Édouard Vuillard: Sketches and Studies

From his participation in the Parisian avant-garde of

the 1890s to the large mural decorations he created in the first decades of the twentieth century, Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940) played an important role in French modern art. Although better known for his paintings, Vuillard drew extensively throughout his life, largely in the pages of sketchbooks, which he kept in the privacy of his studio. Most of these sketches were made from direct observation and served as the basis for paintings.

After his death, Vuillard’s sketchbooks were often taken apart. Through the generous gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig, the Morgan recently acquired fifteen of his drawings, which are the subject of this exhibition. Covering the artist’s entire career, they range from quick sketches to more elaborate studies. As a whole, they give a tantalizing overview of Vuillard’s drawing practice. The exhibition also features the gift of Jill Newhouse of a pastel study for one of Vuillard’s last decorative commissions: a painting adorning the Palais de Chaillot theater in Paris.

Overview

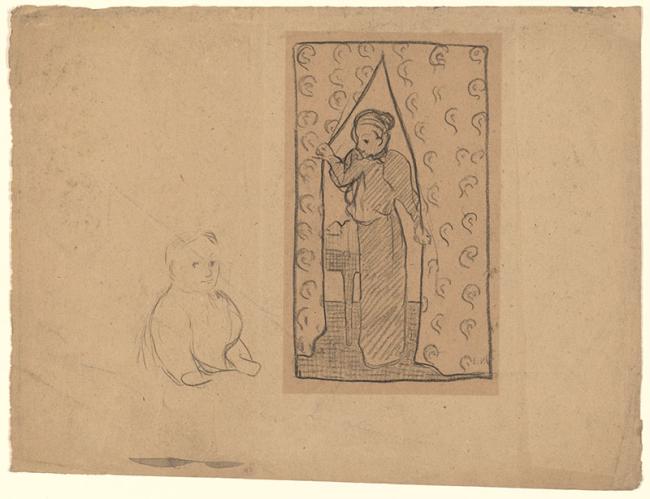

Young Woman Parting a Curtain

The curtain motif links two worlds central to Vuillard’s life during the 1890s: his home environment and the theater. An abundance of patterned fabrics typically dominates his depictions of the house he shared with his mother and sister, both seamstresses. In this drawing, the woman with her hair in a chignon resembles Vuillard's sister and the piece of furniture behind her evokes a domestic setting; yet the scene also recalls a theater program Vuillard designed around the same time featuring a character emerging from behind a stage curtain.

Vuillard made this sketch on part of a larger sheet that, for over forty years, was folded and framed in such a way as to hide most of its surface—hence the darkening of the exposed section.

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

Young Woman Parting a Curtain, ca. 1893

Black chalk on light brown paper

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.278

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Theater Box

The theater box, where people went to be seen as much as to watch a performance, was a common subject in late nineteenth-century French painting—for instance in the work of Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec. Here, Vuillard directed his attention to the profile of a man he depicted twice, once in the box and again at the bottom of the page. An inscription on the sheet’s verso identifies him as Arthur Meyer (1844–1924), the director of the conservative, anti-Republican daily newspaper Le Gaulois (The Gaul). An avid theatergoer, often seen in the company of beautiful actresses, Meyer was frequently caricatured in the liberal press.

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

The Theater Box, ca. 1905

Graphite on page removed from a sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.279

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Bowl on the Table

Vuillard painted few still lifes per se, but he included exquisite ones within depictions of family and friends at the breakfast or dinner table. In these works, objects often play a symbolic or metaphorical role, mirroring by their relative size or placement psychological tensions among the protagonists. Thus Vuillard may have planned to use this bowl, precariously positioned, off-center on the plate, to signal that something was amiss in the seemingly harmonious scene. In Vuillard’s domestic interiors, drama often lurks behind the elegant crockery.

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

The Bowl on the Table, ca. 1905

Graphite on page removed from a sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.280

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

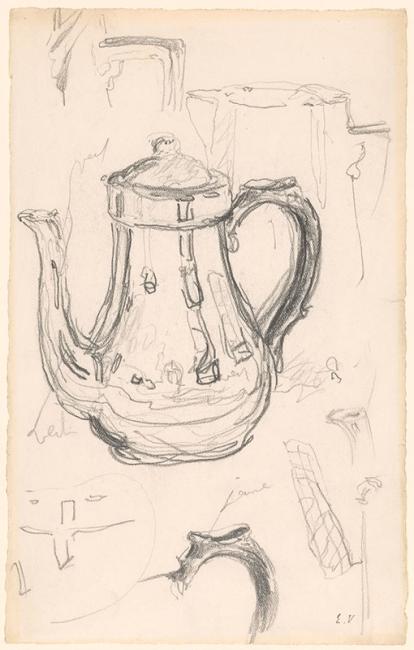

The Coffee Pot

Vuillard typically painted from memory, using his sketches as aide-mémoire. “I have enough to keep me busy for years on end developing and making artworks out of everything I have in my sketchbooks and folders,” he once wrote in his journal. A coffeepot resembling the one in this study appears in several of his pictures of breakfast tables. Vuillard’s intention to use the sketch for a painting is evident from the color notations inscribed on the sheet: vert (green), written twice next to the spout, and jaune (yellow), by the detail of the handle at the bottom of the page.

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

The Coffee Pot, ca. 1920

Graphite on paper

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.289

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Table in Front of the Window

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

The Table in Front of the Window, ca. 1910

Graphite on page removed from a sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.282

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

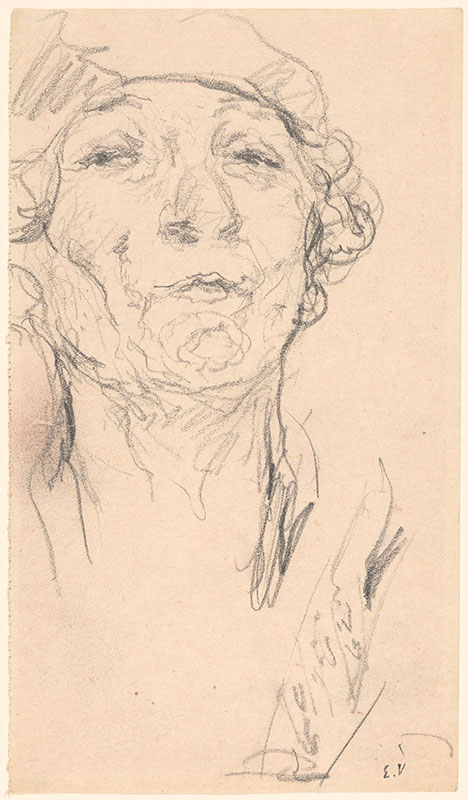

Attentive Face

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

Attentive Face, ca. 1920

Graphite on page removed from a sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.286

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Young Woman Seated on a Sofa

“I don’t make portraits,” Vuillard once declared, “I paint people at home.” No painting is known to correspond to this sketch, which shows a typical “portrait” as Vuillard conceived of them: more space and attention is devoted to the furniture and objects surrounding the sitter than to the figure herself. The aim was to capture his subject’s personality through a detailed evocation of her environment. During the last twenty-five years of his life, Vuillard’s notoriety rested primarily on such portraits, which were highly sought after by members of the Parisian uppermiddle class.

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

Young Woman Seated on a Sofa, ca. 1920

Graphite on page removed from a sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.287

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Kiosk, Place Saint-Augustin

This sketch is one of many studies Vuillard made in preparation for two large decorative panels he painted in 1912−13 depicting the Place Saint-Augustin, a city square in Paris’s eighth arrondissement. Keen on showing a modernized Paris, the artist included new features of city life such as streetcars in the paintings. Here, he focused his attention on a Morris column, one of the cylindrical kiosks installed throughout the city beginning in the 1860s to display advertising, especially for theater and concerts.

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

The Kiosk, Place Saint-Augustin, ca. 1912

Graphite on page removed from sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.283

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

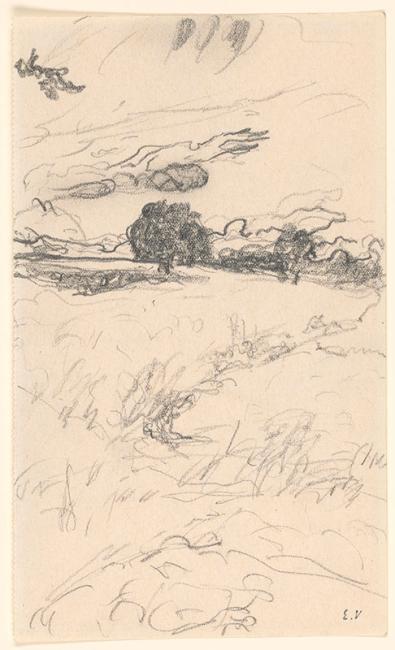

Large Tree in the Distance

While Vuillard devoted most of his early career to interior scenes, around 1900 he began to discover the pleasure of drawing outdoors. “I really enjoy being in the country,” he wrote that year. “I’m astonished to see the sky, by turns blue, grey, green, and that the clouds come in all sorts of different shapes and colors.” Although Vuillard rarely painted pure landscapes, his numerous sketches of trees, such as this one, became inspiration for the backdrops of large-scale decorations depicting gatherings in the countryside.

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

Large Tree in the Distance, 2019.281

Graphite on page removed from a sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.281

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Tree at Gérardmer

Toward the end of the First World War, Vuillard was commissioned by the French government to record life at the front. He was sent to Gérardmer, a town in the Vosges area, near the German border. Harboring anti-military feelings, Vuillard had no interest in glorifying soldiers in battle and may have found relief in sketching this tree with a view of the town beyond.

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

Tree at Gérardmer, 1917

Graphite on page removed from a sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.284

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

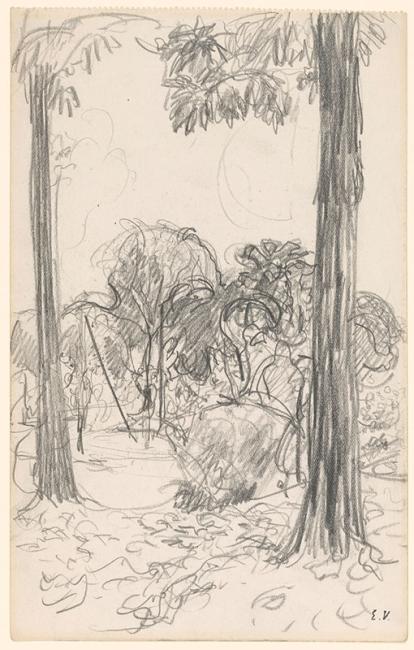

Garden

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

Garden, ca. 1918

Graphite on page removed from a sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.285

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Rooster

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

The Rooster, ca. 1926

Graphite on page removed from a sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.29

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Corner of the Garden

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

Corner of the Garden, ca. 1920

Graphite on page removed from a sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.288

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

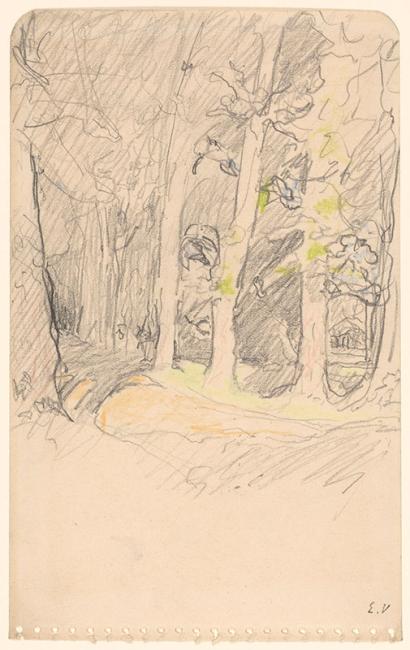

Large Trees

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

Large Trees, ca. 1928

Graphite and pastel on page removed from a spiral-bound sketchbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.291

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Château des Clayes

In 1925, Vuillard’s dealer Jos Hessel and his wife, Lucy, bought the Château des Clayes, a country estate near Versailles, about fifteen miles west of Paris. A frequent guest, Vuillard had his own room in the château and spent increasingly long stretches there during the last twelve years of his life. Both the château’s interior and exterior, with its characteristic round tower, inspired many drawings and paintings, as did the expansive surrounding park. After Vuillard’s death, during World War II, Les Clayes was requisitioned by the Nazis and subsequently burned and mostly destroyed by German troops at the end of the war.

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

Château des Clayes, ca. 1930

Graphite on page removed from a spiral-bound skechbook

Gift of Mary Jo and Sheldon Weinig; 2019.292

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Study for La Comédie of the Palais de Chaillot

In 1936, Vuillard was commissioned to provide a decoration on the theme of comedy for the entrance to the newly built Théâtre national de Chaillot in Paris. Setting the scene on the grounds of the Château des Clayes, he composed the vast painting like a stage. In the foreground, at left, are characters inspired by Molière—a marquis seducing an ingénue, perhaps from The Misanthrope; and at right, Titania and the donkeyheaded Bottom from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The final painting, still in place at the theater, is over eleven feet wide, showing Vuillard’s talent for developing monumental compositions from very small sketches.

Édouard Vuillard

1868–1940

Study for La Comédie of the Palais de Chaillot, 1936–37

Pastel and graphite on paper

Promised gift of Jill Newhouse; 2020.98

© Édouard Vuillard / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York