Portraits for a New Millennium

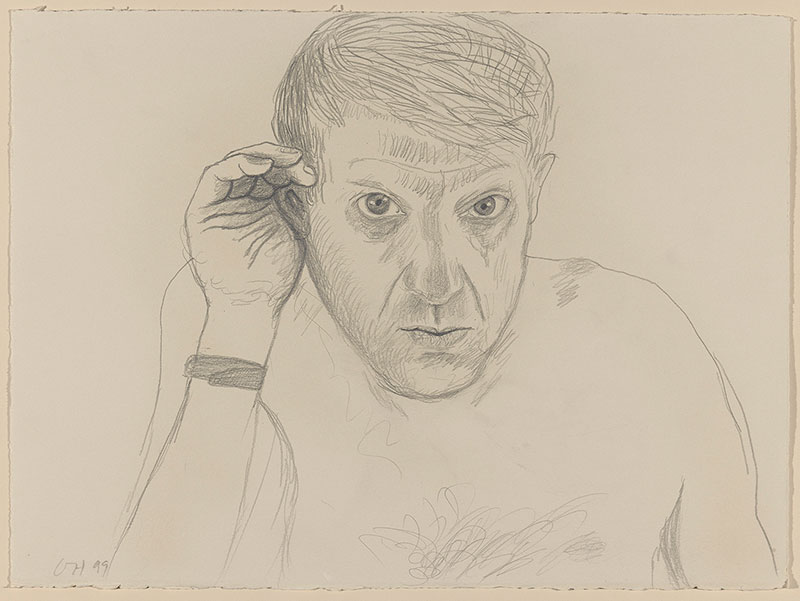

In the 1980s, while he experimented with neo-Cubist distortions in his paintings, Hockney continued to make traditional drawings as a means of looking inward. In the autumn of 1983, he produced a series of contemplative self-portraits in which he observed himself, as a middle-aged man, with honesty and vulnerability. “I just thought I’d look at myself. As I go deafer, I tend to retreat into myself, as deaf people do,” he explained. In another self-portrait series, executed in 1999, he adopted a more playful attitude in a range of facial expressions.

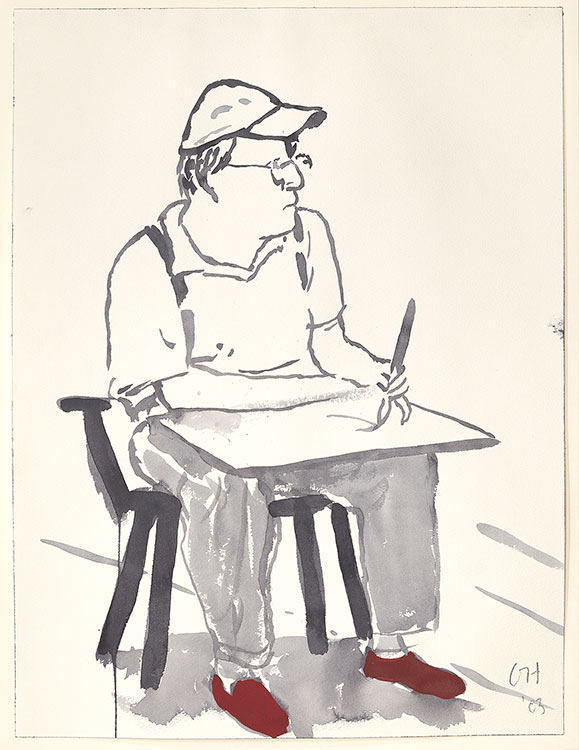

A few years later, Hockney turned to watercolor, a medium he had not explored since the 1960s. This new way of working freed up his approach, allowing him to draw quickly and directly on paper. He described these watercolors as “portraits for the new millennium,” convinced that, despite his experimentation with photography and other technologies, the human eye and hand were still the best tools for capturing the individuality of his sitters.

Artwork: © David Hockney

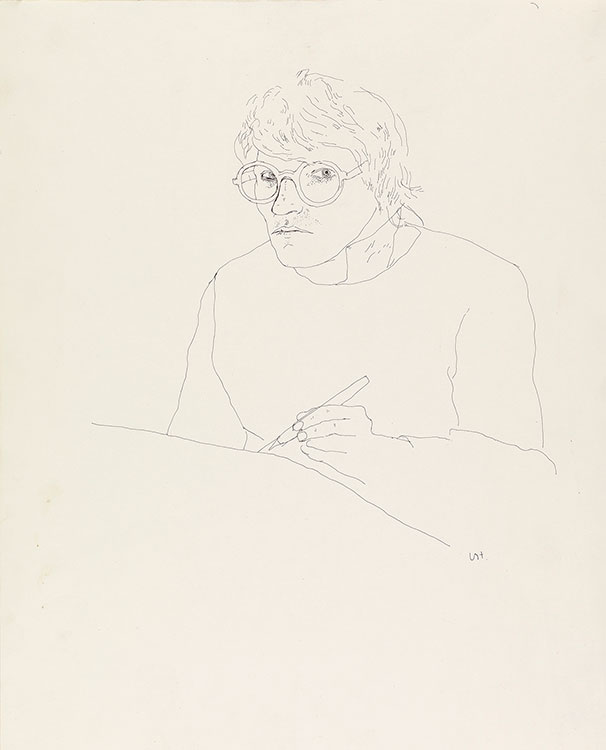

Self Portrait with Pen

David Hockney

Self Portrait with Pen, 1969

Ink on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self Portrait, 1980

David Hockney

Self Portrait

1980

Lithograph

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney / Gemini G.E.L.

Photography by Richard Schmidt

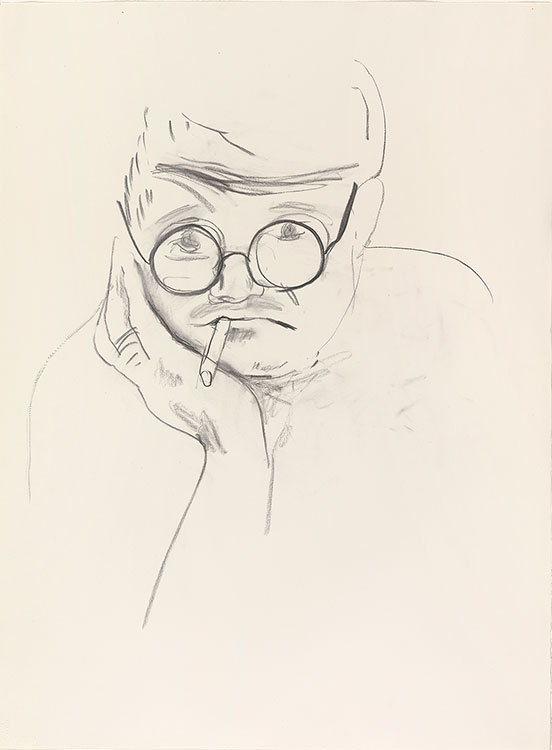

Self Portrait with Cigarette, 1983

David Hockney

Self Portrait with Cigarette, 1983

Charcoal on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

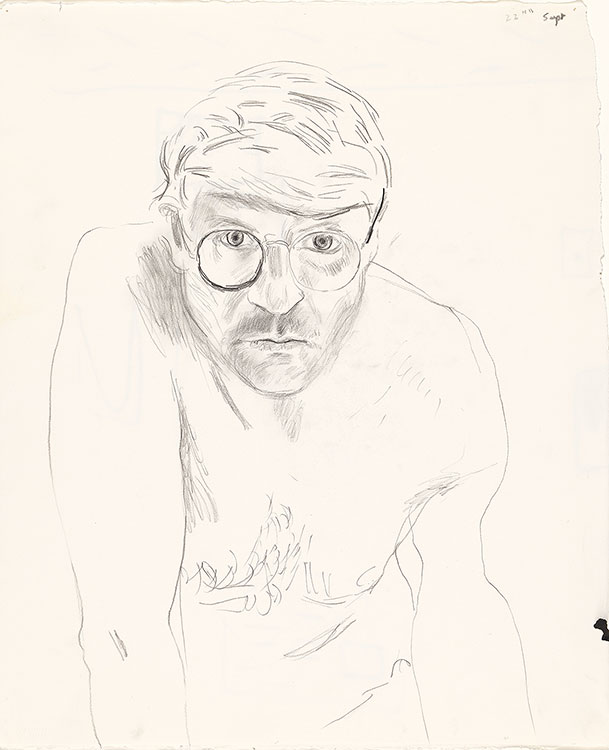

Self-Portrait, 22nd Sept. 1983

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 22nd Sept. 1983, 1983

Charcoal on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self Portrait 26th Sept. 1983

David Hockney

Self Portrait 26th Sept. 1983, 1983

Charcoal on paper

The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

© David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 30 Sept 1983

In the autumn of 1983, almost every day for two months, Hockney challenged himself to produce a candid self-portrait in charcoal. This period of intense self-reflection was, in part, a reaction to the untimely deaths of many of his friends due to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The vulnerability exposed in these drawings is a far cry from the confident self-portraits of thirty years earlier. Like the pages of a diary, these works record daily changes in the artist’s moods and emotions.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 30 Sept 1983, 1983

Charcoal on paper

Collection National Portrait Gallery, London

© David Hockney

Photography by Fabrice Gibert

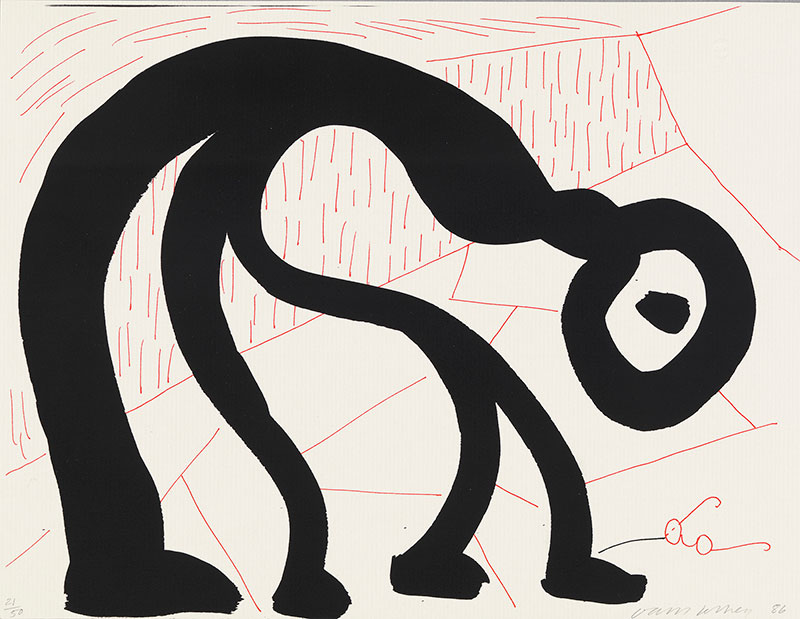

Man Looking for His Glasses

David Hockney

Man Looking for His Glasses, April, 1986, 1986

Homemade print

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

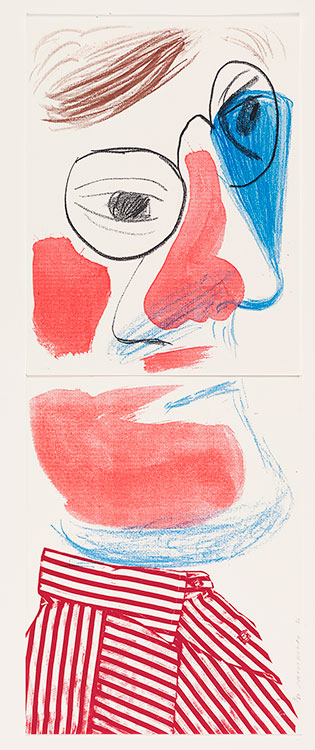

Self-Portrait, July 1986

In 1986, while working on designs for a production of Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde, Hockney began experimenting with a color laser photocopier to produce what he called "home-made prints." Replicating the traditional printmaking process, he repeatedly fed a single sheet of paper through the copier until each color of the drawing had been printed. In this self-portrait, he even placed his own striped shirt on the glass plate of the copier. Though created with modern technology, the prints have a playful directness that reveals the artist’s hand.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, July 1986, 1986

Homemade print on two sheets of paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Polaroid of Self-Portrait Drawing and Glasses (1–6)

David Hockney

Polaroid of Self-Portrait Drawing and Glasses (1–6), 1987

Polaroid

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 1988

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 1988

Crayon on sketchbook page

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self-Portrait (Earthquake), Jan. 17, 1994

The inscription on this sheet explains the artist’s weary look. Hockney, who lived in Los Angeles at the time, drew this self-portrait on the day the powerful Northridge earthquake struck the San Fernando Valley, northwest of the city—one of the most devastating earthquakes in United States history.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait (Earthquake), Jan. 17, 1994, 1994

Crayon on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self-Portrait, London, 3rd June 1999

Hockney has always made candid self-portraits in moments of introspection, tracking his own aging process. These playful drawings in which he displays different facial expressions, influenced by Rembrandt’s self-portrait etchings, can be seen as precursors to the iPad self-portraits.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, London, 3rd June 1999, 1999

Pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Steve Oliver

Self-Portrait, Baden-Baden, 10th June 1999

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, Baden-Baden, 10th June 1999, 1999

Pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self-Portrait, Baden-Baden, 10th June 1999

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, Baden-Baden, 10th June 1999, 1999

Pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self-Portrait, March 2 2001

The presence of the mirror frame in this drawing recalls a typical composition of Renaissance portraits in which the sitter is shown beyond a window ledge. Inspired by the extensive research he was conducting at the time into old master methods—notably the use of lenses and mirrors—Hockney adopted here the classical bust-length pose that is found in portraiture throughout European art history.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, March 2 2001, 2001

Charcoal on paper

Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle. Purchased 2002 [am2002-281]

Françoise and Jean Frémon, Paris

© David Hockney

Self-Portrait Using Three Mirrors

David Hockney

Self-Portrait Using Three Mirrors, 2003

Watercolor on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

'True Mirror' Self-Portrait II

David Hockney

‘True Mirror’ Self-Portrait III, 2003

Ink and watercolor on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self Portrait with Red Braces

David Hockney

Self Portrait with Red Braces, 2003

Watercolor on paper

Collection Gregory Evans

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self-Portrait, 17 Dec. 2012

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 17 Dec. 2012, 2012

Charcoal on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

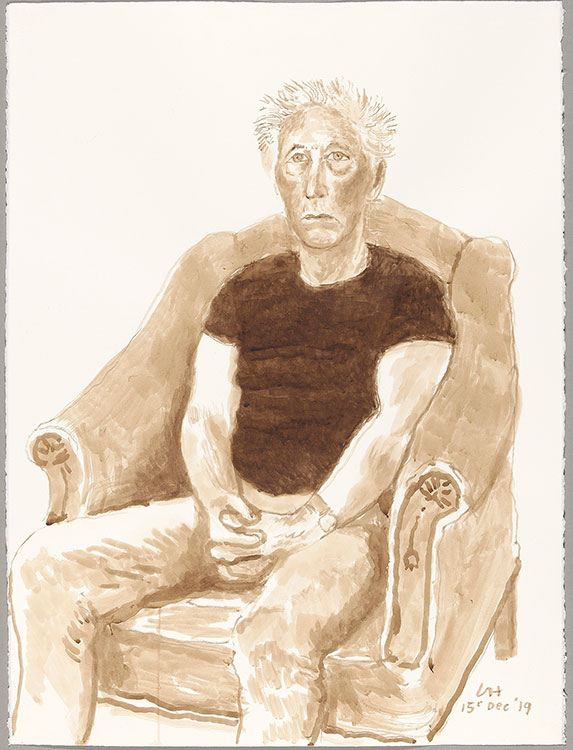

Recent Portraits of Gregory, Celia, and Maurice

In the spring of 2019, Hockney traveled to Amsterdam for the opening of Hockney – Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature, an exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum. While there, he fell in love with Rembrandt again. Later that year, with Rembrandt and Van Gogh on his mind, and spurred by the prospect of the present exhibition, Hockney invited Celia, Gregory, and Maurice to sit for a new drawing series. In these three-quarter-length portraits, he paid particular attention to faces and hands, often his starting point. Drawn in Los Angeles and Normandy, where Hockney had recently moved, the portraits are fond evocations of time spent together and represent the many familiar faces and expressions of his old friends. Using Japanese brushes with integral reservoirs and the walnut-brown ink favored by Rembrandt, Hockney achieved an uninterrupted line and built up the portraits in three different tones.

Gregory Evans I

David Hockney

Gregory Evans I, 27 June 2019, 2019

Ink on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Maurice Payne, 16th Dec 2019

David Hockney

Maurice Payne, 16th Dec 2019,

Ink on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Gregory Evans II

David Hockney

Gregory Evans II, 27 June 2019, 2019

Ink on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Celia Birtwell

David Hockney

Celia Birtwell, Nov. 21 2019,

2019

Ink on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Jonathan Wilkinson

Maurice Payne, 15 Dec 2019

David Hockney

Maurice Payne, 15 Dec 2019, 2019

Ink on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt