Studying in Lahore

In 1987, Sikander enrolled at Lahore’s National College of Arts (NCA) and began her study of manuscript painting—or miniature painting, as the discipline is referred to there. It was an unexpected choice for a major. Western models of art instruction prevailed at the NCA, and although the miniature had long been taught, a major had only been established in 1982, by Professor Bashir Ahmad; it was not considered a path for an ambitious artist. “I chose the medium,” Sikander explains, “when it was widely considered craft, with no room allowed for creative expression, because I perceived a frontier.”

Sikander was the first student at the NCA to develop an intense mentorship with Ahmad, delving deeply into the discipline’s history, techniques, and styles. Ahmad supported Sikander’s deviation from the thesis requirements to create one monumental work, The Scroll (1989–90), which received significant attention and acclaim. Sikander’s success led to increased enrollment in the NCA program, her appointment as a lecturer in miniature painting at the school, and the start of a so-called neominiature movement.

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

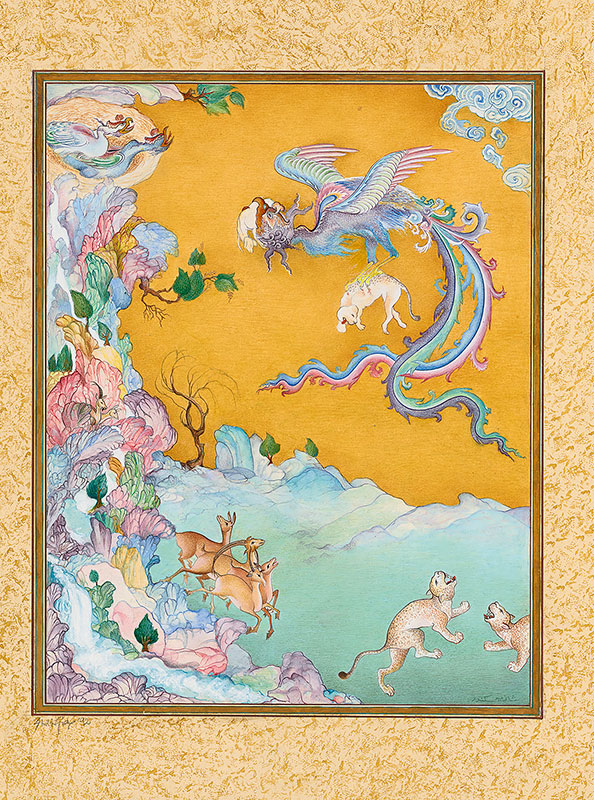

Simurgh Study after "Zal Is Sighted by a Caravan," Attributed to Abdul Aziz

This scene—an example of Sikander’s early interest in fantastic creatures—refers to the extraordinary sixteenth-century manuscript known as the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp, now disassembled. Based on a leaf at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Sikander’s version focuses on the simurgh, a magical bird from Persian mythology. The simurgh symbolizes divinity in the twelfth-century Sufi allegorical tale The Conference of the Birds. In Islamic belief, birds in flight are associated with the ascension of the soul to a higher realm. Birds are rich in personal meaning for Sikander, who frequently equates them with imagination.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Simurgh Study after “Zal Is Sighted by a Caravan,” Attributed to Abdul Aziz, 1988

Watercolor on wasli paper

Collection of William Drew and Ruth Davis

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: This work is very important for me for several reasons. It references a page from the acclaimed illustrated 16th-century manuscript Shah Tahmasp Shahnama, which later was called the Houghton Shahnama, after the collector, Arthur Houghton, who in 1960s started to disassemble the manuscript into separate folios, many of which are now housed at Met. It's a very fascinating story of provenance. It is important in my practice to follow the provenance of objects, to understand the history of much of Islamic art in how it came to be in Western museum's collections. So the Shahnama is over 50,000 rhyming couplets. It was authored by the 10th century Persian poet Firdausi. The poem narrates the history of the ancient kings of Iran and is both mythical and historical. There is in there the allegorical tale of the simurgh, who also appears in another Persian poet's work, Farid-al-Din-Attar, who wrote the epic poem Conference of the Birds, which is a Sufi or mystical work where a flock of birds journey in pursuit of the mythical simurgh, a metaphor for the search of truth and enlightenment. So in many cases, simurgh is a female. It is always sort of hovering in the space between earth and sky. It's often seen simultaneously, near and far; visible, invisible; colorless or full of colors. And that's exactly the topic that I wanted to explore as a young artist.

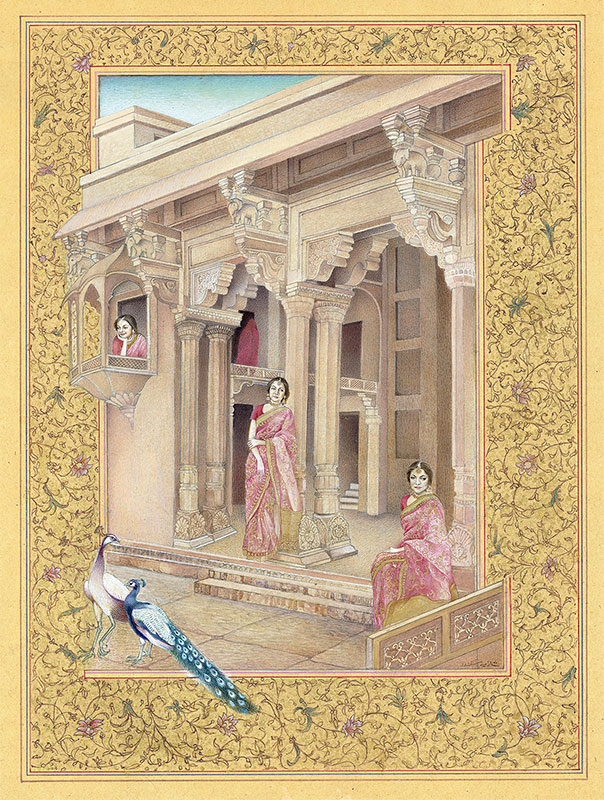

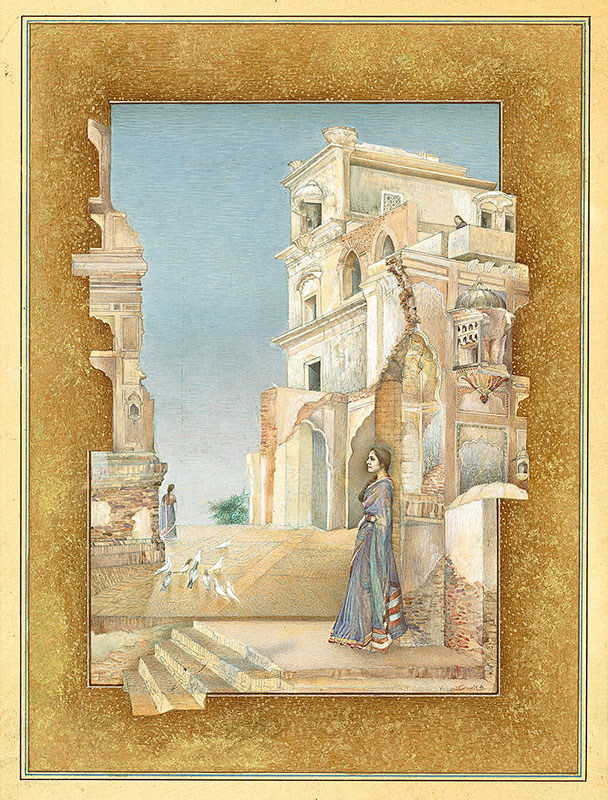

Mirrat I and Mirrat II

In these two compositions that preserve the format of manuscript illustrations and its decorative framing, Sikander portrays her friend Mirrat. In Mirrat I, she appears at Lahore Fort, a citadel in the capital city. Mirrat II shows her in an empty Sikh haveli, a historical home abandoned after the partition of India and Pakistan. The repetition of the figure suggests the passage of time—a traditional device in Mughal paintings. Sikander adapted the manuscript trope of the waiting woman by depicting Mirrat with a range of nuanced, contemplative expressions.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Mirrat I and Mirrat II, 1989–90

Watercolor and gold leaf on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

The Scroll

In this composition, her NCA thesis, Sikander depicted herself within a house inspired by her teenage home and rendered in a style that references Safavid painting traditions. “I am a floating ghostlike presence in every chapter or segment,” she said, “privy to the unfolding narrative while functioning as a channel through which an observer can access and navigate the painting. My diaphanous moving and morphing form is rendered in white gouache, and one can never see my face. I was making a statement on the restlessness of youth and the quest for identity. The claiming of the freedom for the female body in the domestic setting.” Although the portrayal is informed by a range of traditions, everything about The Scroll—its subject, format, setting, and details—was newly imagined. Painted over a year and a half, this was a breakthrough work not just for Sikander but also for the viability of manuscript painting traditions for contemporary practice.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

The Scroll, 1989–90

Watercolor and gouache on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: This painting was a turning point in Pakistan, launching contemporary miniature and laying to rest the national debate about miniature tradition's inability to engage the youth. I was only 19 when I started this work, and the research is done in that era, in the '80s when there's the Afghan-Pak, US-Soviet War unfolding in the region. It's marked by a diminishing women's rights. I was inspired by women all around me, Pakistani women activists, artists, poets, all my female friends. So in this piece, you see this young woman stepping over a threshold symbolized as a frame. You see her taking herself and others along into a new territory, a new beginning. The painting reads left to right. At the end, you see the girl in white painting a self-portrait. It's sort of a triangular relationship with herself. Whose portrait is she looking at? Throughout the work, there's a lot of detail and the space expands and contracts. I'm looking at Chinese scroll paintings, the Safavid School. I'm looking at David Hockney, K.G Subramanyan, Satyajit Ray's use of narrative in his films. I was also looking at many Mughal sites in Pakistan, a lot of the actual architecture. So this painting takes all these references and asserts itself in the form of a epic poem. That's how I see it. And there's a playfulness in choosing the format of a scroll also, because it naturally lends itself to depicting a narrative about time or an unfolding of an event, a story, a day, or a lifetime.

The Scroll II

In this more abstract version of The Scroll, Sikander refers to the tradition of the Gandharan Buddhist birch-bark scrolls. She incorporates bark into the painting, inscribing its materiality with light and form to extract a psychological dimension from the space. The activity in this series of vignettes is visually linked yet mysterious. Seen through windows and mirrors, the figures depicted feel hidden. At the center of the composition a woman lies on the ground, seemingly shattered by the bark and the house itself.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

The Scroll II, 1991 Watercolor on bark and tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Munazzah and Tariq Malik

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Miniature in Mughal Style: Imaginary Man

Sikander made this drawing as an exercise in traditional manuscript painting, employing the practice passed on to her by Bashir Ahmad, her professor at the NCA. The method starts with preparing the paper. Dampened cotton-fiber sheets are layered together with wheat-starch paste and a preservative. After the paper is pressed and dried, both sides are burnished with a sea shell, creating a smooth, luminous surface. For this work, the paper was also stained with several applications of tea. Using a brush fitted with only a few hairs, Sikander carefully outlined the image. She then applied layers of transparent wash and gold leaf. Like several other works in the exhibition, this painting was completed over a number of years—typical of Sikander’s process then and now.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Miniature in Mughal Style: Imaginary Man, 1991–92

Ink and gold leaf on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Anu and Arjun Aggarwal

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Study of Figure

This full-color painting was likely completed while Sikander was teaching at the NCA, as an example to show students. Once the paper had been prepared and the design transferred to the sheet, watercolor was carefully added using a dry brush. In this technique, called pardakht, the painting’s color is built up through many layers of quick, short brushstrokes, adeptly and meditatively applied with a minimum of pigment to avoid disrupting the delicate surface. The richness and depth achieved by this method is noticeable throughout the sheet, even in the white cloth.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Study of Figure, 1992

Watercolor on wasli paper

Collection of Elaine and Barry Fain

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Study of "The Lovers" by Riza-yi ‘Abbasi

This painting is based on a Safavid work— dated to seventeenth-century Iran—in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which Sikander copied from a reproduction. Although copying historical examples was part of the training at the NCA, students had little access to original works: due to the legacy of colonialism, most South and Central Asian manuscript illustrations now reside in Western museums. “My first visual encounter with miniature painting was with its facsimile,” Sikander recalled. “But even in printed reproductions, the inherent eroticism and beauty of the works captivated my imagination and challenged my assumptions.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Study of “The Lovers” by Riza-yi ‘Abbasi, 1991

Watercolor on wasli paper

Collection of Roger and Gayle Mandle

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Riding the Written

Sikander’s appreciation of language is expressed in her work through the wit of titles and her incorporation of script. In this example, the calligraphy of horses in motion was inspired by her childhood experience of reciting and memorizing the Quran in Arabic before understanding it in Urdu or English. “The ritual was to first get acquainted with the aural and visual before the meaning. It resulted in this amazing visual memory where the beauty of the Arabic script superseded everything else.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Riding the Written, 1992

Screen print over handmade marbled paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.