Jayne Wrightsman: Collector and Benefactor

Jayne Wrightsman was a supporter of the Morgan for over forty years. This section highlights a few of her gifts to the Morgan, not only the 2019 bequest but also her earlier donations and purchased gifts to the Departments of Drawings and Prints, Literary and Historical Manuscripts, and Printed Books and Bindings. Wrightsman’s donations in the visual arts have ranged from formal compositions, such as the depiction of a caryatid by Charles Le Brun, to informal sketches like those Gabriel Jacques de Saint-Aubin drew in auction catalogues. The Wrightsman bindings provide a thorough record of French luxury binding from the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth century and preserve the exceptional work of artisans whose names and identities have been largely unrecorded. The bindings, the works they contain, and other documents from the Wrightsman collection help to form a fuller picture of the ancien régime at its height.

Jayne Wrightsman lived with her collection. Her books were not hidden away in bookcases but on display throughout her Manhattan apartment, intended as objects to be examined and admired as one would a fine sculpture or painting. This furniture installation provides a glimpse of her rarified yet personal environment.

Hand-painted wallpaper courtesy of de Gournay

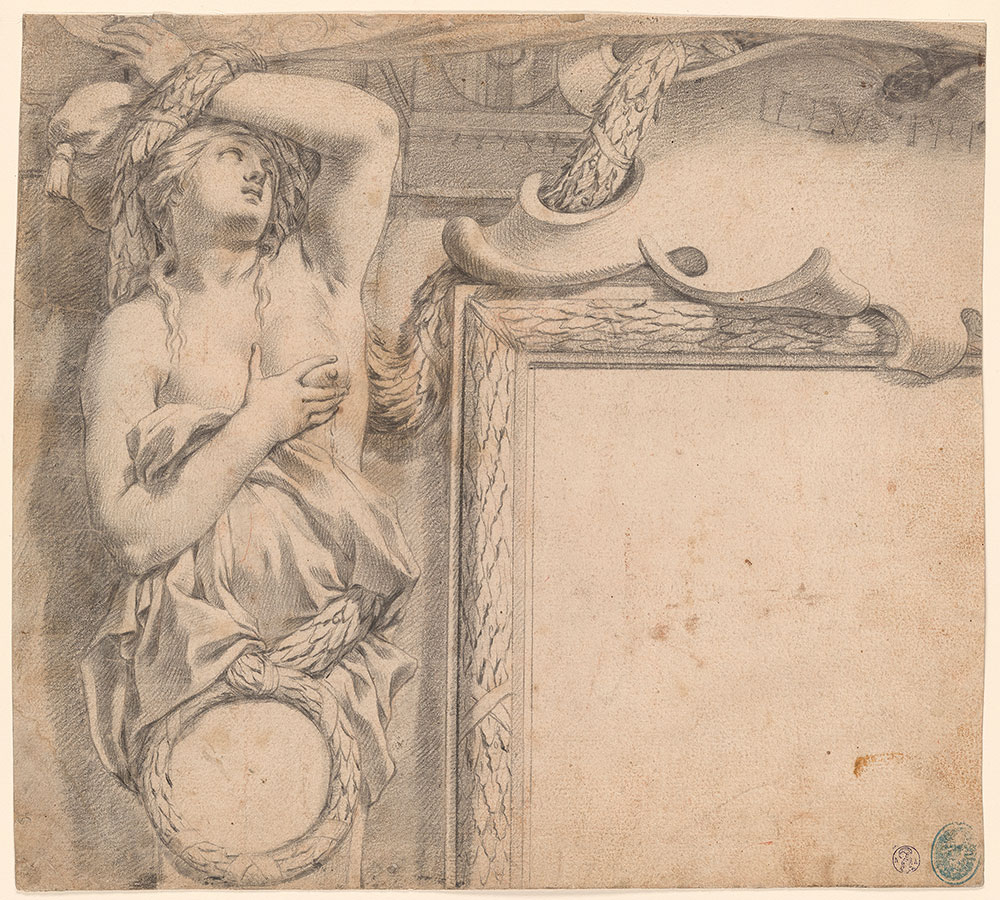

Le Brun’s Grand Design

This is one part of a larger composition for a decorative frame, engraved in 1642 but never printed. The drawing represents the left side of the frame, which features a caryatid, a draped female figure symbolizing peace and abundance, supporting the upper border. The lower border (see figure below) depicts the gods Mars and Apollo holding a mantle with the armorial of Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal Richelieu (1585–1642), chief minister to Louis XIII. Le Brun was one of the founding members of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, established in 1648, and he was later appointed painter to the king.

Charles Le Brun (1619–1690)

A Caryatid, ca. 1641–42

Black chalk on paper; incised for transfer

Purchased as the gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman; 1987.6

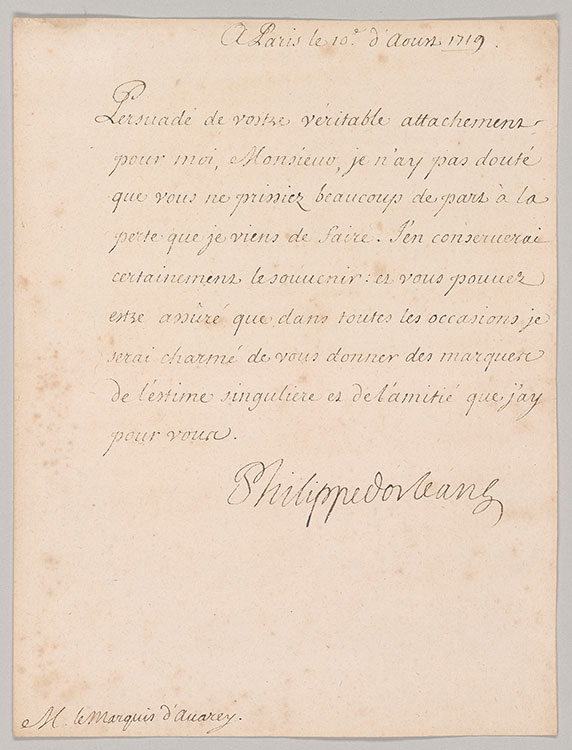

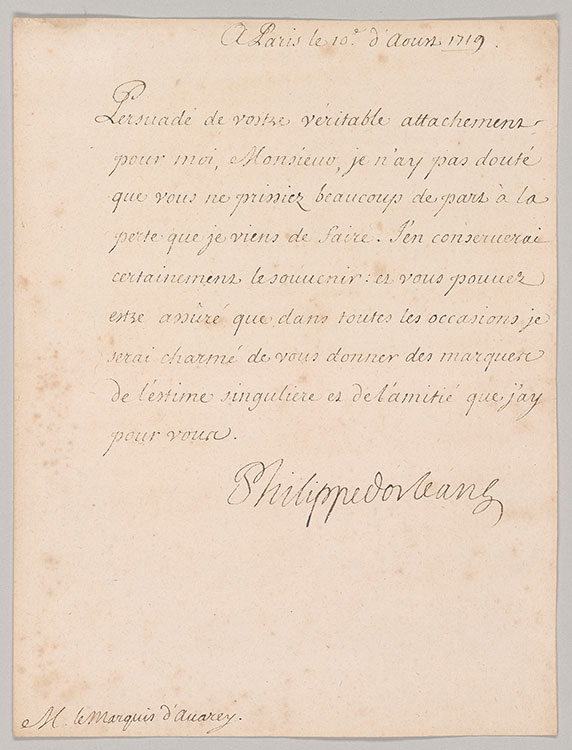

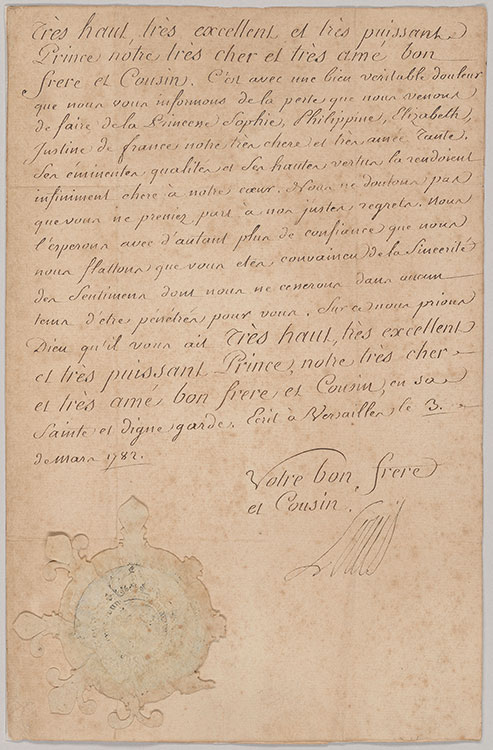

The King and the Regent

Among Jayne Wrightsman’s donations to the Morgan was a group of forty-one letters and documents signed by various members of the French court and other major European royal houses from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. The letter on the left, signed by Louis XVI and bearing an embossed royal seal, informs George III of the death of Louis’s aunt, Madame Sophie (whose yellow-bound books are on view elsewhere in the exhibition). At right, Philippe II thanks the marquis d’Avaray for his condolences at the death of Philippe’s daughter Marie-Louise, duchesse de Berry (1695–1719). The close relationship between father and daughter instigated many rumors and may have inspired Voltaire’s play Oedipus.

Louis XVI, king of France (1754–1793)

Letter to George III, king of Great Britain (1738–1820), Versailles, 3 March 1782

Philippe II, duc d’Orléans, regent of France (1674–1723)

Letter to Claude Théophile de Béziade, marquis d’Avaray (1655–1745), Paris, 10 August 1719

Gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1993; MA 4801 (20) and (30)

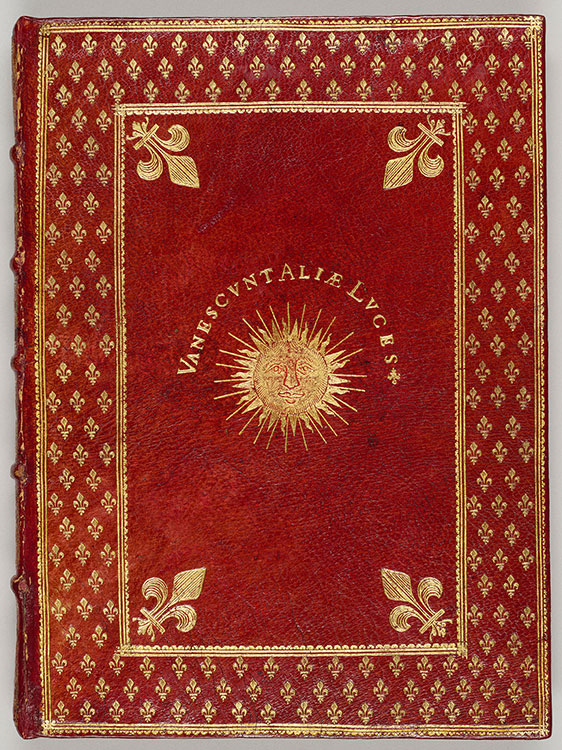

"Other Lights Fade"

Chastelet dedicated his political treatise and its exceptional binding to Louis XIV, “the Sun King.” The motto across the cover, Vanescunt aliae luces (Other lights fade), was likely invented by Chastelet to reflect Louis’s grandeur more appropriately, since the text makes a point of criticizing the king’s traditional motto, Nec pluribus impar (translated literally, “Not unequal to many”)—a head-scratching double negative that many found obscure. Despite Chastelet’s

attempts at flattery, the treatise landed him in jail for suggesting several social and economic reforms to address the growing ills that he had observed in prerevolutionary France.

Dedicated and bound for Louis XIV (1638–1715)

Red morocco, with gilt tooling and motto, on: Paul Hay du Chastelet (1620?–1682?)

Observations sur le traité de la politique de France, ca. 1669

Manuscript on paper

MA 23401