Uprooted Order in Houston

A critical moment for Sikander came with her selection as a Core Fellow at the Glassell School of Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. During a period when few residencies provided artists the space and time to develop, Sikander was given two years (1995–97) to further explore the discoveries she had made at RISD. Houston, a region with its own cultural dynamics and history, stimulated Sikander’s creativity and dialogue with a broader spectrum of racial and diasporic communities.

In Texas, Sikander became more aware of racial complexities in the United States, including African American and civil rights histories and immigrant patterns and movements, all, she recalled, “magnifying my desire to understand the other in the shifting contentious multiplicity of the American sociocultural topography.” During this time, Sikander’s work increased in scale as she built wall-sized installations that combined her tracing-paper drawings. She also continued layering traditional painting with a growing personal vocabulary, producing work that quickly brought her to the fore of the American art world.

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

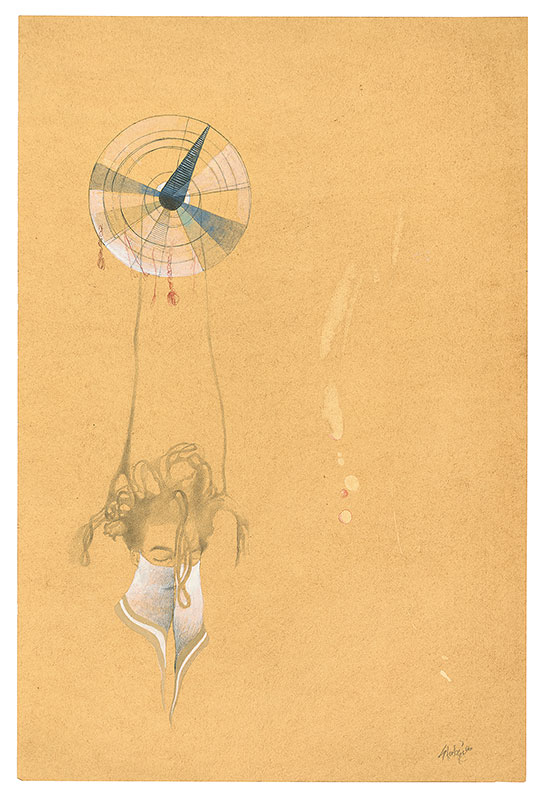

Pendulum

The pendulum was an apt symbol for Sikander, representing the nuanced spectrum of constantly shifting interpretations she encourages in her work. Some of the new vocabulary she developed in Houston revolved around signifiers of identity, especially hairstyle and clothing, as she questioned the stereotypes associated with them. Here, a self-portrait with an elaborate coiffure and a high collar masking her face functions as the pendulum’s weight. Sikander was exploring how outer appearances have historically been used to control and contain women.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Pendulum, 1996

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite, on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Mrs. Claire Ankenman

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Ready to Leave

Circles featured increasingly in Sikander’s lexicon in Houston, along with the griffin, an eagle-lion hybrid from Greek myth. “Under Alexander the Great, the Hellenic world extended to the Indian region of Punjab,” Sikander explains, “making the griffin a remnant from an earlier period of colonialization. I was connecting the griffin to the chalawa, a Punjabi term for a small farm animal that is now disappearing due to the region’s urbanization. The chalawa is a ghost. In my usage, it’s somebody who is so swift and transient, you can’t pin down who they are. I am identifying with the chalawa, resisting the routinely confronted categories: ‘Are you Muslim, Pakistani, artist, painter, Asian, Asian American, or what?’”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Ready to Leave, 1997

Watercolor, gouache, and ink, on tea-stained, marbled wasli paper

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from the Drawing Committee, 97.83.3

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: In the center of this painting, you see a female, but she's not showing her face. Alongside her is this hybrid Griffin, or what I call chalawa, a Punjabi term for a small, disappearing mythic farm animal. But here it functions as the poltergeist or the ghost, or even cultural amnesia. So in this painting, the visible yet obscured female and ghost are both symbolic of swift, transient, uncapturable characters. So this is my way of resisting some of these categories that I was confronting in the late '90s, things like, "Are you a practicing Muslim? Are you Pakistani, Asian, Asian-American, or what?" So this sort of questioning from all the multiple hyphenated states, whether Pakistani-American, Asian-American, Muslim-American, I kind of started to equate that porosity of categories to the breaching of national boundaries. And this work reflects that back and forth of being both invisible and hyper visible in the US by illuminating the very mercurial nature of identity because it's always only partially in our control. The rest comes from other people's perception of us.

Who’s Veiled Anyway?

Sikander explains this painting’s layered commentary on gender and religion: “The notion of the veil, despite its cliché, persists in defining the Muslim female in the West. This protagonist appears to be a veiled female, yet on close inspection one can see that the stock character is a male polo player common to South and Central Asian manuscript illustrations. Painting over the male figure with chalky white lines was my way to make androgyny the subject. One could read it as a comment on patriarchal, colonial, and imperial histories. It was also a means of tracing my own relationship with the largely male-dominated lineage of manuscript painting.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Who’s Veiled Anyway?, 1997

Watercolor and gouache on tea-stained wasli paper

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from the Drawing Committee, 97.83.1

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: I am not a fan of the broad categories such as Islam and the West, especially in contrast to each other. They remain opaque and polarizing, leading to frustrating conversations, hijacking people's imagination. Cliches about Muslim women, especially the stereotype of the veil, persist in Western history, literature, media. In the 1990s, I'd often experience the probing notion myself, especially when I wore my Pakistani clothes like the shalwar kameez with the scarf, seemingly Muslim by association. I wanted to respond, to raise questions from a variety of histories and representations, through exploring the writings of Fatima Mernissi, Edward Said, Frantz Fanon. The paradox of the veil took on a very deeply poignant platform. In my work, the idea is not about the object, but about unraveling the anxiety that it may foster. You see this protagonist... It could be read as an androgynous form. What you see is not what you expected. There's a male under the white line. The white line itself is like an editing tool for me. But I was also playing with Hélène Cixous' idea of the écriture féminine, often called white ink. The usage of white was also referencing the foundational element of the gadrang, the opaque color technique in miniature painting. White is used as the body for all colors. Using white paint as an editing tool to write with, literally and conceptually was also a play in this work on redaction and who gets to define the other in the collective imaginary.

Uprooted Order, Series 3, No. 1

A lotus floats over the central figure in this composition and acknowledges the umbilical cord as the literal life force of the mother. This multilayered avatar gives form to the heterogeneity of South Asia, which includes Jain, Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic, Sikh, Zoroastrian, and Christian cultures. “The central character’s attempt to pin down with its one foot the ghostlike female suggests the paradox of rootedness,” Sikander explains. “In a place like Houston, with its multiple immigrant narratives and nationalisms, the Uprooted Order series addressed the fallacy of assimilation versus foreignness.”

A lotus floats over the central figure in this composition and acknowledges the umbilical cord as the literal life force of the mother. This multilayered avatar gives form to the heterogeneity of South Asia, which includes Jain, Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic, Sikh, Zoroastrian, and Christian cultures. “The central character’s attempt to pin down with its one foot the ghostlike female suggests the paradox of rootedness,” Sikander explains. “In a place like Houston, with its multiple immigrant narratives and nationalisms, the Uprooted Order series addressed the fallacy of assimilation versus foreignness.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Uprooted Order, Series 3, No. 1, 1997

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Joseph Havel and Lisa Ludwig, 2003.728

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: What is being uprooted in this painting? This painting alludes broadly to the genre of Radha and Krishna, historical Indian paintings, except that there is no male in my work. I have removed the male deity, Krishna, to focus on the feminine and its empowering and hypnotic singular potential. The uprooted order transforms into the apparatus of power. So to begin, let me just share that while I was perusing Morgan's collections, I also came across a painting, which is on view in the vitrine outside the gallery. It's a work from 1825 called Krishna and Radha Beneath a Flowering Tree. There is some visual link between my work and the one from Morgan. In both the works, the female is balancing onto a blossomed branch. In this painting, while she is balancing, she's also pinning down with her foot a shadowy form in white, with looping feet and sort of wings. There are other iterations of this ghostlike creature at the top and left of the painting as if they are peeking into the painting itself, half inside, half outside. I was playing with paradoxes and exploring conflicting ideas to create tension and multivalence in my work. So there's sort of a dance happening between the idea of rootedness and being afloat, perhaps by choice.

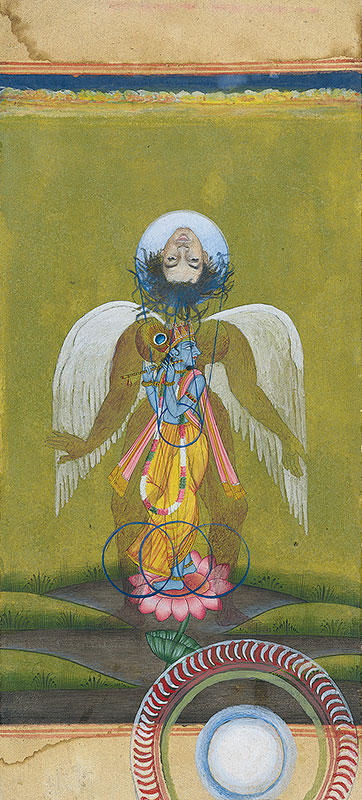

Uprooted Order I

Sikander’s ghostly figure merges in this work with Radha, a Hindu goddess and a gopi (consort of the god Krishna). Radha is often depicted in Hindu iconography as the god’s preferred lover. Here, however, Sikander presents Radha as an independent and powerful deity in her own right, excluding Krishna from the picture. A nude figure crouches at Radha’s legs and she holds to her chest a chalawa, a creature that typically cannot be confined.

By placing Radha on a lotus—a pedestal for many male deities in religions across Asia—Sikander shifts power to the female in all her multiplicity. The hand gesture illustrated at top is the yoni mudra, used to summon the energy of creation.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Uprooted Order I, 1997

Watercolor and gold paint on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of A. G. Rosen

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

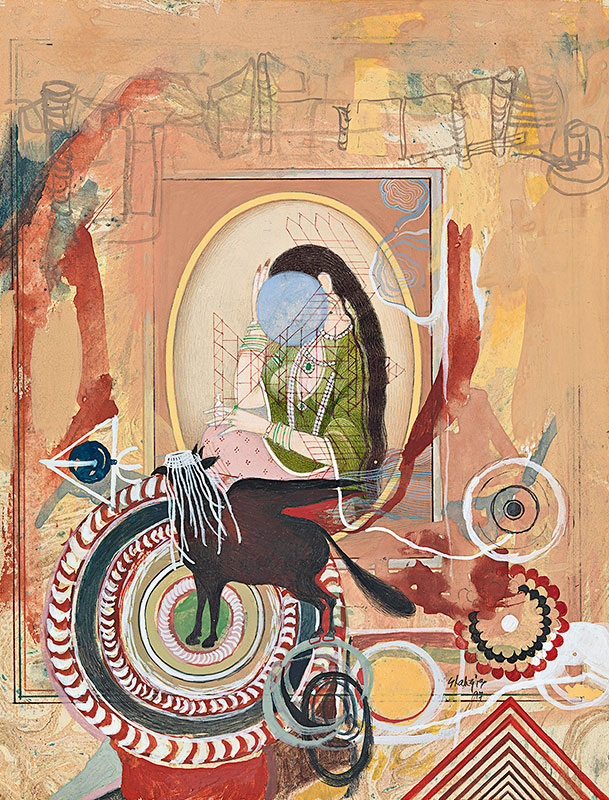

Uprooted Order 2

Sikander’s work often reimagines familiar figures to locate new interpretations and tell richer stories. She explains that this image could represent “the transmutation of the Hindu gods Krishna and Vishnu, an inversion of the Greek snake-haired Medusa, or the Greek hero Heracles with Krishna (being linked to the mythologies of the serpent monsters Hydra and Kaliya).” As in many of the works in her Uprooted Order series, Sikander presents tradition not as a static notion, but as “alive—a space of unexpected juxtapositions.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Uprooted Order 2, 1997

Watercolor and gold paint on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of A. G. Rosen

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Extraordinary Realities IV

Enthroned and dressed in red, Sikander floats in a bubble above a painting she found in a market in Houston’s Little India neighborhood. Perhaps in a nod to her new Texas home, she seems to lasso some unseen desire lying outside her sphere.

This work is one from a series of six collages, each using as its base a traditional manuscript painting made for tourists. Sikander overlaid the paintings with photographs taken in an installation she had mounted at Project Row Houses, a community revitalization project and art space. The series was part of her continued experiment in disrupting traditional narratives.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Extraordinary Realities IV, 1996

Photo collage and watercolor on found tourist painting, mounted to tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Lois Plehn, New York

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Bearings IV

Sikander acknowledges that she is driven by “an urgent reexamining of colonial and imperial stories of race and representation.” The many heads and circles in this work suggest the many lenses through which the artist or the viewer (who is the I eyeing in her title?) could, as Sikander says, “question the neat and tidy classification systems that control and maintain social structures.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Bearings IV, 1994–97

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of James Casebere

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Bearings

In Houston, Sikander was deeply involved in Project Row Houses, a housing and arts organization in the Third Ward, a predominantly African American neighborhood. This painting celebrates the organization with an upside-down portrait of its cofounder, the artist Rick Lowe, surrounded by various recontextualized images and icons. Sikander explains, “I wanted to counter derogatory representations of blackness in the medieval West—as seen in the silhouetted figures above the shields—through my construction of the armorial seal with the row houses. I also wanted to address politicized contemporary representations of the veil, and to reclaim positive representation for both. I am reimagining these entrenched and contested historical symbols by bringing them into conversation with overlapping diasporas.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Bearings, 1989–97

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Carol and Arthur Goldberg

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: Critical thinking, creativity, collaboration are three tenets on which I've built my entire understanding of being an artist. How culture, society, and economy intersect and how communities coalesce plays a role in how art functions in overlapping spaces. I moved to Houston in 1995 and my sense of community was being determined through my expanding experience of different cultures, different histories. And Houston had a small South Asian population also, so I made a lot of efforts to engage with the local Indians and Pakistanis, some students, some aspiring writers, but also started to bring them into the Third Ward of the African-American neighborhood where I was involved with the Project Row Houses. And I was aware of my role as a bridge between communities of color that would not otherwise interact. So this work is really about that time, about that moment. For me, engaging with artists and projects at the Third Ward was really instrumental in my understanding of the broader grasp of intersections of community and art. Project Row Houses, which is featured in both these works, was a shining example of the local community and collectives operating outside of the traditional spaces of power and narrative, where the local and everyday function at sites of transformation, where women, students, Third Ward residents, artists of color, thinkers, poets, musicians, social activists, everybody would come about and engage. This painting for me is really that reflection, a reflection upon race, gender, class, different languages as a means of contact, where I was actively seeking overlapping diasporas in the American landscape of racial differences.

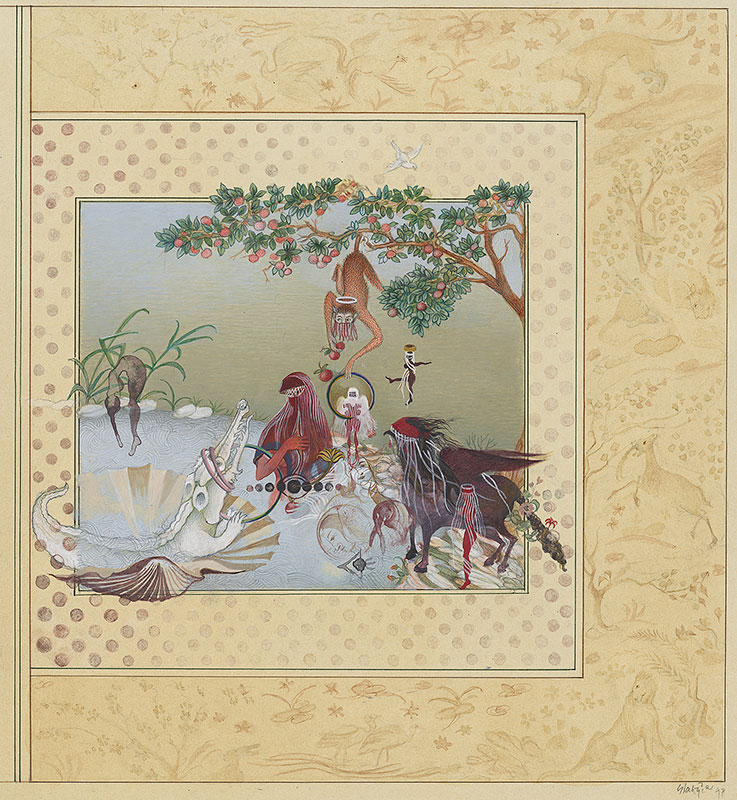

Venus's Wonderland

Barely contained within the decorative border of this painting is a fanciful cast of characters brought together from several different narratives. The biblical story of the serpent is reimagined here as a monkey tempting Eve to take a bite of the forbidden fruit. Eve is posed as Venus in Botticelli’s iconic painting The Birth of Venus, with the crocodile lying in her shell. Sikander’s use of animals to convey human traits is grounded in a collection of fables in the Persian illustrated manuscript tradition, Kalila wa-Dimna—itself a translation of the Panchatantra, an Indian fable collection written around the third century. Its story of the relationship between a crocodile and a monkey who lives in an apple tree is also referenced here.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Venus’s Wonderland, 1995–97

Watercolor and traces of graphite on tea-stained wasli paper

Rachel and Jean-Pierre Lehmann Collection

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Hood’s Red Rider No. 2

Cinderella’s prince holds her slipper at center while a powerful veiled heroine takes control above as a reimagined Red Riding Hood. Sikander explains, “European fairy tales, which carry deeply entrenched gender bias, were part of my childhood storybooks in Pakistan. When I started examining manuscript painting as a young adult, the passive depictions of women often perturbed me. I wanted to make female protagonists who were proactive, playful, confident, intelligent, and connected to the past in imaginative ways”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Hood’s Red Rider No. 2, 1997

Watercolor and gold paint on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Susan and Lew Manilow

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Cholee Kay Peechay Kiya? Chunree Kay Neechay Kiya?(What Is under the Blouse? What Is under the Dress?)

This work’s title is drawn from a song in the popular 1993 Bollywood film Khalnayak (The villain). In the scene in which the song plays, two women sensuously dance together while a man observes them. In Sikander’s response to the scene, the male figure has been left out.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Cholee Kay Peechay Kiya? Chunree Kay Neechay Kiya? (What Is under the Blouse? What Is under the Dress?), 1997

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Marieluise Hessel Collection, Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale- on-Hudson, New York

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: The title of this work references a song from a very famous Bollywood film. This was such a staple song in the 1990s. It was a mega hit song and also being performed at the parties and drag performances in queer spaces. So I didn't really start by creating an illustration of that song. It's just that the parallels started to emerge later. And when I was in conversation with the gender and sexuality scholar Gayatri Gopinath, who has written a essay in the book related to this exhibition, we started talking about how a queer optic can be used as a lens on reading so much of my work. And this reading that she brings to the work is really interesting to me as well, where she sees this gender and sexuality outside a conventional visual logic of secrecy and disclosure, invisibility and visibility. There is the body. The female body in this painting seems to exist in excess of gender itself. It sprouts limbs, lotuses, it endlessly repeats, doubles, multiplies, and then circles back on itself.

In Your Head and Not on My Feet

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

In Your Head and Not on My Feet, 1997

Graphite on paper

Collection of Susan and Lew Manilow

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Where Lies the Perfect Fit

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Where Lies the Perfect Fit, 1997

Graphite on paper

Collection of Susan and Lew Manilow

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.