Another Tradition: Drawings by Black Artists from the American South

In the last three decades, exhibitions and publications have established the rightful place of figures such as Thornton Dial (1928–2016) and the quilters of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, in the canon of twentieth-century American art. The focus has often been on the impressive works of assemblage—whether of found objects or fabric—that have emerged from the Southern United States. Artists only one or two generations removed from slavery, and subjected to the abuses of Jim Crow, developed ingenious formal techniques using found materials and skills learned outside the classroom and studio. Many, like Dial, Nellie Mae Rowe (1900–1982), and Lonnie Holley (b. 1950), exhibited their creations at their homes in elaborate “yard shows,” drawing the attention of passersby and art-world figures alike.

The focus of this exhibition is the medium of drawing. At its core is a group of eleven works acquired by the Morgan in 2018 from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, an organization dedicated to supporting Black Southern artists and their communities. Like assemblage, drawing is an art of “making do.” Its accessibility and directness have always appealed to both artists and their audiences. While some works in the gallery were produced on traditional artist’s papers, others incorporate the unique qualities of found supports. The range of mediums includes watercolor, ballpoint pen, crayon, and even glitter. But the impact of these works ultimately transcends their innovative means. Although each of the eight artists represented speaks with a distinctive voice, the intimate space of the gallery illuminates formal and thematic connections that arise from their shared geographies and experiences.

Another Tradition: Drawings by Black Artists from the American South is made possible by Katharine J. Rayner.

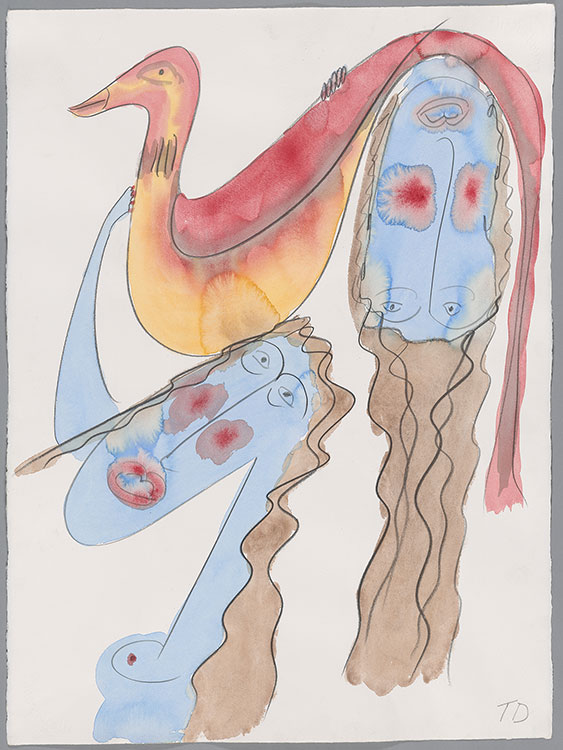

Thornton Dial, Ladies Stand by the Tiger, 1991. Watercolor on paper. Gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund. Photography by Janny Chiu, 2021. © 2021 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Overview

Gallery Images

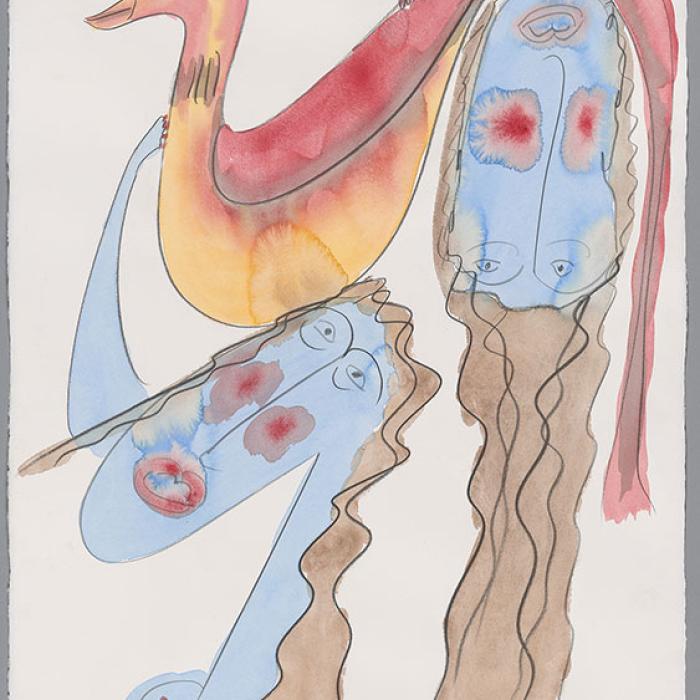

Thornton Dial

Dial became known in the 1980s for his ambitious assemblages. In 1990, he began to create works on paper, quickly establishing a set of motifs that he returned to again and again. One of his recurring themes is the relationship between men and women. He adopted the tiger as an alter ego and allegory for the Black male experience. In this drawing, the tiger is flanked by two female figures and its tail is coiled around a third. Artist Juan Logan writes that “Dial’s tiger is always in charge, as sure as Dial himself, as an artist, is always in charge.” This was in contrast to the precarious conditions African Americans faced in the South.

Thornton Dial

American, 1928–2016

Ladies Stand by the Tiger, 1991

Watercolor, graphite, and fabricated black chalk

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund; 2018.98

© 2021 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Thornton Dial

Thornton Dial

American, 1928–2016

Posing Movie Stars Holding the Freedom

Bird,M 1991

Watercolor and graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund; 2018.97

© 2021 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Thornton Dial

When Dial took up drawing in 1990, he experimented with different materials and papers. In this work—created on a heavy, handmade paper—a bird’s nest rests atop a woman’s head. With exposed breasts and rouged cheeks, and surrounded by lush green plants, she is a symbol of fertility and life force. The work’s title, Life Go On, is a statement of resilience but also one of faith. Dial believed that human creativity illuminates divine creation. He said, “I don’t care what fall, what stand up, life still going to go on. You going to find out how to use the things created in the world for man. The Lord laid out that kind of example for man to go by.”

Thornton Dial

American, 1928–2016

Life Go On, 1990

Watercolor, acrylic, and graphite on handmade paper

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund; 2018.96

© 2021 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Thornton Dial

Thornton Dial

American, 1928–2016

Posing, 1996

Charcoal, graphite, pastel, and watercolor

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund; 2018.99

© 2021 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

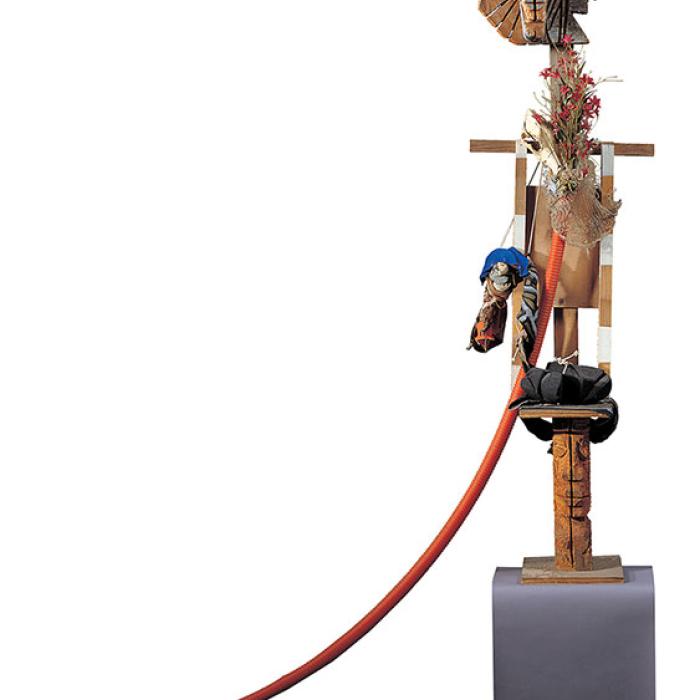

Lonnie Holley

This assemblage, which is constructed from found objects and Holley’s wood carvings, addresses the relationship between the living and the dead. In addition to memento mori such as a skull and flowers, Holley incorporated familiar elements of hoodoo, a syncretic African American belief system. Bundles reminiscent of “mojos,” or charm bags, are suspended from the throne, which symbolizes the spirit of the deceased. Merging past with present, the “crack” of the title refers to the structural crack Holley made in the throne’s narrow foundation as well as to the epidemic of crack cocaine. Holley’s art, like his materials, is rooted in the past. He once said, “If we lose respect for that from which we came, we are . . . On the journey to losing our grip with reality. And art allows us to keep that grip.”

Lonnie Holley

American, b. 1950

The Ancestor Throne Not Strong Enough for No Rock nor No Crack, 1993

Paint on wood with plastic tubing, artificial flowers, fabric, cord, animal skull bone, net, and string

American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of Luise Ross, 2000.10.1

© 2021 Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

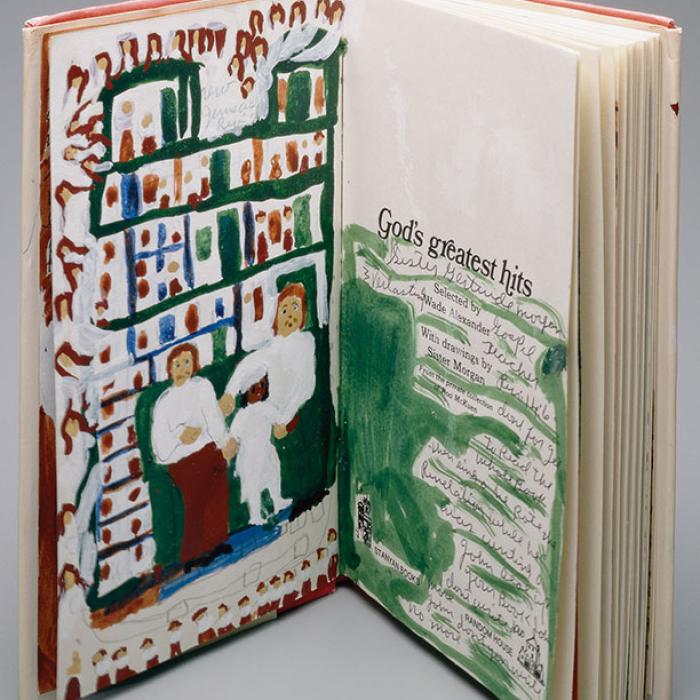

Sister Gertrude Morgan

In 1970, poet Rod McKuen published a diminutive book of Bible quotations accompanied by the drawings of Sister Gertrude Morgan. Morgan had established her Everlasting Gospel Mission in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans several years earlier and had since earned the admiration of figures like McKuen, who collected her work. Morgan adorned the frontispiece of this volume with a drawing of the prophesied New Jerusalem from the book of Revelation, which she depicted as a multistory structure surrounded by angels. In the foreground is the artist herself as the bride of Christ, together with Jesus and a third figure, perhaps the “John” to whom Revelation is attributed. In her lengthy inscription to the right, she borrows a line from a folk song, writing, “Seal up your book John . . .don’t you write no more.”

Sister Gertrude Morgan

American, 1900–1980

God’s Greatest Hits, ca. 1970–74

Tempera, ballpoint pen, and graphite

In God’s Greatest Hits (Los Angeles: Stanyan Books; New York: Random House, 1970)

American Folk Art Museum, New York, Blanchard-Hill Collection, gift of M. Anne Hill and Edward V. Blanchard, Jr., 1998.10.32

American Folk Art Museum / Art Resource, NY

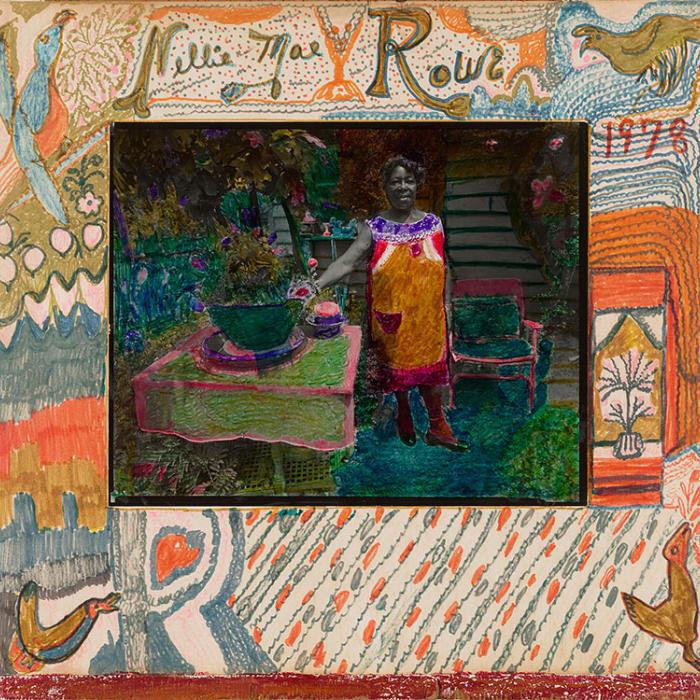

Nellie Mae Rowe

In this self-portrait, Rowe used colorful inks to transform a black-and-white photograph into an otherworldly image in which she resembles a paper doll. The setting of the photo is her home in Vinings, Georgia, which she fashioned into what she called her playhouse.” Visitors to Rowe’s decorated yard encountered a cobbled pathway of bottle caps, homemade dolls, topiary, and Christmas ornaments hung from trees in an idiosyncratic adaptation of the African bottle tree tradition. “I would take nothing and make something out of it,” Rowe often said.

Nellie Mae Rowe

American, 1900–1982

Untitled, 1978

Marker on black-and-white photograph mounted on paper, mounted on plywood, with additions of white paint and oil pastel

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund, 2018.100

© 2021 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Nellie Mae Rowe

Rowe’s drawings teem with animals, recalling her rural upbringing on a farm in Fayetteville, Georgia. In this sheet, two human figures hover in a dreamlike space alongside some twenty animals, including birds, dogs, and snakes. Rowe’s use of the paper reserve creates a feeling of openness, even porousness, amid the density of her marks, which extend from edge to edge of the sheet. This almost gestational space is indeterminate, enhancing the sense that the figures are all interconnected.

Nellie Mae Rowe

American, 1900–1982

Untitled (Woman Talking to Animals), 1981

Ballpoint pen, marker, wax crayon, oil pastel, and graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund; 2018.101

© 2021 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Nellie Mae Rowe

Rowe’s use of a wallpaper sample book for her sketches exemplifies the improvisatory nature of her artistic practice. This image, perhaps showing Christ’s Resurrection, emphasizes the important role of faith in Rowe’s life. Several of the artists in this exhibition considered their art to be an expression of divine will. “God gave me a special talent,” Rowe often said.

Nellie Mae Rowe

American, 1900–1982

Untitled (Textures by Sunworthy), 1976

Crayon in wallpaper sample book

American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of Chuck and Jan Rosenak, 1980.3.17

© 2021 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

American Folk Art Museum / Art Resource, NY

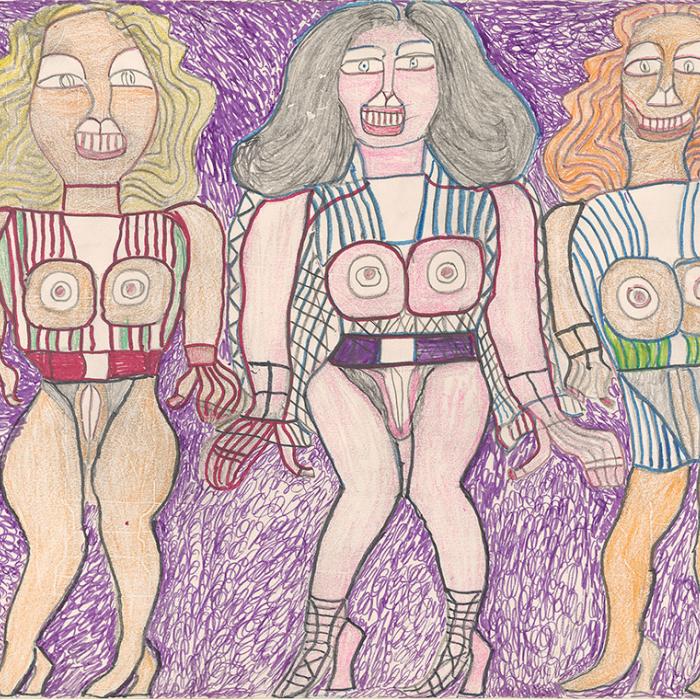

Henry Speller

Speller was an artist as well as an accomplished musician. His drawings reflect a predilection for theme and variation in both his subject matter and his use of pattern, line, and color. Here, he depicts three smiling female figures with varying skin tones, their breasts and genitals exposed. Art historian Lowery Stokes Sims has written, in reference to the sexualized imagery of artist Robert Colescott (1925–2009), “The white female has been displayed and fleshed out in the media, tantalizing, provocative, and yet for the most part has remained socially out of the reach of the black male. It is easy to see how her attainment has been perceived as a way to grasp at power.”

Henry Speller

American, 1903–1997

Glorie Jean and Her Friends, 1987

Marker, wax crayon, and graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund; 2018.103

Henry Speller

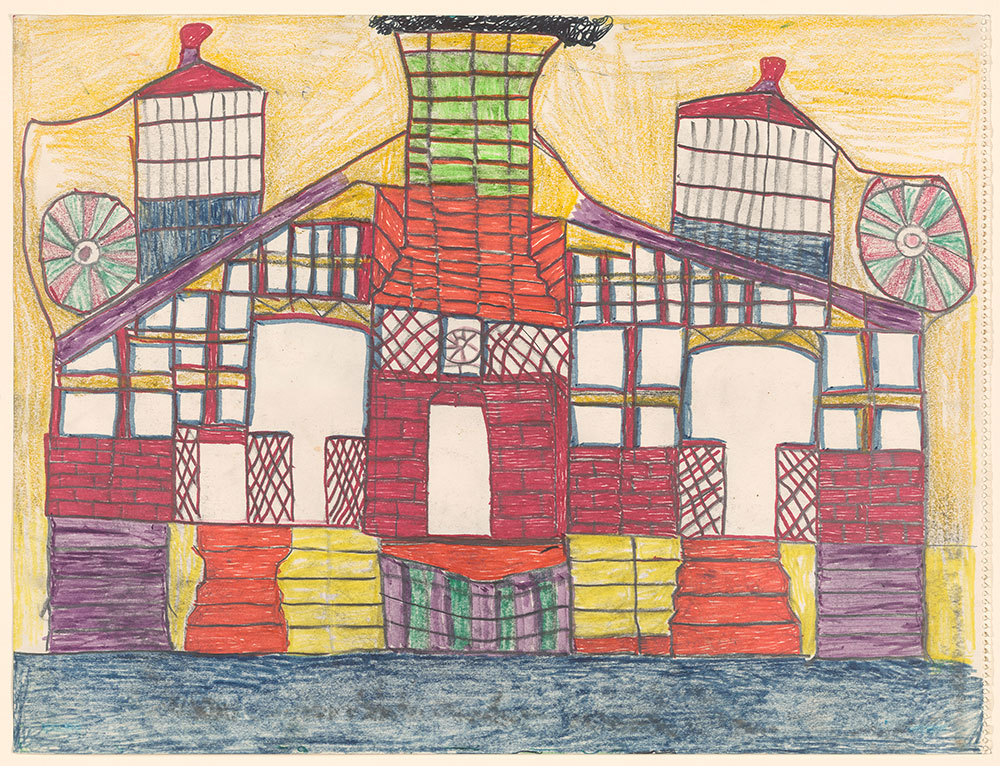

Henry Speller

American, 1903–1997

Courthouse, 1986

Wax crayon, marker, and graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund; 2018.102

Luster Willis

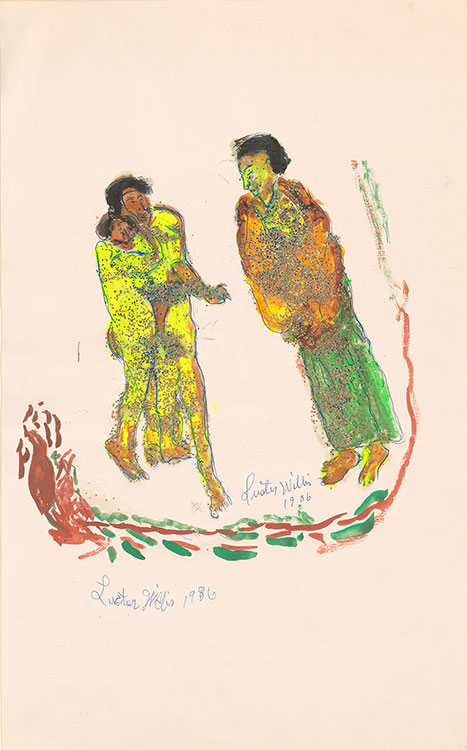

Willis, who often used unconventional materials, drew the three figures here with ballpoint pen and embellished them with bright hues of orange, yellow, and green and sprays of glitter. This scene of an encounter between a nude, huddled couple and a dressed figure holding an infant is based on a 1903 painting by Picasso, La vie (Life). Willis’s interest in Picasso may have been piqued when he served in the army in France during World War II. Standing Together is as ambiguous as Picasso’s somber painting, which was made during a particularly dark time in the Spanish artist’s life, but Willis’s title suggests a more optimistic message.

Luster Willis

American, 1913–1990

Standing Together, 1986

Tempera, glitter, glue, blue ballpoint pen, and graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund, 2018.105r

© 2021 Estate of Luster Willis / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

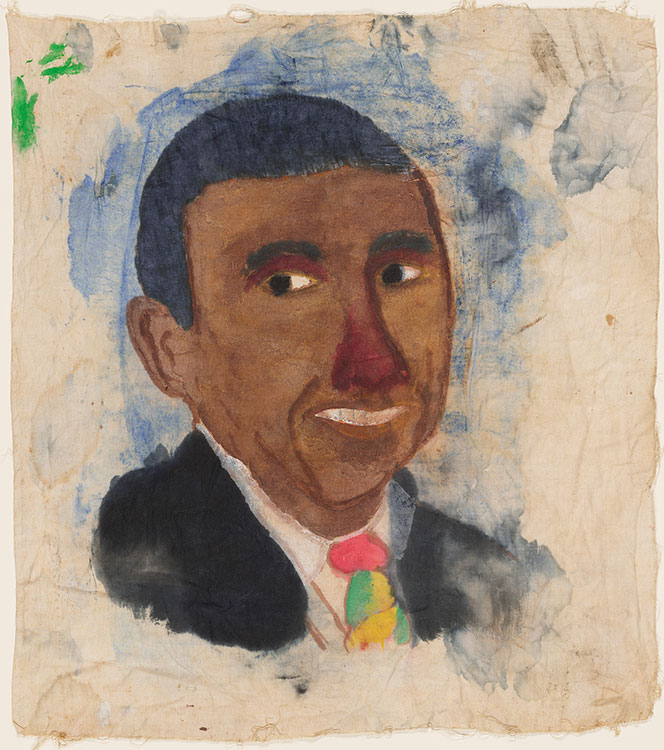

Luster Willis

Luster Willis

American, 1913–1990

Untitled, 1950s

Water-based paint on fabric

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund, 2018.104

© 2021 Estate of Luster Willis / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

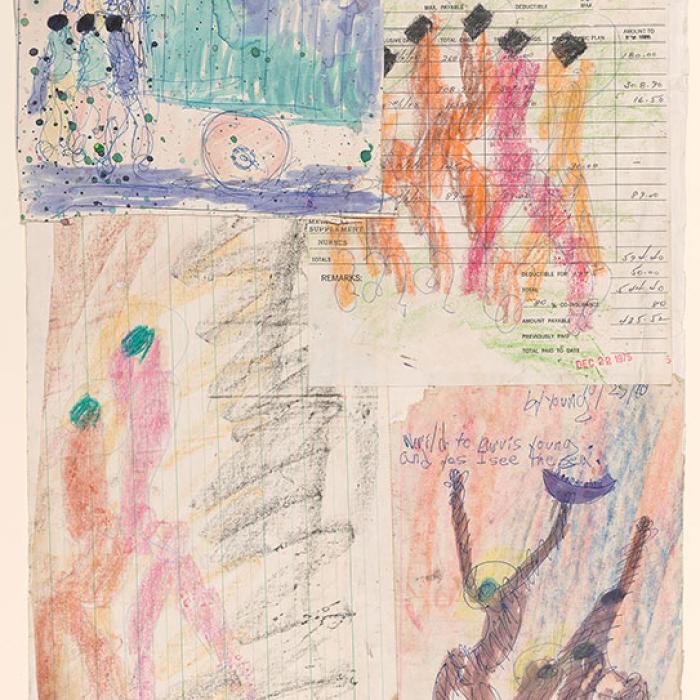

Purvis Young

This double-sided collage is made up of drawings on eight sheets of found paper, four on each side. Young became known in the early 1970s for a monumental work of art that he created in an alley in his hometown of Overtown, Miami. Comprising hundreds of paintings on panel, it established Young’s practice as one of accretion, a strategy that can be seen in the overlapping sheets here. The approach allowed Young to unify scenes as disparate as the one at upper left, depicting young men jumping onto the back of a truck, and the one at lower right, which shows nude, haloed figures in the sea. One of the bathers reaches both arms toward the sky and holds in his hand a boat—perhaps a slave ship—filled with people.

Purvis Young

American, 1943–2010

Untitled, 1980s

Ink, watercolor, and crayon on collage of printed papers

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Daniel Aubry; 2017.389

© Larry T. Clemons / Gallery 721 / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

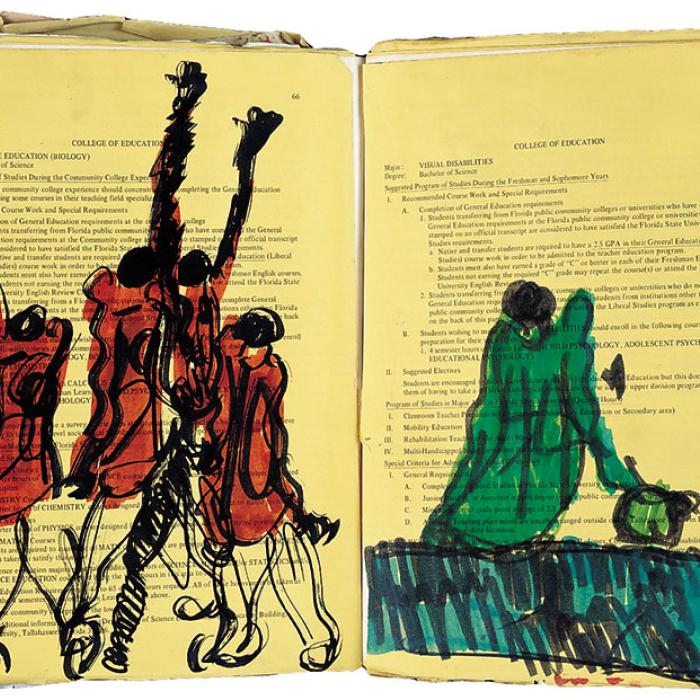

Purvis Young

Inspired by old masters such as El Greco, Young painted elongated, expressionistic figures in dynamic groups. He created his paintings and drawings on a variety of found supports, including panel, paper, and—as in this example—books. Sometimes I Get Emotion from the Game is filled with drawings of men playing basketball and football. As the book’s title and imagery suggest, Young viewed sports as a space of freedom and release from the oppressive conditions that governed the lives of the Black men he knew.

Purvis Young

American, 1943–2010

Sometimes I Get Emotion from the Game, 1980s

Ballpoint pen and marker on paper glued to found book

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection and purchase on the Manley Family Fund; 2018.106

© Larry T. Clemons / Gallery 721 / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York