TREASURE

Modeled after a treasure binding, this reliquary was commissioned by Duke Otto the Mild (1292–1344) as part of his magnificent memorial donation to the collegiate church (now cathedral) of St. Blaise in Brunswick. The engraved effigies of that church’s three patron saints on the reverse tie the object to the dynastic foundation. The front cover reuses much older objects, including an eleventh-century ivory of Christ’s miracle at the Wedding at Cana, as well as ancient cameos—small carved glass or gemstone plaques—interspersed with precious gems. The use of such spolia (spoils) forms part of a broader representational program that proclaimed the status and authority of the patron’s family while adding to the prestige of their local church. Among the relics within were pages from the four Gospels, lending the object a quasi-liturgical function.

Book-Shaped Reliquary

Germany, Lower Saxony, ca. 1340 (reliquary)

Belgium, Liège (?), late eleventh century (ivory)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Gift of the John Huntington Art and Polytechnic Trust, 1930.741

Saint-Remi Gospels

CAROLINGIAN PRECEDENTS

Among the largest cities in Roman Gaul, Reims was also a center of artistic renewal in the Carolingian empire. This efflorescence was fostered by enterprising archbishops like Hincmar of Reims (806–882), who renovated several important monasteries in his domain, including Saint-Remi just outside the city walls. Preserving the relics of St. Remigius, who baptized King Clovis and converted the Franks to Christianity, the monastery laid claim to a fundamental moment in Frankish history. Commissioned by Hincmar for Saint-Remi’s rededication, this manuscript was written exclusively in gold ink. The portrait of the evangelist Matthew is deeply classicizing, a reference to the city’s ancient past. Featuring the opening words of the Gospel, the purple ground of the facing page likewise refers to imperial traditions.

"Saint-Remi Gospels," in Latin

France, Reims, ca. 852

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.728, fols. 14v–15r

Purchased, 1927

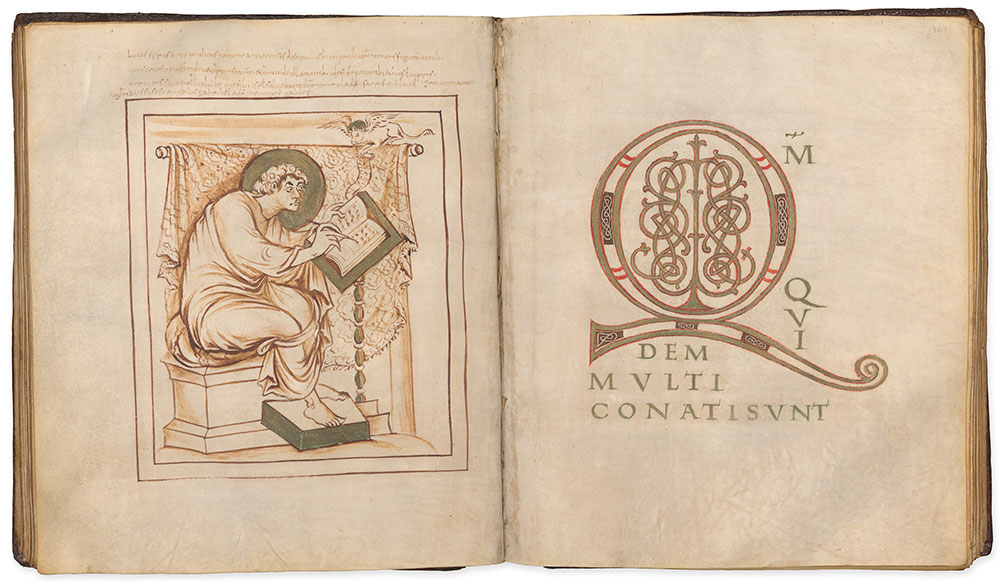

Gospel Book (MS M.640)

CAROLINGIAN PRECEDENTS

Books played a crucial role in establishing networks of power. Over twenty Carolingian manuscripts name Hincmar of Reims as donor, and many more are associated with his patronage. Most were created for use in and around Reims, but their influence was widespread. This Gospel book features two evangelist portraits and the beginnings of a third, all drawn in a distinctly Reimsian style. While to a certain extent unfinished, the heavy use of shading—as evident in this image of the evangelist Luke—suggests that the portraits were never intended to be painted. The artist may have been trained at Reims, but the manuscript itself was produced at an unknown regional scriptorium. The use of brass instead of gold further suggests that the manuscript was not produced at a major center.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Northeastern France or Belgium (Liège?), late ninth century

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.640, fols. 100v–101r

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1919

Gospel Book (MS M.860)

CAROLINGIAN PRECEDENTS

Inviting to his court the best scholars throughout Europe, Emperor Charlemagne (ca. 748–814) attempted to reform and standardize writing itself, which varied widely across the empire. Scribes working at important monastic centers like St. Martin at Tours developed new styles of script modeled on those of the ancient Romans. In this manuscript from Tours, the title page (at left) announces the beginning of Matthew’s Gospel. Written on bands of imperial purple, the golden capitals recall stone-carved inscriptions of ancient Rome. At right, Matthew’s Gospel begins with Liber generationis (Book of the generation of Jesus Christ). Here, the scribe combines Roman letterforms with nonclassical interlace ornaments, transforming sacred words into a work of art.

Gospel Book, in Latin

France, Tours, ca. 857–62

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.860, fols. 14v–15r

Purchased with the Assistance of the Fellows, 1952

Epistle Lectionary

CAROLINGIAN PRECEDENTS

Strategically located along one of the alpine passes leading to Italy, the abbey of St. Gall was favored by Carolingian rulers, who demonstrated their support through a series of privileges, allowing the monks to govern themselves independently from the local bishop. Abbot Hartmut (r. 872–83) actively fostered its cultural life, commissioning a great number of books to be written “for the communal use of the monastery.” Among them was this lectionary, illuminated in a characteristic nonfigural style. The alternating gold and silver of the manuscript’s opening initials echoes the alternating gold and silver lines of text. While these opening pages are the most prominently decorated, the manuscript contains nearly 150 decorative initials, each of which introduces a reading for Sundays and special feast days.

Epistle Lectionary, in Latin

Switzerland, St. Gall, ca. 880

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.91, fols. 1v–2r

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1905

Astor Lectionary

OTTONIAN BEGINNINGS

Looking back to Carolingian models (on view at the entrance to the exhibition), illuminators at Corvey developed a new style of painting that was largely abstract, using ornamental forms inspired by silks, gems, enamels, sumptuous metalwork, and imperial monograms. These manuscripts demonstrated not only the wealth and munificence of the imperial family but also the international status of their power. This Gospel lectionary features ornamental pages that preface the readings for important Masses. For Christmas, thirteen words stretch across nine pages of designs culminating in the word Mattheum (Matthew), at left, depicted in a monogrammatic composition. At right, the same approach is used to form the words In illo tempore (In that time). As the personal signs of rulers, monograms were potent symbols of authority in the Middle Ages and possessed a nearly magical quality.

"Astor Lectionary," in Latin

Germany, Corvey, ca. 950

New York Public Library, MA 1, pp. 14–15

Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

Quedlinburg Gospels

OTTONIAN BEGINNINGS

This Gospel book was likely made for the imperial convent of Quedlinburg, among the most important foundations in Saxony. Established in 936 by Otto I and his mother, Mathilda, the abbey served as a memorial site for the Ottonian family. Its abbesses were Ottonian princesses, many of whom were actively engaged in politics. Befitting such prestige, this manuscript is one of the largest and most splendidly illuminated products of the Corvey scriptorium. Luke’s Gospel begins with an elaborate interlace initial Q framed by monochrome textile designs in the corners. The text continues in gold on the facing page, set against a striking textile background in shades of purple. The evocation of luxury objects like silk cloth relates to Otto’s extensive diplomatic activities, which resulted in the exchange of precious goods from centers spanning from Córdoba to Constantinople.

"Quedlinburg Gospels," in Latin

Germany, Corvey, ca. 950–70

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.755, fols. 99v–100r

Purchased, 1929

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

Beginning around the middle of the tenth century, Otto the Great, or members of his family, began commissioning a number of deluxe manuscripts from the scriptorium at Corvey—an important monastery in Saxony. Little is known about the exact circumstances of their production, but both the script and illumination of these manuscripts suggest close ties with the imperial family. Based on their early histories of ownership, these manuscripts were likely produced for export as imperial gifts.

This gospel book is among the largest and most splendidly illuminated products of Corvey in the tenth century. It was likely made for the convent of Quedlinburg, which served as a mausoleum for the imperial family. Each of the four gospels in this book begins with a sumptuous four-part sequence of ornamental text pages. Shown here is the opening for the Gospel of Luke, the first word of which (quoniam) is formed by an elaborate initial Q framed by monochromatic textile designs in the four corners. The sacred text continues in gold on the facing page, which likewise features a striking textile design for the background. These pages exemplify the new style of painting developed by illuminators at Corvey—a style that was largely abstract and inspired by precious luxury objects like silk textiles, gems, enamels, and metalwork.

Ornate in the extreme, these manuscripts were meant to do more than just dazzle their viewers. The particular approach to painting developed at Corvey demonstrated not only the wealth and munificence of the imperial family, but also the international status of their power.

Gospel Book (Fragment)

OTTONIAN BEGINNINGS

These fragmentary leaves once formed part of a Gospel book given to Reims Cathedral. Otto I’s younger brother Bruno (925–965) was not only duke of Lotharingia and archbishop of Cologne, but also regent of France during this period. He had a particularly strong interest in Reims and perhaps played a role in the donation of this manuscript. The title page for Luke’s Gospel, at left, demonstrates how painters could simulate precious materials. Four fictive enamel medallions occupy most of the page. Filling the spaces between the medallions, the golden text takes on the form of a cross. The facing page features a large initial Q framed by a fictive enamel border, seemingly lined with pearls. The unusually painted vegetal motifs in the corners of each page evoke carved gems (intaglios).

Gospel Book (Fragment), in Latin

Germany, Corvey, ca. 950–70

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.751, fols. 1v–2r

Purchased, 1952

Gospel Book (MS M.651)

OTTONIAN PATRONAGE

Marking a break from local painting traditions in Cologne, this Gospel book demonstrates the influence of artistic developments at the island monastery of Reichenau, an important center of Ottonian patronage. The portrait of Matthew features an expansive gold background, faintly articulated with golden vegetal motifs at bottom and nearly imperceptible golden stars above. Matthew’s symbol, a winged man, emerges from the architecture to offer him a scroll. The facing page combines Reichenau traits—the curved L, for example, and the anchoring of the initial to the frame—with elements more local to Cologne, such as the portrait medallions, inspired by ancient coinage. Although the patron of this manuscript is unknown, its illumination points to the high standing of Cologne, whose bishops were often active as chancellors at court.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Germany, Cologne, ca. 1030

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.651, fols. 8v–9r

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1920

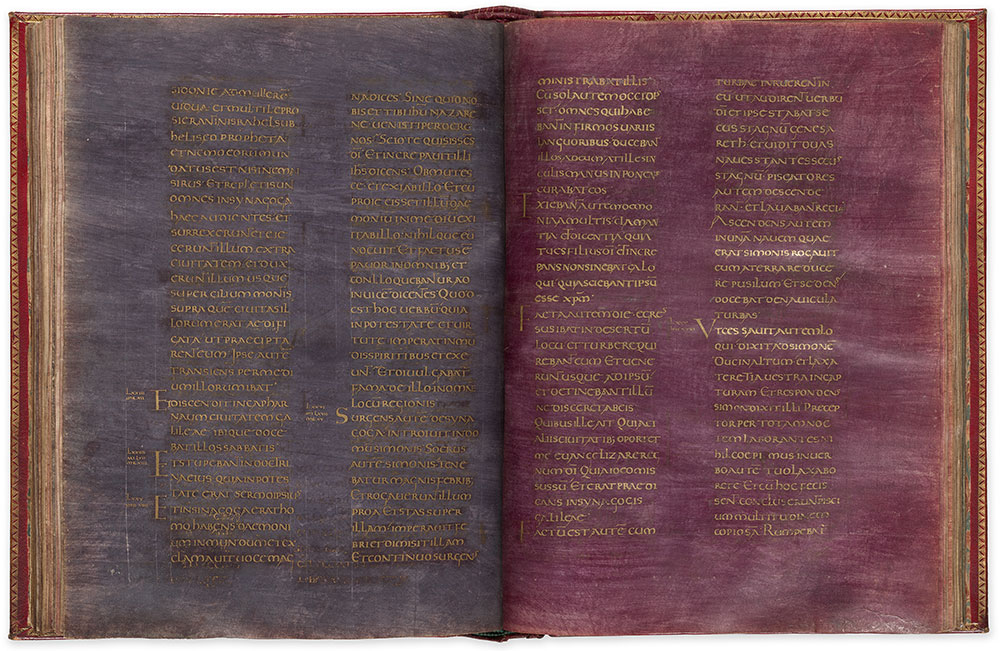

Golden Gospels

OTTONIAN PATRONAGE

This Gospel book was written entirely in gold ink on purple-painted parchment. It evokes the venerable tradition of ancient manuscripts represented by the fragmentary leaf from a sixth-century Gospel book displayed above.

The “Golden Gospels” contains only the sacred text, written in double columns using an uncial (uppercase) script long out of fashion by the tenth century. With as many as sixteen scribes copying the text, the finished leaves were stacked together before the gold ink was completely dry, leaving visible offsets. The plant-based purple pigment varies in hue to such an extent that several batches must have been made, without regard for consistency. The manuscript was likely created in haste, perhaps as an imperial gift to mark a particular occasion for which there was little time to prepare. The intended recipient is unknown, but in the sixteenth century it was owned by King Henry VIII of England.

"Golden Gospels," in Latin

Germany, Trier, ca. 980

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.23, fols. 72v–73r

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1900

Leaf from a Gospel Book (“Codex Petropolitanus”), in Greek

Syria, Antioch (?), sixth century

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.874

Purchased, 1955

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

This grandiose gospel book is the last in a long line of deluxe manuscripts written entirely in gold or silver ink on parchment that has been stained purple, a color traditionally reserved for emperors and their family. This ancient tradition dates back to the time of the earliest Christian emperors like Constantine the Great, who ruled in the early fourth century. However, by the time this manuscript was made, in the late tenth century, the tradition of the purple codex had largely come to an end. The patron of this manuscript, who may have been Archbishop Egbert of Trier, a former chancellor of Emperor Otto II, likely intended to recreate the appearance of an ancient purple manuscript.

This gospel book was almost certainly made as a gift, and its production involved an enormous team of skilled artisans, including as many as sixteen scribes. They worked in great haste, often stacking together the freshly written pages before the gold ink was completely dry, which explains the offsets visible at the bottom of the left page. The fact that this book was later owned by King Henry VIII of England suggests that it may have been created as a gift from the Ottonian emperors to an English dignitary.

A brief painted inscription runs along the outer fore-edge of the manuscript, stating that “the inside of the book is more ornate than the outside.” This inscription refers in a typically medieval way to a now-lost treasure binding that once adorned the manuscript. The inscription juxtaposes the conspicuous material value of the now-lost jeweled covers with the much greater spiritual value of the book’s text.

Gospel Book (MS W.7)

OTTONIAN PATRONAGE

The island monastery of Reichenau was among the most celebrated centers of artistic production during the Ottonian period. Nearly sixty deluxe manuscripts from its scriptorium survive. The vast majority of these commissions were created for export, and the very consistency and longevity of this output attests to a well-organized workshop with a rich supply of models. Belonging to the end of this tradition, this Gospel book opens with a remarkable dedication miniature featuring an unidentified abbot handing the manuscript to St. Peter. As gatekeeper of heaven, Peter holds open a door leading to an altar on which the same book is blessed by the hand of God. By the mid-eleventh century, Reichenau had begun to lose its preferred status as other artistic centers vied for imperial favor.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Germany, Reichenau, ca. 1050

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.7, fols. 9v–10r

Purchased by Henry Walters, ca. 1913–1931

St. Peter’s Gospels

SALZBURG AND THE ART OF REFORM

Around the year 1000, the abbey of St. Peter’s in Salzburg was reformed with the goal of instituting a more disciplined form of monastic life, which found expression in the reinvigorated production of manuscripts like this Gospel book. Sumptuously illuminated by two artists, it was likely used on special feast days. The miniatures respond to artistic developments at centers of monastic reform like Regensburg, Reichenau, and Fulda. The main inspiration, however, was a Gospel book commissioned by Emperor Henry II (973–1024), himself an active reformer, for his new foundation at Bamberg (where it remains today). Against a gold ground, John the Evangelist looks to an eagle, his symbol, which holds open a book. At right, the opening words of his Gospel appear in gold on purple ground (In principio erat verbum; “In the beginning was the word”). Many of the miniatures retain their original protective silk curtains.

"St. Peter’s Gospels,” in Latin

Austria, Salzburg, ca. 1020

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.781, fols. 188v–189r

Purchased on the Lewis Cass Ledyard Fund, 1933

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

Monasteries with imperial patronage enjoyed a relative independence from local oversight. With few exceptions their abbots answered only to the emperor or the pope—a freedom that enabled them to amass considerable wealth and to pursue ambitious programs of artistic production. For most of the tenth century, however, this was not the case in Salzburg—the seat of the Archbishop of Bavaria. Traditionally, the archbishop was simultaneously the abbot of the most important monastery in the region, St. Peter’s. This situation changed dramatically in 987, in response to monastic reform movements that swept throughout the empire, with a goal of instituting a more disciplined adherence to monastic life, free from unnecessary interference.

A monk from Regensburg, named Tito, became the first independent abbot of St Peter’s. He initiated a series of structural changes resulting in the separation of the abbey from the cathedral and its archbishop.

Known as the St. Peter’s Gospels, this manuscript was one of the first major products of the newly reinvigorated scriptorium at St Peter’s and was produced in the final years of Tito’s abbacy. It was likely used on special feast days at the abbey church. Painted by a main artist and an assistant, its miniatures reflect the most recent artistic developments at important reform centers like Regensburg and Reichenau. The artist’s most important model, however, was a book commissioned by Emperor Henry II for his newly founded cathedral at Bamberg--a choice that speaks to the aspirations of the abbey at Salzburg. Shown here is the opening of the Gospel of John, whose portrait, on the left, is set against a solid gold ground. At right are the first words of the Gospel, set against an extravagantly ornamented purple ground.

Gospel Lectionary

SALZBURG AND THE ART OF REFORM

Generations of painters at Salzburg looked to the “St. Peter’s Gospels” as a source of inspiration. As these foundational miniatures were copied over the decades, a shift toward Byzantine and Italian styles of painting can be observed. The illuminator of this Gospel lectionary took many of his compositions directly from earlier Salzburg manuscripts, but opted for simpler drapery, less modeling, stronger outlines, and a different technique for creating skin tones. The manuscript opens at left with a dedication scene in which an unidentified abbot hands his book to an unidentifiable saint. The miniature at right depicts the Presentation and Betrothal of Mary in the Temple. Crowned by an angel, the young Virgin is presented by her mother, Anna, to her future husband, Joseph. The nude figures atop the two columns are based on the Spinario, an ancient bronze statue from Rome that was famous throughout the Middle Ages.

Gospel Lectionary, in Latin

Austria, Salzburg, ca. 1030–40

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS G.44, fols. 1v–2r

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

Berthold Lectionary

SALZBURG AND THE ART OF REFORM

Berthold, the custodian (custos) of St. Peter’s Abbey, identifies himself as the patron and perhaps even the maker of this manuscript in a decorative inscription at the end of the book (at right): “To the key-bearer of heaven [St. Peter] the custodian Berthold, who made this book, offers it with a joyful heart to pay for all his sins. May he who steals it suffer violent bodily pains.” The unusually graphic curse may have been added in response to the politically backed plundering of local monasteries that was occurring at the time. Berthold’s miniatures feature a dramatically flattened style, with monumental figures, starkly rendered outlines, and narrative elements reduced to only the essentials. Each of these developments can be seen in this miniature of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple.

"Berthold Lectionary," in Latin

Austria, Salzburg, ca. 1080

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.780, fols. 20v–21r

Purchased on the Lewis Cass Ledyard Fund, 1933

Leaf from a Gospel Lectionary

SALZBURG AND THE ART OF REFORM

This leaf once formed part of a Gospel lectionary from Constantinople, written and illuminated around the same time the “St. Peter’s Gospels” was being produced at Salzburg. Pausing after writing the first line of his text, the evangelist Mark is deep in thought. The artist avoids any hint of an architectural setting, allowing viewers to focus instead on the dramatic intensity of the evangelist’s facial expression. The noticeable shift in style at Salzburg may perhaps be attributed to increased trade connections with Venice and northern Italy in the eleventh century, which provided an important link to Byzantium.

Leaf from a Gospel Lectionary, in Greek

Constantinople, early eleventh century

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.530a

Purchased by Henry Walters, before 1931