Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities

Born and raised in Pakistan, Shahzia Sikander (b. 1969) gained international recognition in the 1990s for her pioneering role in bringing painting traditions from South and Central Asia into dialogue with contemporary practices. Her work interrogates cultural identity, racial narratives, colonial and postcolonial histories, and issues of gender and sexuality. Through multivalent narratives layered across time, geography, and tradition, she shatters established hierarchies, norms, and stereotypes, using her imagination and playfulness to conjure extraordinary realities.

This exhibition explores the first fifteen years of Sikander’s career, from her formal training in manuscript painting as a student at the National College of Arts in Lahore, Pakistan, where she enrolled in 1987, to her early years in the United States. Sikander moved to Providence in 1993 to study at the Rhode Island School of Design. She then lived in Houston for two years before settling in New York in 1997. Her work during this period reflects a new openness in the United States toward artists working outside of commonly accepted models as well as a dramatic shift in the perception of Muslims following the events of 9/11. The potent vocabulary of Sikander’s early work continues to permeate her oeuvre today, and the subjects she confronted then have only become more relevant to contemporary discourse.

Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities is organized by the RISD Museum and presented in collaboration with the Morgan Library & Museum.

This exhibition is made possible at the Morgan Library & Museum by lead corporate support from Morgan Stanley.

![]()

Additional support is provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art; Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon Polsky; Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin M. Rosen; and Sean and Mary Kelly and Sean Kelly Gallery.

This exhibition originated at the RISD Museum with grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Scintilla Foundation, and the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc. Additional publication support from the Vikram and Geetanjali Kirloskar Visiting Scholar in Painting Endowed Fund at the Rhode Island School of Design and Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund.

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

Colin B Bailey: Hello, I'm Colin B. Bailey, director of the Morgan Library Museum, and I'm delighted to welcome you to Shazia Sikandar: Extraordinary Realities. Born in Pakistan, Sikandar gained international recognition in the 1990s for her refined and exquisite paintings in which she subverted the tradition of Indo-Persian manuscript illumination. The exhibition follows her during the first 15 years of her career, from her rigorous training in Lahore, Pakistan, to her move to Providence, Rhode Island, and eventually to New York, where the events of 9/11 had a profound influence on her work. In images of great subtlety and power, Sikandar's art investigates burning contemporary issues related to feminism, migrations, colonialism, and cultural boundaries. As you move through the gallery, look for the audio symbols to discover commentary from the artist herself who will share with you the circumstances in which she made the drawings, what her sources of inspiration were and how she developed her imagery. Thank you for joining us at the Morgan. We hope you enjoy your visit.

Overview

Gallery Images

Virtual Tour

Studying in Lahore

In 1987, Sikander enrolled at Lahore’s National College of Arts (NCA) and began her study of manuscript painting—or miniature painting, as the discipline is referred to there. It was an unexpected choice for a major. Western models of art instruction prevailed at the NCA, and although the miniature had long been taught, a major had only been established in 1982, by Professor Bashir Ahmad; it was not considered a path for an ambitious artist. “I chose the medium,” Sikander explains, “when it was widely considered craft, with no room allowed for creative expression, because I perceived a frontier.”

Sikander was the first student at the NCA to develop an intense mentorship with Ahmad, delving deeply into the discipline’s history, techniques, and styles. Ahmad supported Sikander’s deviation from the thesis requirements to create one monumental work, The Scroll (1989–90), which received significant attention and acclaim. Sikander’s success led to increased enrollment in the NCA program, her appointment as a lecturer in miniature painting at the school, and the start of a so-called neominiature movement.

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

Simurgh Study after "Zal Is Sighted by a Caravan," Attributed to Abdul Aziz

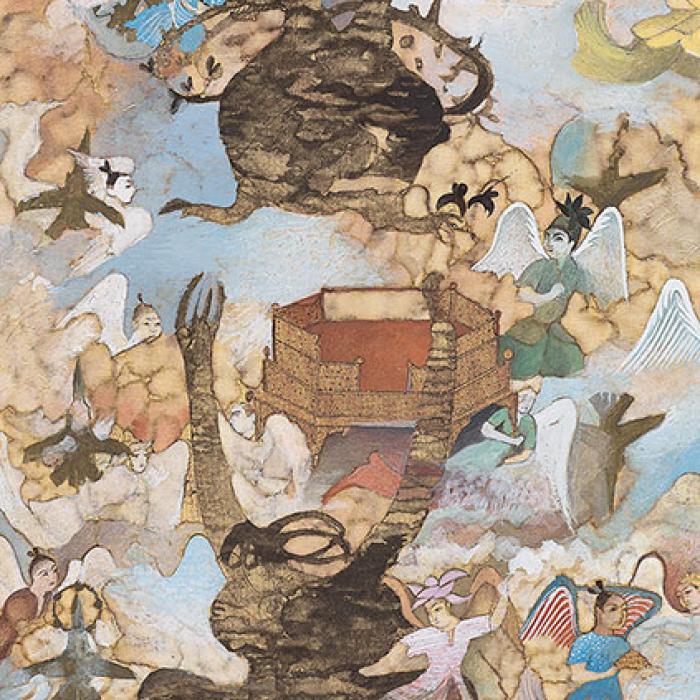

This scene—an example of Sikander’s early interest in fantastic creatures—refers to the extraordinary sixteenth-century manuscript known as the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp, now disassembled. Based on a leaf at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Sikander’s version focuses on the simurgh, a magical bird from Persian mythology. The simurgh symbolizes divinity in the twelfth-century Sufi allegorical tale The Conference of the Birds. In Islamic belief, birds in flight are associated with the ascension of the soul to a higher realm. Birds are rich in personal meaning for Sikander, who frequently equates them with imagination.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Simurgh Study after “Zal Is Sighted by a Caravan,” Attributed to Abdul Aziz, 1988

Watercolor on wasli paper

Collection of William Drew and Ruth Davis

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: This work is very important for me for several reasons. It references a page from the acclaimed illustrated 16th-century manuscript Shah Tahmasp Shahnama, which later was called the Houghton Shahnama, after the collector, Arthur Houghton, who in 1960s started to disassemble the manuscript into separate folios, many of which are now housed at Met. It's a very fascinating story of provenance. It is important in my practice to follow the provenance of objects, to understand the history of much of Islamic art in how it came to be in Western museum's collections. So the Shahnama is over 50,000 rhyming couplets. It was authored by the 10th century Persian poet Firdausi. The poem narrates the history of the ancient kings of Iran and is both mythical and historical. There is in there the allegorical tale of the simurgh, who also appears in another Persian poet's work, Farid-al-Din-Attar, who wrote the epic poem Conference of the Birds, which is a Sufi or mystical work where a flock of birds journey in pursuit of the mythical simurgh, a metaphor for the search of truth and enlightenment. So in many cases, simurgh is a female. It is always sort of hovering in the space between earth and sky. It's often seen simultaneously, near and far; visible, invisible; colorless or full of colors. And that's exactly the topic that I wanted to explore as a young artist.

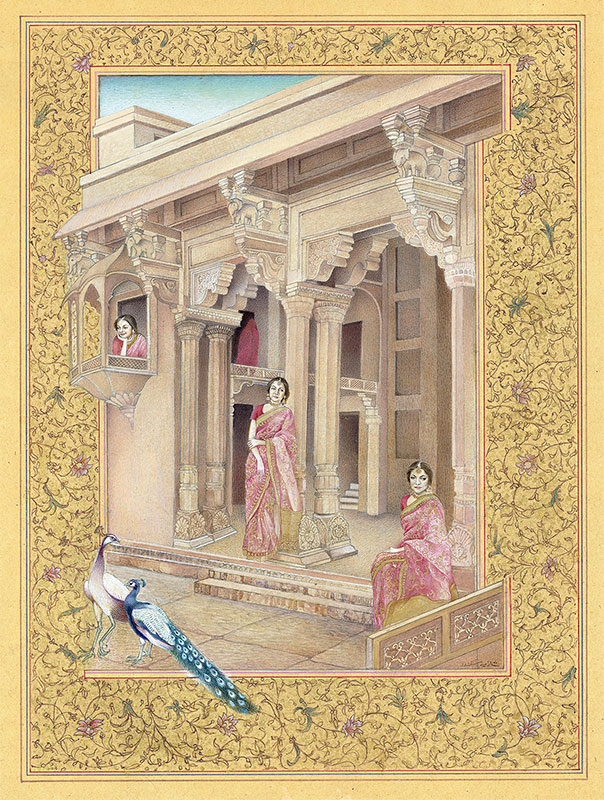

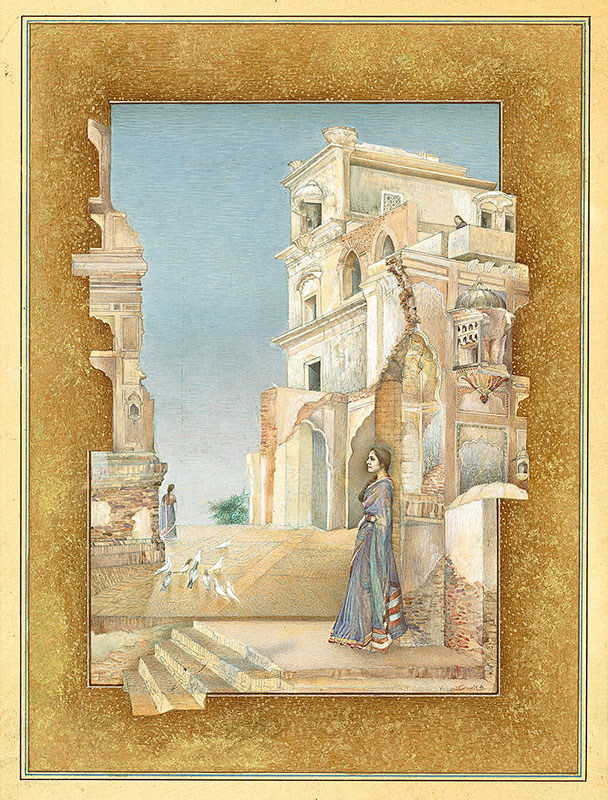

Mirrat I and Mirrat II

In these two compositions that preserve the format of manuscript illustrations and its decorative framing, Sikander portrays her friend Mirrat. In Mirrat I, she appears at Lahore Fort, a citadel in the capital city. Mirrat II shows her in an empty Sikh haveli, a historical home abandoned after the partition of India and Pakistan. The repetition of the figure suggests the passage of time—a traditional device in Mughal paintings. Sikander adapted the manuscript trope of the waiting woman by depicting Mirrat with a range of nuanced, contemplative expressions.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Mirrat I and Mirrat II, 1989–90

Watercolor and gold leaf on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

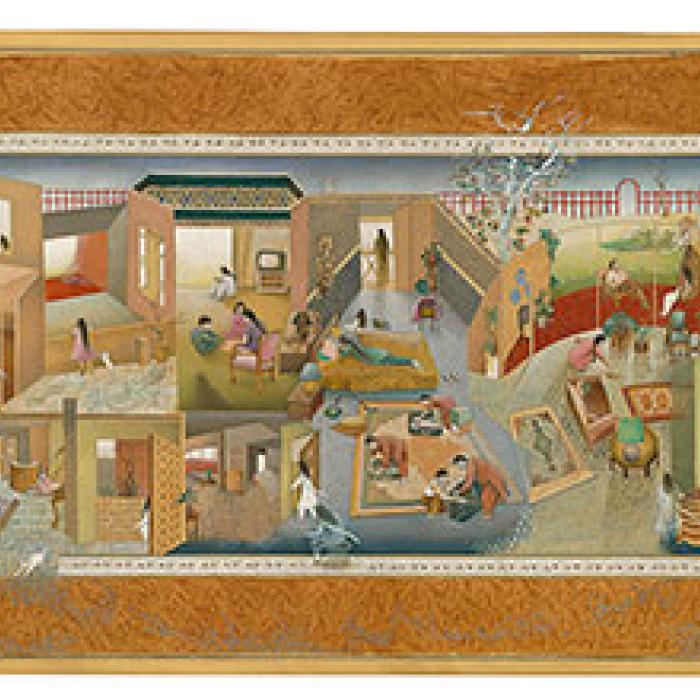

The Scroll

In this composition, her NCA thesis, Sikander depicted herself within a house inspired by her teenage home and rendered in a style that references Safavid painting traditions. “I am a floating ghostlike presence in every chapter or segment,” she said, “privy to the unfolding narrative while functioning as a channel through which an observer can access and navigate the painting. My diaphanous moving and morphing form is rendered in white gouache, and one can never see my face. I was making a statement on the restlessness of youth and the quest for identity. The claiming of the freedom for the female body in the domestic setting.” Although the portrayal is informed by a range of traditions, everything about The Scroll—its subject, format, setting, and details—was newly imagined. Painted over a year and a half, this was a breakthrough work not just for Sikander but also for the viability of manuscript painting traditions for contemporary practice.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

The Scroll, 1989–90

Watercolor and gouache on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: This painting was a turning point in Pakistan, launching contemporary miniature and laying to rest the national debate about miniature tradition's inability to engage the youth. I was only 19 when I started this work, and the research is done in that era, in the '80s when there's the Afghan-Pak, US-Soviet War unfolding in the region. It's marked by a diminishing women's rights. I was inspired by women all around me, Pakistani women activists, artists, poets, all my female friends. So in this piece, you see this young woman stepping over a threshold symbolized as a frame. You see her taking herself and others along into a new territory, a new beginning. The painting reads left to right. At the end, you see the girl in white painting a self-portrait. It's sort of a triangular relationship with herself. Whose portrait is she looking at? Throughout the work, there's a lot of detail and the space expands and contracts. I'm looking at Chinese scroll paintings, the Safavid School. I'm looking at David Hockney, K.G Subramanyan, Satyajit Ray's use of narrative in his films. I was also looking at many Mughal sites in Pakistan, a lot of the actual architecture. So this painting takes all these references and asserts itself in the form of a epic poem. That's how I see it. And there's a playfulness in choosing the format of a scroll also, because it naturally lends itself to depicting a narrative about time or an unfolding of an event, a story, a day, or a lifetime.

The Scroll II

In this more abstract version of The Scroll, Sikander refers to the tradition of the Gandharan Buddhist birch-bark scrolls. She incorporates bark into the painting, inscribing its materiality with light and form to extract a psychological dimension from the space. The activity in this series of vignettes is visually linked yet mysterious. Seen through windows and mirrors, the figures depicted feel hidden. At the center of the composition a woman lies on the ground, seemingly shattered by the bark and the house itself.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

The Scroll II, 1991 Watercolor on bark and tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Munazzah and Tariq Malik

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Miniature in Mughal Style: Imaginary Man

Sikander made this drawing as an exercise in traditional manuscript painting, employing the practice passed on to her by Bashir Ahmad, her professor at the NCA. The method starts with preparing the paper. Dampened cotton-fiber sheets are layered together with wheat-starch paste and a preservative. After the paper is pressed and dried, both sides are burnished with a sea shell, creating a smooth, luminous surface. For this work, the paper was also stained with several applications of tea. Using a brush fitted with only a few hairs, Sikander carefully outlined the image. She then applied layers of transparent wash and gold leaf. Like several other works in the exhibition, this painting was completed over a number of years—typical of Sikander’s process then and now.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Miniature in Mughal Style: Imaginary Man, 1991–92

Ink and gold leaf on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Anu and Arjun Aggarwal

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

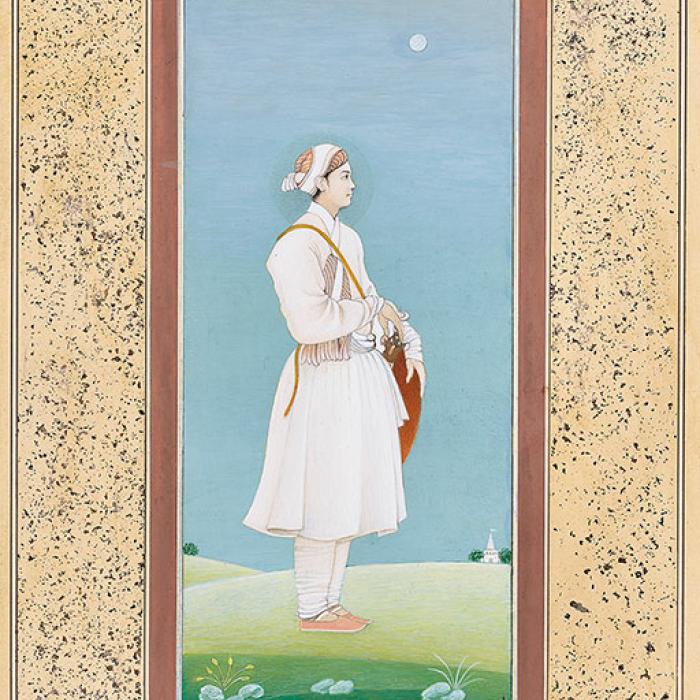

Study of Figure

This full-color painting was likely completed while Sikander was teaching at the NCA, as an example to show students. Once the paper had been prepared and the design transferred to the sheet, watercolor was carefully added using a dry brush. In this technique, called pardakht, the painting’s color is built up through many layers of quick, short brushstrokes, adeptly and meditatively applied with a minimum of pigment to avoid disrupting the delicate surface. The richness and depth achieved by this method is noticeable throughout the sheet, even in the white cloth.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Study of Figure, 1992

Watercolor on wasli paper

Collection of Elaine and Barry Fain

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

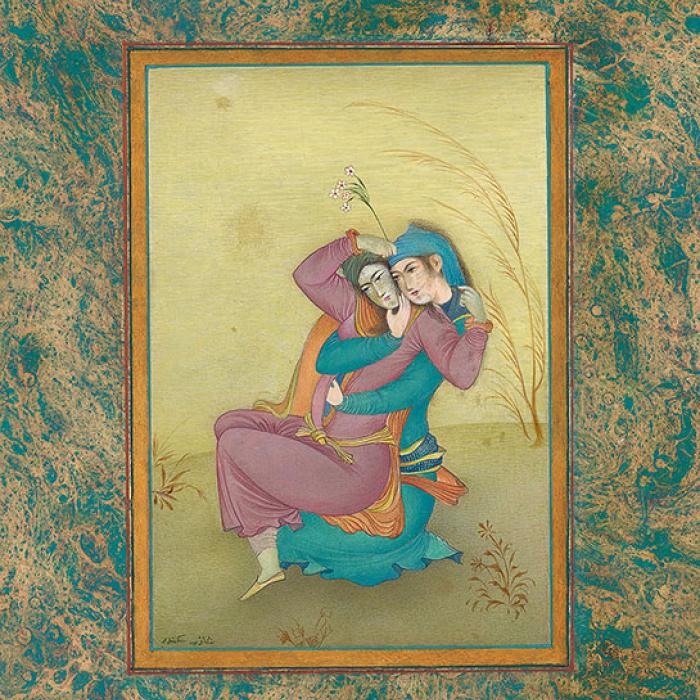

Study of "The Lovers" by Riza-yi ‘Abbasi

This painting is based on a Safavid work— dated to seventeenth-century Iran—in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which Sikander copied from a reproduction. Although copying historical examples was part of the training at the NCA, students had little access to original works: due to the legacy of colonialism, most South and Central Asian manuscript illustrations now reside in Western museums. “My first visual encounter with miniature painting was with its facsimile,” Sikander recalled. “But even in printed reproductions, the inherent eroticism and beauty of the works captivated my imagination and challenged my assumptions.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Study of “The Lovers” by Riza-yi ‘Abbasi, 1991

Watercolor on wasli paper

Collection of Roger and Gayle Mandle

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

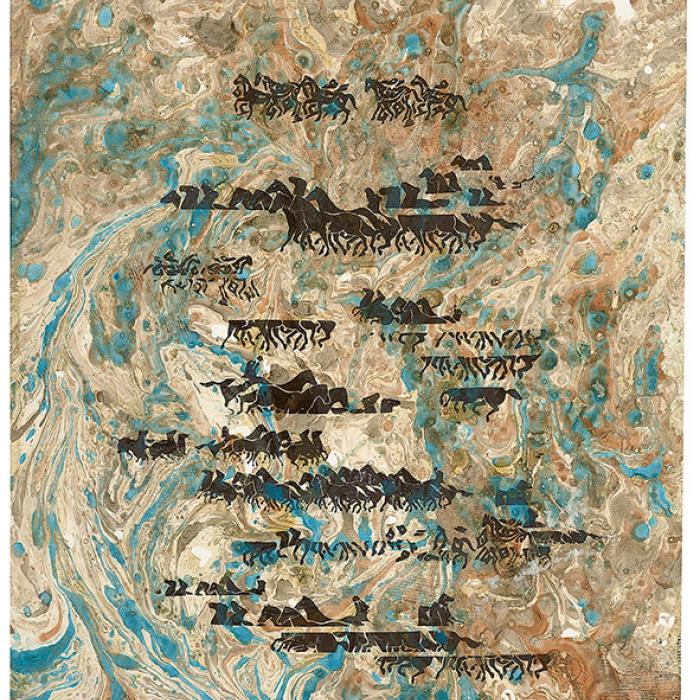

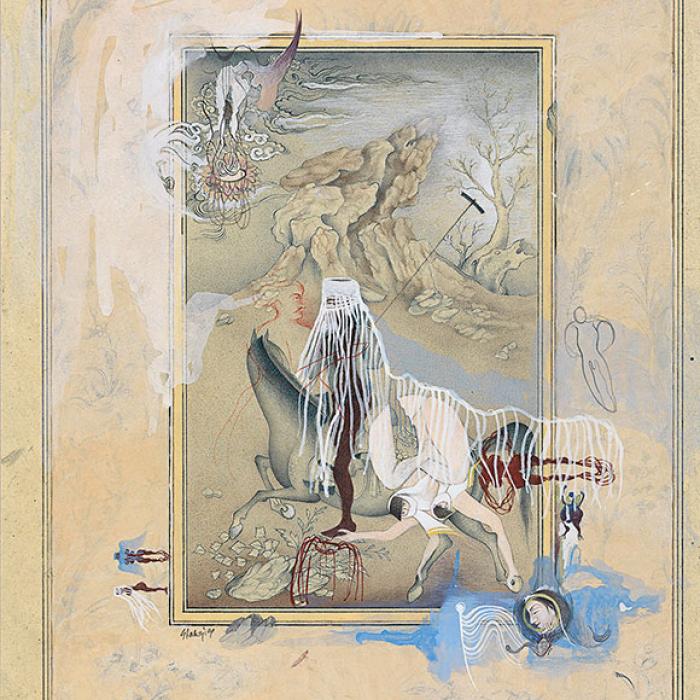

Riding the Written

Sikander’s appreciation of language is expressed in her work through the wit of titles and her incorporation of script. In this example, the calligraphy of horses in motion was inspired by her childhood experience of reciting and memorizing the Quran in Arabic before understanding it in Urdu or English. “The ritual was to first get acquainted with the aural and visual before the meaning. It resulted in this amazing visual memory where the beauty of the Arabic script superseded everything else.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Riding the Written, 1992

Screen print over handmade marbled paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

A Pleasing Dislocation in Providence

Sikander’s extraordinary achievements in Pakistan were largely unknown in the United States—including to the faculty and students at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)—when she arrived to pursue an MFA in 1993. In Providence, as Sikander grappled with assumptions about her identity as a Pakistani woman, she applied the sensitivity to materials learned in Lahore as she experimented with new media and techniques with swiftness and abandon. Using different pressures and a large brush, she painted abstractly with ink, gouache, and later, watercolor. Gestural marks began to suggest recognizable, often figurative, shapes.

This new type of work allowed ideas to percolate and spill out without judgment or overthinking. “Some of the images,” Sikander stated at the time, “came out of recent acquaintances and memories of traditions, cultures, and experiences, combined with syncretic sculpture; South and Central Asian schools of painting (such as Pahari, Safavid, and Mughal); Celtic art; and Kufic calligraphy. The knitting together of these references and mythologies, as well as more private inner encounters, dreams, and fantasies, gave birth to my explorations of feminine power.”

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation

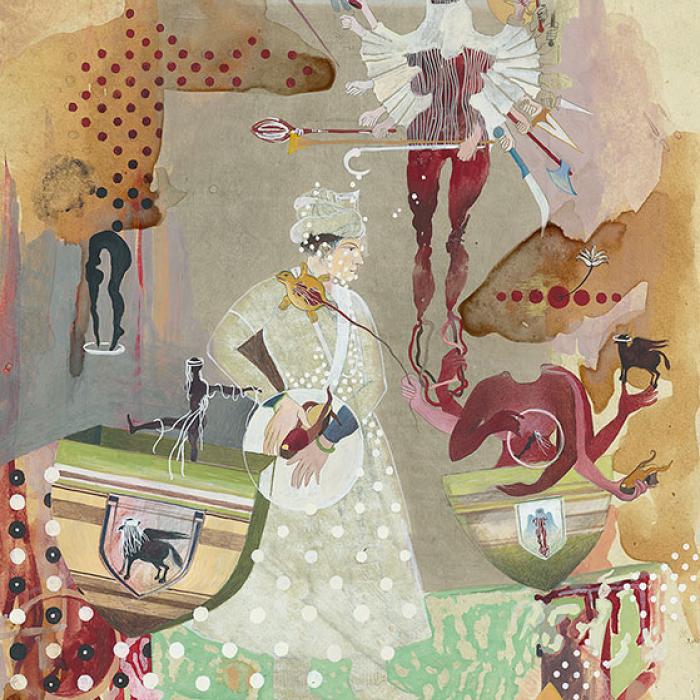

This unfinished panel was part of a fiftyfoot mural Sikander was commissioned to make for a New York law firm. The image’s powerful iconography suggests female resilience and potency. According to Sikander, “the referents are manifold: the Jewish Shekhina, or Saqueena in Quranic parlance—the feminine complement to the masculine divine—and the chthonic mother goddesses of the Indus Valley.” The hovering female avatar holds implements of both defense (weapons) and justice (a scale). After 9/11, the figure was misunderstood as referring to violence rather than inner strength. When asked to change it, Sikander instead withdrew from the commission.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation, 2001

Acrylic on board

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Pleasing Dislocation

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Pleasing Dislocation, 1995

Ink on tracing paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

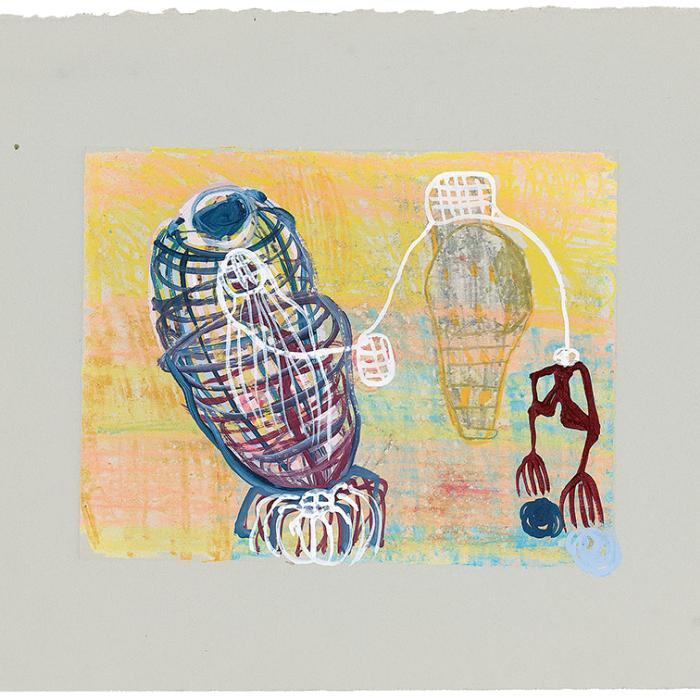

Intersectional Forms, Homage to Friendship

Sikander enjoys collaborating with like-minded artists. In this early example, the pastel monotype ground and central figure are the work of Donnamaria Bruton, a RISD professor who was Sikander’s close friend. As painters and women of color, they shared concerns about the white art world and patriarchal societies. This monstrous family-like grouping may reflect the malicious societal attitudes toward accomplished, ambitious women.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Donnamaria Bruton, American, 1954–2012 Intersectional Forms, Homage to Friendship, ca. 1994

Gouache over pastel monotype on gray paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Housed

The movement of Sikander’s brush, fully loaded with white gouache, is palpable in this depiction, yet the figural or architectural form itself remains ambiguous. The top portion, a face covering for a shuttlecock burka, is most clearly articulated. The haunted image responds to the Orientalist obsession with the veil in the Western imagination: Is it perforated armor, a shelter, a mask, or a shell? According to Sikander, “Housed is about the constraints of escaping an imprisoning representation. The cage-like form has a door, and a pink heart lurks inside. This painting tapped into my anxiety of being boxed into a stereotype on behalf of a culture or a religion.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Housed, 1995 Gouache and charcoal on clay-coated paperboard

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

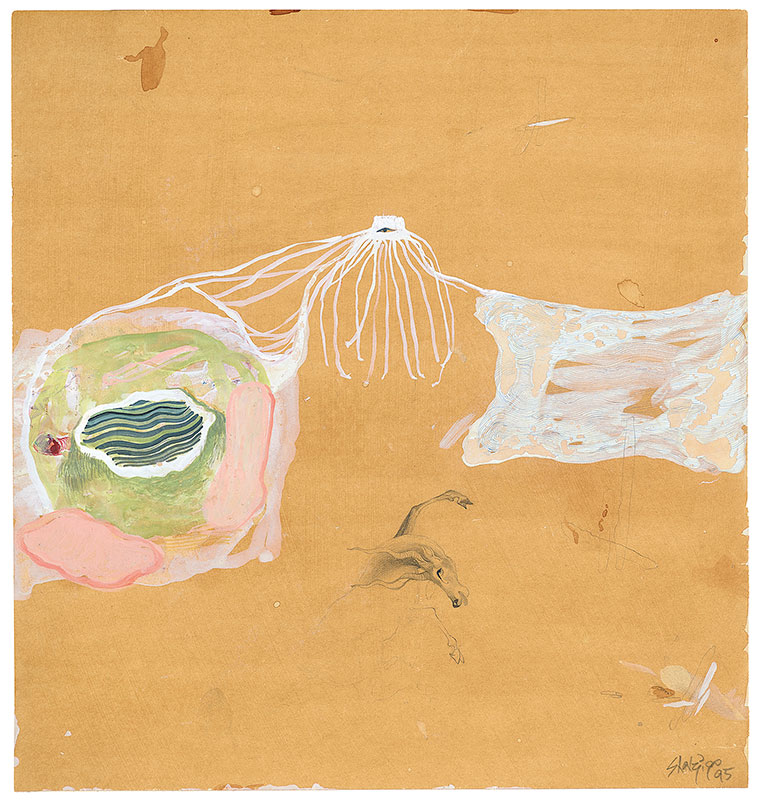

Spaces in Between

This is one of the earliest works that combined Sikander’s new gestural vocabulary with the precision of traditional manuscript painting. She freely applied gouache to teastained wasli paper, joining abstract shapes with what could be seen as a multilimbed creature or a shredded veil with an embedded eye. The color white references the ground layer to which color pigments are added in manuscript painting. Below, the delicately rendered, spiral-horned antelope could have come out of a manuscript illustration. Both creatures emphasize the gaze. Sikander asks, “Where lies the power, in the eye of the beholder or in the art itself?”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Spaces in Between, 1995

Gouache and graphite on tea-stained wasli paper

Private collection, Göttingen, Germany

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

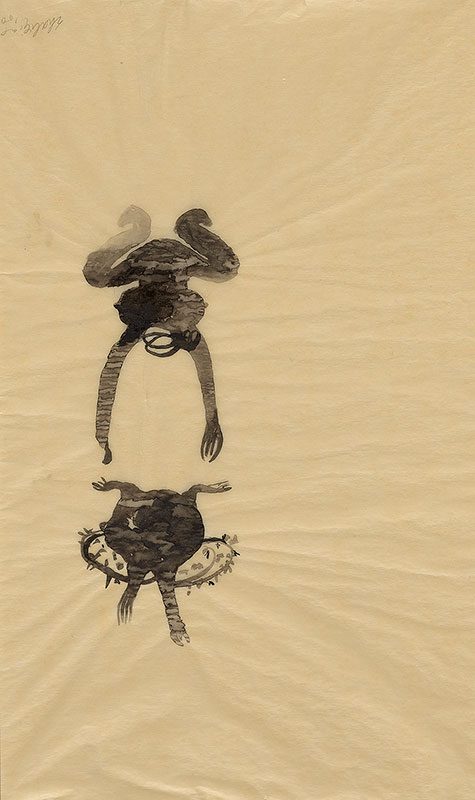

Self-Rooted

This double female representation exemplifies Sikander’s use of redrawing, reorienting, embellishing, and recontextualizing to arrive at new interpretations. Rendered here as a deity and its avatar, both with looping, “self-nourishing roots,” this figure would become an iconic image in Sikander’s lexicon. The figures are presented in conversation with each other: one vertical, active, buoyant, and light; the other horizontal, passive, grounded, and dark. The liquidity of the ink on the slick paper created an unusual mottled pattern that resembles skin.

Self-Rooted is one of Sikander’s earliest works to employ layered tracing paper—note the vertical lines showing through from the sheet below. The strategy would soon be central to her practice.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Self-Rooted, 1994

Ink and gouache on layered tracing paper

RISD Museum: Paula and Leonard Granoff Fund and Walter H. Kimball Fund 2020.28

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

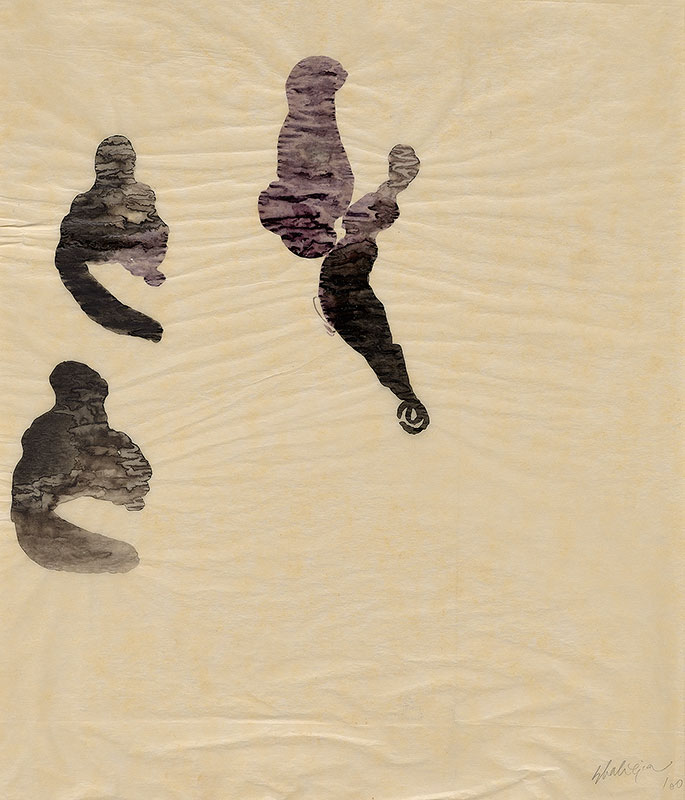

Dislocation

Sikander has described the genesis of Dislocation at length: “Forms like these sprung forth from my resisting the racial straitjacketing I encountered in the 1990s in America. The assumptions that were projected on to me about who I was or what I represented felt not just unfair but alien. Becoming the other, the outsider, through the prevalent and polarizing dichotomies of East-West, Islamic-Western, Asian-White, oppressive-free, led to an outburst of iconography of fragmented and severed bodies, androgynous forms, armless and headless torsos, and self-rooted, floating half-human figures. They refused to belong, to be fixed, to be grounded, or to be stereotyped.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Dislocation, ca. 1995

Ink on layered tracing paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Cycles and Transitions

In this work begun in Providence and reworked in Houston, Sikander used thin washes over areas of figuration to conflate bodies with the landscape. Female forms, in guises from comical to dark, resist categorization. “I was responding to my inability to locate Brown South-Asian representation in the feminist space in 1990s art-history books,” the artist recalled. “The monolithic category ‘third-world feminism’ felt offensive and limiting while it also pointed out white feminism’s blind spots and exclusions.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Cycles and Transitions, 1995–96

Watercolor and gouache on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Alton and Emily Steiner

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: My journey as a visual artist, to explore the personal as political, had already started in Pakistan. And now when I was in the US in the early 90s, this distancing from home started the process of self-actualization. I was holding onto my link with manuscript painting. I wanted to continue exploring it to see how it could yield new narratives and languages. And at the same time, many people were not familiar with the history of manuscript painting. So there was a little bit of this burden that I carried in the MFA program because my work was engaging with traditions that did not necessarily sit at the center of Western art history. So often, the work would be glossed over and interpreted very narrowly in terms of my biography. So this painting is more of a gesture of questioning and resisting the straightjacketing that often artists of color encounter. Who I was, what I represented became limiting constructs. So I was not making autobiographical works, but I wanted to talk about broader issues, about the complicated history of colonial legacies, orientalist constructs, lack of South Asian feminist representations, especially in the 1990s art history books. So when you see these forms, some are held in silos and some are bleeding through the gesture of ink, there's a lot of mixing and merging happening, a form of dislocation that starts to occur in this work.

Let It Ride

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Let It Ride, 1995–96

Watercolor and gouache on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Alton and Emily Steiner

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

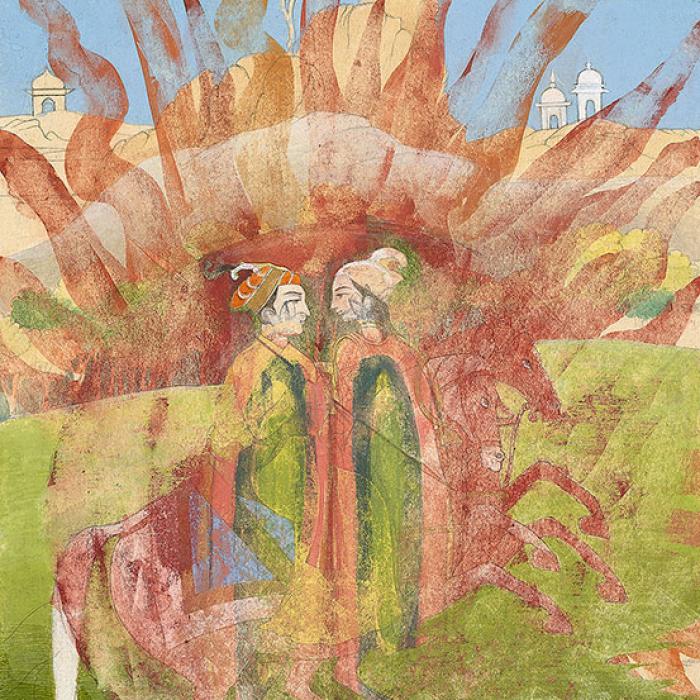

Separate Working Things I

This work records the first time Sikander boldly painted over one of her meticulously crafted traditional compositions. Sunlike red flames extend to the sheet’s edges, creating a new image that feels both celebratory and destructive, drawing attention to and obliterating the central couple. The gesture, according to Sikander, “shatters the trope of ‘ideal love’ from within the Indian painting vernacular. The stock characters of the Lovers on Horseback (here from the celebrated story of Baz Bahadur and Rupmati) become the site for rupture, a destabilizing of the motif of heterosexual love itself.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Separate Working Things I, 1993–95

Watercolor and gold paint on tea-stained wasli paper

Private collection

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

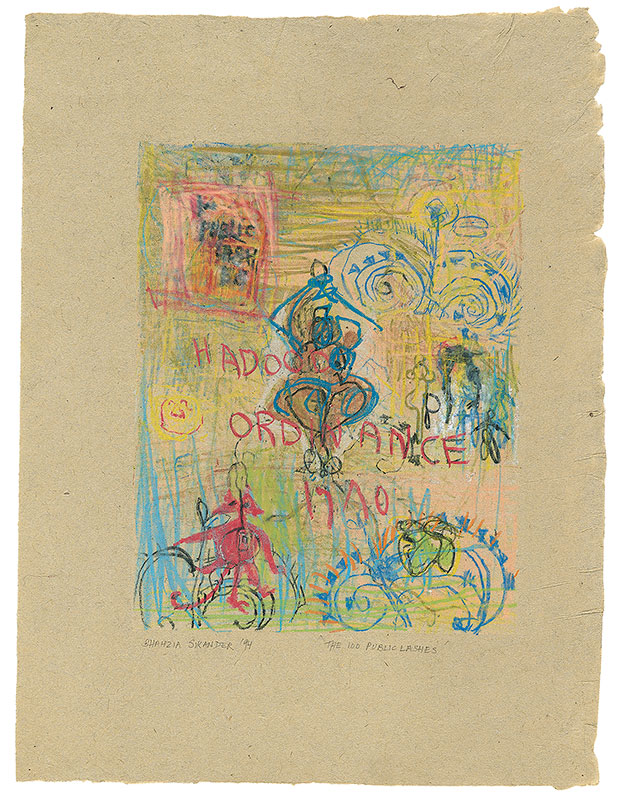

The 100 Public Lashes

In this work, a vigorously marked pastel monotype by Donnamaria Bruton serves as the base for Sikander’s own graffiti-like, emotional response to one of Pakistan’s Hudood Ordinances, introduced when she was ten. Unmarried women victimized by rape or accused of adultery were threatened with public lashings, as intimated at the center of this image. Deformed bodies and coiled designs resembling ovaries or watchful eyes surround the spectacle.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

The 100 Public Lashes, 1994

Pastel monotype and pastel on tan paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Uprooted Order in Houston

A critical moment for Sikander came with her selection as a Core Fellow at the Glassell School of Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. During a period when few residencies provided artists the space and time to develop, Sikander was given two years (1995–97) to further explore the discoveries she had made at RISD. Houston, a region with its own cultural dynamics and history, stimulated Sikander’s creativity and dialogue with a broader spectrum of racial and diasporic communities.

In Texas, Sikander became more aware of racial complexities in the United States, including African American and civil rights histories and immigrant patterns and movements, all, she recalled, “magnifying my desire to understand the other in the shifting contentious multiplicity of the American sociocultural topography.” During this time, Sikander’s work increased in scale as she built wall-sized installations that combined her tracing-paper drawings. She also continued layering traditional painting with a growing personal vocabulary, producing work that quickly brought her to the fore of the American art world.

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

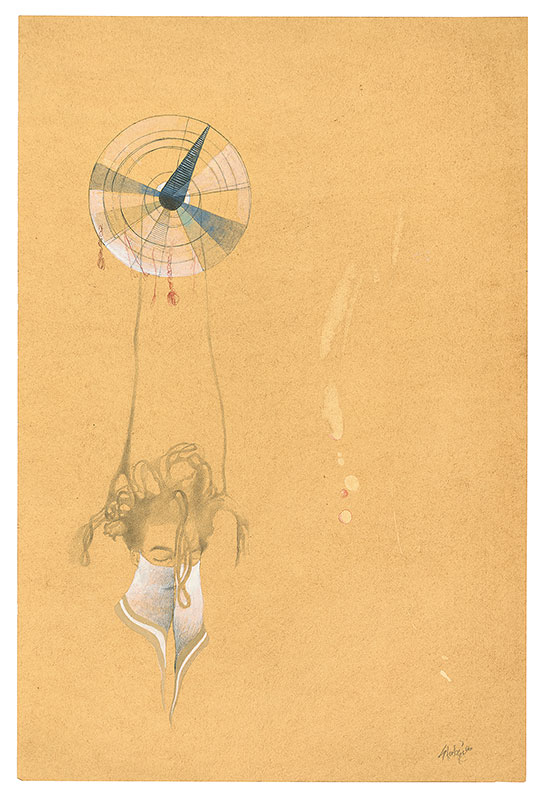

Pendulum

The pendulum was an apt symbol for Sikander, representing the nuanced spectrum of constantly shifting interpretations she encourages in her work. Some of the new vocabulary she developed in Houston revolved around signifiers of identity, especially hairstyle and clothing, as she questioned the stereotypes associated with them. Here, a self-portrait with an elaborate coiffure and a high collar masking her face functions as the pendulum’s weight. Sikander was exploring how outer appearances have historically been used to control and contain women.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Pendulum, 1996

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite, on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Mrs. Claire Ankenman

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Ready to Leave

Circles featured increasingly in Sikander’s lexicon in Houston, along with the griffin, an eagle-lion hybrid from Greek myth. “Under Alexander the Great, the Hellenic world extended to the Indian region of Punjab,” Sikander explains, “making the griffin a remnant from an earlier period of colonialization. I was connecting the griffin to the chalawa, a Punjabi term for a small farm animal that is now disappearing due to the region’s urbanization. The chalawa is a ghost. In my usage, it’s somebody who is so swift and transient, you can’t pin down who they are. I am identifying with the chalawa, resisting the routinely confronted categories: ‘Are you Muslim, Pakistani, artist, painter, Asian, Asian American, or what?’”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Ready to Leave, 1997

Watercolor, gouache, and ink, on tea-stained, marbled wasli paper

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from the Drawing Committee, 97.83.3

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: In the center of this painting, you see a female, but she's not showing her face. Alongside her is this hybrid Griffin, or what I call chalawa, a Punjabi term for a small, disappearing mythic farm animal. But here it functions as the poltergeist or the ghost, or even cultural amnesia. So in this painting, the visible yet obscured female and ghost are both symbolic of swift, transient, uncapturable characters. So this is my way of resisting some of these categories that I was confronting in the late '90s, things like, "Are you a practicing Muslim? Are you Pakistani, Asian, Asian-American, or what?" So this sort of questioning from all the multiple hyphenated states, whether Pakistani-American, Asian-American, Muslim-American, I kind of started to equate that porosity of categories to the breaching of national boundaries. And this work reflects that back and forth of being both invisible and hyper visible in the US by illuminating the very mercurial nature of identity because it's always only partially in our control. The rest comes from other people's perception of us.

Who’s Veiled Anyway?

Sikander explains this painting’s layered commentary on gender and religion: “The notion of the veil, despite its cliché, persists in defining the Muslim female in the West. This protagonist appears to be a veiled female, yet on close inspection one can see that the stock character is a male polo player common to South and Central Asian manuscript illustrations. Painting over the male figure with chalky white lines was my way to make androgyny the subject. One could read it as a comment on patriarchal, colonial, and imperial histories. It was also a means of tracing my own relationship with the largely male-dominated lineage of manuscript painting.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Who’s Veiled Anyway?, 1997

Watercolor and gouache on tea-stained wasli paper

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from the Drawing Committee, 97.83.1

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: I am not a fan of the broad categories such as Islam and the West, especially in contrast to each other. They remain opaque and polarizing, leading to frustrating conversations, hijacking people's imagination. Cliches about Muslim women, especially the stereotype of the veil, persist in Western history, literature, media. In the 1990s, I'd often experience the probing notion myself, especially when I wore my Pakistani clothes like the shalwar kameez with the scarf, seemingly Muslim by association. I wanted to respond, to raise questions from a variety of histories and representations, through exploring the writings of Fatima Mernissi, Edward Said, Frantz Fanon. The paradox of the veil took on a very deeply poignant platform. In my work, the idea is not about the object, but about unraveling the anxiety that it may foster. You see this protagonist... It could be read as an androgynous form. What you see is not what you expected. There's a male under the white line. The white line itself is like an editing tool for me. But I was also playing with Hélène Cixous' idea of the écriture féminine, often called white ink. The usage of white was also referencing the foundational element of the gadrang, the opaque color technique in miniature painting. White is used as the body for all colors. Using white paint as an editing tool to write with, literally and conceptually was also a play in this work on redaction and who gets to define the other in the collective imaginary.

Uprooted Order, Series 3, No. 1

A lotus floats over the central figure in this composition and acknowledges the umbilical cord as the literal life force of the mother. This multilayered avatar gives form to the heterogeneity of South Asia, which includes Jain, Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic, Sikh, Zoroastrian, and Christian cultures. “The central character’s attempt to pin down with its one foot the ghostlike female suggests the paradox of rootedness,” Sikander explains. “In a place like Houston, with its multiple immigrant narratives and nationalisms, the Uprooted Order series addressed the fallacy of assimilation versus foreignness.”

A lotus floats over the central figure in this composition and acknowledges the umbilical cord as the literal life force of the mother. This multilayered avatar gives form to the heterogeneity of South Asia, which includes Jain, Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic, Sikh, Zoroastrian, and Christian cultures. “The central character’s attempt to pin down with its one foot the ghostlike female suggests the paradox of rootedness,” Sikander explains. “In a place like Houston, with its multiple immigrant narratives and nationalisms, the Uprooted Order series addressed the fallacy of assimilation versus foreignness.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Uprooted Order, Series 3, No. 1, 1997

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Joseph Havel and Lisa Ludwig, 2003.728

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

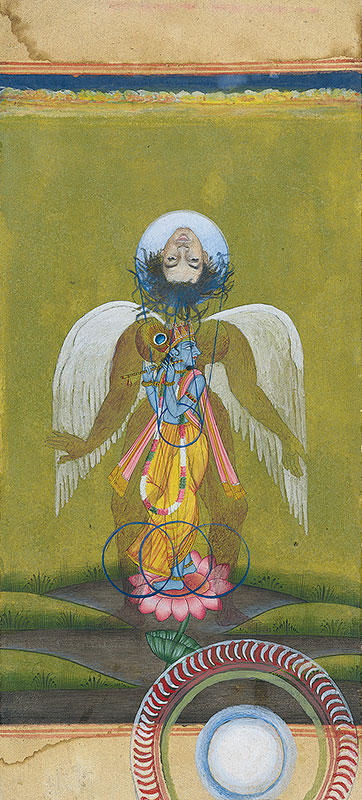

Shazia Sikandar: What is being uprooted in this painting? This painting alludes broadly to the genre of Radha and Krishna, historical Indian paintings, except that there is no male in my work. I have removed the male deity, Krishna, to focus on the feminine and its empowering and hypnotic singular potential. The uprooted order transforms into the apparatus of power. So to begin, let me just share that while I was perusing Morgan's collections, I also came across a painting, which is on view in the vitrine outside the gallery. It's a work from 1825 called Krishna and Radha Beneath a Flowering Tree. There is some visual link between my work and the one from Morgan. In both the works, the female is balancing onto a blossomed branch. In this painting, while she is balancing, she's also pinning down with her foot a shadowy form in white, with looping feet and sort of wings. There are other iterations of this ghostlike creature at the top and left of the painting as if they are peeking into the painting itself, half inside, half outside. I was playing with paradoxes and exploring conflicting ideas to create tension and multivalence in my work. So there's sort of a dance happening between the idea of rootedness and being afloat, perhaps by choice.

Uprooted Order I

Sikander’s ghostly figure merges in this work with Radha, a Hindu goddess and a gopi (consort of the god Krishna). Radha is often depicted in Hindu iconography as the god’s preferred lover. Here, however, Sikander presents Radha as an independent and powerful deity in her own right, excluding Krishna from the picture. A nude figure crouches at Radha’s legs and she holds to her chest a chalawa, a creature that typically cannot be confined.

By placing Radha on a lotus—a pedestal for many male deities in religions across Asia—Sikander shifts power to the female in all her multiplicity. The hand gesture illustrated at top is the yoni mudra, used to summon the energy of creation.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Uprooted Order I, 1997

Watercolor and gold paint on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of A. G. Rosen

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Uprooted Order 2

Sikander’s work often reimagines familiar figures to locate new interpretations and tell richer stories. She explains that this image could represent “the transmutation of the Hindu gods Krishna and Vishnu, an inversion of the Greek snake-haired Medusa, or the Greek hero Heracles with Krishna (being linked to the mythologies of the serpent monsters Hydra and Kaliya).” As in many of the works in her Uprooted Order series, Sikander presents tradition not as a static notion, but as “alive—a space of unexpected juxtapositions.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Uprooted Order 2, 1997

Watercolor and gold paint on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of A. G. Rosen

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

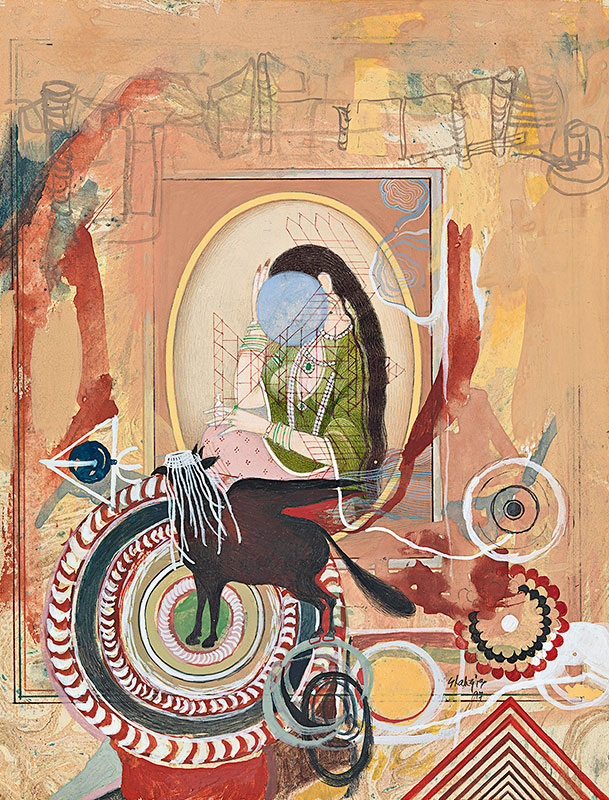

Extraordinary Realities IV

Enthroned and dressed in red, Sikander floats in a bubble above a painting she found in a market in Houston’s Little India neighborhood. Perhaps in a nod to her new Texas home, she seems to lasso some unseen desire lying outside her sphere.

This work is one from a series of six collages, each using as its base a traditional manuscript painting made for tourists. Sikander overlaid the paintings with photographs taken in an installation she had mounted at Project Row Houses, a community revitalization project and art space. The series was part of her continued experiment in disrupting traditional narratives.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Extraordinary Realities IV, 1996

Photo collage and watercolor on found tourist painting, mounted to tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Lois Plehn, New York

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Bearings IV

Sikander acknowledges that she is driven by “an urgent reexamining of colonial and imperial stories of race and representation.” The many heads and circles in this work suggest the many lenses through which the artist or the viewer (who is the I eyeing in her title?) could, as Sikander says, “question the neat and tidy classification systems that control and maintain social structures.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Bearings IV, 1994–97

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of James Casebere

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Bearings

In Houston, Sikander was deeply involved in Project Row Houses, a housing and arts organization in the Third Ward, a predominantly African American neighborhood. This painting celebrates the organization with an upside-down portrait of its cofounder, the artist Rick Lowe, surrounded by various recontextualized images and icons. Sikander explains, “I wanted to counter derogatory representations of blackness in the medieval West—as seen in the silhouetted figures above the shields—through my construction of the armorial seal with the row houses. I also wanted to address politicized contemporary representations of the veil, and to reclaim positive representation for both. I am reimagining these entrenched and contested historical symbols by bringing them into conversation with overlapping diasporas.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Bearings, 1989–97

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Carol and Arthur Goldberg

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: Critical thinking, creativity, collaboration are three tenets on which I've built my entire understanding of being an artist. How culture, society, and economy intersect and how communities coalesce plays a role in how art functions in overlapping spaces. I moved to Houston in 1995 and my sense of community was being determined through my expanding experience of different cultures, different histories. And Houston had a small South Asian population also, so I made a lot of efforts to engage with the local Indians and Pakistanis, some students, some aspiring writers, but also started to bring them into the Third Ward of the African-American neighborhood where I was involved with the Project Row Houses. And I was aware of my role as a bridge between communities of color that would not otherwise interact. So this work is really about that time, about that moment. For me, engaging with artists and projects at the Third Ward was really instrumental in my understanding of the broader grasp of intersections of community and art. Project Row Houses, which is featured in both these works, was a shining example of the local community and collectives operating outside of the traditional spaces of power and narrative, where the local and everyday function at sites of transformation, where women, students, Third Ward residents, artists of color, thinkers, poets, musicians, social activists, everybody would come about and engage. This painting for me is really that reflection, a reflection upon race, gender, class, different languages as a means of contact, where I was actively seeking overlapping diasporas in the American landscape of racial differences.

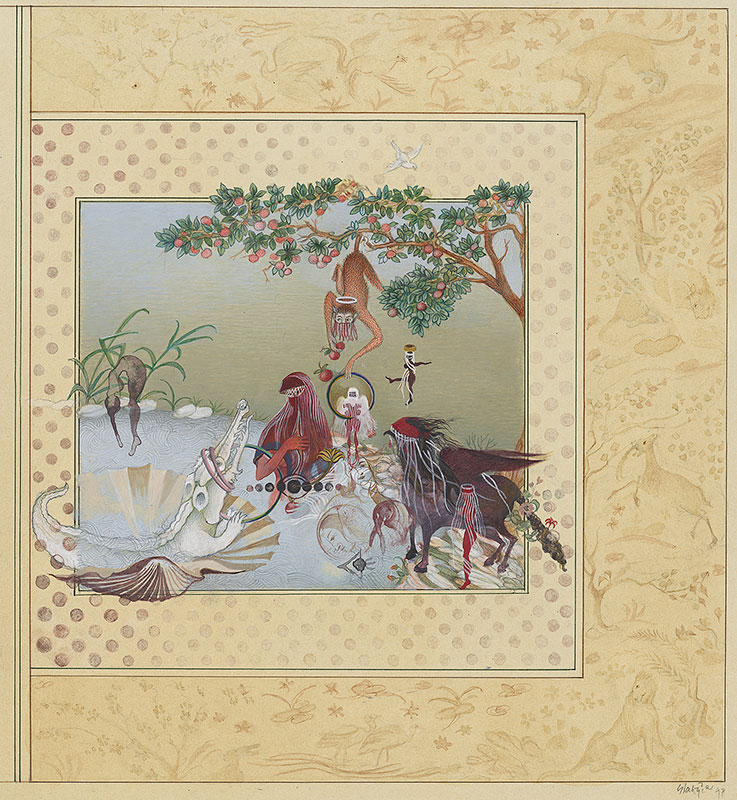

Venus's Wonderland

Barely contained within the decorative border of this painting is a fanciful cast of characters brought together from several different narratives. The biblical story of the serpent is reimagined here as a monkey tempting Eve to take a bite of the forbidden fruit. Eve is posed as Venus in Botticelli’s iconic painting The Birth of Venus, with the crocodile lying in her shell. Sikander’s use of animals to convey human traits is grounded in a collection of fables in the Persian illustrated manuscript tradition, Kalila wa-Dimna—itself a translation of the Panchatantra, an Indian fable collection written around the third century. Its story of the relationship between a crocodile and a monkey who lives in an apple tree is also referenced here.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Venus’s Wonderland, 1995–97

Watercolor and traces of graphite on tea-stained wasli paper

Rachel and Jean-Pierre Lehmann Collection

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Hood’s Red Rider No. 2

Cinderella’s prince holds her slipper at center while a powerful veiled heroine takes control above as a reimagined Red Riding Hood. Sikander explains, “European fairy tales, which carry deeply entrenched gender bias, were part of my childhood storybooks in Pakistan. When I started examining manuscript painting as a young adult, the passive depictions of women often perturbed me. I wanted to make female protagonists who were proactive, playful, confident, intelligent, and connected to the past in imaginative ways”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Hood’s Red Rider No. 2, 1997

Watercolor and gold paint on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Susan and Lew Manilow

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Cholee Kay Peechay Kiya? Chunree Kay Neechay Kiya?(What Is under the Blouse? What Is under the Dress?)

This work’s title is drawn from a song in the popular 1993 Bollywood film Khalnayak (The villain). In the scene in which the song plays, two women sensuously dance together while a man observes them. In Sikander’s response to the scene, the male figure has been left out.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Cholee Kay Peechay Kiya? Chunree Kay Neechay Kiya? (What Is under the Blouse? What Is under the Dress?), 1997

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Marieluise Hessel Collection, Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale- on-Hudson, New York

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: The title of this work references a song from a very famous Bollywood film. This was such a staple song in the 1990s. It was a mega hit song and also being performed at the parties and drag performances in queer spaces. So I didn't really start by creating an illustration of that song. It's just that the parallels started to emerge later. And when I was in conversation with the gender and sexuality scholar Gayatri Gopinath, who has written a essay in the book related to this exhibition, we started talking about how a queer optic can be used as a lens on reading so much of my work. And this reading that she brings to the work is really interesting to me as well, where she sees this gender and sexuality outside a conventional visual logic of secrecy and disclosure, invisibility and visibility. There is the body. The female body in this painting seems to exist in excess of gender itself. It sprouts limbs, lotuses, it endlessly repeats, doubles, multiplies, and then circles back on itself.

In Your Head and Not on My Feet

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

In Your Head and Not on My Feet, 1997

Graphite on paper

Collection of Susan and Lew Manilow

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Where Lies the Perfect Fit

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Where Lies the Perfect Fit, 1997

Graphite on paper

Collection of Susan and Lew Manilow

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Settling in New York

In 1997, as opportunities to show her work in New York expanded, Sikander decided to move there. She embarked on more ambitious installations of layered tracing-paper drawings, wall drawings, and projects combining the two. The speed and looseness of these large-scale works contrasted with the increasing refinement of her paintings. During a residency at Artpace, San Antonio, in 2001, she created her first animation.

In response to life in New York, Sikander continued to focus on female multiplicity and agency while also developing fresh concepts, especially after the events of 9/11, which affected her work deeply. “Questions of wealth and class, trade, global economics, race, and capitalism all started to percolate,” she said. “Negotiating a sense of belonging during this phase was riveting.”

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

The Many Faces of Islam

This piece was created for the New York Times Magazine feature “Old Eyes and the New: Scenes from the Millennium, Reimagined by Living Artists,” and was published in the September 1999 issue. The two central figures hold between them a piece of American currency inscribed with a quote from the Quran: “Which, then, of your Lord’s blessing do you both deny?” The surrounding figures speak to the shifting global alliances between Muslim leaders and American empire and capital. According to Sikander, “The 1990s was about war, coalitions, alternating friends and foes, imposed sanctions, debts forgiven, and human rights brushed under the carpet as America flexed its military muscle around the world. This work took this history into account, and I proposed that American policy in Islamic countries would become a defining issue in the new millennium.”

The portraits are, clockwise from upper left: Anwar Sadat; Menachem Begin; Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Pakistani singer of Sufi devotional music; Muhammad Ali Jinnah, founder of Pakistan; Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, president of Pakistan; Benazir Bhutto, prime minister of Pakistan; Malcolm X; Salman Rushdie; Nawal el Saadawi, feminist writer and physician, spokeswoman for the status of women in the Arab world; King Hussein; King Faisal; Asma Jahangir, Pakistani human rights lawyer and social activist; Hanan Ashrawi, spokeswoman for the Palestinian nation; Ayatollah Khomeini; Saddam Hussein.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

The Many Faces of Islam, 1999

Gouache, watercolor, gold leaf, and graphite, on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation II

This repertoire of forms and figures emerged during a period when Sikander was creating fifty to one hundred fast, gestural ink drawings each week. Suggestive forms were later given definition and supplied with appendages, typically using a marker pen. The resulting characters—often female, sometimes androgynous, sometimes monstrous—repeatedly enter her work, frequently as a collection of alter egos. According to Sikander, the figures address “the lack of female artists represented in art history and the art world and the misogyny women encounter in almost all spheres of work and life. The act of drawing became about converting erasure into opportunity through wit and candor.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation II, 1994/95

Ink on sketchbook pages

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: This is a time when I was reading and re-reading many texts by authors such as bell hooks, Audre Lorde, Angela Carter, Fahmida Riaz, Parveen Shakir, expanding my grasp of female poets and feminist forms, and in turn, exploring language from specific points in places of women's narratives. I was really keen to develop a lexicon of forms that could be both inventive and witty and could open up stories around gender and sexuality, forms that would sort of emerge from within, almost as if I had regurgitated them after perusing classical and historical South Asian sculptures and paintings. So for me, this process of locating a relationship to tradition was not to mimic, but to find a language that was connected to the research that I was doing, connected in a very natural manner. So I was kind of asking, "What is originality? How does one create something new?" The world is full of mysteries. There's always going to be a variety of distances between the real and the imagined. So I'm interested in history, I'm interested in politics, but I'm also interested in the dynamism of form, form as something alive and in conversation with its time, space, and language.

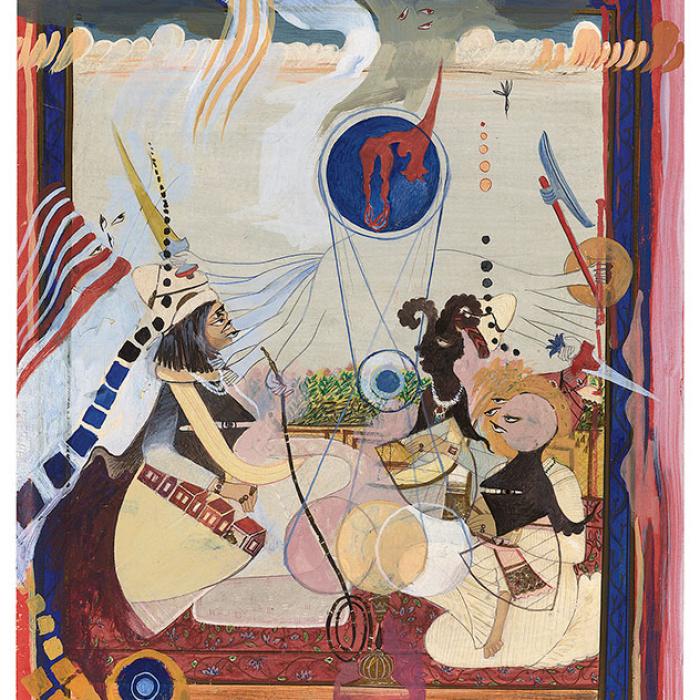

Mind Games

This scene is a restaging of the painting Jahangir Receives Prince Khurram from the imperial Mughal manuscript Padshahnama (Book of emperors), now in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Using the durbar hall as a compositional device, Sikander centers two self-portraits flanking a subway map, with rooftop water tanks in the top margin further signaling a New York City setting. In the lower register, courtiers from the historical painting—now wearing masks—gather, perhaps as witnesses of the past. Presiding at center is the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Sikander sees this deity as nonbinary and a symbol of multitude, with the ability to look in all directions and possess any form. She was intrigued with these chameleonlike powers and with masking as a metaphor for the many sides—some unseen—of any narrative.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Mind Games, 2000

Watercolor over inkjet print on tea-stained wasli paper

Courtesy of John McEnroe

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Riding the Ridden

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Riding the Ridden, 2000

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Niva Grill Angel

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

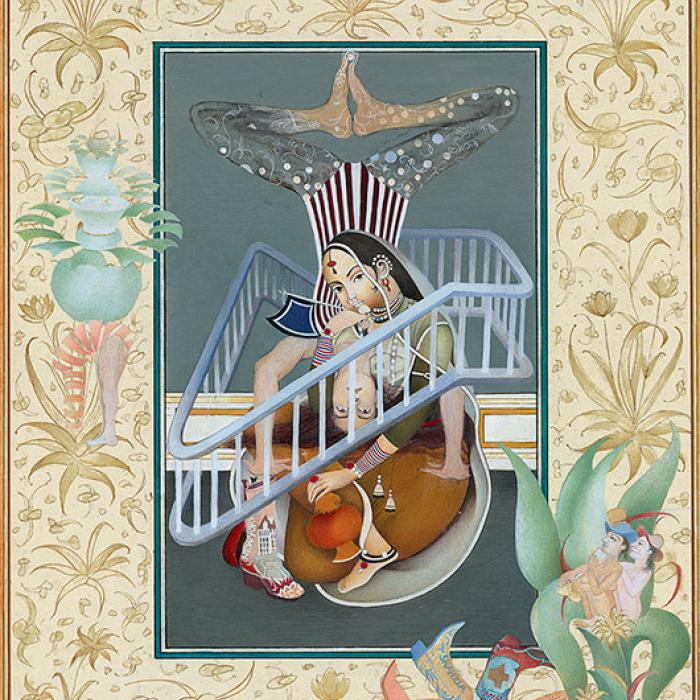

Elusive Reality

Two female figures meet at the center of this work. The seated woman is inspired by Deccani painting traditions that originated in Central India in the 1500s. The overlaid, upside-down portrait is of Sharmila Desai, an Indian dancer with whom Sikander worked closely in New York. Desai sometimes performed in spaces installed with Sikander’s drawings. Sikander photographed the dances and then incorporated select postures into her paintings.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Elusive Reality, 1989–2000

Watercolor and collage on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, New York

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: Working with another South Asian female and developing a collaborative practice, which allowed me to work with her where she choreographed many of pieces and performed in the drawings that I made. And then I brought her back into these small paintings, that dialogue that started to emerge was almost the strengthening of a South Asian feminine identity. So this is a time when being Asian American or Asian anything, one was questioning that paradox of being invisible while standing out. And what that broad racial category meant where so many different nations, ethnicities, classes, cultures, communities, languages had to vie to be recognized. So this work embodies that early period of developing a kind of collective identity with other South Asian artists.

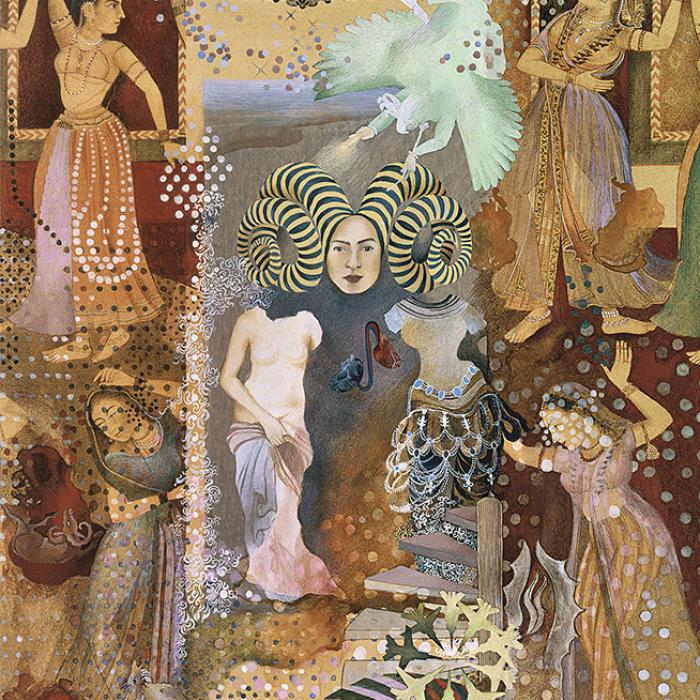

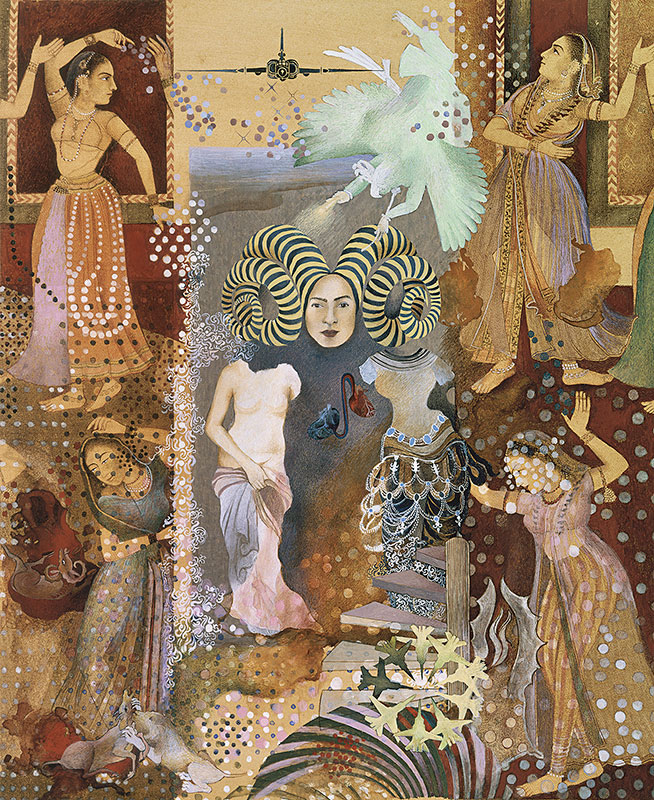

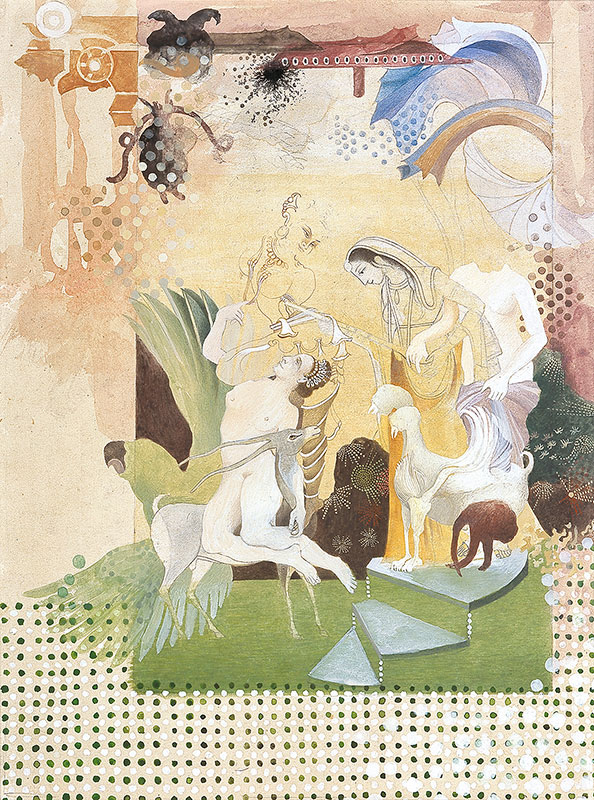

Pleasure Pillars

The array of archetypes portrayed here reveals the range of sources that Sikander looked to as she celebrated female sensuality and desire. Her central self-portrait with ram’s horns conjoins fragmented statues inspired by the Roman goddess Venus and a South and Southeast Asian celestial dancer. Above, two images of destruction threaten this scene of unrestrained pleasure: a fighter jet, which Sikander added in the aftermath of 9/11, and a winged, hybrid creature that seems to shoot fire from its hands.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Pleasure Pillars, 2001

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Amita and Purnendu Chatterjee

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: In this painting, there are multiple female references. So all these female avatars in my art have thoughts, emotions, feelings, and the iconographies are coming out of this vast intellectual virtuosic manuscript traditions of Central, South, and East Asia. There are a lot of syncretic layered visual histories that are usually referenced, and these women also embody a multidimensionality. And at times they may be androgynous, but they're complex and confident and proactive and also playful. That's what I wanted to celebrate in this particular work is the female sensuality, the desire as well as the courage. And it was a way of speaking back to the very fetishized female representations, especially at that time in 2001. I was countering the very paternalistic belief about saving of Muslim women from Islamic extremism, which was often used to justify the US imperial war and invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. So, this painting speaks back to some of that representation. You can see that the archetypes are gathered from multiple religious and cultural sources. There's this fighter jet under which even there's a portrait, which could be my self-portrait also.

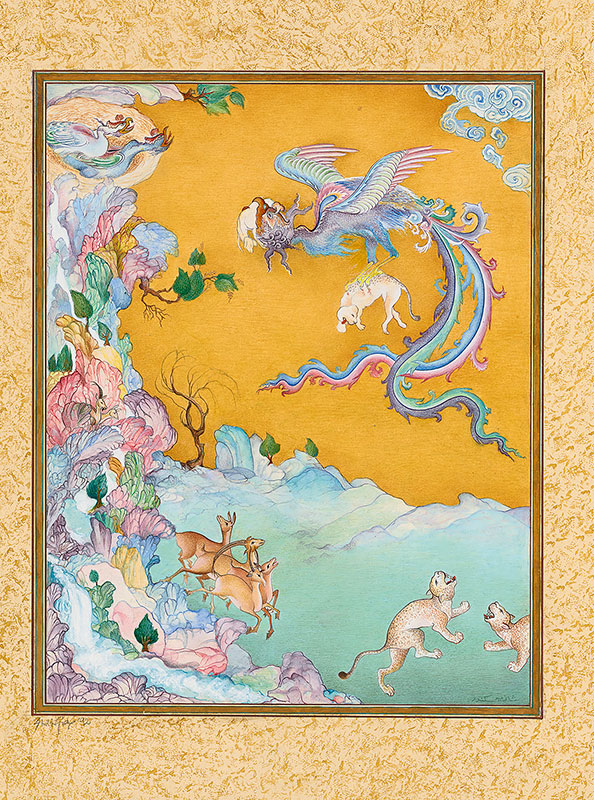

Sly Offering

The foundation for this work is Ascension of Solomon, a Safavid painting from the early 1500s now in the Freer Gallery in Washington, DC. Sikander disrupts the notion of sovereignty by removing King Solomon and handing the empty seat of power to her Indian and Greek female protagonists, who share or vie for control.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Sly Offering, 2001

Watercolor and inkjet outline on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Judy and Robert Mann

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: As in so much of my work here too, you can see the female protagonist rejecting the colonial, the male gaze. It is my intention to reimagine archetypal characters to tell richer stories. There's almost a back and forth a dialogue between historical paintings and languages, almost like an attempt to tell a story which operates very much like a poem, precise, as well as open-ended. I have a deep affinity with poetry as a catalyst, its ability to liven up language and to pack so much expression in a condensed form. When I look at this painting, I can read a bit of Adrienne Rich, I can read a bit of Solmaz Sharif in this work. And that's what I aim in my practice, is how to keep the work alive by adding many layers of meaning so that it can speak to multiple points of views. There's definitely a little bit of anarchy, a lack of sovereignty, and these constructions of femininity and beauty are all there as ways to dismantle perhaps orthodox representations. In this work, I think I was exploring what is a state of homelessness, not as in exiled or diasporic artist, but more as a collective female agency that could possibly rupture through abodes of patriarchy as well as militarism across national boundaries, cultures, and histories.

Intimacy

At center left in this work is an Indian celestial dancer modeled on a sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The dancer flirtatiously entwines herself around a figure taken from the sixteenth-century Italian Mannerist painting An Allegory with Venus and Cupid, by Agnolo Bronzino. Sikander created this pairing in response to Partha Mitter’s 1977 book Much Maligned Monsters: A History of European Reactions to Indian Art, which points to the role of cultural stereotypes in the European perception of Asia. At right is another pair of figures, sourced from Greco-Roman and Indo-Persian traditions. They stand arm in arm beside a two-headed creature, reinforcing multiplicity and suggesting the closeness and overlap of histories and cultures.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Intimacy, 2001

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Partial and pledged gift of Jeanne and Michael Klein, 2001

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

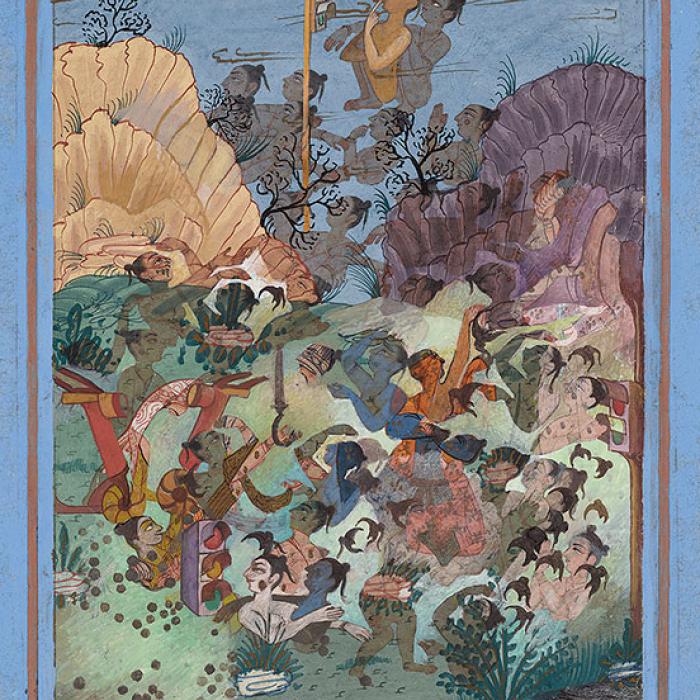

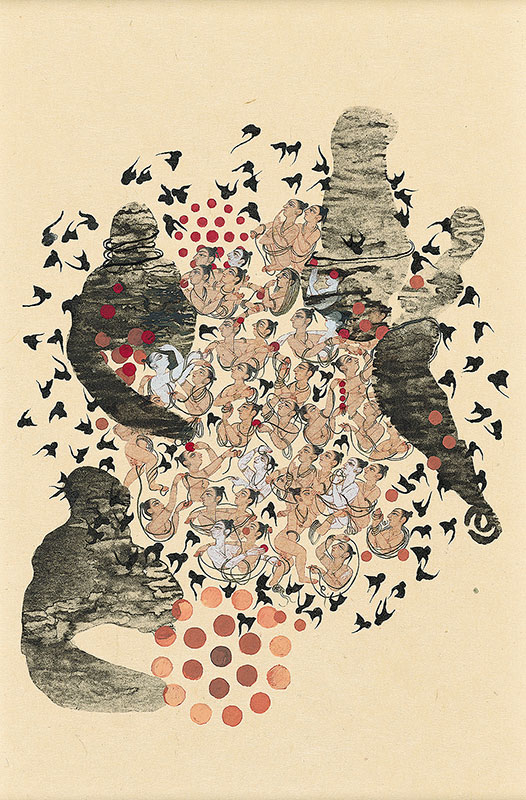

Gopi Crisis

The small female characters portrayed here derive from gopis, female cowherds and devotees of Krishna. Depicted from the waist up, they seem to be bathing, as they are often shown in Indian paintings. Large shadowy creatures—vaguely human, somewhat phallic— protect and contain the gopis, while bats or birds disperse from the center of the image. On close inspection, these flying forms are the hair of the gopis, detached and given life as a new symbol that will populate and animate Sikander’s work.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Gopi Crisis, 2001

Watercolor, gravure, inkjet, and chine collé, on tea-stained paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

From the series Monsters, Female Desires, and States of Dislocation

These uncanny forms interpret an array of objects, including swords, vessels, cannons, amulets, and masks—the types of images that might feature in Western coffee-table books on Islamic and Indian art. Sikander’s representations transform the inanimate objects into human-animal hybrids, imbuing them with agency. Her approach, she explains, was “an inventive and ironic play on the colonial histories of dispersing, rupturing, archiving, cataloguing, and institutionalizing art and artifacts of native cultures.” The distinct pattern created by the coagulation of ink on the sheets suggests reptile skin, ideal for rendering these subjects.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

From the series Monsters, Female Desires, and States of Dislocation, 2001

Ink on tracing paper

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Turmoil

This playful landscape scene features the female cowherds and devotees of Krishna known as gopis (also seen in several other paintings in the exhibition). Freed from previous restrictions, they seem ready to take on the world. At left are their scooters—not that they need them, as they seem capable of flying. They only have traffic signals to stop them.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Turmoil, 2001

Watercolor and inkjet on tea-stained wasli paper

Collection of Philip H. Isles

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

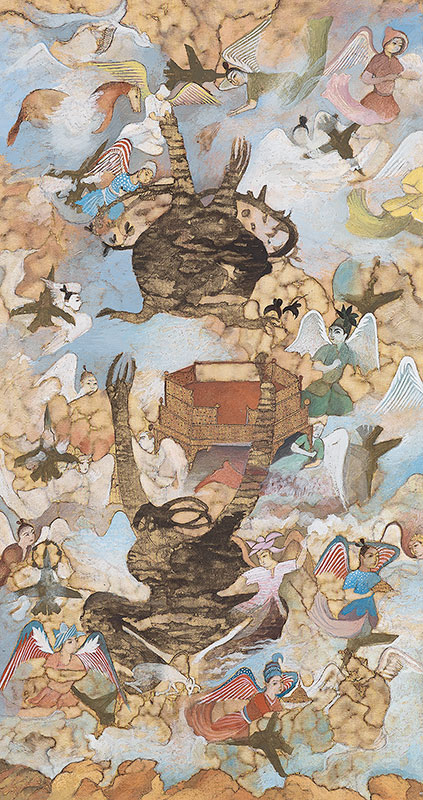

No Fly Zone

Sikander returned to the same Persian painting here that was the base for Sly Offering (on display nearby). Painted just as the United States was ramping up its response to the 9/11 attacks, No Fly Zone imbues the monstrous protagonists of Sikander’s early vocabulary with new political relevance. As scholar Sadia Abbas has noted, the empty throne in this painting—one of Sikander’s favorite motifs of the early 2000s—“marks a crisis of postcolonial sovereignty in an era of revived imperialism.” The jets and angels clad in red, white, and blue wings make clear the central role played by the United States.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

No Fly Zone, 2002

Watercolor, gravure, and inkjet outline, on wasli paper

Collection of Mitzi and Warren Eisenberg

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: In the center of this painting, you may recognize these ambiguous forms. If you look closely, they are evocative of the female body and they are anchoring the entire composition, even maybe disrupting a certain cosmic order of patriarchy, sovereignty. This work is a series that I did in the early 2000s when I was reflecting upon war, women and power, violence and capitalism, the drama of all these movements that are at the heart of a global crisis. There's also reference to many who are forced to migrate, the refugees, those from countries that are always on the no-fly list. As a Pakistani national, I was unable to travel outside of the US for more than eight years when my green card application was pending or lost in that abyss. So I was making also a statement on these questions of who controls power? How is that particular armature upheld? What is that space between the migrant and the immigrant, the citizen and the foreigner, how it's always in flux, a space where more and more communities are now defining that space on their own terms, and reflecting more of the complex, dynamic and evolving world that we all live in.

Web

The towers and aircraft in this painting call to mind the 9/11 attacks. The towers also suggest oil derricks, possible referencing the United States’ dependence on foreign oil, which was brought into question during President Bush’s impending invasion of Iraq. Heraldry links present-day policies to colonial- era exploitation. The large purse-like form is a lingam casket, which holds an amulet. The spiderweb is a reference to the one in a popular tale that shielded Muhammad from persecutors as he hid in a cave. The lush landscape with animals both nurtured and preyed on—copied from a Mughal manuscript painting—is the foundation of this composition filled with references to protection and destruction.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Web, 2002

Ink, gouache, gravure, and inkjet outlines, on tea-stained wasli paper

RISD Museum: Paula and Leonard Granoff Fund 2003.46

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Running on Empty

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Running on Empty, 2002

Watercolor and inkjet on wasli paper

Collection of Anika Rahman

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Segments of Desire Go Wandering Off

At the center of this painting, a multiarmed, uprooted female tries to hold on to all she desires—a chalawa (symbolizing impermanence), a turtle (symbolizing endurance), a floating child, a portrait of a woman, and a self-portrait of the artist. Sikander painted this figure over a large portrait of a trickster drawn by the Houston-based artist David McGee. All of the faces have been partly obscured, keeping racial and cultural identities shifting. As an immigrant, Sikander was questioning the prevalence of hyphenated identities in America and who is recognized as a citizen.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Segments of Desire Go Wandering Off, 1998

Collage with watercolor and graphite, on teastained wasli paper

Collection of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

The Pink Pavilion

Returning to a technique she first developed at RISD, Sikander created many multipart works, such as this one, on paper coated with a combination of clay, gesso, acrylic, and patching compound. More stable than tracing paper, this surface allowed her to precisely delineate the forms. Varying the amount of red clay provided a color range that Sikander likened to flesh tones. This textured, absorbent surface coaxed new characters and narratives from Sikander’s imagination. Tumbling, floating, and flying, the interacting figures are engaged in exuberant movement.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

The Pink Pavilion, 2002

Ink, opaque watercolor, and watercolor, on clay-coated paper

Collection of Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, New York

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: In my practice, drawing has a very central role. Drawing implies movement across time, across formats, across mediums. Drawing is a means of imagining and bringing ideas to life. So this series is a constellation of ideas. I see it as big ideas in small spaces, like a glimpse through the pages of a sketchbook. Many of the images seem to be in a joust, almost like a battle over each other. There's movement, both literal and symbolic, as in the crossovers between man and nature, human and animal, plant and animal, geometry and bodies, male and female. I don't see any particular beginning or an end in this work. You can start with any section, move left or right, up or down. Movement can be both literal as in the physical crossing of geographical borders, whether it's bodies, commodities, resources. But movement can also be symbolic, and that is the sense of belonging as where do you belong or what are you being excluded from? So that's a little bit of what this work is, that representations are not static.

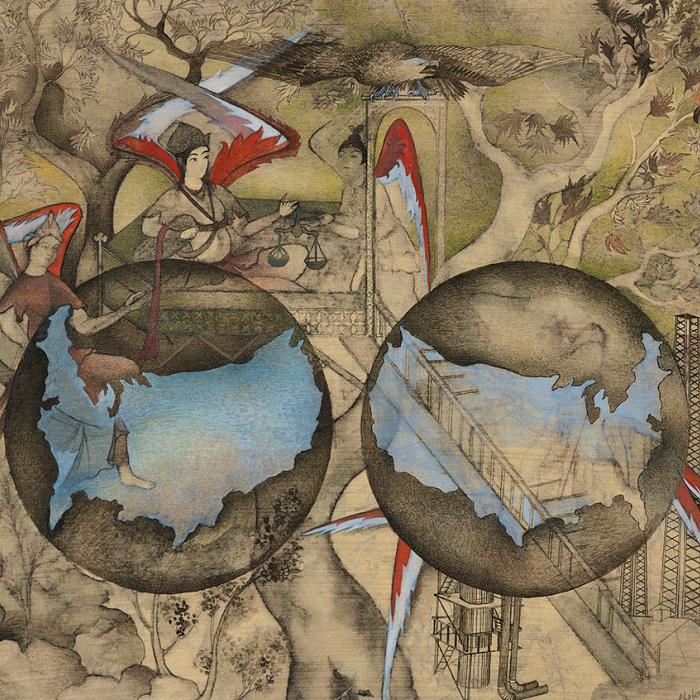

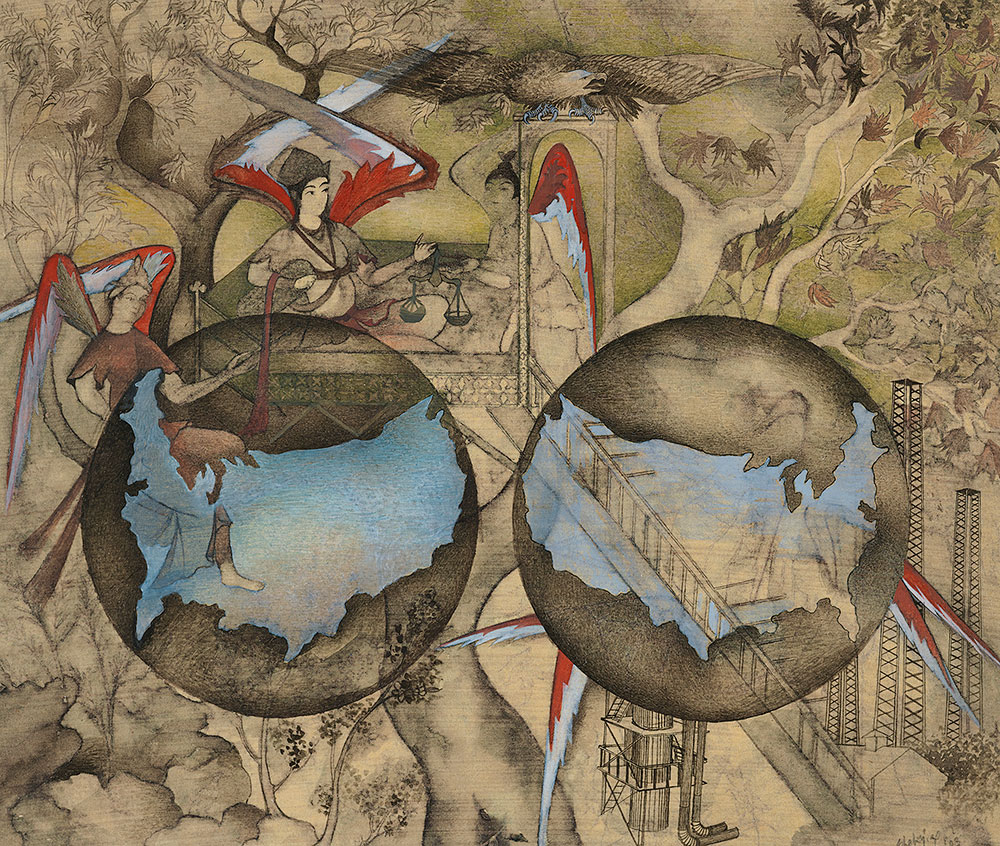

United World Corp

A detail from A Garden of Heavenly Creatures, a sixteenth-century Safavid painting in the Freer Gallery of Art collection, forms the backdrop for this work. In Sikander’s intervention, the garden has been overrun with an American presence. Globes featuring maps of the United States appear at center, an eagle reigns at top, and the angels have red, white, and blue wings.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

United World Corp, 2003

Watercolor and inkjet on wasli paper

Collection of Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, New York

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

SpiNN (III)

This painting, created for the animation SpiNN, includes several scenes of gopis in an act of rebellion. The gopis join together to create the beast that Krishna rides into the durbar hall. Once inside, they take over the space. Traditional Indian manuscript paintings typically feature only a single prominent gopi, Radha, the favored consort of Krishna. As Sikander multiplies the gopis’ numbers, she gives them all the agency of Radha, speaking to the power of a collective feminine space.

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

SpiNN (III), 2003

Watercolor on tea-stained wasli paper

Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Promised gift of Jeanne and Michael Klein in honor of Annette DiMeo Carlozzi, 2015

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: I started experimenting with animation in 2000. And it came very naturally to me in my process because I was always building layers in my paintings to create density and transparency. And sometimes there are more than 10 layers added into a single detailed small painting. So with that in mind, I thought I would register and document or scan every other layer of the painting as I built it. And that's where SpiNN emerges from, is it's in dialogue, in relationship to its painting, the counterpoint. And one of the most interesting shifts that happened in this work was when I painted the bodies of the female and then chose to eliminate them. But I wanted to retain some of their references in the work. So as they gather, their hair disassociates from their bodies. And that little element is small enough that it started to operate as a particle system. And I ran with that idea. So eventually, so much of the later animations are built up with the particle system in mind. And here you see the hair function almost like swarms or birds or bats or insects. And it can oscillate between a singular element, which is almost like the DNA of the feminine body. But then in its multiplication, it can also conjure up multiple different associations.

Epistrophe

In the late 1990s, the 2000s, and occasionally since, Sikander created installations of layered tracing-paper drawings, most often in combination with wall drawings, as a counterpoint to her painting practice. The intention was to use fluid, spontaneous gestures that involved her whole body and amplified her invented motifs. This large-scale work requires a different kind of labor, skill, and pace than her smaller, intricate compositions, but she still sees it as in dialogue with classical traditions. Sikander is also attracted to the openness of the piece: “There is no intention to hide anything,” she explains. “Everything is very visible; the paper is very transparent. It flows, it moves. All marks, including any flaws, become a part of the piece, which has no borders and can expand in any direction, marking a site that is unstable and multivalent.”

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Epistrophe, 2021

Gouache and ink on tracing paper

Collection the artist

The Morgan Library & Museum. Artwork © Shahzia Sikander, Photography © Casey Kelbaugh

Promiscuous Intimacies

Shahzia Sikander (born 1969)

Promiscuous Intimacies, 2020

Patinated bronze

Collection of the artist

© Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Pilar Corrias, London.

Shazia Sikandar: The two protagonists that you see in this sculpture are actually in my other paintings also, especially Pleasure Pillars and Intimacy. So you can recognize them there, but I wanted to call them out of the paintings and develop them into sculptures to see what would happen when these female bodies bear the symbolic weight of communal identities from across multiple temporal and geographic terrains. So I first sketched out these female characters in 2000 for a banner for MoMA when I worked with the curator, Fereshteh Daftari. At that time, I was just interested in art histories, classicism, and ethnocentric reactions to Indian art. But I was also making a point by entangling mannerism, the anti-classical impulse within the Western tradition alongside Indian art, both as accomplice witnesses of a one-sided history. But in 2017, I had the opportunity to be part of the New York City Mayor's Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers. And during that process, when I was hearing differing public opinions around public monuments, the complicated histories, a sort of a historical reckoning, and these tensions between communities regarding representation, at that time I felt that if I ever make a sculpture, I would make an anti-monument. And that's how I see this work, that it's not glorifying the past, but it is also evoking non-heteronormative desires that are often cast as foreign and inauthentic. And I want my sculpture to challenge the viewer to imagine a different past, present, and future where tradition, culture, identity can be seen as impure, heterogeneous, and unstable, kind of always in process where taken for granted boundaries and art, historical, and national temporal boundaries can be disrupted.