Tradition, Innovation, and Response: Stage Designs from the Morgan’s Collection

Designing a set for the theater stage presents a unique challenge: How does the artist visually transport live performers into the fictional world of the performance? Relying on a newly understood system of linear perspective, Italian Renaissance set designers created the illusion of a three-dimensional space projecting beyond the backdrop and receding toward a fixed point on the horizon, producing a window onto a symmetrical world in which the narrative unfolds. Later scenographers continued to employ this perspectival system, though they produced increasingly elaborate designs and special effects.

From the late seventeenth through the eighteenth century, the Bibiena family pioneered and popularized a different solution. As showcased in Architecture, Theater, and Fantasy: Bibiena Drawings from the Jules Fisher Collection, the family’s innovation was the scena per angolo, or “scene viewed at an angle,” which used multiple vanishing points beyond either wing of the stage. This development created the potential for seemingly boundless architecture.

The Bibienas were followed by later scenographic families, such as the Quaglios and Galliaris, who similarly worked across Europe for generations. The works shown here, offering a brief overview of European stage design from the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, pull from the Morgan’s immense collection of theater drawings.

Filippo Juvarra (1678–1736), Hall in a Royal Palace, ca. 1708–14. Pen and brown ink, with brown wash, over graphite; 203 x 266 mm. Bequest of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager.

Overview

After Bartolommeo Neroni, called il Riccio

Exemplifying Renaissance stage design practice, this orderly and symmetrical view of an idealized street recedes toward a single fixed point in the distance. This drawing copies Neroni’s original design for the comedy L’Ortensio, written and staged by the Sienese Accademia degli Intronati in 1561 to celebrate a visit from the city’s new ruler, Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici. The architectural enclosure featuring allegorical figures in niches is the earliest-known depiction of a proscenium arch, the frame through which the audience views the stage. Around 1589, Neroni’s influential design circulated as a woodcut reproduction by Andrea Andreani. The Morgan’s drawing dates from this moment, attesting to the enduring interest in Neroni’s design decades after its conception.

After Bartolommeo Neroni, called il Riccio (ca. 1505–1571)

Stage Design, from L’Ortensio (1561), ca. 1589

Pen and brown ink, with brown wash

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1982.75:438

Attributed to Giulio Parigi

This impressive drawing depicts the gaping jaws of a bestial monster—the anthropomorphized portal into hell, where demons and fantastical creatures cavort among the flames. A popular iconography during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the hell mouth was a regular feature on the stage, especially in dramatizations of Christian narratives like the Harrowing of Hell and the Last Judgment. This seventeenth-century set, however, probably accompanied one of the increasingly popular stagings of mythological narratives in which a protagonist descended into the underworld. The visual language of this apocalyptic inferno recalls the stage designs of Giulio Parigi, an influential festival designer at the Medici court in Florence.

Attributed to Giulio Parigi (1571–1635)

A Hell Mouth, ca. 1620

Pen and brown and black ink, with gray wash, over traces of black chalk

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1982.75:451

Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini

As opera swept across the Continent in the seventeenth century, European courts began importing Italian musicians and scenographers. By 1651, Lodovico Burnacini had moved from northern Italy to Vienna to assist his father, Giovanni (1610¬–1655), theatrical engineer to Leopold I, the Holy Roman emperor. In addition to opera, the imperial court was partial to sacred productions, staged in ecclesiastical settings with theatrical backdrops like the one seen here. This depiction of a biblical scene relates to a series of twenty similarly conceived drawings by Lodovico, which may have been made for such productions.

Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini (1636–1707)

Hagar and the Angel, ca. 1680

Pen and brown ink, with gray wash, over black chalk

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1982.75:172

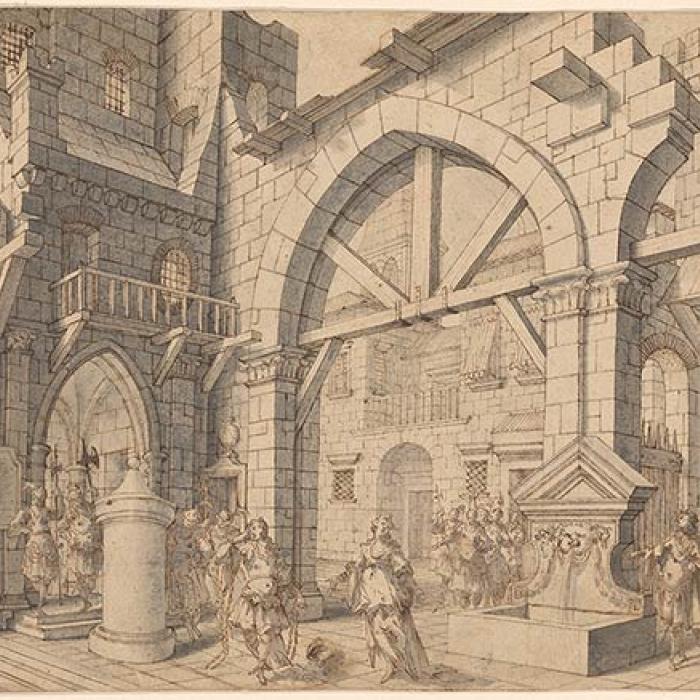

Giacomo Torelli

The resplendent King Louis XIV enters a magnificent atrium at left; a Roman procession leads his lion-drawn chariot. Behind them, a group of figures gathers around an altar. Attendees are packed among the ornate colonnades and peer down from the balconies of Torelli’s lavish architectural setting. Torelli arrived in Paris in 1645, bringing with him the grand stage sets that had made him a success in Venice. Starting in the mid-1650s, the young Sun King increasingly organized and performed in entertainments, particularly ballets, for which Torelli would design sets. This refined drawing cannot be linked to a specific production, however; it may simply show the king entering an otherwise unrecorded court festival.

Giacomo Torelli (1604–1678)

A Royal Entry into a Classical Court, ca. 1650–65

Pen and brown and black ink, brush and black ink, with gray wash

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1982.75:636

Filippo Juvarra

A contemporary to the Bibienas, Juvarra led a successful career as an architect and scenographer, working throughout Italy as well as in Spain and Portugal. The stage design shown here, with the wings of the courtyard set at an angle, echoes the Bibienas’ innovations. The drawing style, however, is Juvarra’s own. The spirited pen work communicates energy, and his accomplished application of wash describes the dramatic play of light across the hall’s surfaces.

Filippo Juvarra (1678–1736)

Hall in a Royal Palace, ca. 1708–14

Pen and brown ink, with brown wash, over graphite

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1996.75:19

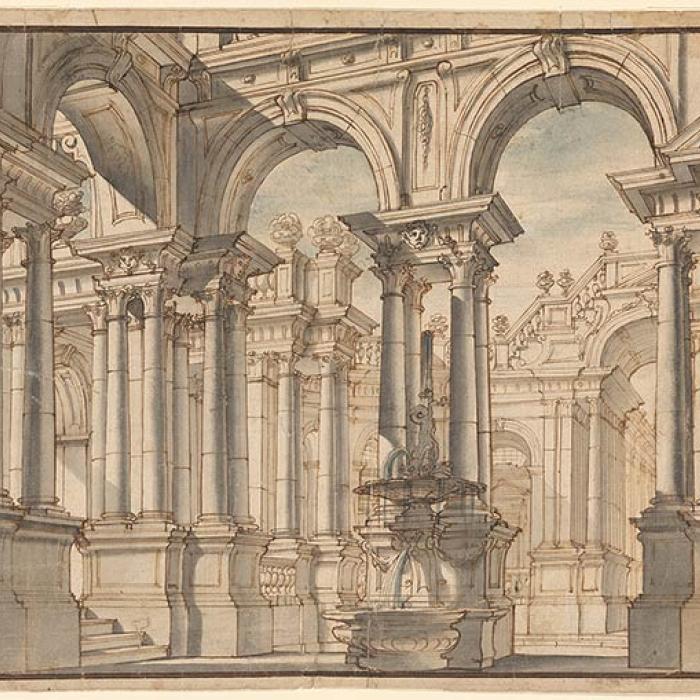

Attributed to Giuseppe Galli Bibiena

This drawing of a luminous courtyard is an example of the Bibienas’ signature innovation, the scena per angolo, or “scene viewed at an angle.” The intersecting axes open outward, expanding beyond the sheet’s margins and inviting viewers to imagine the full breadth of the immense architecture. The attribution of drawings within the Bibiena workshop is a famously difficult problem, for the family members trained each other and numerous assistants, even cultivating a common “Bibiena style.” Formerly assigned to Ferdinando (1657–1743), this drawing is now generally believed to be by his son Giuseppe.

Attributed to Giuseppe Galli Bibiena (1695–1757)

A Cortile, ca. 1715–30

Pen and brown ink, with gray wash and blue watercolor, over graphite

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1982.75:126

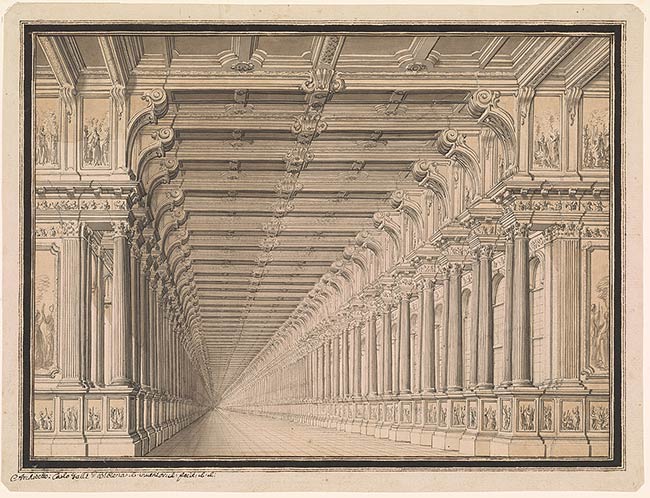

Carlo Galli Bibiena

Highly finished and minutely detailed, Interior of a Gallery was meant not for the stage but as an autonomous work for display. Earlier designs with single-point perspective interrupt the eventual convergence of lines by placing a structure in front of the vanishing point. Here, Carlo allows the lines to meet, representing a fantastical, infinite interior within the confines of the image. The artist’s exacting description of the ever-shrinking columns creates an endless and mesmerizing recursion.

Carlo Galli Bibiena (1721–1787)

Interior of a Gallery, ca. 1755–65

Pen and black ink, with gray and brown wash, over black chalk

Thaw Collection; 2017.5

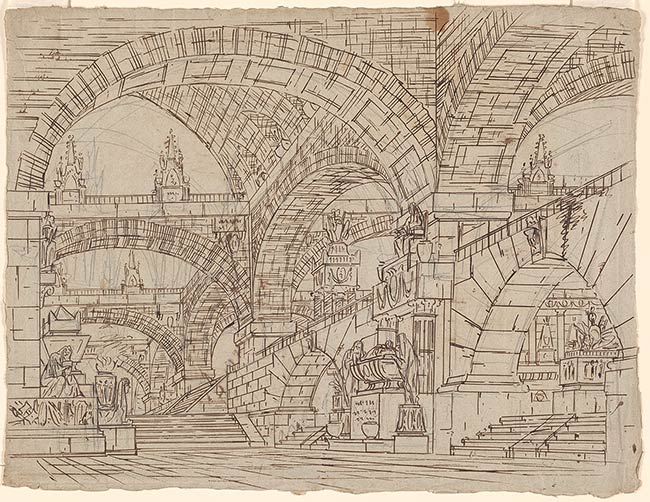

Attributed to Francesco Galli Bibiena

In this characteristic example of the Bibienas’ scena per angolo, the grid of paving stones and the angled brick walls emphasize the orthogonal systems with which Francesco organized the towering prison. The extended and layered space encourages the viewer to envision peering around the corners into implied but unseen spaces. Prisons were frequent settings for eighteenth-century plays, but painted backdrops rarely included figures; this drawing is perhaps a record of a performance, or it could have been a stand-alone drawing meant to showcase the Bibienas’ design principles.

Attributed to Francesco Galli Bibiena (1659–1739)

Prison Courtyard with Figures, ca. 1720

Pen and brown ink, with gray wash, over graphite

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1982.75:111

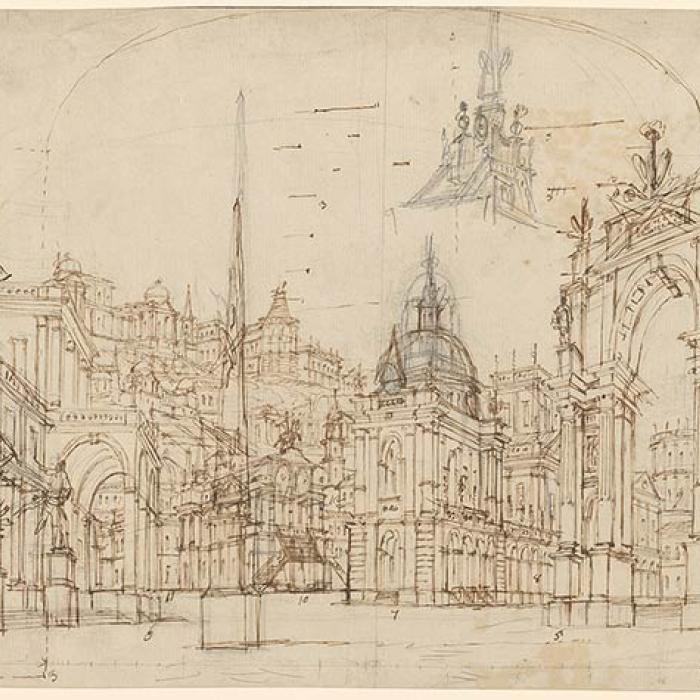

Lorenzo Quaglio I

In this working drawing, Quaglio sketched an elevation of a city square and added a rough ground plan of the theater stage, seen from above, at the top of the sheet. The artist’s numerical annotations give a sense of how the painted flats would have been positioned on the stage. Along the lower margin, Quaglio made ruled measurements that would have helped him devise the scene for the stage’s dimensions; the measurements also would have facilitated his transferring the design to a more polished drawing (now in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence) and, ultimately, to a painted set.

Lorenzo Quaglio I (1730–1804)

A City Square with Buildings on a Hill in the Background, ca. 1760–70

Pen and brown ink, over graphite

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1982.75:523

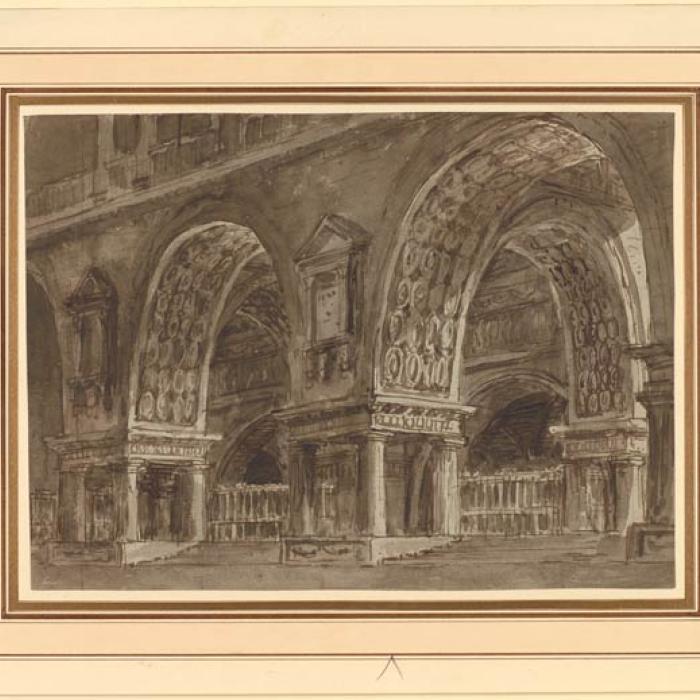

Gaspare Galliari

Galliari rendered this monumental, imposing loggia with a loosely handled pen, enveloping the scene in shadow by means of his liberally applied wash. The date and title of this drawing are based on a reproduction by Luigi Rados (1773–1840), who published a series of aquatints after Galliari’s designs in Milan in 1803. The inscription on Rados’s print gives the title of Logge terrene (ground-floor loggias), but it is unclear whether this original design was for the stage set of a specific production.

Gaspare Galliari (1761–1823)

Logge terrene, ca. 1803

Pen and brown ink, with gray wash, over graphite

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1982.75:275

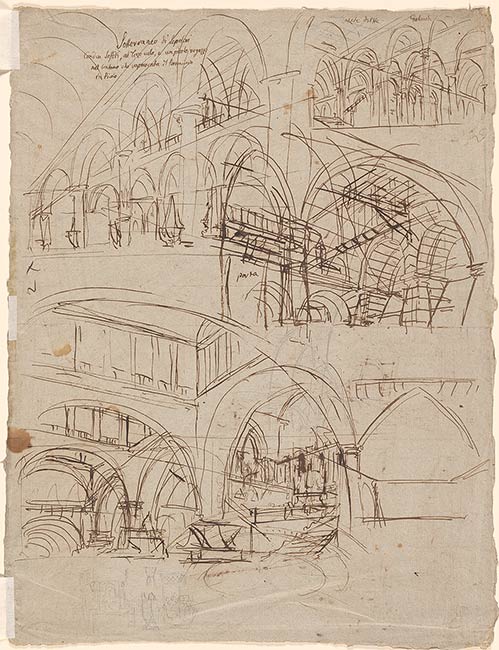

Lorenzo Sacchetti

Born in Padua, Sacchetti began his career in Venice before relocating to Vienna in 1794, and from 1817 he was mainly active in Prague. His work represents the continued exploration of the Bibienas’ pioneering visual language even into the nineteenth century. The fluidly executed Vaulted Funeral Hall conveys the freedom with which the artist developed this immense architectural space. Indeed, in 1830 Sacchetti published a treatise titled Quanto sia facile l’inventare decorazioni teatrali (How easy it is to invent theatrical decorations), printed in both Italian and German.

Lorenzo Sacchetti (1759–1836)

A Vaulted Funeral Hall, ca. 1810

Pen and brown ink, over graphite

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1982.75:567

Antonio de Pian

De Pian’s small drawing of a massive hall offers a striking contrast, setting his exacting linework and controlled gray wash against the hastily applied red, blue, and yellow watercolor. These bold primary colors aside, the careful execution, framing line, and signature suggest that De Pian produced this drawing as an end in itself—a demonstration of his abilities as a scenic designer. Such displays circulated during the artist’s lifetime, most notably through a bound series of reproductions of his sets, engraved and published by his contemporary and fellow Viennese stage designer Norbert Bittner in 1818.

Antonio de Pian (1784–1851)

A Massive Vaulted Hall, ca. 1815–30

Pen and brown ink, with gray wash and opaque watercolor, over graphite

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager; 1982.75:662