Morganmobile: Space

Now, where were we? In space, of course. Space in art might be deep, shallow, even intentionally flat. One hears space in an unvoiced bar of music, or within a complex chord. The distances in landscape can be rendered in a few precisely placed lines or the shifting hues of atmosphere. Space defines the margins of a page, the matrix in which dances are diagrammed—and even, in the modern age, the void through which visitors come flying to earth from somewhere far beyond.

Morganmobile: Space

Pieter Jansz Saenredam’s artistic career was largely devoted to so-called “church portraits”: images that meticulously describe ecclesiastical interiors. In this sheet, the artist’s subject is Haarlem’s Nieuwe Kerck (New Church), designed by his friend Jacob van Campen and built between 1645 and 1649. Over the course of the following decade, Saenredam returned to the church on numerous occasions, producing a series of drawings that explore the monumental building from a variety of viewpoints. In the absence of narrative details, the subject of these studies is the classically ordered and light-filled interior space of the Nieuwe Kerck itself.

Pieter Jansz Saenredam (1597–1665), Interior of the Nieuwe Kerk of Haarlem, 1650. Pen and brown ink and watercolor with red chalk over black chalk, 14 13/16 x 20 inches. Thaw Collection, 2010.108.

Morganmobile: Space

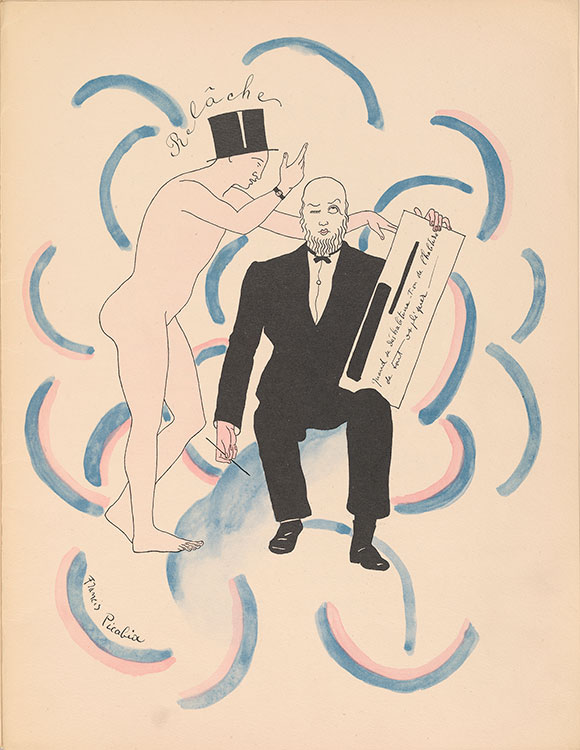

Francis Picabia, a collaborator on the 1924 ballet Relâche, illustrated the cover of Erik Satie's piano score with an encounter that appears to be set somewhere above the clouds. With the growth of the Dada movement after the First World War, the arts caught up with Satie’s anarchic spirit of play. Relâche is the word posted outside a theater when a performance is canceled, so the ballet's title suggests a gap where something substantial was expected. Instead of a clearly defined plot or characters, the premiere performance offered the audience a nonsensical array of half-dressed dancers, balloons, an absurd film between acts, and music adapted willy-nilly from ribald popular and military songs.

Erik Satie (1866–1925), Relâche; arr. piano, Paris: Rouart, Lerolle & Cie., [1926], first edition. James Fuld Music Collection, 2008.

Morganmobile: Space

In 1943, Aaron Siskind began pointing his camera at the graphic forms he found on city surfaces around him. In this photograph of peeling signage, fragments of the stenciled word “AREA” are just legible across the bottom of the picture. In a 1963 interview, Siskind explained that in his turn from social documentary to formal concerns, “I was operating on a plane of ideas. I was wiping out real space and somehow making you feel that the objects were forces so that there's a whole shift from description to idea, meaning.” Siskind’s elimination of perspectival space echoed the practice of Abstract Expressionist painters such as Franz Kline, his friend and fellow exhibitor at the Charles Egan Gallery.

Aaron Siskind (1903–1991), New York 6, 1951. Gelatin silver print, 17 7/8 x 14 inches. Gift of Richard and Ronay Menschel, 2015.56.

Morganmobile: Space

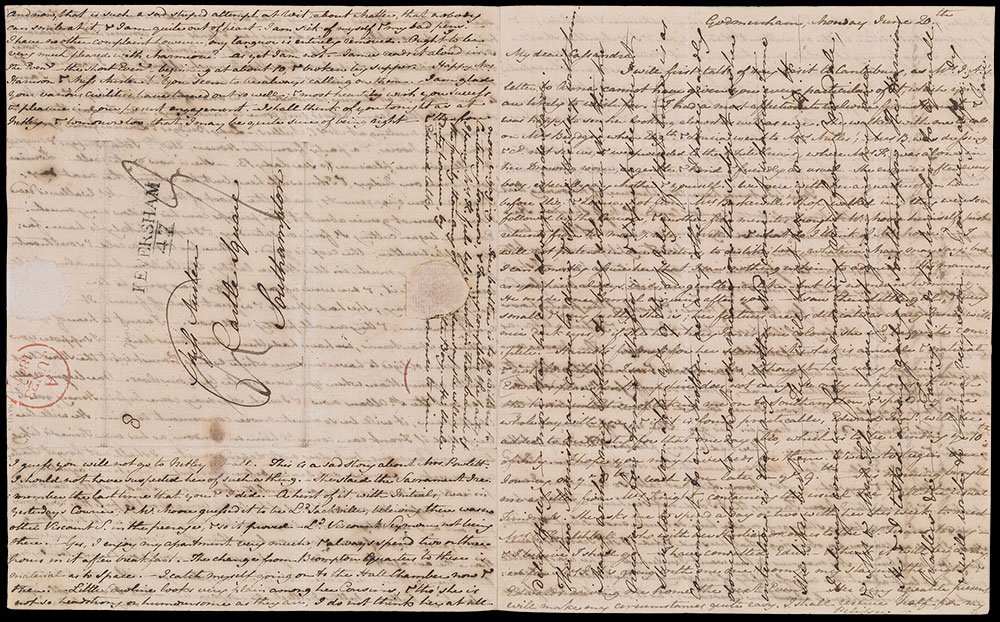

What happens when you’re writing a letter and you run out of space? Rather than starting a second sheet—which would have increased the postage charge—Jane Austen turned the paper ninety degrees to the right and began writing directly over her first page of text, creating a neat crosshatching of cursive. After writing the address in a blank space on the back of the folded sheet, she folded the letter into a small packet and sealed it with an adhesive disc called a wafer. No envelope was required. The letter made its way from Godmersham, where Jane wrote it, to Southampton, where her sister Cassandra received it, broke the seal, and read all her sister’s news.

Jane Austen (1775–1817). Letter to Cassandra Austen, Godmersham, 20 and 22 June 1808. Purchased by J.P. Morgan Jr. in 1920. MA 977.16

Morganmobile: Space

Colorful and creative line fillers offered medieval bookmakers an efficient way of enlivening their pages. The artist of this deluxe psalter clearly drew inspiration from the uneven spaces left behind by the lines of text. In page after page, his marginalia fill these gaps—sometimes naturally, as with the elephant, other times comically, as with the twisted and contorted figure below, who seemingly struggles to fit within his allotted space.

Text page from the Windmill Psalter, England, possibly London, ca. 1280–1300. MS M.102, fol. 162r. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1902.

Morganmobile: Space

A male figure stands before two altars, his hands raised in a gesture of worship. The first altar is decorated with a crescent moon, the symbol for the moon god, Sin, who was particularly venerated at Ur in southern Mesopotamia. On the second altar is the image of a dog, the sacred animal and symbol of Gula, the goddess of healing and patroness of physicians, who was favored and venerated at the Babylonian city of Isin. The rest of the seal surface is void of detail or decoration, leaving an empty space that focuses one’s attention on the worshiper, his act of piety, and the objects of his devotion.

Ancient cylinder seal with modern impression: Worshiper Before Two Altars Adorned with Divine Symbols. Mesopotamia, Neo-Babylonian period (ca. 1000–539 B.C.); lapis lazuli. Overall: 1 9/16 x 11/16 in. (3.9x 1.8 cm.) Morgan Seal 781. Acquired by Pierpont Morgan sometime between 1885 and 1908.

Morganmobile: Space

In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, one of the great triumphs of Flemish illumination was its playful manipulation of illusionistic space. In the area at the bottom of this scene, two figures appear to kneel before an image of the celebration of Mass. At the left, an angel, standing behind a lit Paschal candle, parts red curtains to reveal the image. Its frame, however, overlaps the angel’s wings, putting the image—contrary to expectation—in front of the angel as well as the two worshippers. Is the image truly meant to be read as a suspended painting? Or is it meant to be an actual celebration, which readers of the manuscript are permitted to see through a trompe-l'oeil opening in the page?

Mass of the Five Wounds of Christ, “Da Costa Hours,” in Latin. Belgium, Ghent, ca. 1515, illuminated by Simon Bening, MS M.399, fol. 36v. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1910.

Morganmobile: Space

Marsha Cottrell creates drawings by passing a sheet of paper repeatedly through a laser printer connected to a computer. Before each pass, she adjusts the size, placement, and tonality of rectangles on the computer screen to build up dense, layered images. She has described her process as “a random pattern of actions that is impossible to retrace.” In each work in this series, the final image presents a meditation on light and space, as if revealing an interior seen through a window from the outside.

Marsha Cottrell (b. 1964). Old Museum (Interior_7), 2015. Laser toner on paper; 9 3/16 x 11 5/8 inches (23.4 x 29.5 cm). Gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee; 2015.32

Morganmobile: Space

Edgar Degas was a regular presence at the popular, coarse entertainments that proliferated in late nineteenth-century Paris, notably outdoor café-concerts along the Champs Elysées. In this sheet he sought to recreate the experience of watching the famed chanteuse Emélie Bécat perform at night. To the foreground of an earlier lithograph depicting her onstage he added three women spectators in pastel. To their right he also extended the image with a vertical strip of paper, creating a third green pillar that presses against the picture plane. This deceptively simple addition brings the viewer into the scene, seated directly behind the women with a narrow view to Becat’s comic dance.

Edgar Degas, Mademoiselle Bécat at the Café des Ambassadeurs, 1877–1885; Pastel over lithograph on paper mounted on paperboard. Thaw Collection; 1997.88.

Morganmobile: Space

Dancing and court ballets were popular entertainments during the reign of King Louis XIV of France. Raoul-Auger Feuillet and Pierre Beauchamp (1631–1705) developed a notation system for choreography to record the steps and movements for both performance and social dances. This graphic notation records how the two dancers, Monsieur Blonde and Mademoiselle Victoire, moved around each other in the premiere of André Campra’s opera Tancrède in 1702. The principal lines signify where the dancers moved, while the shorter lines, curves, and hatch marks define movements of their feet and arms.

Raoul-Auger Feuillet (1659 or 1660–1710), Recüeil de dances (Paris: Chez le sieur Feüillet, 1704). Donated by Mrs. Jayne Wrightsman in honor of Mrs. Annette de la Renta; PML 198325.

Morganmobile: Space

This early drawing by Giovanni Battista Piranesi hints at the foreboding, seemingly irrational prison interiors he would design in later years. The diminutive size of the figures—probably added after the architecture was complete—distorts the sense of scale, and by showing the architecture at an oblique angle, Piranesi is able to suggest that the shadowy galleries extend almost indefinitely.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778). Perspective of massive piers and arches, ca. 1743–1744. Pen and brown ink and gray and brown wash, over black chalk; 7 3/16 x 9 11/16 inches (183 x 246 mm). Bequest of Junius S. Morgan and gift of Henry S. Morgan; 1966.11:16

Morganmobile: Space

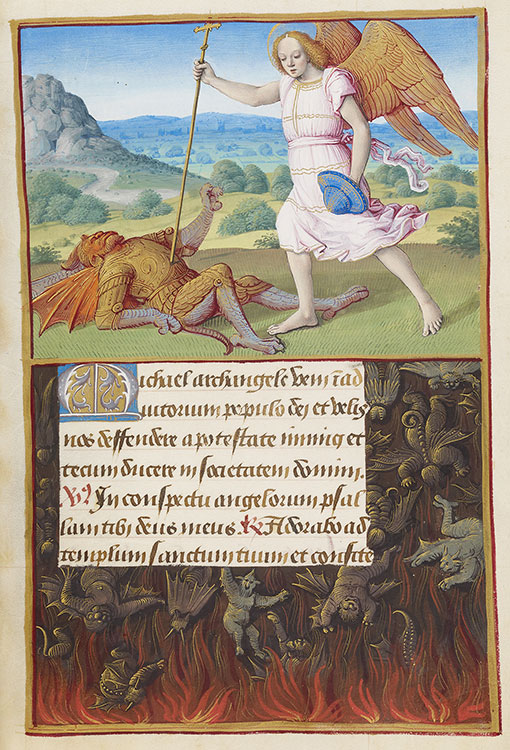

Casually brandishing his spear, an insouciant Saint Michael vanquishes the devil, effortlessly piercing Satan’s resplendent armor. The conflict occurs on a hilltop before a verdant landscape that recedes into the distance beneath a cloudless sky. The wide, unimpeded vista contrasts with the claustrophobic depths of hell into which the rebel angels plunge in the panel below. Using subtle gradations of color to modulate the scenery and create an illusion of depth, Jean Poyer demonstrates his mastery of atmospheric perspective, anticipating the rise of landscape painting as an independent genre.

St. Michael the Archangel battling the Devil, “Hours of Henry VIII”, in Latin. France, Tours, ca. 1500, illuminated by Jean Poyer, MS H.8, fol. 172r. Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977.

Morganmobile: Space

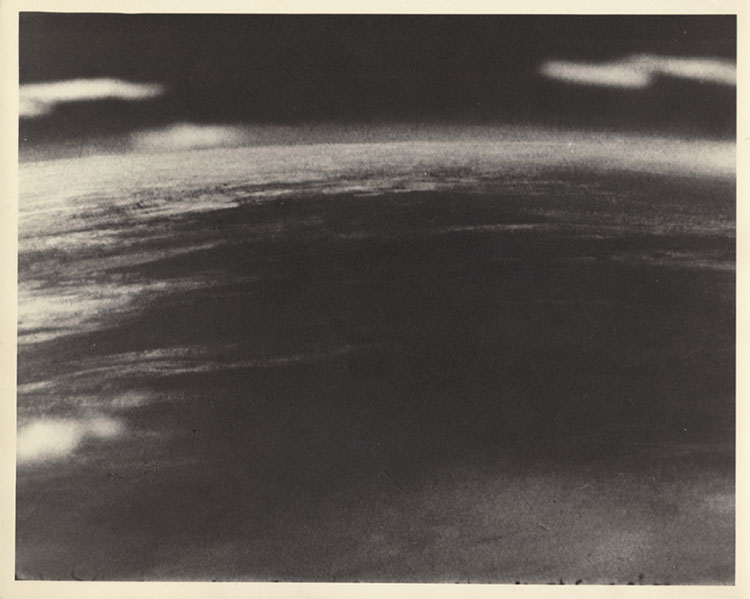

This image records the view from a rocket launched at White Sands Missile Range in 1946. An automatic camera in the nose cone exposed one frame of film every one and a half seconds, producing the clearest images up to that time of the curvature of the earth. A writer for National Geographic saw in the sequence “how Earth would look to visitors from another planet coming in on a space-ship.” The unseen back of this print hints at another journey: the migration of “outer space” from the realm of military research into that of science fiction. The print, formerly owned by a Hollywood film studio, is inscribed “Riders to the Stars”—a 1954 feature film whose heroes fly into orbit to battle a meteor swarm.

Earth from the Thermosphere, made by a camera attached to a V-2 Rocket, 1946. Gelatin silver print, 7 1/2 x 9 1/2 inches. Purchased on funds given by the Margaret T. Morris Foundation and by Richard and Ronay Menschel, with special assistance by Daniel Blau, 2020.83