A Pleasing Dislocation in Providence

Sikander’s extraordinary achievements in Pakistan were largely unknown in the United States—including to the faculty and students at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)—when she arrived to pursue an MFA in 1993. In Providence, as Sikander grappled with assumptions about her identity as a Pakistani woman, she applied the sensitivity to materials learned in Lahore as she experimented with new media and techniques with swiftness and abandon. Using different pressures and a large brush, she painted abstractly with ink, gouache, and later, watercolor. Gestural marks began to suggest recognizable, often figurative, shapes.

This new type of work allowed ideas to percolate and spill out without judgment or overthinking. “Some of the images,” Sikander stated at the time, “came out of recent acquaintances and memories of traditions, cultures, and experiences, combined with syncretic sculpture; South and Central Asian schools of painting (such as Pahari, Safavid, and Mughal); Celtic art; and Kufic calligraphy. The knitting together of these references and mythologies, as well as more private inner encounters, dreams, and fantasies, gave birth to my explorations of feminine power.”

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation

This unfinished panel was part of a fiftyfoot mural Sikander was commissioned to make for a New York law firm. The image’s powerful iconography suggests female resilience and potency. According to Sikander, “the referents are manifold: the Jewish Shekhina, or Saqueena in Quranic parlance—the feminine complement to the masculine divine—and the chthonic mother goddesses of the Indus Valley.” The hovering female avatar holds implements of both defense (weapons) and justice (a scale). After 9/11, the figure was misunderstood as referring to violence rather than inner strength. When asked to change it, Sikander instead withdrew from the commission.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation, 2001

Acrylic on board

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Pleasing Dislocation

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Pleasing Dislocation, 1995

Ink on tracing paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Intersectional Forms, Homage to Friendship

Sikander enjoys collaborating with like-minded artists. In this early example, the pastel monotype ground and central figure are the work of Donnamaria Bruton, a RISD professor who was Sikander’s close friend. As painters and women of color, they shared concerns about the white art world and patriarchal societies. This monstrous family-like grouping may reflect the malicious societal attitudes toward accomplished, ambitious women.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Donnamaria Bruton, American, 1954–2012 Intersectional Forms, Homage to Friendship, ca. 1994

Gouache over pastel monotype on gray paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Housed

The movement of Sikander’s brush, fully loaded with white gouache, is palpable in this depiction, yet the figural or architectural form itself remains ambiguous. The top portion, a face covering for a shuttlecock burka, is most clearly articulated. The haunted image responds to the Orientalist obsession with the veil in the Western imagination: Is it perforated armor, a shelter, a mask, or a shell? According to Sikander, “Housed is about the constraints of escaping an imprisoning representation. The cage-like form has a door, and a pink heart lurks inside. This painting tapped into my anxiety of being boxed into a stereotype on behalf of a culture or a religion.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Housed, 1995 Gouache and charcoal on clay-coated paperboard

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

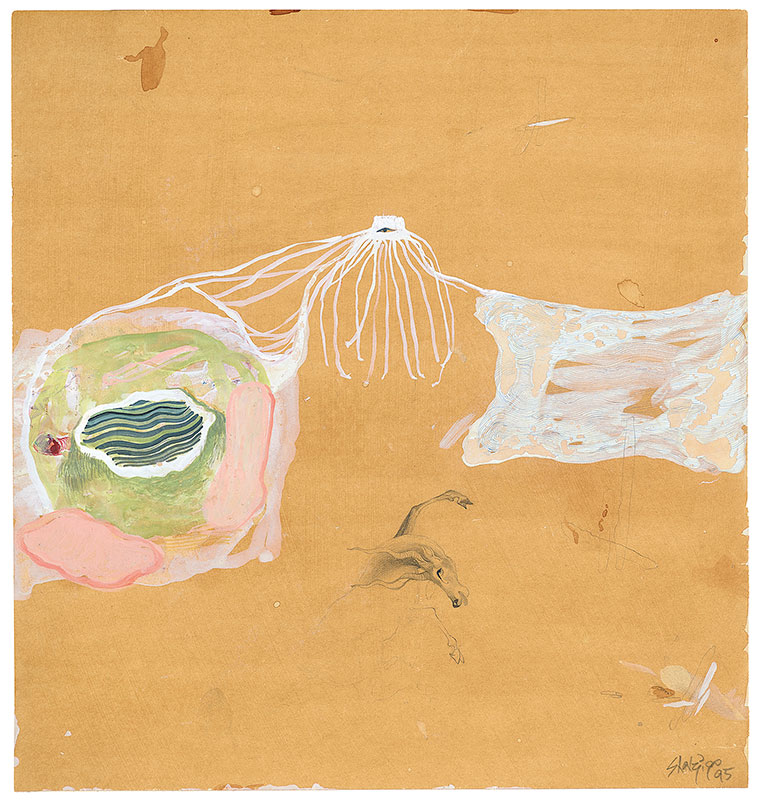

Spaces in Between

This is one of the earliest works that combined Sikander’s new gestural vocabulary with the precision of traditional manuscript painting. She freely applied gouache to teastained wasli paper, joining abstract shapes with what could be seen as a multilimbed creature or a shredded veil with an embedded eye. The color white references the ground layer to which color pigments are added in manuscript painting. Below, the delicately rendered, spiral-horned antelope could have come out of a manuscript illustration. Both creatures emphasize the gaze. Sikander asks, “Where lies the power, in the eye of the beholder or in the art itself?”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Spaces in Between, 1995

Gouache and graphite on tea-stained wasli paper

Private collection, Göttingen, Germany

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Self-Rooted

This double female representation exemplifies Sikander’s use of redrawing, reorienting, embellishing, and recontextualizing to arrive at new interpretations. Rendered here as a deity and its avatar, both with looping, “self-nourishing roots,” this figure would become an iconic image in Sikander’s lexicon. The figures are presented in conversation with each other: one vertical, active, buoyant, and light; the other horizontal, passive, grounded, and dark. The liquidity of the ink on the slick paper created an unusual mottled pattern that resembles skin.

Self-Rooted is one of Sikander’s earliest works to employ layered tracing paper—note the vertical lines showing through from the sheet below. The strategy would soon be central to her practice.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Self-Rooted, 1994

Ink and gouache on layered tracing paper

RISD Museum: Paula and Leonard Granoff Fund and Walter H. Kimball Fund 2020.28

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Dislocation

Sikander has described the genesis of Dislocation at length: “Forms like these sprung forth from my resisting the racial straitjacketing I encountered in the 1990s in America. The assumptions that were projected on to me about who I was or what I represented felt not just unfair but alien. Becoming the other, the outsider, through the prevalent and polarizing dichotomies of East-West, Islamic-Western, Asian-White, oppressive-free, led to an outburst of iconography of fragmented and severed bodies, androgynous forms, armless and headless torsos, and self-rooted, floating half-human figures. They refused to belong, to be fixed, to be grounded, or to be stereotyped.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Dislocation, ca. 1995

Ink on layered tracing paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Cycles and Transitions

In this work begun in Providence and reworked in Houston, Sikander used thin washes over areas of figuration to conflate bodies with the landscape. Female forms, in guises from comical to dark, resist categorization. “I was responding to my inability to locate Brown South-Asian representation in the feminist space in 1990s art-history books,” the artist recalled. “The monolithic category ‘third-world feminism’ felt offensive and limiting while it also pointed out white feminism’s blind spots and exclusions.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Cycles and Transitions, 1995–96

Watercolor and gouache on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Alton and Emily Steiner

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Let It Ride

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Let It Ride, 1995–96

Watercolor and gouache on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Alton and Emily Steiner

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Separate Working Things I

This work records the first time Sikander boldly painted over one of her meticulously crafted traditional compositions. Sunlike red flames extend to the sheet’s edges, creating a new image that feels both celebratory and destructive, drawing attention to and obliterating the central couple. The gesture, according to Sikander, “shatters the trope of ‘ideal love’ from within the Indian painting vernacular. The stock characters of the Lovers on Horseback (here from the celebrated story of Baz Bahadur and Rupmati) become the site for rupture, a destabilizing of the motif of heterosexual love itself.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Separate Working Things I, 1993–95

Watercolor and gold paint on tea-stained wasli paper

Private collection

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

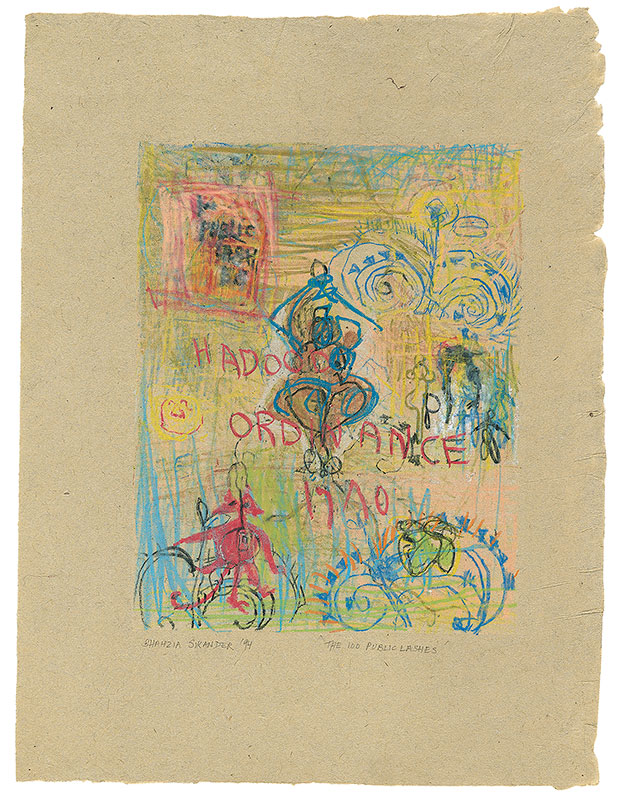

The 100 Public Lashes

In this work, a vigorously marked pastel monotype by Donnamaria Bruton serves as the base for Sikander’s own graffiti-like, emotional response to one of Pakistan’s Hudood Ordinances, introduced when she was ten. Unmarried women victimized by rape or accused of adultery were threatened with public lashings, as intimated at the center of this image. Deformed bodies and coiled designs resembling ovaries or watchful eyes surround the spectacle.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

The 100 Public Lashes, 1994

Pastel monotype and pastel on tan paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.