Bound for Versailles: The Jayne Wrightsman Bookbindings Collection

Jayne Wrightsman (1919–2019) was a renowned art collector, a celebrated philanthropist to New York cultural institutions, and a fashion icon. Around 1950, Wrightsman and her husband, Charles (1895–1986), became interested in the art and interiors of eighteenth-century France. In a design scheme she described as “Marie-Antoinette-ing it up,” Wrightsman set out to redecorate the couple’s homes in courtly fashion, furnishing them with a growing number of artworks, including French books and bindings that comprised a core part of this expanding collection. The books—monuments of fine printing, illustration, and bookbinding were displayed centrally amid the couple’s Versailles-inspired interiors, accompanying gilded furniture, parquet floors, paintings, sculpture, and other objets d’art. Seen together, this exquisite ensemble formed a stunning tableau in celebration of the French decorative arts.

In the spring of 2019, Wrightsman bequeathed her book collection to the Morgan, an institution she had supported for many years as a donor and trustee. Bound for the highest echelons of eighteenth-century French society, the books once belonged to kings, queens, dukes, and duchesses. This exhibition honors Jayne Wrightsman’s gift and her collecting acumen by examining the bound book as a fixture of French courtly life during the ancien régime, and recognizing its integral relationship to the period’s broader artistic and intellectual developments. The Wrightsman gift expands and supports the Morgan’s existing collection of French books and bindings, established through the generosity of the institution’s founder, J. Pierpont Morgan, and benefactors such as Dannie and Hettie Heineman, Gordon N. Ray, Beatrice Bishop Berle, and Julia P. Wightman.

Bound for Versailles: The Jayne Wrightsman Bookbindings Collection is made possible with support from the Jamie and Maisie Houghton Fund and the Parker Gilbert Fund, and with assistance from Barbara G. Fleischman and the Malcolm Hewitt Wiener Foundation.

Unless otherwise designated, all objects in the exhibition are from the Morgan Library & Museum and were donated by Mrs. Jayne Wrightsman in honor of Mrs. Annette de la Renta.

Overview

Gallery Images

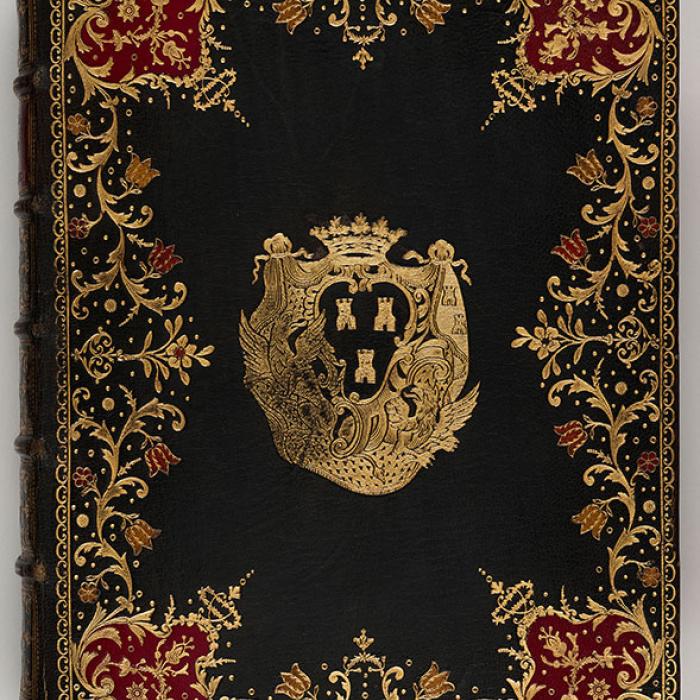

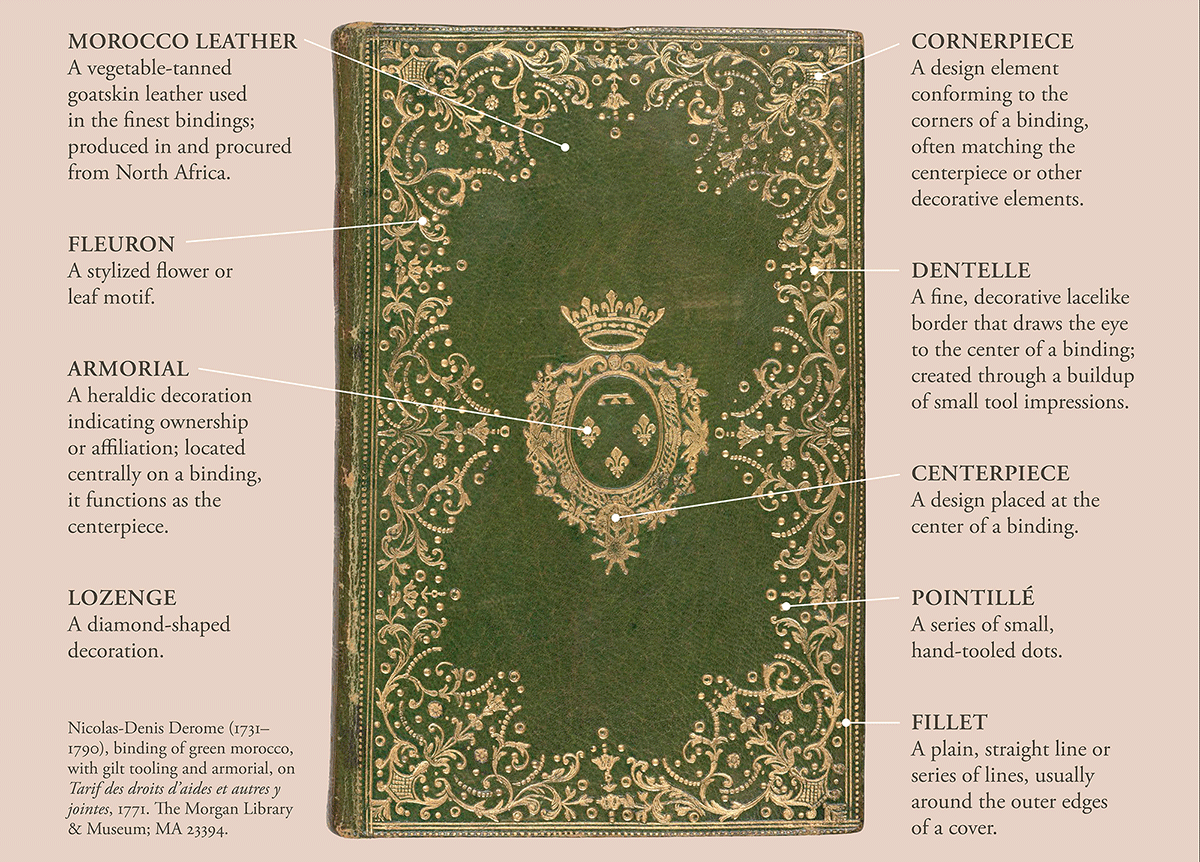

The Art of Book Decoration

Finishing—the final phase of a bookbinder’s work—involves the ornamentation of the leather binding with an assortment of hand tools. The binder typically uses gold leaf, a thin gold sheet, which is laid over the book and impressed repeatedly with tools to pattern the cover—a process known as gilt tooling. The bookbinders of eighteenth-century France, influenced by the decorative styles of the times, advanced the art of finishing to new heights of ornamental luxury. This trend is evident in the work of the royal bookbinder (relieur du roi), of which three are of note: Antoine-Michel Padeloup (1685–1758), Pierre-Paul Dubuisson (act. 1746– 62), and Nicolas-Denis Derome (1731–1790). As masters of the craft, they could turn an inchoate set of materials—blank expanses of supple leather, gold leaf, and myriad decorative tools—into compelling and exuberant compositions.

The work of bookbinding was usually carried out in a binder’s workshop, or atelier, which employed a team of skilled assistants—male and female—to oversee the technical and decorative aspects of production. Attributing a binding to a specific atelier can be difficult, as bindings were infrequently signed and identifying tools were often shared within a family of binders. In the eighteenth century, an ever-growing number of book collectors and personal libraries expanded the bookbinding enterprise. Workshops became commonplace in and around Paris, and we know the names of many binders for whom there is no identified work. The bindings that survive from this age of plenty reflect both the skill of their creators and the fine taste of their collectors.

Bookbinding Terms

BOOKBINDING TERMS

MOROCCO LEATHER

A vegetable-tanned goatskin leather used in the finest bindings; produced in and procured from North Africa.

CORNERPIECE

A design element conforming to the corners of a binding, often matching the centerpiece or other decorative elements.

FLEURON

A stylized flower or leaf motif.

DENTELLE

A fine, decorative lacelike border that draws the eye to the center of a binding; created through a buildup of small tool impressions.

ARMORIAL

A heraldic decoration indicating ownership or affiliation; located centrally on a binding, it functions as the centerpiece.

CENTERPIECE

A design placed at the center of a binding.

POINTILLÉ

A series of small, hand-tooled dots.

LOZENGE

A diamond-shaped decoration.

FILLET

A plain, straight line or series of lines, usually around the outer edges of a cover.

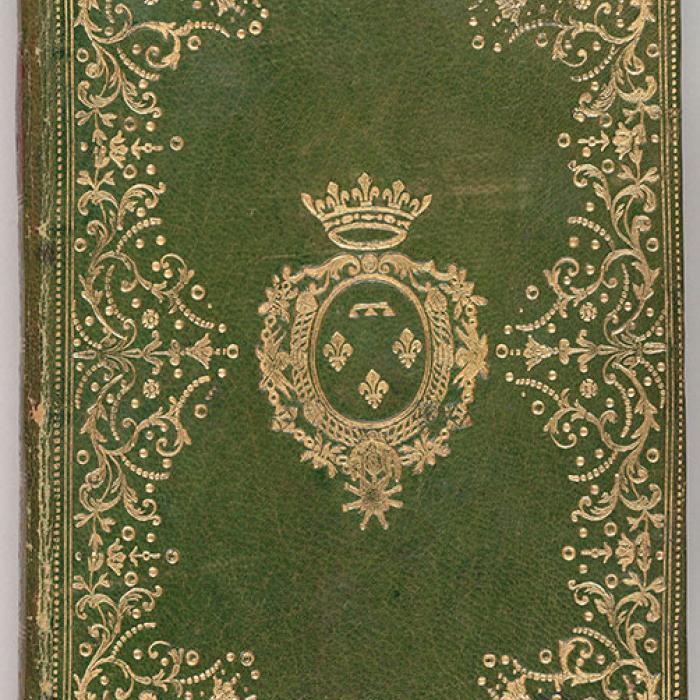

Nicolas-Denis Derome (1731–1790), binding of green morocco, with gilt tooling and armorial, on Tarif des droits d’aides et autres y jointes, 1771. The Morgan Library & Museum; MA 23394.

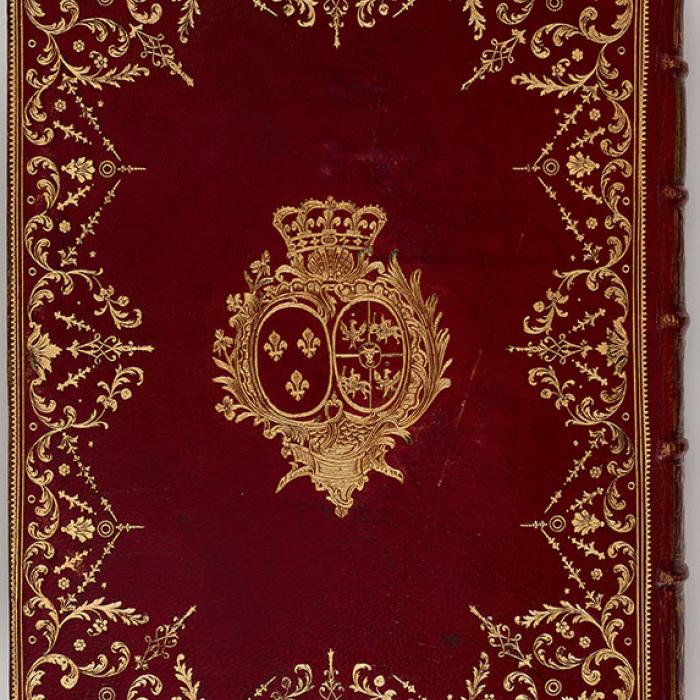

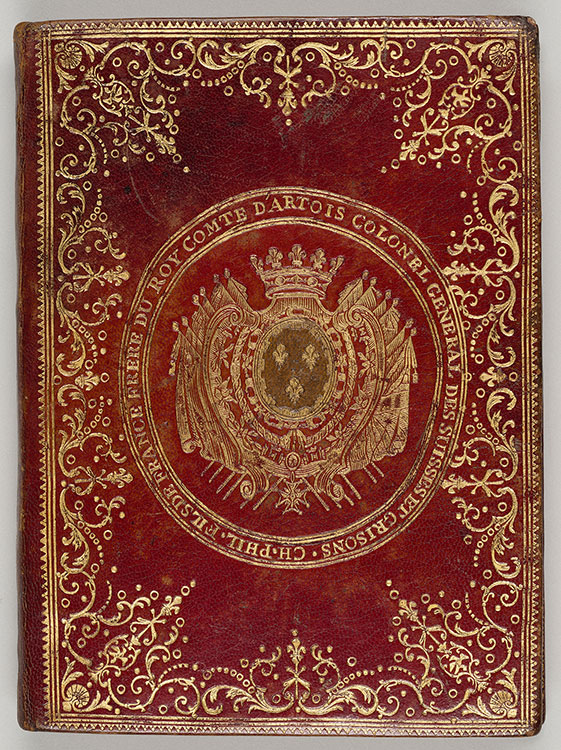

Armorials and Individual Tooling

On the bindings at left and center, the binder had to take into account the size of the armorial when producing the dentelle. The two elements are not meant to compete but should instead form a single, cohesive composition. An ill-fitting armorial is a sign of poor planning or perhaps a later addition—as in the remboîtage, or repurposed binding, at right. This binding was removed from an unknown book, added on to a nineteenth-century text, then tooled with a large armorial that dominates and disrupts the initial, harmonious design. Hidden in each corner of the dentelle is an oiseau, or bird, the signature tool of the renowned original binder, Nicolas-Denis Derome.

Bound for Louis-Philippe I, duc d’Orléans (1725–1785)

Nicolas-Denis Derome (1731–1790), binder

Green morocco, with individual gilt tooling, on: Tarif des droits d’aides et autres y jointes, 1771

MA 23394

Remboîtage binding for Charles-Philippe, comte d’Artois (1757–1836)

Nicolas-Denis Derome (1731–1790), original binder

Red morocco, with individual gilt tooling and later armorial, on: Collection of Verse, 1821

MA 23404

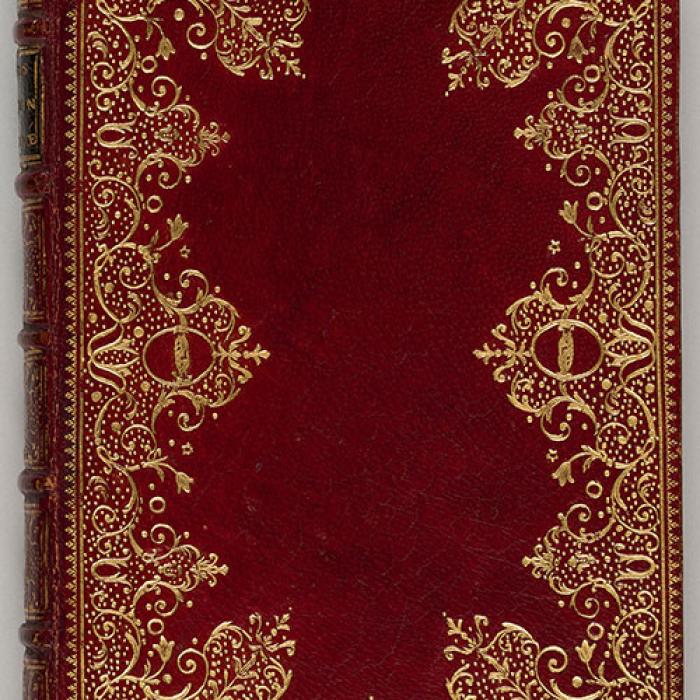

Individual Tooling

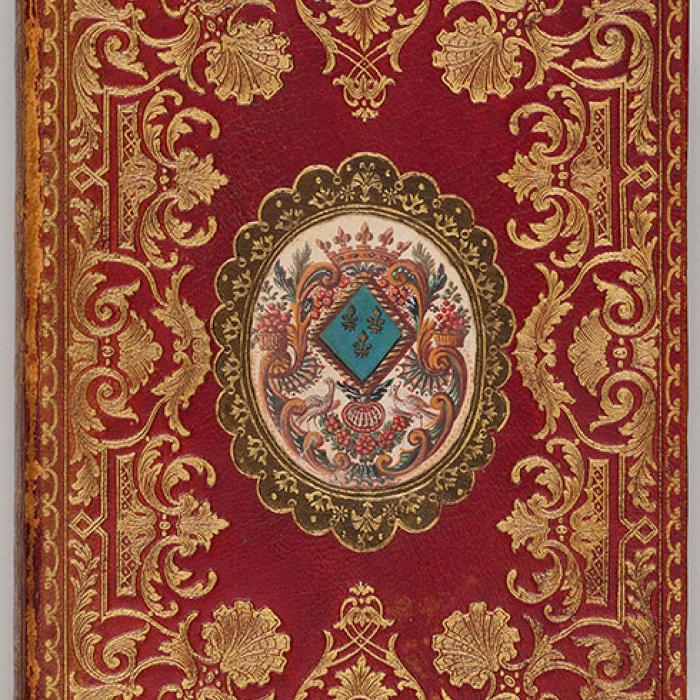

The bindings displayed here are examples of intricate, well-planned design work. Decorative borders are symmetrical and necessitate detailed measurements and exacting tooling to ensure a balanced composition. The bindings have deep dentelles that both encroach upon and highlight the clean expanse of red morocco. Interstitial areas between fleurons and leaves are filled with pointillé and lozenge tools to create a more sumptuous design.

Red morocco, with gilt dentelle, in the style of Antoine-Michel Padeloup (1685–1758), on: Les amours pastorales de Daphnis et Chloé, 1718

PML 198330

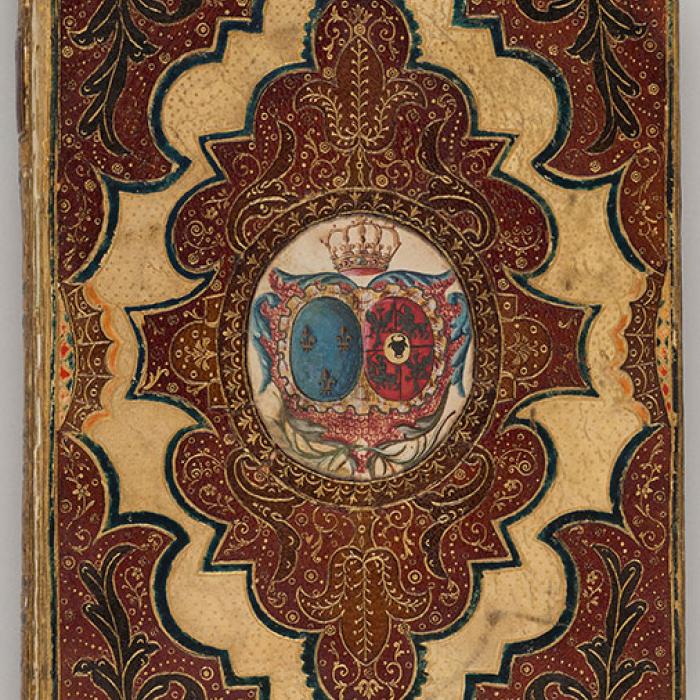

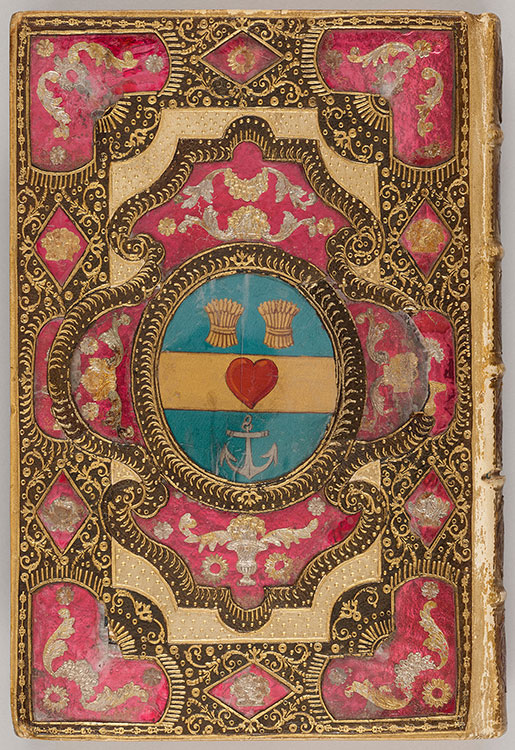

Beyond Gold: Mosaic, Painted, and Foil Decoration

The mastery of gold leaf is but one skill in the binder’s decorative repertoire. Mosaic binding is another, more exacting finishing method. The inlay mosaic technique (seen on the first three bindings) involves cutting out a figural shape from the covering leather, then replacing it with an alternate piece of the same size and thickness but a contrasting color or grain. In the onlay technique, the contrasting leather pieces are laid over the covering leather, appearing in relief. Both methods can create elaborate decorative or narrative scenes.

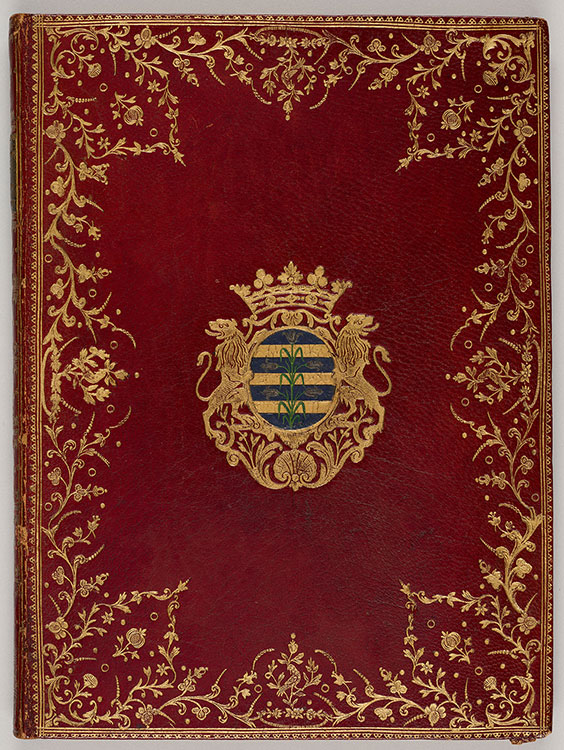

The painted leather armorial is another decorative option, as seen on the fourth binding. The fifth binding combines cutout leather and gold and silver foil on a background of red foil. Sheets of mica, a clear silica material, protect the exposed painted areas and reflective foil.

Bound for Queen Marie Leszczyńska (1703–1768)

Jacques-Antoine Derome (1696–1760), binder

Mosaic binding in cream, black, and red morocco, with individual gilt tooling, on: Le psautier de David, 1725

PML 198290

Bound for an unidentified marquis

Perhaps Louis Douceur (d. 1769), binder

Red morocco, with individual gilt tooling and painted armorial, on: Pierre-Annet de Pérouse (1699–1763)

Extrait de l’histoire généalogique de la maison de Beaumont, 1757

PML 198348

Bound for Pierre-Louis-Paul Randon de Boisset (1708–1776)

Nicolas-Denis Derome (1731–1790), binder

Cut binding in cream and black morocco, with individual gilt tooling, and gold, silver, and red foil under mica, on: Almanach royal, année M. DCC. LXV, 1765

PML 198429

Jayne Wrightsman: Collector and Benefactor

Jayne Wrightsman was a supporter of the Morgan for over forty years. This section highlights a few of her gifts to the Morgan, not only the 2019 bequest but also her earlier donations and purchased gifts to the Departments of Drawings and Prints, Literary and Historical Manuscripts, and Printed Books and Bindings. Wrightsman’s donations in the visual arts have ranged from formal compositions, such as the depiction of a caryatid by Charles Le Brun, to informal sketches like those Gabriel Jacques de Saint-Aubin drew in auction catalogues. The Wrightsman bindings provide a thorough record of French luxury binding from the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth century and preserve the exceptional work of artisans whose names and identities have been largely unrecorded. The bindings, the works they contain, and other documents from the Wrightsman collection help to form a fuller picture of the ancien régime at its height.

Jayne Wrightsman lived with her collection. Her books were not hidden away in bookcases but on display throughout her Manhattan apartment, intended as objects to be examined and admired as one would a fine sculpture or painting. This furniture installation provides a glimpse of her rarified yet personal environment.

Hand-painted wallpaper courtesy of de Gournay

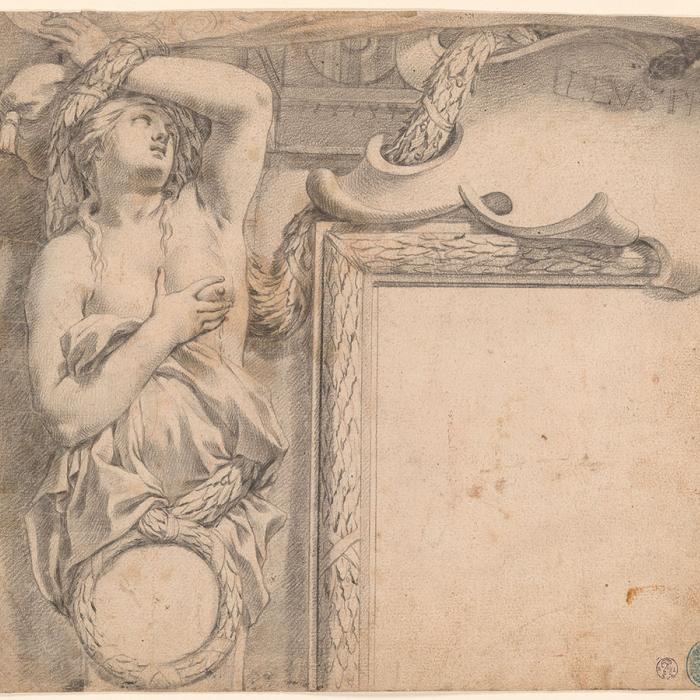

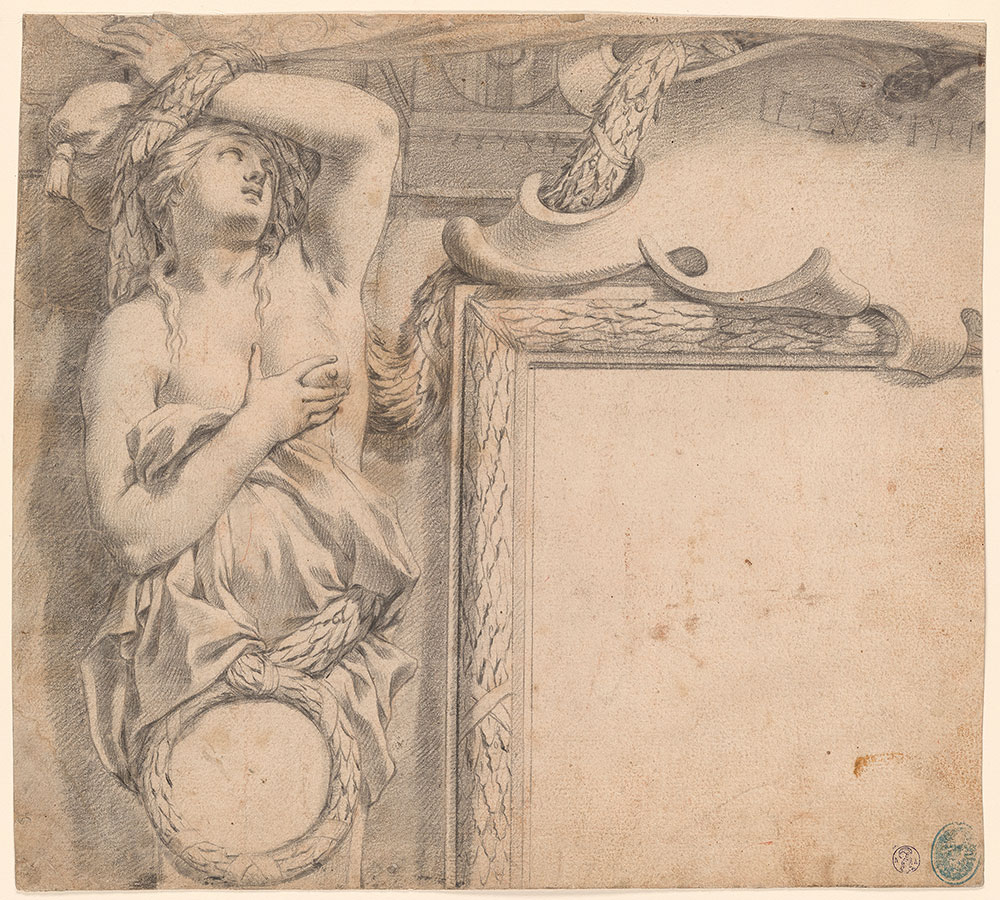

Le Brun’s Grand Design

This is one part of a larger composition for a decorative frame, engraved in 1642 but never printed. The drawing represents the left side of the frame, which features a caryatid, a draped female figure symbolizing peace and abundance, supporting the upper border. The lower border (see figure below) depicts the gods Mars and Apollo holding a mantle with the armorial of Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal Richelieu (1585–1642), chief minister to Louis XIII. Le Brun was one of the founding members of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, established in 1648, and he was later appointed painter to the king.

Charles Le Brun (1619–1690)

A Caryatid, ca. 1641–42

Black chalk on paper; incised for transfer

Purchased as the gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman; 1987.6

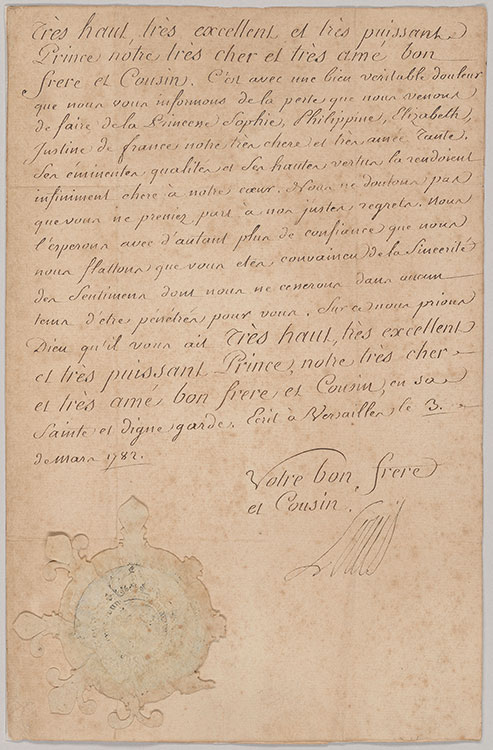

The King and the Regent

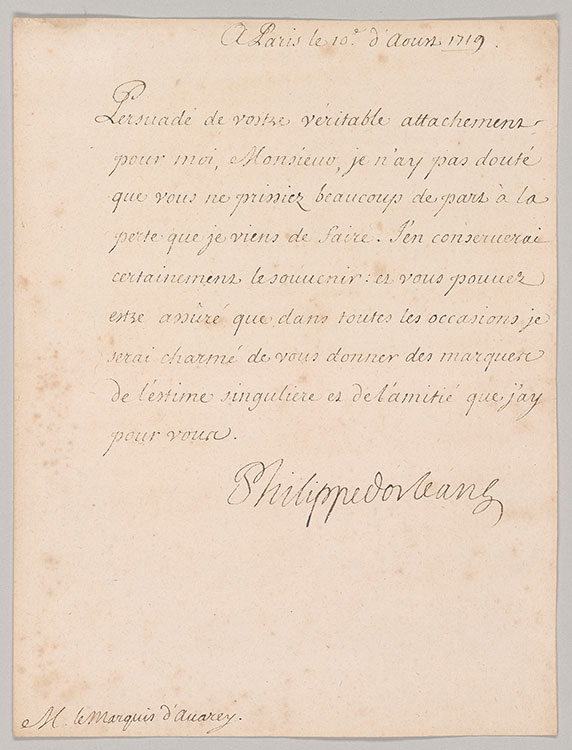

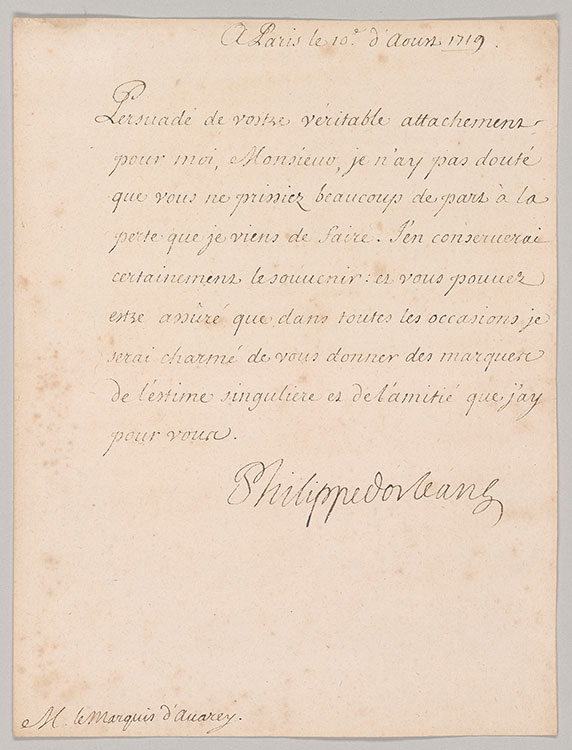

Among Jayne Wrightsman’s donations to the Morgan was a group of forty-one letters and documents signed by various members of the French court and other major European royal houses from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. The letter on the left, signed by Louis XVI and bearing an embossed royal seal, informs George III of the death of Louis’s aunt, Madame Sophie (whose yellow-bound books are on view elsewhere in the exhibition). At right, Philippe II thanks the marquis d’Avaray for his condolences at the death of Philippe’s daughter Marie-Louise, duchesse de Berry (1695–1719). The close relationship between father and daughter instigated many rumors and may have inspired Voltaire’s play Oedipus.

Louis XVI, king of France (1754–1793)

Letter to George III, king of Great Britain (1738–1820), Versailles, 3 March 1782

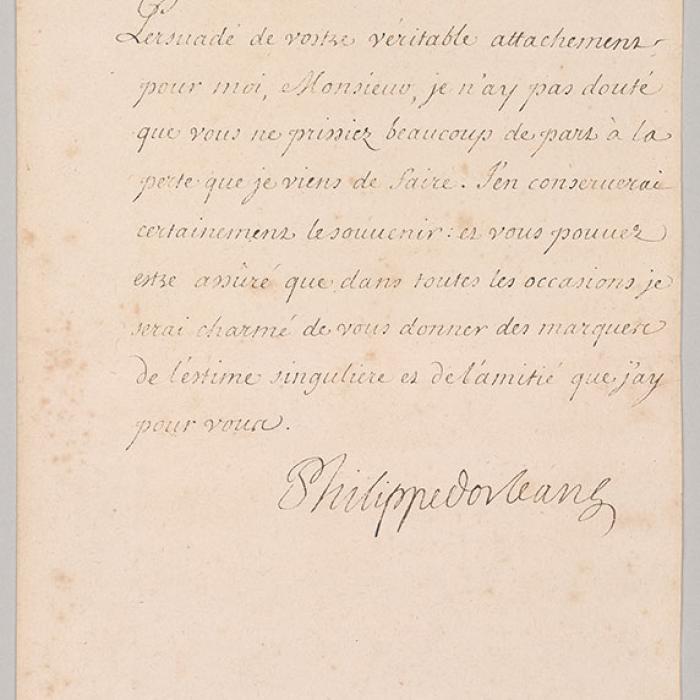

Philippe II, duc d’Orléans, regent of France (1674–1723)

Letter to Claude Théophile de Béziade, marquis d’Avaray (1655–1745), Paris, 10 August 1719

Gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1993; MA 4801 (20) and (30)

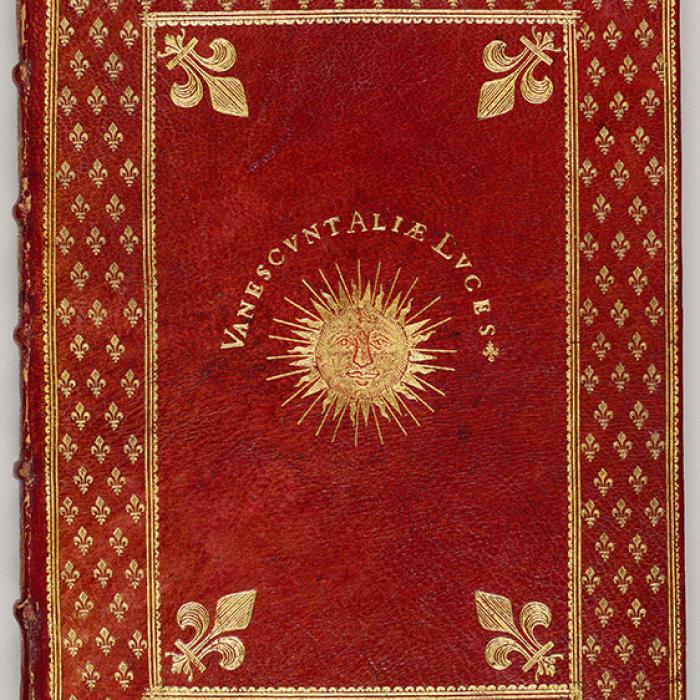

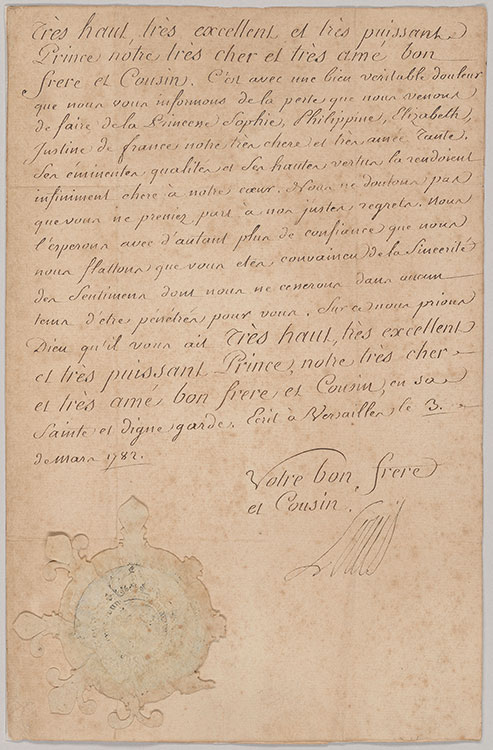

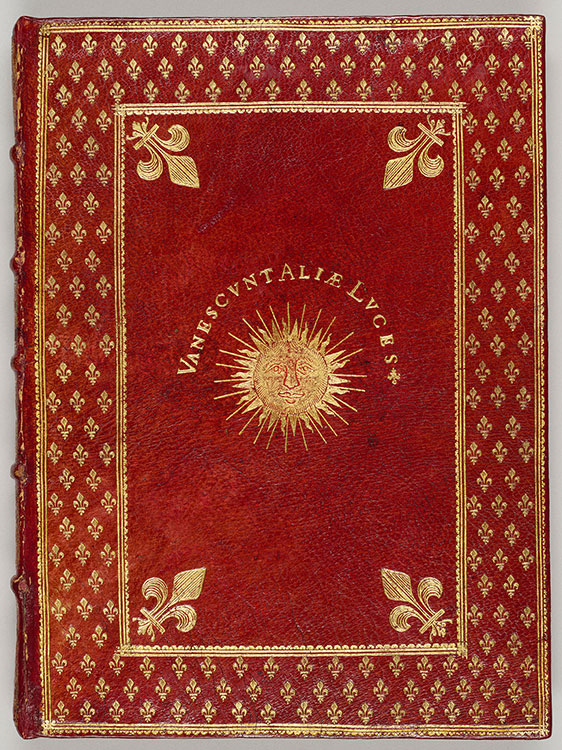

"Other Lights Fade"

Chastelet dedicated his political treatise and its exceptional binding to Louis XIV, “the Sun King.” The motto across the cover, Vanescunt aliae luces (Other lights fade), was likely invented by Chastelet to reflect Louis’s grandeur more appropriately, since the text makes a point of criticizing the king’s traditional motto, Nec pluribus impar (translated literally, “Not unequal to many”)—a head-scratching double negative that many found obscure. Despite Chastelet’s

attempts at flattery, the treatise landed him in jail for suggesting several social and economic reforms to address the growing ills that he had observed in prerevolutionary France.

Dedicated and bound for Louis XIV (1638–1715)

Red morocco, with gilt tooling and motto, on: Paul Hay du Chastelet (1620?–1682?)

Observations sur le traité de la politique de France, ca. 1669

Manuscript on paper

MA 23401

The Illustrated Book

The eighteenth century was a high point in French book production, elevated by tastes and trends in printed illustration. Through the literary text, engraved illustrations, and luxury binding, a book provided its owner with three degrees of cultural prestige. The collaboration of highly trained illustrators, painters, and engravers made this an exceptional period for the visual interpretation of the literary imagination.

Engraving is an intaglio printing process in which lines incised on a metal plate are filled with ink and then impressed on paper, transferring the design. The intensity of the printed line depends on the thickness or depth of the incised groove, and in this way the engraving process is closest to drawing. Practiced in Europe since the fifteenth century, engraving was developed to an exceptional standard during the eighteenth century. The subtle shading and textures in drawings by artists like François Boucher and Jean-Baptiste Oudry could now be reproduced by skilled engravers, such as Charles-Nicolas Cochin (father and son). volumes were devoted solely to engraved illustrations recording and promoting French architecture, contemporary fashion, and court spectacle.

Boucher's Frontispiece for Macswiny

Boucher composed this sweeping allegorical frame as one of the frontispieces in Owen MacSwiny’s Tombs of Princes, Great Captains, and Other Illustrious Men, a volume of engravings featuring allegorical tombs of notable Englishmen. This composition introduced the tomb of Sidney Godolphin (1645–1712), a British politician instrumental in negotiating the Acts of Union in 1707, which established Great Britain as a political entity. Boucher’s frame was ultimately engraved by Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger for the print publication.

François Boucher (1703–1770)

Design for frontispiece to “Tombeau du comte Sidney Godolphin,” ca. 1735–36

Pen and black ink, and gray and brown wash, heightened with white chalk, over black chalk

Purchased as the gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman in honor of Mrs. Charles W. Engelhard; 1985.68

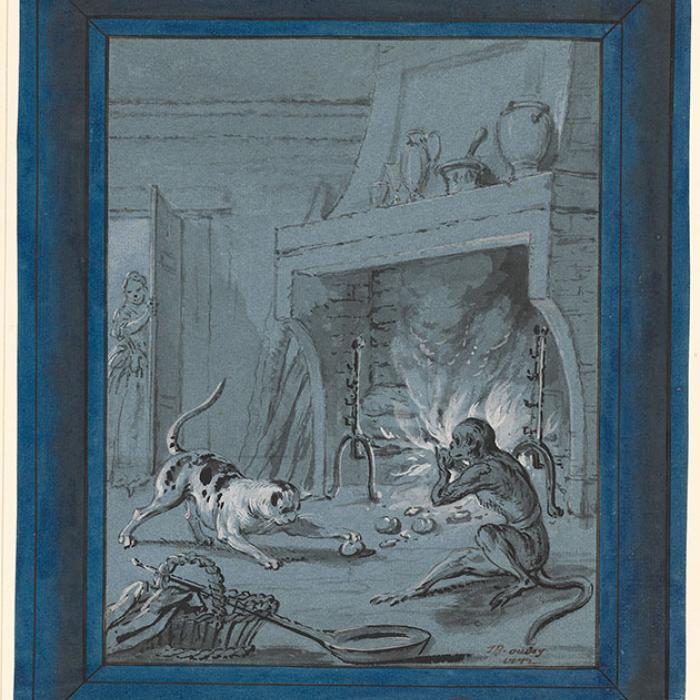

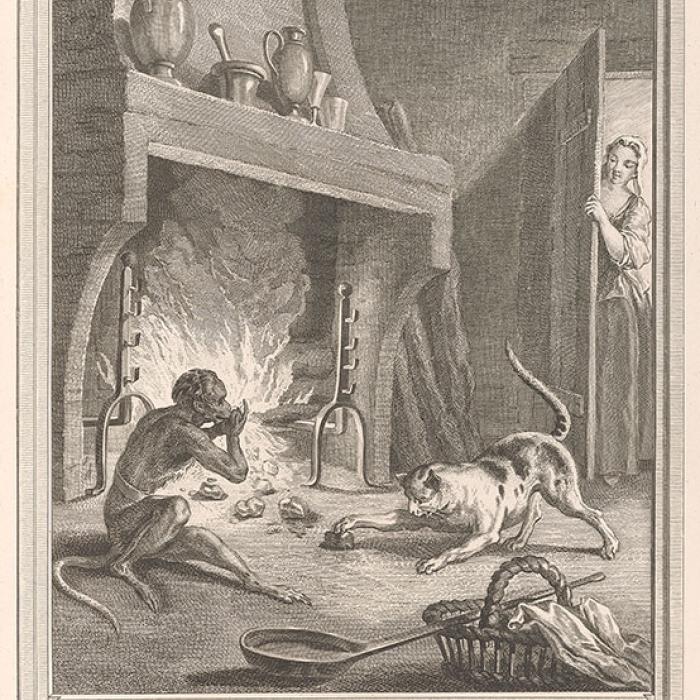

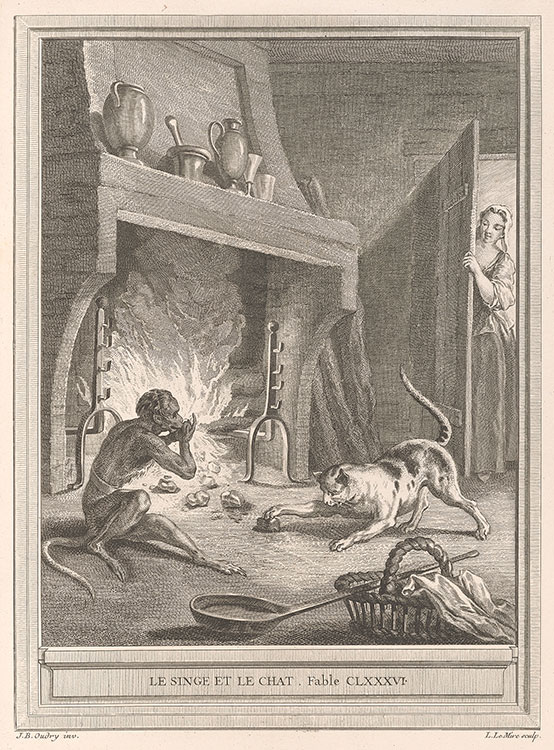

Oudry’s Fables

Jean-Baptiste Oudry was a portrait painter who was also well known for his ability to render animals. This is likely why he was inspired in 1729–34 to compose 277 drawings based on the animal fables of Jean de La Fontaine (1621–1695). Oudry made these compositions for his own artistic practice and enjoyment. Upon his death, however, the suite of drawings was acquired by the writer and editor Louis Regnard de Montenault (act. 1750–60), who used them to illustrate a monumental new printed edition of the Fables (in the center of the room). Montenault employed Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger to rework the drawings so that they could be more effectively converted into engravings.

Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686–1755)

The Monkey and the Cat, 1732

Black ink and gray wash, with white opaque watercolor, on blue paper

The English Fox, 1733

Black ink and gray wash, with white opaque watercolor, on blue paper

The Fortune Tellers, 1733

Black ink and gray wash, with white opaque watercolor, on blue paper

Purchased on the Fellows Fund; 1976.6–8

The Man Who Runs After Fortune and the Man Who Waits in His Bed, 1731

Black ink and gray wash, with white opaque watercolor, on blue paper

Gift of Charles Ryskamp

Fabulous Fables

La Fontaine’s Fables is one of the most ambitious, monumental book productions to emerge from eighteenth-century Paris. A celebration of French literature, engraving, and typography, it was not so much a book to read as one to collect for its artistic value. The Monkey and the Cat illustration was engraved by Louis Legrand (1723–1807) based upon the original Jean-Baptiste Oudry and Charles-Nicolas Cochin drawing (on the wall to your left). The composition, reversed through the engraving process, has a more detailed setting and intense play of light and shadow than the original, although the focus on the lively animals is diminished.

Jean de La Fontaine (1621–1695)

Fables choisies mises en vers, 4 vols.

Paris: Chez Desaint & Saillant, and Durand, 1755–59

PML 198445–48 (PML 198447 on view)

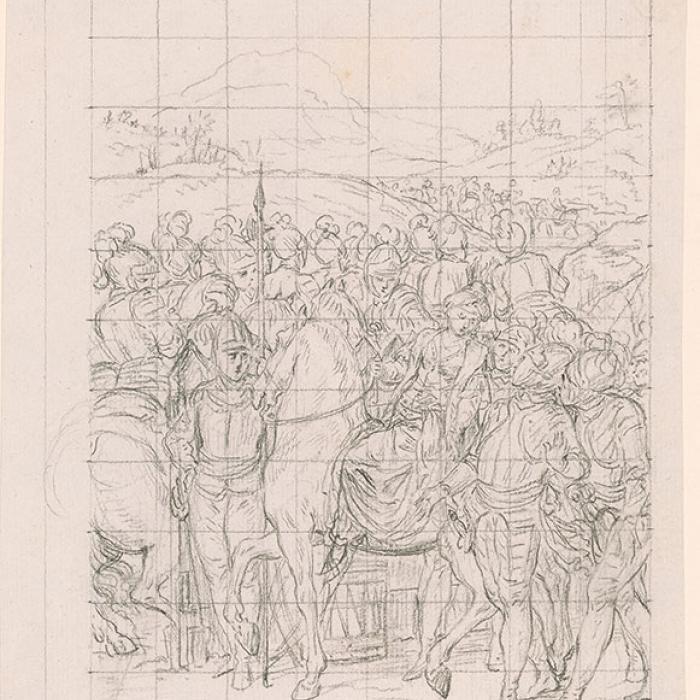

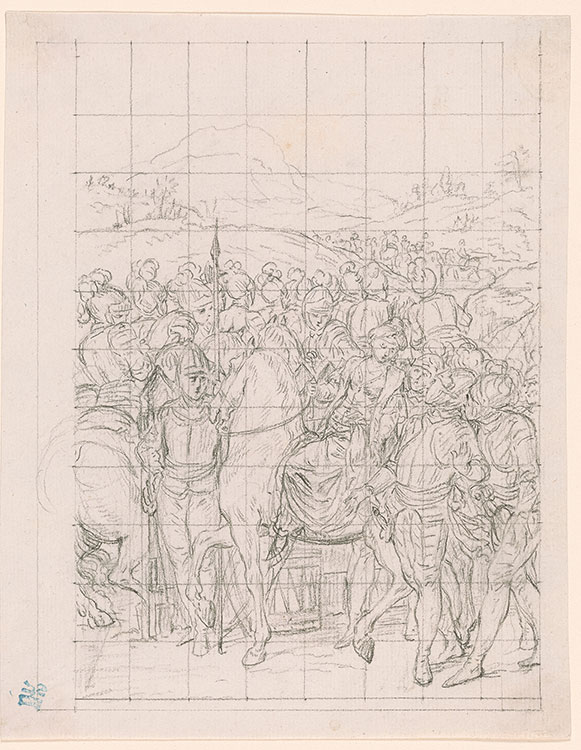

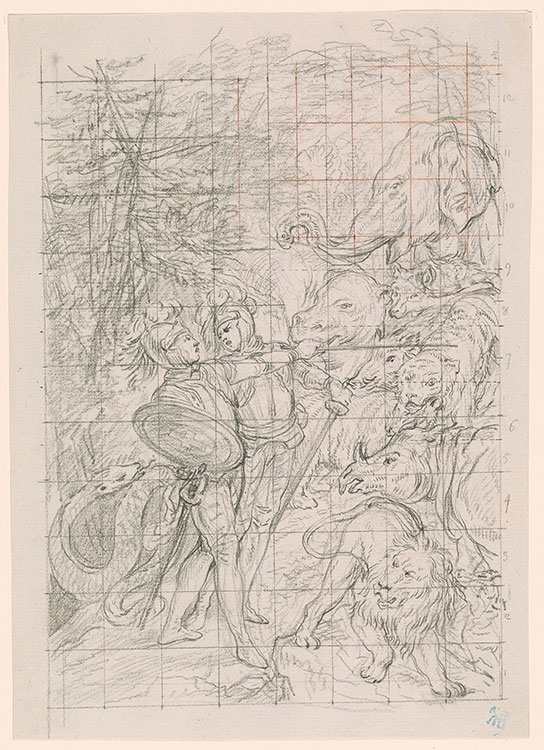

Epic Illustration

Louis Stanislas, comte de Provence, a younger brother of Louis XVI’s who later reigned as Louis XVIII, commissioned Cochin to illustrate a printed edition of the sixteenth-century epic Jerusalem Delivered by the Italian poet Torquato Tasso. Cochin produced forty-one full-page drawings and forty-one smaller head-and tailpiece illustrations, each of which earned him the considerable sum of five hundred francs. The superimposed grid on each sketch was to help enlarge and transfer the composition to a copper engraving plate. Cochin also produced more finished versions of each composition—likely to aid the engravers with details and shading—that were then gifted to Stanislas.

Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger (1715–1790)

Preparatory sketch for Ubaldo Driving Away the Wild Beasts with His Wand, ca. 1783–85

Black chalk on gray paper; squared in black chalk for transfer

Purchase; 1989.41:13

Preparatory sketch for Armida Departing, Leaving Behind the Crusaders as Her Prisoners, ca. 1783–85

Black chalk on gray paper; squared in black chalk for transfer

Purchase; 1989.41:5

Books at Court

As both works of art and symbols of status, books were held in high regard at the French court. A large library had its own cultural cachet, which could beenhanced through the decoration of its volumes’ pages or bindings. Books were mobile objects, allowing for their exchange as tokens of patronage. Authors could dedicate their work to a noble in hopes of gaining favor at court, and nobles often presented bound volumes to their supporters and retainers. Books were also a means of commemorating the court’s principal figures and events. This is exemplified by the volumes of opera and ballet scores in the Wrightsman collection, such as the sole surviving copy of the court composer André Danican Philidor’s La princesse de Crète, as well as by devotional works like the Hymne nouvelle, which was written and bound for Louis XIV.

Books were well integrated within the full display of decorative arts at Versailles—just as they were in Jayne Wrightsman’s home. In fact, bookbinding had a rather direct connection to the French court’s decor: the gilt dentelle borders surrounding an open expanse of leather mirrored in miniature the decorative frames of the wood paneling that lined the palace walls.

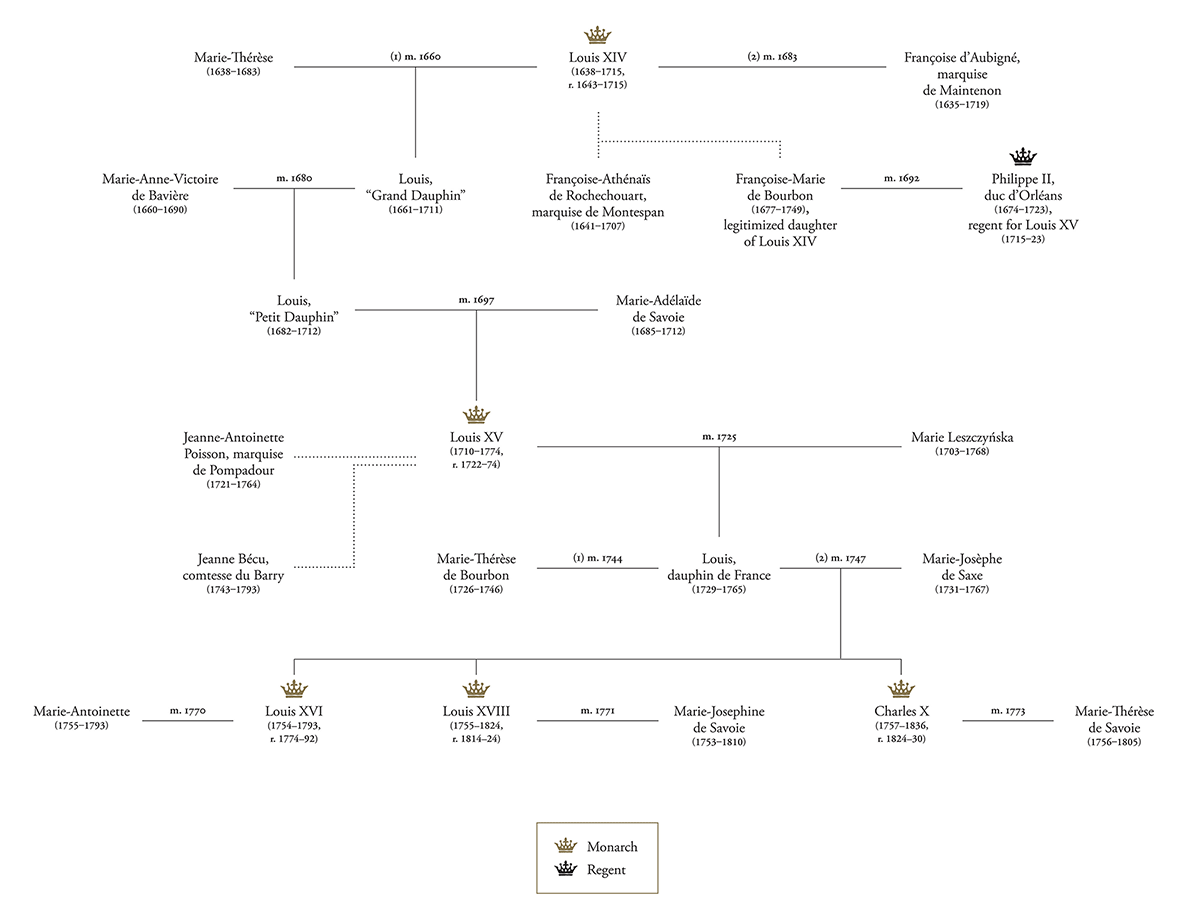

French Royal Family Tree

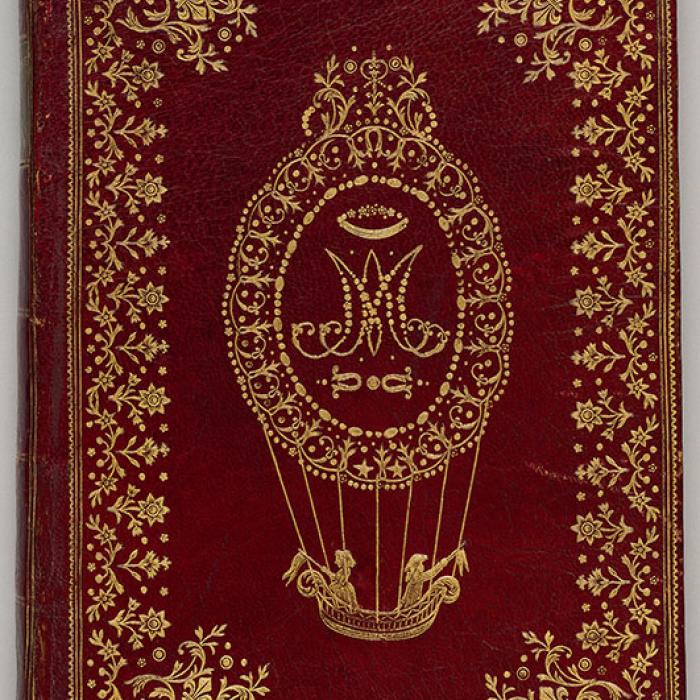

Joseph and Étienne Montgolfier

Around 1782, the Montgolfier brothers became among the first to develop the European hot-air balloon, or globe aérostatique, as they called it. As they came from a family of paper manufacturers in southern France, the brothers used materials like paper and taffeta in their early experiments to create the large pockets for hot air. This drawing by Boilly captures the expressions and personalities of the two brothers. Joseph, the elder and purportedly shier sibling, is portrayed behind the outgoing Étienne.

Louis-Léopold Boilly (1761–1845)

The Montgolfier Brothers, Joseph-Michel (1740–1810) and Jacques-Étienne (1745–1799), mid-1790s

Black chalk, heightened with white opaque watercolor

Gift of Stuart and Beverly Denenberg in honor of William M. Griswold; 2007.125

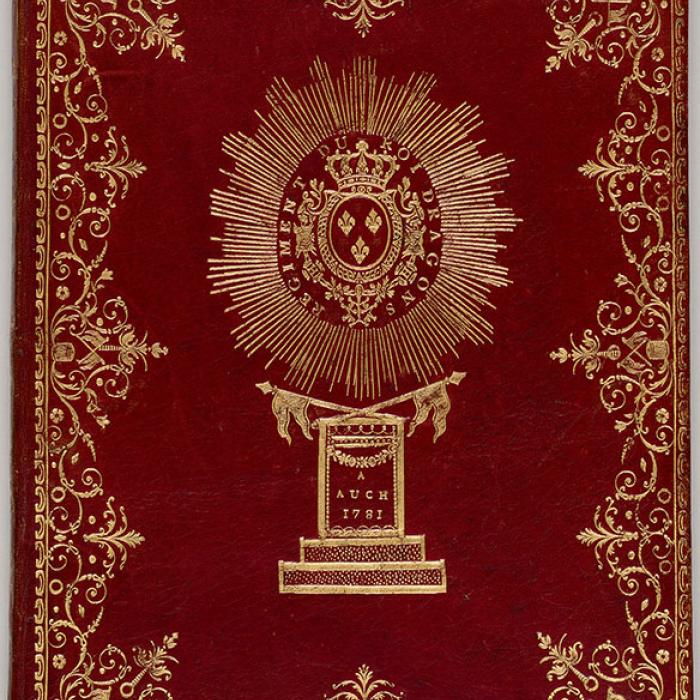

Bound For Louis Charles de la Baig, Comte de Viella (1744–1828)

Noé, bishop of Lescar, delivered this speech to the King’s Dragoons, an elite group of Louis XVI’s troops, after they had just returned from America. In September 1781, the dragoons aided George Washington’s army at the Battle of the Chesapeake, a critical turning point in the American Revolution that sealed the British general Charles Cornwallis’s defeat at Yorktown. This copy was bound for Noé’s nephew, Louis Charles de la Baig, who was the French unit’s

second-in-command under General Lafayette. The decorative elements in the dentelle commemorate the victorious dragoons, while a glorified France is literally placed on a pedestal.

Red morocco, with gilt tooling and armorial, on: Marc-Antoine de Noé (1724–1802)

Discours prononcé dans l’église métropolitain d’Auch, 1781

PML 198393

Commemorating a Royal Spectacle

The Montgolfier brothers’ experiments with hot-air balloons quickly drew the attention of the king. On 19 September 1783, they performed the first-ever flight at Versailles, sending up several farm animals as passengers. That October, Étienne became the first human test pilot, in a balloon decorated with Louis XVI’s face and monogram (see image at right). These two bindings commemorate that ascent, replacing Louis’s initials with those of Marie-Antoinette. The Montgolfier balloon made such an impact that the balloon globe became a visual element in all types of decorative arts and home accessories.

Bound for Marie-Antoinette (1755–1793)

Red morocco, with gilt tooling “à la Montgolfière” and monogram, on: Barthélemy Imbert (1747–1790)

Lecture du matin and Lecture du soir, 1782

PML 198378–79

Bound For Jean-baptiste Colbert, Marquis De Seignelay (1651–1690)

Colbert was minister of the navy under Louis XIV, a position he gained from his father, Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683), an influential secretary of state known as Le Grand Colbert. The younger Colbert inherited his father’s extensive library of over twenty thousand volumes. Although he was not too interested in expanding the collection, this volume is one of several that can be directly tied thim. Tachard, a Jesuit missionary and mathematician, wrote Voyage to Siam after several trips to the region (modern-day Thailand) as a French envoy; of interest to Colbert may have been the account’s firsthand insight into a place where France had imperialist aims.

Eloi Levasseur (act. 1636–1700), binder

Red morocco, with gilt armorial, on: Guy Tachard (1651–1712) Voyage de Siam, 1686

PML 198286

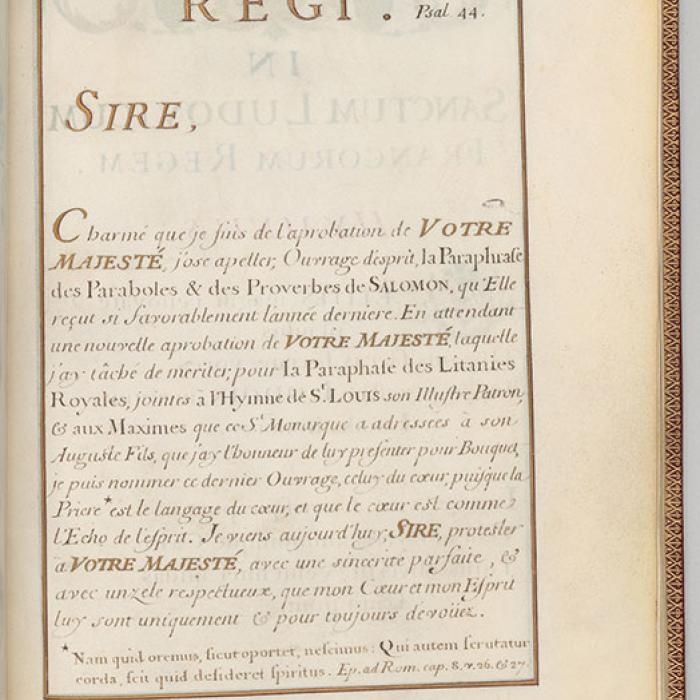

Royal Religion

The Bourbon line of the French monarchy began with Henri IV, Louis XIV’s grandfather, who was descended from the youngest son of Louis IX (St. Louis). The elaborate manuscript hymn honoring St. Louis at left—a presentation copy for Louis XIV—traces the familial connection to the saint and thereby underscores the Bourbons’ divine authority to rule.

At right is a volume of religious texts reissued annually for Holy Week (semaine sainte), the week before Easter. The engraved frontispiece

depicts Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska in prayer before a vision of the Christian Trinity. Such illustrations helped printers to market their yearly editions in a competitive market.

Written for Louis XIV (1638–1715)

Claude Charles Guyonnet, sieur de Vertron (1645–1715)

Hymne nouvelle a l’honneur de Saint Louis, ca. 1680

Manuscript on vellum

MA 23389

Women of the Court

Female book owners were a significant presence at Versailles, the French royal residence and seat of government during the reigns of Louis XIV, XV, and XVI. About one-third of the books in the Wrightsman collection bear the coats of arms of women, including queens, empresses, duchesses, and countesses.

A wife’s family armorial was traditionally paired with that of her husband, with his on the left and hers on the right. While his arms could stand alone, hers typically did not. The exceptions shown here, such as the armorials of Madame de Pompadour, Louis XV’s mistress and a prominent arts patron, and the Mesdames, three daughters of Louis XV, are rare examples of the independent status of certain women at court.

The books on display represent a variety of decorative styles and techniques, from the simple to the lavish, with armorials produced from either a single tool (or plaque) or built up from many small tool impressions. The books with more elaborate bindings were appropriate for display, while those with plainer covers—but decorated spines—were likely destined for bookcases. With the Wrightsman gift, nearly every royal woman at the French court in the eighteenth century is now represented by a signed document or bound book in the Morgan’s collection.

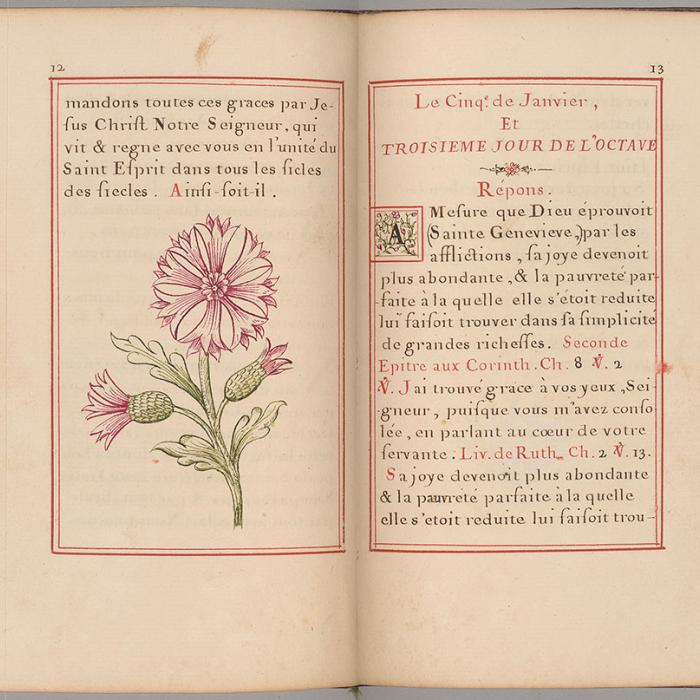

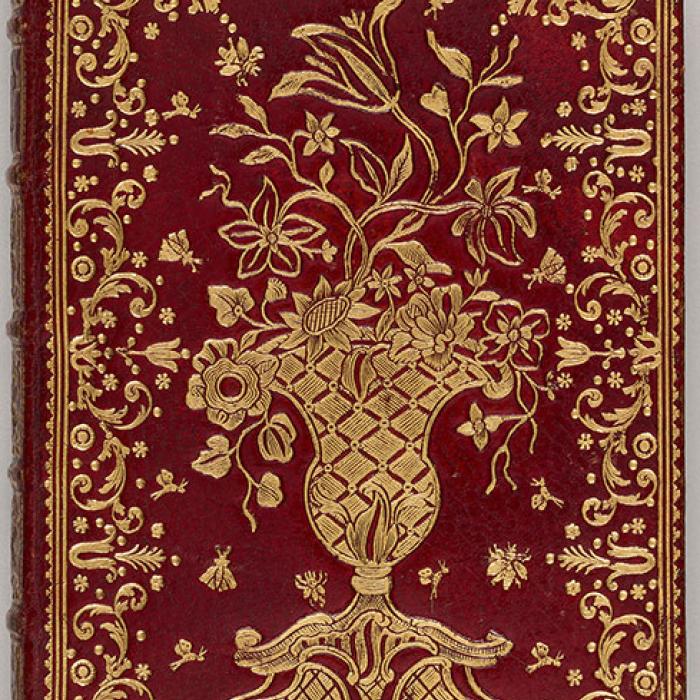

A Prayer Book for Élisabeth de France (1764–1794)

The small prayer book at the center of this case was used by Louis XVI’s younger sister Élisabeth in 1793, when the royal family was jailed in the Temple fortress prior to their executions by the republican government. It is signed inside “Elisabeth, La Temple, 1793,” with a small sketch of the Crucifixion. The text itself is dedicated to Marie Leszczyńska, and the book likely passed from her to her granddaughter Élisabeth. The elaborate binding is in keeping with the traditional degree of decoration on religious books. One large stamp produced the floral vase while many small tools, including several in the shape of butterflies and insects, were used for the surround.

Perhaps Pierre-Paul Dubuisson (act. 1746–62), binder

Dark red morocco, with gilt dentelle and vase-of-flowers motif, on: Heures nouvelles, 1759

Bequest of Julia P. Wightman, 1995; PML 125711

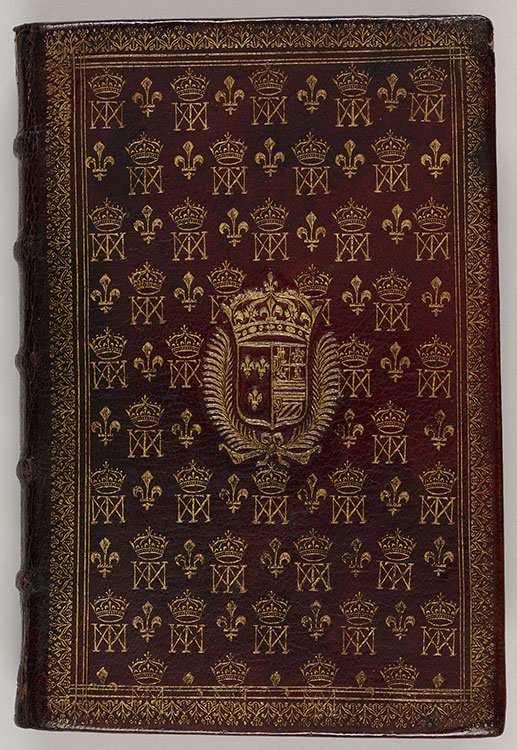

Madame de Maintenon and Françoise-Marie de Bourbon

Before she became Louis XIV’s second wife, Madame de Maintenon was the governess to his illegitimate children, including Françoise-Marie de Bourbon. At left is a

prayer book dedicated to the devout Maintenon. Although the text looks handwritten, it was in fact printed from engraved plates in a style meant to imitate

longhand. The decoration in Françoise-Marie’s manuscript prayer book at right emulates that in her governess’s book. When Françoise-Marie married her cousin

Philippe II, duc d’Orléans—who was regent of France during Louis XV’s minority—she briefly became the highest-ranking woman at court.

Written and bound for Françoise-Marie de Bourbon (1677–1749)

Phillipe Charles Gallonde (1710–1787)

Prières à Sainte Geneviève, 1743

Manuscript on paper

MA 23396

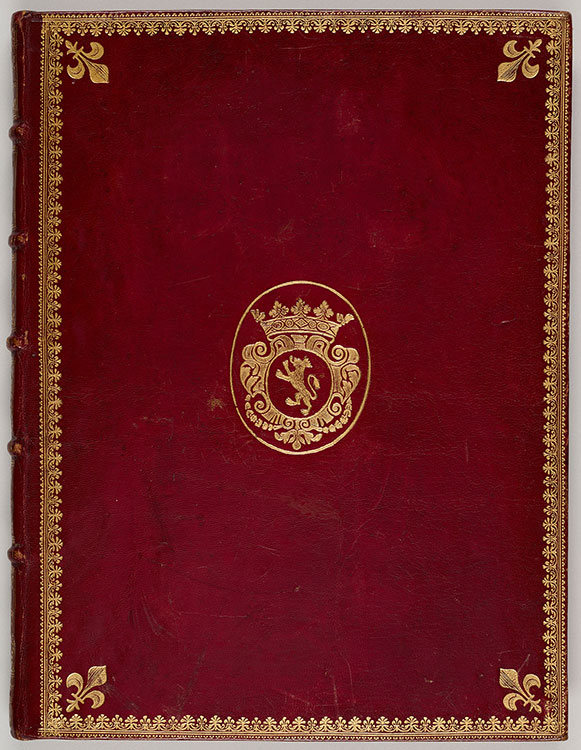

Marie-Adélaïde and Marie Leszczyńska

The two bindings at left in this case belonged to Marie-Adélaïde de Savoie and Marie Leszczyńska, respectively the mother and wife of Louis XV. Marie-Adélaïde’s

entire armorial composition (everything inside the oval) was produced from one large stamp, an unusual choice for the period that suggests there was a need to

efficiently decorate a large quantity of books. In contrast, the armorial and full cover composition for Marie Leszczyńska were built up from small individual

tools, which would have been laborious both to design and to implement—befitting her status as queen.

Bound for Queen Marie Leszczyńska (1703–1768)

Red morocco, with gilt dentelle and armorial, on: Jean Jacques Le Franc de Pompignan (1709–1784)

Poésies sacrées et philosophiques, tirées des livres saints, 1763

PML 198437

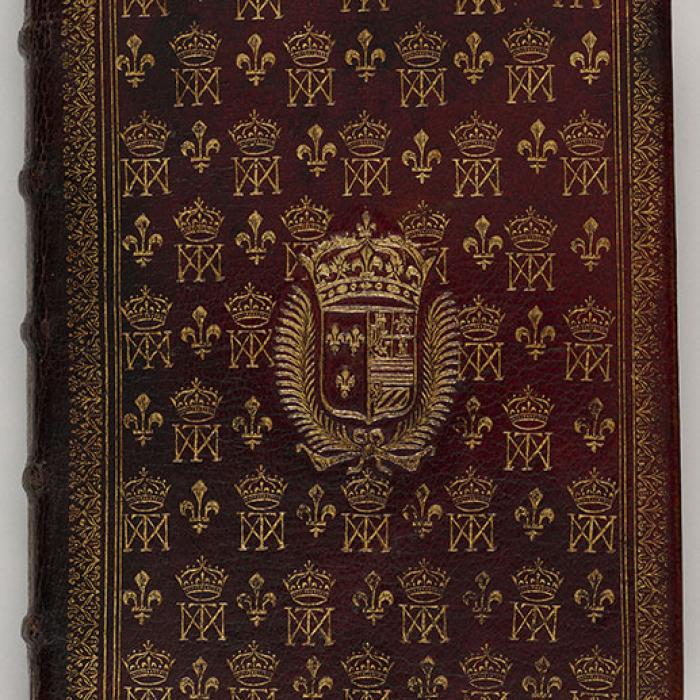

The Queen, The Wife, and the Mistress

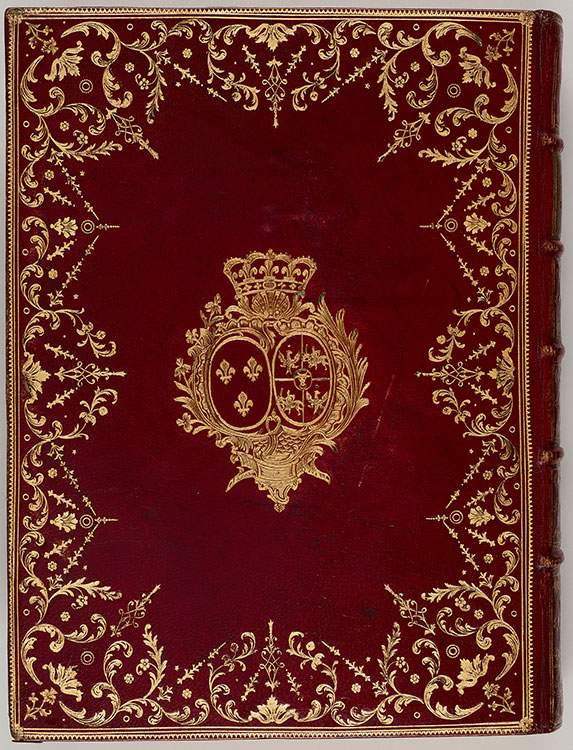

The binding at left for Marie-Thérèse, the first wife of Louis XIV, features a grid (semis) of fleurs-de-lis and her crowned MT cypher. Toward the end of the seventeenth century, binding decoration changed to focus on framing patterns with a centerpiece or armorial, as seen in the middle binding for Louis’s second wife, Madame de Maintenon. As an untitled queen of France, she was not permitted to use the French insignia as Marie-Thérèse did; however, this allowed Maintenon’s armorial to stand alone, undefined by that of her husband. Similarly, Louis’s mistress Madame de Montespan could not use the French royal emblems, and her binding at right includes only her initials.

:

Bound for Queen Marie-Thérèse (1638–1683)

Red morocco, with semis gilt tooling and armorial, on: Office de la semaine sainte, 1659

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan by 1906; PML 1884

Bound for Françoise d’Aubigné, marquise de Maintenon (1635–1719)

Augustin Du Seuil (1673–1746), binder

Red morocco, with gilt armorial, on: Guillaume Dardenne (act. 1737)

Description du plan en relief de l’Abbaye de la Trappe, 1708; PML 198439

Montespan and Maintenon

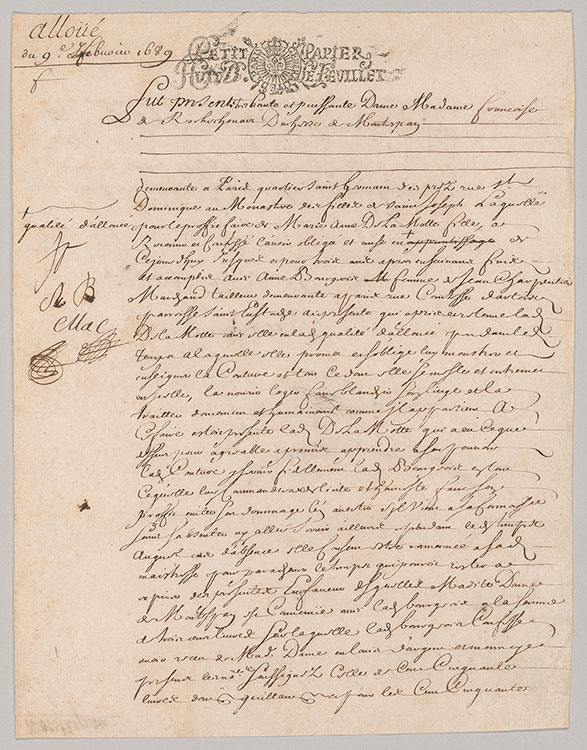

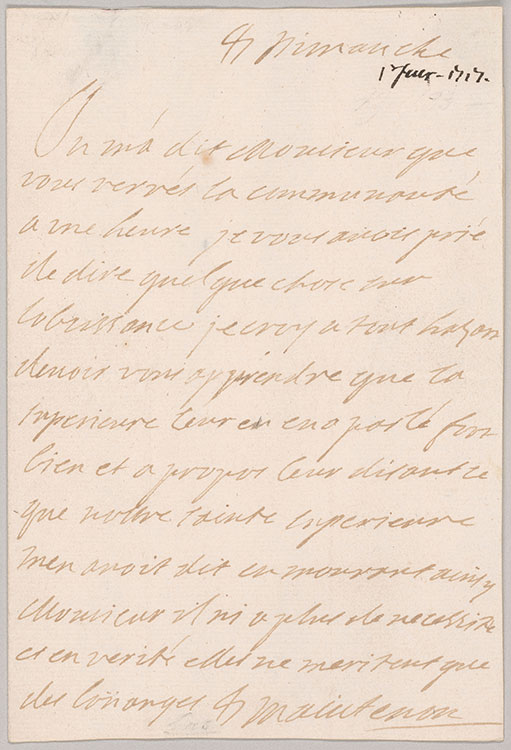

Prior to her 2019 bequest, Jayne Wrightsman gave the Morgan a group of forty-one letters and documents that provide a record of French court life from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. Over two-thirds of the documents were written or signed by women, including two queens of France, Marie Leszczyńska and Marie-Antoinette; Josephine, empress of France; Henrietta Maria, queen of England; Maria Theresa, empress of Austria; Catherine the Great, empress of Russia; and Madame de Pompadour, one of the most renowned courtiers of the ancien régime. The pair of documents shown here are signed by two significant women during the reign of Louis XIV: his mistress Madame de Montespan (left) and his second wife, Madame de Maintenon (right).

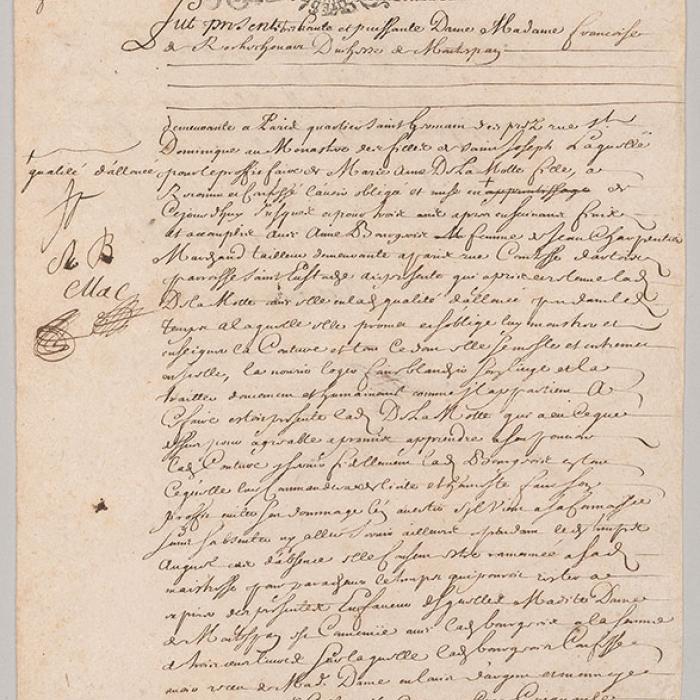

Françoise-Athénaïs de Rochechouart, marquise de Montespan (1641–1707)

Document authorizing the apprenticeship of Marie-Anne de la Motte to a tailor

Convent of St. Joseph, Paris, 9 February 1689

Françoise d’Aubigné, marquise de Maintenon (1635–1719)

Letter to Charles-François des Montiers de Mérinville (1682–1746), bishop of Chartres, place unknown, 1 June 1717

Gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1993; MA 4801 (27) and (22)

Pompadour's Library

Madame de Pompadour’s library contained over thirty-five thousand books, making it one of the largest literary repositories of the ancien régime. Her affinity for high-end works of art and luxury items extended to her books, many of which were lavishly decorated. On this binding, Douceur added red accents at the corners and within individual flowers to highlight the dentelle. Among Pompadour and her peers, books were often displayed with prominence as objets d’art—as Jayne Wrightsman lived with them—of which this colored and delicately gilt binding is an excellent example.

Bound for Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, marquise de Pompadour (1721–1764)

Louis Douceur (d. 1769), binder

Dark green morocco, with red morocco mosaic inlays, and gilt dentelle and armorial, on: Charles-Jean-François Hénault (1685–1770) Chronologique de l’histoire de France, 1752

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1910; PML 17282

Pompadour's Rodogune

Madame de Pompadour commissioned Boucher to illustrate the edition of Pierre Corneille’s play Rodogune, first published in 1647, that she was having printed at Versailles (on view in the case below). The frontispiece illustrates the climax of the play, when both Cleopatra, queen of Syria, and Rodogune, a Parthian princess, accuse each other of the murder of Seleucus. Boucher drew the scene from two vantages, which were later combined into a single composition. The original engraving, seen in the proof print to the right, was produced by Pompadour and then touched up for the final printing by Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger.

François Boucher (1703–1770)

Rodogune (Act V, Scene IV), ca. 1758–59

Black and white chalk on blue-gray paper

Purchased in 1927; III, 104a

Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, marquise de Pompadour (1721–1764), engraver, after François Boucher (1703–1770)

Proof impression of frontispiece for Rodogune, ca. 1758–59

Etching

Gift of Walter and Nesta Spink in honor of Charles Ryskamp; 2000.58

Mesdames De France

Adélaïde, Victoire, and Sophie were daughters of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska. The sisters held significant positions at court; Adélaïde, for example, served as an advisor both to her father and to her nephew Louis XVI. The bindings of the Mesdames are differentiated by color: Adélaïde’s are bound in red morocco, Victoire’s in green, and Sophie’s in yellow (citron). The diamond-shaped armorial of the fille de France (daughter of France) is the same for each, however. Of the three sisters, Adélaïde had the most extensive library—over eleven thousand volumes, surpassed only by the collection of Madame de Pompadour. Adélaïde’s books are richly decorated, demonstrating nearly every stylistic technique practiced by contemporary binders.

Bound for Madame Adélaïde (1732–1800)

Pierre-Paul Dubuisson (act. 1746–62), binder

Red morocco, with gilt plaque border, and painted armorial under mica, on: Almanach royal, 1757

PML 198427

Bookbinding Video

Frank Trujillo, Drue Heinz Book Conservator, and Lydia Aikenhead, Pine Tree Foundation Fellow, demonstrate gilt tooling on leather at the Morgan Library & Museum, 2021. Film produced by SandenWolff in collaboration with the Morgan’s Communications and Marketing Department. © The Morgan Library & Museum.

Decorative Tools

Finishing tools encompass an array of shapes and sizes. Made of brass or bronze, tools can be cut from a metal sheet with files and chisels or cast in a metal mold. When used, the tool is heated and then impressed on a binding, either directly on the leather (a blind finishing) or over gold leaf. A wooden handle protects the finisher’s hands from the heat of the tool and provides leverage. Some tools take the form of rolls and can be wheeled over the surface of a binding; others are stamp-like blocks that need to be impressed repeatedly. A pallet has a flared, fishtail-shaped tip that is used on a book’s spine or back.

On display is a decorative roll with a long handle used for a continuous border design; an ornamental tool for repeated single use; a curved pallet; and a center tool used on the corners and center of covers, and on spines. The example book cover is finished blind and with gold leaf. The video at right shows how these tools are used.