Settling in New York

In 1997, as opportunities to show her work in New York expanded, Sikander decided to move there. She embarked on more ambitious installations of layered tracing-paper drawings, wall drawings, and projects combining the two. The speed and looseness of these large-scale works contrasted with the increasing refinement of her paintings. During a residency at Artpace, San Antonio, in 2001, she created her first animation.

In response to life in New York, Sikander continued to focus on female multiplicity and agency while also developing fresh concepts, especially after the events of 9/11, which affected her work deeply. “Questions of wealth and class, trade, global economics, race, and capitalism all started to percolate,” she said. “Negotiating a sense of belonging during this phase was riveting.”

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

The Many Faces of Islam

This piece was created for the New York Times Magazine feature “Old Eyes and the New: Scenes from the Millennium, Reimagined by Living Artists,” and was published in the September 1999 issue. The two central figures hold between them a piece of American currency inscribed with a quote from the Quran: “Which, then, of your Lord’s blessing do you both deny?” The surrounding figures speak to the shifting global alliances between Muslim leaders and American empire and capital. According to Sikander, “The 1990s was about war, coalitions, alternating friends and foes, imposed sanctions, debts forgiven, and human rights brushed under the carpet as America flexed its military muscle around the world. This work took this history into account, and I proposed that American policy in Islamic countries would become a defining issue in the new millennium.”

The portraits are, clockwise from upper left: Anwar Sadat; Menachem Begin; Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Pakistani singer of Sufi devotional music; Muhammad Ali Jinnah, founder of Pakistan; Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, president of Pakistan; Benazir Bhutto, prime minister of Pakistan; Malcolm X; Salman Rushdie; Nawal el Saadawi, feminist writer and physician, spokeswoman for the status of women in the Arab world; King Hussein; King Faisal; Asma Jahangir, Pakistani human rights lawyer and social activist; Hanan Ashrawi, spokeswoman for the Palestinian nation; Ayatollah Khomeini; Saddam Hussein.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

The Many Faces of Islam, 1999

Gouache, watercolor, gold leaf, and graphite, on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

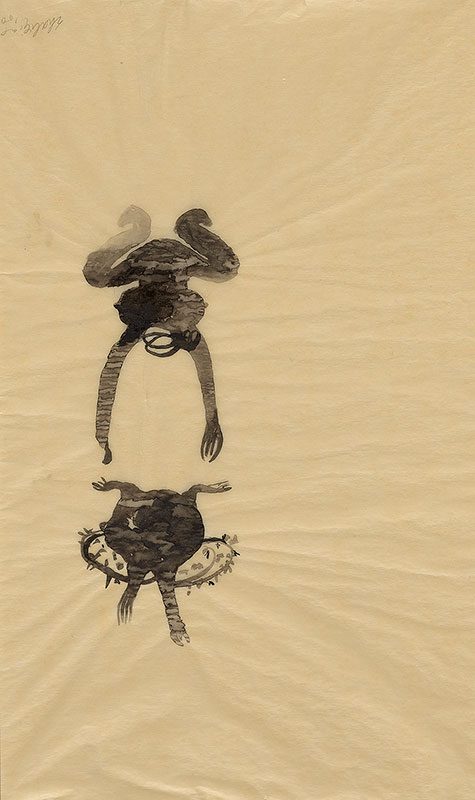

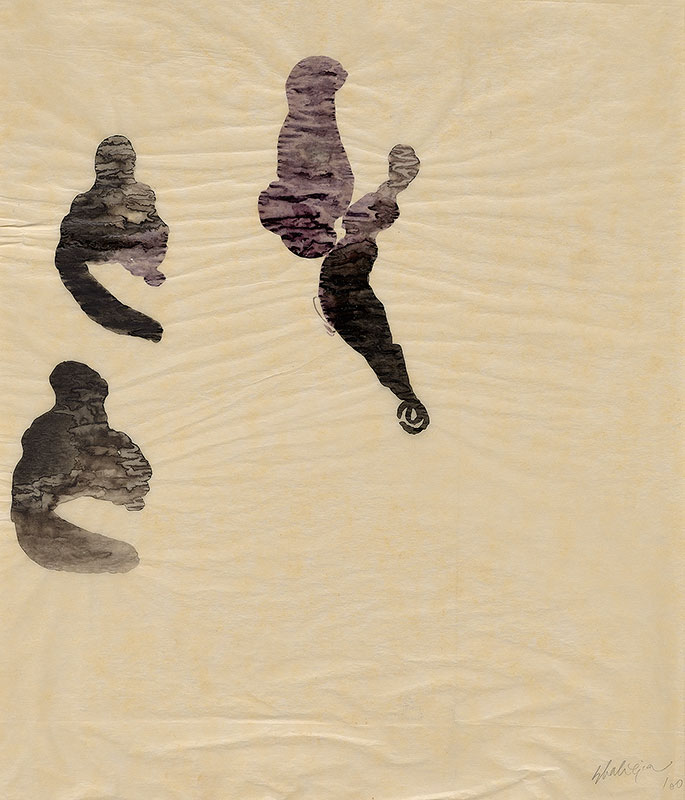

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation II

This repertoire of forms and figures emerged during a period when Sikander was creating fifty to one hundred fast, gestural ink drawings each week. Suggestive forms were later given definition and supplied with appendages, typically using a marker pen. The resulting characters—often female, sometimes androgynous, sometimes monstrous—repeatedly enter her work, frequently as a collection of alter egos. According to Sikander, the figures address “the lack of female artists represented in art history and the art world and the misogyny women encounter in almost all spheres of work and life. The act of drawing became about converting erasure into opportunity through wit and candor.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation II, 1994/95

Ink on sketchbook pages

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: This is a time when I was reading and re-reading many texts by authors such as bell hooks, Audre Lorde, Angela Carter, Fahmida Riaz, Parveen Shakir, expanding my grasp of female poets and feminist forms, and in turn, exploring language from specific points in places of women's narratives. I was really keen to develop a lexicon of forms that could be both inventive and witty and could open up stories around gender and sexuality, forms that would sort of emerge from within, almost as if I had regurgitated them after perusing classical and historical South Asian sculptures and paintings. So for me, this process of locating a relationship to tradition was not to mimic, but to find a language that was connected to the research that I was doing, connected in a very natural manner. So I was kind of asking, "What is originality? How does one create something new?" The world is full of mysteries. There's always going to be a variety of distances between the real and the imagined. So I'm interested in history, I'm interested in politics, but I'm also interested in the dynamism of form, form as something alive and in conversation with its time, space, and language.

Mind Games

This scene is a restaging of the painting Jahangir Receives Prince Khurram from the imperial Mughal manuscript Padshahnama (Book of emperors), now in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Using the durbar hall as a compositional device, Sikander centers two self-portraits flanking a subway map, with rooftop water tanks in the top margin further signaling a New York City setting. In the lower register, courtiers from the historical painting—now wearing masks—gather, perhaps as witnesses of the past. Presiding at center is the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Sikander sees this deity as nonbinary and a symbol of multitude, with the ability to look in all directions and possess any form. She was intrigued with these chameleonlike powers and with masking as a metaphor for the many sides—some unseen—of any narrative.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Mind Games, 2000

Watercolor over inkjet print on tea-stained wasli paper

Courtesy of John McEnroe

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Riding the Ridden

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Riding the Ridden, 2000

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Niva Grill Angel

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Elusive Reality

Two female figures meet at the center of this work. The seated woman is inspired by Deccani painting traditions that originated in Central India in the 1500s. The overlaid, upside-down portrait is of Sharmila Desai, an Indian dancer with whom Sikander worked closely in New York. Desai sometimes performed in spaces installed with Sikander’s drawings. Sikander photographed the dances and then incorporated select postures into her paintings.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Elusive Reality, 1989–2000

Watercolor and collage on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, New York

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: Working with another South Asian female and developing a collaborative practice, which allowed me to work with her where she choreographed many of pieces and performed in the drawings that I made. And then I brought her back into these small paintings, that dialogue that started to emerge was almost the strengthening of a South Asian feminine identity. So this is a time when being Asian American or Asian anything, one was questioning that paradox of being invisible while standing out. And what that broad racial category meant where so many different nations, ethnicities, classes, cultures, communities, languages had to vie to be recognized. So this work embodies that early period of developing a kind of collective identity with other South Asian artists.

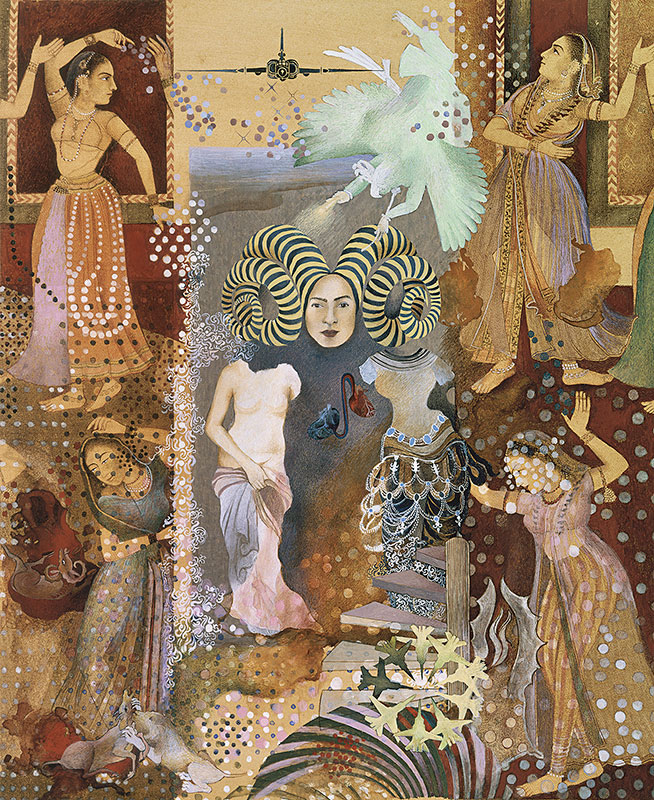

Pleasure Pillars

The array of archetypes portrayed here reveals the range of sources that Sikander looked to as she celebrated female sensuality and desire. Her central self-portrait with ram’s horns conjoins fragmented statues inspired by the Roman goddess Venus and a South and Southeast Asian celestial dancer. Above, two images of destruction threaten this scene of unrestrained pleasure: a fighter jet, which Sikander added in the aftermath of 9/11, and a winged, hybrid creature that seems to shoot fire from its hands.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Pleasure Pillars, 2001

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Amita and Purnendu Chatterjee

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: In this painting, there are multiple female references. So all these female avatars in my art have thoughts, emotions, feelings, and the iconographies are coming out of this vast intellectual virtuosic manuscript traditions of Central, South, and East Asia. There are a lot of syncretic layered visual histories that are usually referenced, and these women also embody a multidimensionality. And at times they may be androgynous, but they're complex and confident and proactive and also playful. That's what I wanted to celebrate in this particular work is the female sensuality, the desire as well as the courage. And it was a way of speaking back to the very fetishized female representations, especially at that time in 2001. I was countering the very paternalistic belief about saving of Muslim women from Islamic extremism, which was often used to justify the US imperial war and invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. So, this painting speaks back to some of that representation. You can see that the archetypes are gathered from multiple religious and cultural sources. There's this fighter jet under which even there's a portrait, which could be my self-portrait also.

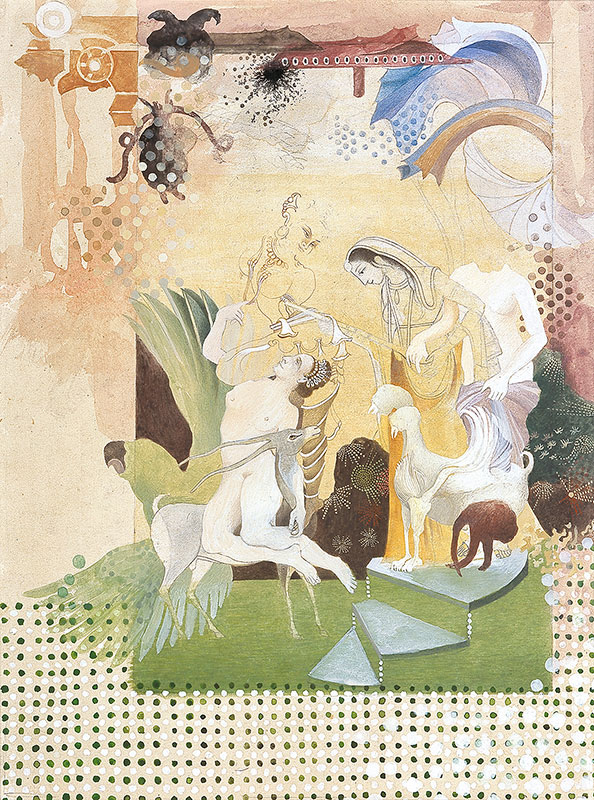

Sly Offering

The foundation for this work is Ascension of Solomon, a Safavid painting from the early 1500s now in the Freer Gallery in Washington, DC. Sikander disrupts the notion of sovereignty by removing King Solomon and handing the empty seat of power to her Indian and Greek female protagonists, who share or vie for control.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Sly Offering, 2001

Watercolor and inkjet outline on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Judy and Robert Mann

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: As in so much of my work here too, you can see the female protagonist rejecting the colonial, the male gaze. It is my intention to reimagine archetypal characters to tell richer stories. There's almost a back and forth a dialogue between historical paintings and languages, almost like an attempt to tell a story which operates very much like a poem, precise, as well as open-ended. I have a deep affinity with poetry as a catalyst, its ability to liven up language and to pack so much expression in a condensed form. When I look at this painting, I can read a bit of Adrienne Rich, I can read a bit of Solmaz Sharif in this work. And that's what I aim in my practice, is how to keep the work alive by adding many layers of meaning so that it can speak to multiple points of views. There's definitely a little bit of anarchy, a lack of sovereignty, and these constructions of femininity and beauty are all there as ways to dismantle perhaps orthodox representations. In this work, I think I was exploring what is a state of homelessness, not as in exiled or diasporic artist, but more as a collective female agency that could possibly rupture through abodes of patriarchy as well as militarism across national boundaries, cultures, and histories.

Intimacy

At center left in this work is an Indian celestial dancer modeled on a sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The dancer flirtatiously entwines herself around a figure taken from the sixteenth-century Italian Mannerist painting An Allegory with Venus and Cupid, by Agnolo Bronzino. Sikander created this pairing in response to Partha Mitter’s 1977 book Much Maligned Monsters: A History of European Reactions to Indian Art, which points to the role of cultural stereotypes in the European perception of Asia. At right is another pair of figures, sourced from Greco-Roman and Indo-Persian traditions. They stand arm in arm beside a two-headed creature, reinforcing multiplicity and suggesting the closeness and overlap of histories and cultures.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Intimacy, 2001

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Partial and pledged gift of Jeanne and Michael Klein, 2001

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

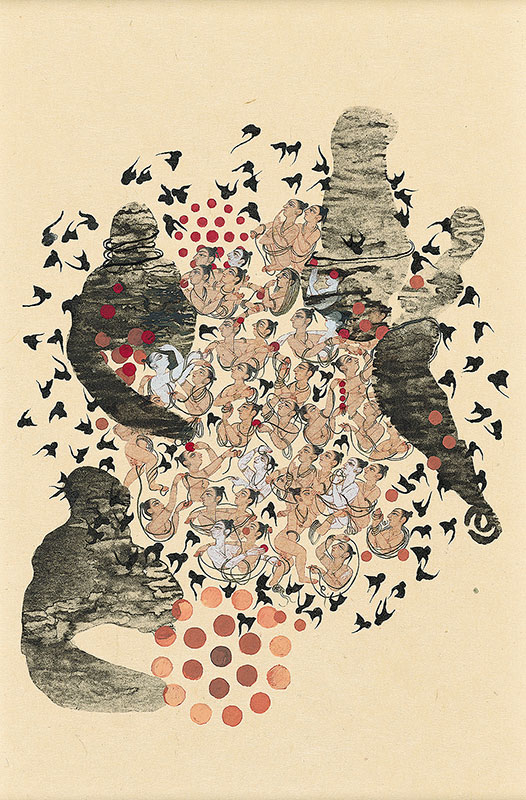

Gopi Crisis

The small female characters portrayed here derive from gopis, female cowherds and devotees of Krishna. Depicted from the waist up, they seem to be bathing, as they are often shown in Indian paintings. Large shadowy creatures—vaguely human, somewhat phallic— protect and contain the gopis, while bats or birds disperse from the center of the image. On close inspection, these flying forms are the hair of the gopis, detached and given life as a new symbol that will populate and animate Sikander’s work.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Gopi Crisis, 2001

Watercolor, gravure, inkjet, and chine collé, on tea-stained paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

From the series Monsters, Female Desires, and States of Dislocation

These uncanny forms interpret an array of objects, including swords, vessels, cannons, amulets, and masks—the types of images that might feature in Western coffee-table books on Islamic and Indian art. Sikander’s representations transform the inanimate objects into human-animal hybrids, imbuing them with agency. Her approach, she explains, was “an inventive and ironic play on the colonial histories of dispersing, rupturing, archiving, cataloguing, and institutionalizing art and artifacts of native cultures.” The distinct pattern created by the coagulation of ink on the sheets suggests reptile skin, ideal for rendering these subjects.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

From the series Monsters, Female Desires, and States of Dislocation, 2001

Ink on tracing paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Turmoil

This playful landscape scene features the female cowherds and devotees of Krishna known as gopis (also seen in several other paintings in the exhibition). Freed from previous restrictions, they seem ready to take on the world. At left are their scooters—not that they need them, as they seem capable of flying. They only have traffic signals to stop them.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Turmoil, 2001

Watercolor and inkjet on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Philip H. Isles

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

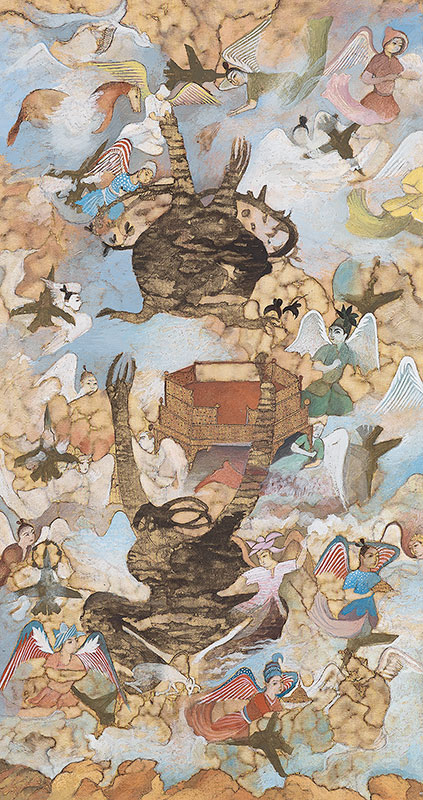

No Fly Zone

Sikander returned to the same Persian painting here that was the base for Sly Offering (on display nearby). Painted just as the United States was ramping up its response to the 9/11 attacks, No Fly Zone imbues the monstrous protagonists of Sikander’s early vocabulary with new political relevance. As scholar Sadia Abbas has noted, the empty throne in this painting—one of Sikander’s favorite motifs of the early 2000s—“marks a crisis of postcolonial sovereignty in an era of revived imperialism.” The jets and angels clad in red, white, and blue wings make clear the central role played by the United States.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

No Fly Zone, 2002

Watercolor, gravure, and inkjet outline, on wasli paper

Collection of Mitzi and Warren Eisenberg

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: In the center of this painting, you may recognize these ambiguous forms. If you look closely, they are evocative of the female body and they are anchoring the entire composition, even maybe disrupting a certain cosmic order of patriarchy, sovereignty. This work is a series that I did in the early 2000s when I was reflecting upon war, women and power, violence and capitalism, the drama of all these movements that are at the heart of a global crisis. There's also reference to many who are forced to migrate, the refugees, those from countries that are always on the no-fly list. As a Pakistani national, I was unable to travel outside of the US for more than eight years when my green card application was pending or lost in that abyss. So I was making also a statement on these questions of who controls power? How is that particular armature upheld? What is that space between the migrant and the immigrant, the citizen and the foreigner, how it's always in flux, a space where more and more communities are now defining that space on their own terms, and reflecting more of the complex, dynamic and evolving world that we all live in.

Web

The towers and aircraft in this painting call to mind the 9/11 attacks. The towers also suggest oil derricks, possible referencing the United States’ dependence on foreign oil, which was brought into question during President Bush’s impending invasion of Iraq. Heraldry links present-day policies to colonial- era exploitation. The large purse-like form is a lingam casket, which holds an amulet. The spiderweb is a reference to the one in a popular tale that shielded Muhammad from persecutors as he hid in a cave. The lush landscape with animals both nurtured and preyed on—copied from a Mughal manuscript painting—is the foundation of this composition filled with references to protection and destruction.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Web, 2002

Ink, gouache, gravure, and inkjet outlines, on tea-stained wasli paper

RISD Museum: Paula and Leonard Granoff Fund 2003.46

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Running on Empty

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Running on Empty, 2002

Watercolor and inkjet on wasli paper

Collection of Anika Rahman

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Segments of Desire Go Wandering Off

At the center of this painting, a multiarmed, uprooted female tries to hold on to all she desires—a chalawa (symbolizing impermanence), a turtle (symbolizing endurance), a floating child, a portrait of a woman, and a self-portrait of the artist. Sikander painted this figure over a large portrait of a trickster drawn by the Houston-based artist David McGee. All of the faces have been partly obscured, keeping racial and cultural identities shifting. As an immigrant, Sikander was questioning the prevalence of hyphenated identities in America and who is recognized as a citizen.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Segments of Desire Go Wandering Off, 1998

Collage with watercolor and graphite, on teastained wasli paper

Collection of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

The Pink Pavilion

Returning to a technique she first developed at RISD, Sikander created many multipart works, such as this one, on paper coated with a combination of clay, gesso, acrylic, and patching compound. More stable than tracing paper, this surface allowed her to precisely delineate the forms. Varying the amount of red clay provided a color range that Sikander likened to flesh tones. This textured, absorbent surface coaxed new characters and narratives from Sikander’s imagination. Tumbling, floating, and flying, the interacting figures are engaged in exuberant movement.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

The Pink Pavilion, 2002

Ink, opaque watercolor, and watercolor, on clay-coated paper

Collection of Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, New York

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: In my practice, drawing has a very central role. Drawing implies movement across time, across formats, across mediums. Drawing is a means of imagining and bringing ideas to life. So this series is a constellation of ideas. I see it as big ideas in small spaces, like a glimpse through the pages of a sketchbook. Many of the images seem to be in a joust, almost like a battle over each other. There's movement, both literal and symbolic, as in the crossovers between man and nature, human and animal, plant and animal, geometry and bodies, male and female. I don't see any particular beginning or an end in this work. You can start with any section, move left or right, up or down. Movement can be both literal as in the physical crossing of geographical borders, whether it's bodies, commodities, resources. But movement can also be symbolic, and that is the sense of belonging as where do you belong or what are you being excluded from? So that's a little bit of what this work is, that representations are not static.

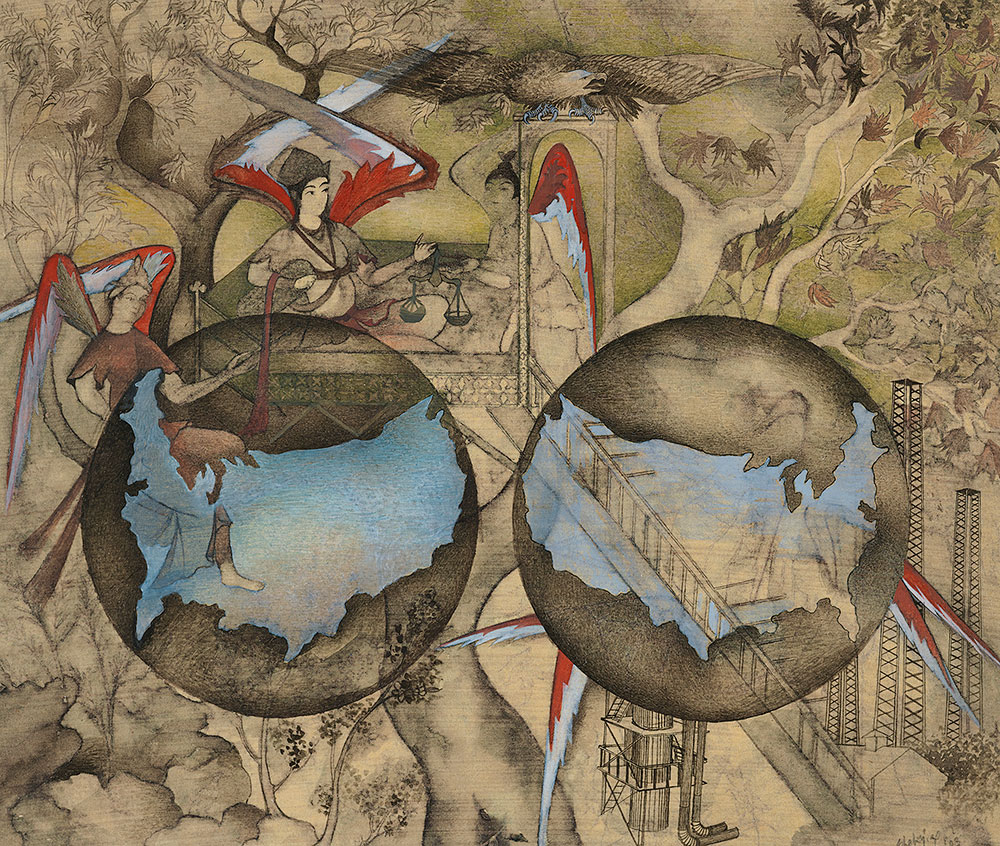

United World Corp

A detail from A Garden of Heavenly Creatures, a sixteenth-century Safavid painting in the Freer Gallery of Art collection, forms the backdrop for this work. In Sikander’s intervention, the garden has been overrun with an American presence. Globes featuring maps of the United States appear at center, an eagle reigns at top, and the angels have red, white, and blue wings.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

United World Corp, 2003

Watercolor and inkjet on wasli paper

Collection of Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, New York

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

SpiNN (III)

This painting, created for the animation SpiNN, includes several scenes of gopis in an act of rebellion. The gopis join together to create the beast that Krishna rides into the durbar hall. Once inside, they take over the space. Traditional Indian manuscript paintings typically feature only a single prominent gopi, Radha, the favored consort of Krishna. As Sikander multiplies the gopis’ numbers, she gives them all the agency of Radha, speaking to the power of a collective feminine space.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

SpiNN (III), 2003

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Promised gift of Jeanne and Michael Klein in honor of Annette DiMeo Carlozzi, 2015

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: I started experimenting with animation in 2000. And it came very naturally to me in my process because I was always building layers in my paintings to create density and transparency. And sometimes there are more than 10 layers added into a single detailed small painting. So with that in mind, I thought I would register and document or scan every other layer of the painting as I built it. And that's where SpiNN emerges from, is it's in dialogue, in relationship to its painting, the counterpoint. And one of the most interesting shifts that happened in this work was when I painted the bodies of the female and then chose to eliminate them. But I wanted to retain some of their references in the work. So as they gather, their hair disassociates from their bodies. And that little element is small enough that it started to operate as a particle system. And I ran with that idea. So eventually, so much of the later animations are built up with the particle system in mind. And here you see the hair function almost like swarms or birds or bats or insects. And it can oscillate between a singular element, which is almost like the DNA of the feminine body. But then in its multiplication, it can also conjure up multiple different associations.

Epistrophe

In the late 1990s, the 2000s, and occasionally since, Sikander created installations of layered tracing-paper drawings, most often in combination with wall drawings, as a counterpoint to her painting practice. The intention was to use fluid, spontaneous gestures that involved her whole body and amplified her invented motifs. This large-scale work requires a different kind of labor, skill, and pace than her smaller, intricate compositions, but she still sees it as in dialogue with classical traditions. Sikander is also attracted to the openness of the piece: “There is no intention to hide anything,” she explains. “Everything is very visible; the paper is very transparent. It flows, it moves. All marks, including any flaws, become a part of the piece, which has no borders and can expand in any direction, marking a site that is unstable and multivalent.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Epistrophe, 2021

Gouache and ink on tracing paper

Collection the artist

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

Promiscuous Intimacies

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Promiscuous Intimacies, 2020

Patinated bronze

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: The two protagonists that you see in this sculpture are actually in my other paintings also, especially Pleasure Pillars and Intimacy. So you can recognize them there, but I wanted to call them out of the paintings and develop them into sculptures to see what would happen when these female bodies bear the symbolic weight of communal identities from across multiple temporal and geographic terrains. So I first sketched out these female characters in 2000 for a banner for MoMA when I worked with the curator, Fereshteh Daftari. At that time, I was just interested in art histories, classicism, and ethnocentric reactions to Indian art. But I was also making a point by entangling mannerism, the anti-classical impulse within the Western tradition alongside Indian art, both as accomplice witnesses of a one-sided history. But in 2017, I had the opportunity to be part of the New York City Mayor's Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers. And during that process, when I was hearing differing public opinions around public monuments, the complicated histories, a sort of a historical reckoning, and these tensions between communities regarding representation, at that time I felt that if I ever make a sculpture, I would make an anti-monument. And that's how I see this work, that it's not glorifying the past, but it is also evoking non-heteronormative desires that are often cast as foreign and inauthentic. And I want my sculpture to challenge the viewer to imagine a different past, present, and future where tradition, culture, identity can be seen as impure, heterogeneous, and unstable, kind of always in process where taken for granted boundaries and art, historical, and national temporal boundaries can be disrupted.