Women of the Court

Female book owners were a significant presence at Versailles, the French royal residence and seat of government during the reigns of Louis XIV, XV, and XVI. About one-third of the books in the Wrightsman collection bear the coats of arms of women, including queens, empresses, duchesses, and countesses.

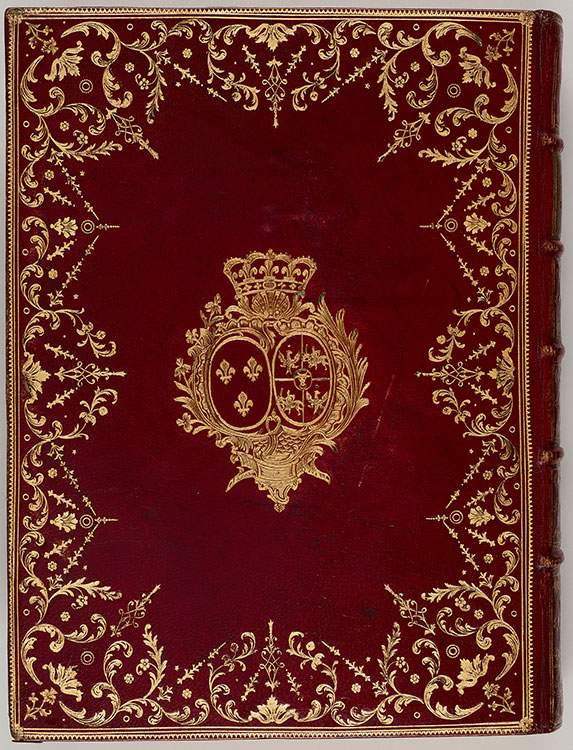

A wife’s family armorial was traditionally paired with that of her husband, with his on the left and hers on the right. While his arms could stand alone, hers typically did not. The exceptions shown here, such as the armorials of Madame de Pompadour, Louis XV’s mistress and a prominent arts patron, and the Mesdames, three daughters of Louis XV, are rare examples of the independent status of certain women at court.

The books on display represent a variety of decorative styles and techniques, from the simple to the lavish, with armorials produced from either a single tool (or plaque) or built up from many small tool impressions. The books with more elaborate bindings were appropriate for display, while those with plainer covers—but decorated spines—were likely destined for bookcases. With the Wrightsman gift, nearly every royal woman at the French court in the eighteenth century is now represented by a signed document or bound book in the Morgan’s collection.

A Prayer Book for Élisabeth de France (1764–1794)

The small prayer book at the center of this case was used by Louis XVI’s younger sister Élisabeth in 1793, when the royal family was jailed in the Temple fortress prior to their executions by the republican government. It is signed inside “Elisabeth, La Temple, 1793,” with a small sketch of the Crucifixion. The text itself is dedicated to Marie Leszczyńska, and the book likely passed from her to her granddaughter Élisabeth. The elaborate binding is in keeping with the traditional degree of decoration on religious books. One large stamp produced the floral vase while many small tools, including several in the shape of butterflies and insects, were used for the surround.

Perhaps Pierre-Paul Dubuisson (act. 1746–62), binder

Dark red morocco, with gilt dentelle and vase-of-flowers motif, on: Heures nouvelles, 1759

Bequest of Julia P. Wightman, 1995; PML 125711

Madame de Maintenon and Françoise-Marie de Bourbon

Before she became Louis XIV’s second wife, Madame de Maintenon was the governess to his illegitimate children, including Françoise-Marie de Bourbon. At left is a

prayer book dedicated to the devout Maintenon. Although the text looks handwritten, it was in fact printed from engraved plates in a style meant to imitate

longhand. The decoration in Françoise-Marie’s manuscript prayer book at right emulates that in her governess’s book. When Françoise-Marie married her cousin

Philippe II, duc d’Orléans—who was regent of France during Louis XV’s minority—she briefly became the highest-ranking woman at court.

Written and bound for Françoise-Marie de Bourbon (1677–1749)

Phillipe Charles Gallonde (1710–1787)

Prières à Sainte Geneviève, 1743

Manuscript on paper

MA 23396

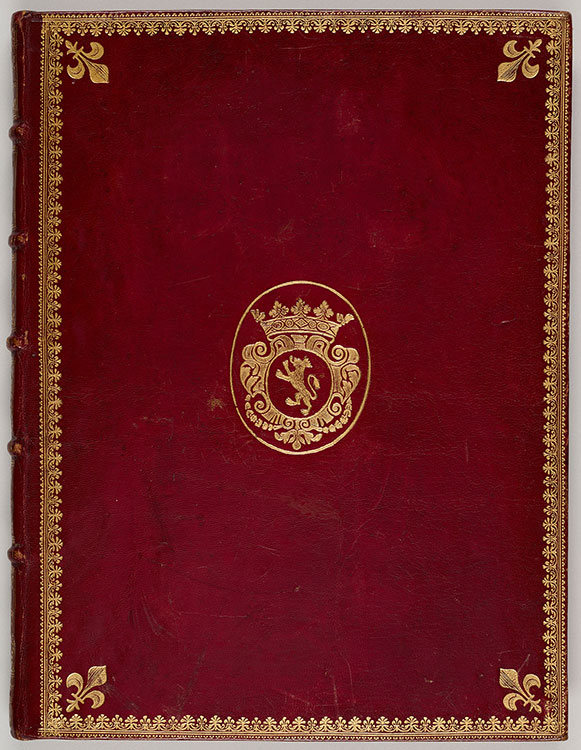

Marie-Adélaïde and Marie Leszczyńska

The two bindings at left in this case belonged to Marie-Adélaïde de Savoie and Marie Leszczyńska, respectively the mother and wife of Louis XV. Marie-Adélaïde’s

entire armorial composition (everything inside the oval) was produced from one large stamp, an unusual choice for the period that suggests there was a need to

efficiently decorate a large quantity of books. In contrast, the armorial and full cover composition for Marie Leszczyńska were built up from small individual

tools, which would have been laborious both to design and to implement—befitting her status as queen.

Bound for Queen Marie Leszczyńska (1703–1768)

Red morocco, with gilt dentelle and armorial, on: Jean Jacques Le Franc de Pompignan (1709–1784)

Poésies sacrées et philosophiques, tirées des livres saints, 1763

PML 198437

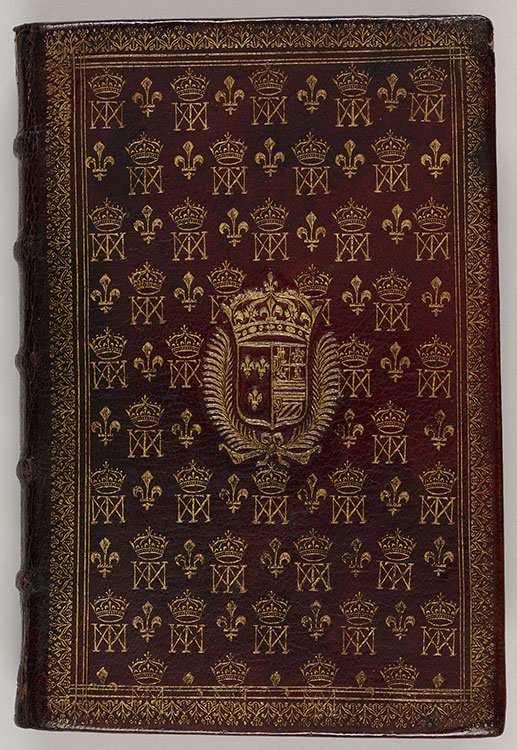

The Queen, The Wife, and the Mistress

The binding at left for Marie-Thérèse, the first wife of Louis XIV, features a grid (semis) of fleurs-de-lis and her crowned MT cypher. Toward the end of the seventeenth century, binding decoration changed to focus on framing patterns with a centerpiece or armorial, as seen in the middle binding for Louis’s second wife, Madame de Maintenon. As an untitled queen of France, she was not permitted to use the French insignia as Marie-Thérèse did; however, this allowed Maintenon’s armorial to stand alone, undefined by that of her husband. Similarly, Louis’s mistress Madame de Montespan could not use the French royal emblems, and her binding at right includes only her initials.

:

Bound for Queen Marie-Thérèse (1638–1683)

Red morocco, with semis gilt tooling and armorial, on: Office de la semaine sainte, 1659

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan by 1906; PML 1884

Bound for Françoise d’Aubigné, marquise de Maintenon (1635–1719)

Augustin Du Seuil (1673–1746), binder

Red morocco, with gilt armorial, on: Guillaume Dardenne (act. 1737)

Description du plan en relief de l’Abbaye de la Trappe, 1708; PML 198439

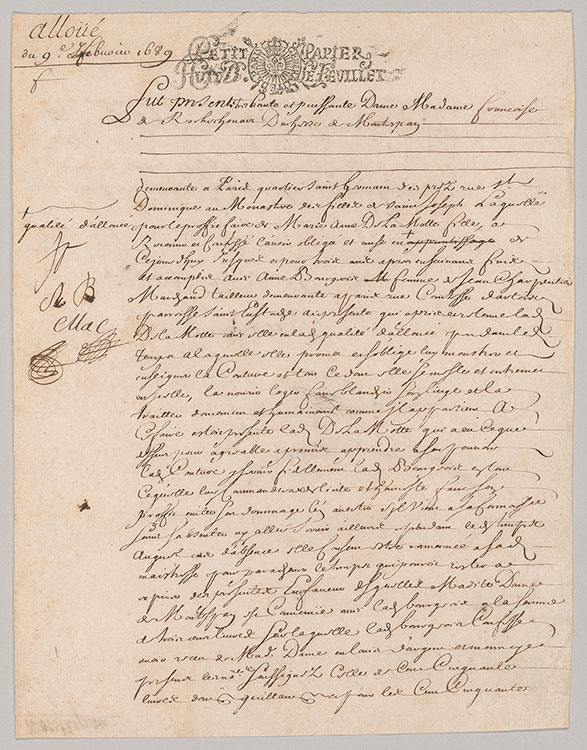

Montespan and Maintenon

Prior to her 2019 bequest, Jayne Wrightsman gave the Morgan a group of forty-one letters and documents that provide a record of French court life from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. Over two-thirds of the documents were written or signed by women, including two queens of France, Marie Leszczyńska and Marie-Antoinette; Josephine, empress of France; Henrietta Maria, queen of England; Maria Theresa, empress of Austria; Catherine the Great, empress of Russia; and Madame de Pompadour, one of the most renowned courtiers of the ancien régime. The pair of documents shown here are signed by two significant women during the reign of Louis XIV: his mistress Madame de Montespan (left) and his second wife, Madame de Maintenon (right).

Françoise-Athénaïs de Rochechouart, marquise de Montespan (1641–1707)

Document authorizing the apprenticeship of Marie-Anne de la Motte to a tailor

Convent of St. Joseph, Paris, 9 February 1689

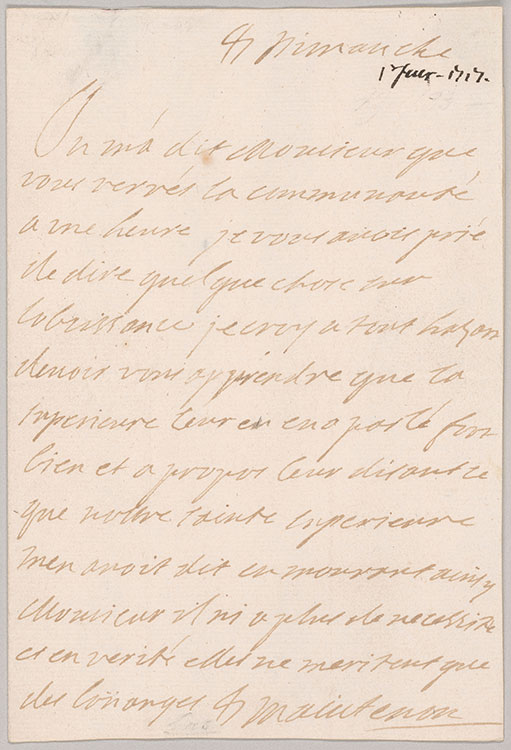

Françoise d’Aubigné, marquise de Maintenon (1635–1719)

Letter to Charles-François des Montiers de Mérinville (1682–1746), bishop of Chartres, place unknown, 1 June 1717

Gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1993; MA 4801 (27) and (22)

Pompadour's Library

Madame de Pompadour’s library contained over thirty-five thousand books, making it one of the largest literary repositories of the ancien régime. Her affinity for high-end works of art and luxury items extended to her books, many of which were lavishly decorated. On this binding, Douceur added red accents at the corners and within individual flowers to highlight the dentelle. Among Pompadour and her peers, books were often displayed with prominence as objets d’art—as Jayne Wrightsman lived with them—of which this colored and delicately gilt binding is an excellent example.

Bound for Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, marquise de Pompadour (1721–1764)

Louis Douceur (d. 1769), binder

Dark green morocco, with red morocco mosaic inlays, and gilt dentelle and armorial, on: Charles-Jean-François Hénault (1685–1770) Chronologique de l’histoire de France, 1752

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1910; PML 17282

Pompadour's Rodogune

Madame de Pompadour commissioned Boucher to illustrate the edition of Pierre Corneille’s play Rodogune, first published in 1647, that she was having printed at Versailles (on view in the case below). The frontispiece illustrates the climax of the play, when both Cleopatra, queen of Syria, and Rodogune, a Parthian princess, accuse each other of the murder of Seleucus. Boucher drew the scene from two vantages, which were later combined into a single composition. The original engraving, seen in the proof print to the right, was produced by Pompadour and then touched up for the final printing by Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger.

François Boucher (1703–1770)

Rodogune (Act V, Scene IV), ca. 1758–59

Black and white chalk on blue-gray paper

Purchased in 1927; III, 104a

Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, marquise de Pompadour (1721–1764), engraver, after François Boucher (1703–1770)

Proof impression of frontispiece for Rodogune, ca. 1758–59

Etching

Gift of Walter and Nesta Spink in honor of Charles Ryskamp; 2000.58

Mesdames De France

Adélaïde, Victoire, and Sophie were daughters of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska. The sisters held significant positions at court; Adélaïde, for example, served as an advisor both to her father and to her nephew Louis XVI. The bindings of the Mesdames are differentiated by color: Adélaïde’s are bound in red morocco, Victoire’s in green, and Sophie’s in yellow (citron). The diamond-shaped armorial of the fille de France (daughter of France) is the same for each, however. Of the three sisters, Adélaïde had the most extensive library—over eleven thousand volumes, surpassed only by the collection of Madame de Pompadour. Adélaïde’s books are richly decorated, demonstrating nearly every stylistic technique practiced by contemporary binders.

Bound for Madame Adélaïde (1732–1800)

Pierre-Paul Dubuisson (act. 1746–62), binder

Red morocco, with gilt plaque border, and painted armorial under mica, on: Almanach royal, 1757

PML 198427