The Artist’s Mother

The large number of portraits Hockney made of his mother attests to the close bond between them. A devout Methodist and strict vegetarian, Laura Hockney (1900−1999) raised her four children with great generosity of spirit. Supportive of her son David’s desire to be an artist, she remained a loyal and patient model who would always sit still for him.

Although Hockney is critical of photography— “A photograph cannot really have layers of time in it the way a painting can, which is why drawn and painted portraits are much more interesting,” he once said—the large portrait that dominates this section was made from photographs. In 1982, Hockney began creating collages with Polaroid prints, which he worked into grids. He eventually went on to create more complex images with irregular edges using 35 mm photographs, such as this portrait of his mother. The influence of Picasso and Cubism is evident in these works, in which he captures simultaneous viewpoints and a narrative that reflects the passage of time. Hockney compared the photocollage pro- cess to a kind of drawing: “I felt these pictures were linear, and that in piecing them together, picture by picture, I was really drawing line, linking them.”

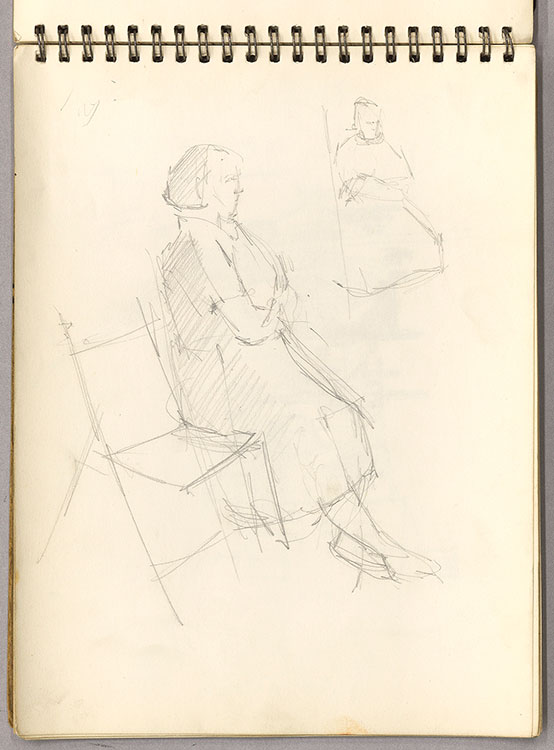

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook)

David Hockney

David Hockney

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), 1953, Page 4

Pencil, ink and wash

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook)

David Hockney

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), 1953, Page 48

Pencil, ink and wash

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), Page 3

David Hockney

David Hockney

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), 1953, Page 36

Pencil, ink and washon

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), Page 52

David Hockney

David Hockney

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), 1953, Page 52

Pencil, ink and wash

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), Page 56

David Hockney

David Hockney

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), 1953, Page 56

Pencil, ink and wash

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Mother, Paris

David Hockney

Mother, Paris, 1972

Colored pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Study for "My Parents and Myself"

While Hockney was living in Paris intermittently from 1973 to 1975, he was visited by his parents and began making preparatory drawings for a painting of them. His father worked as a clerk but was also an amateur artist and antismoking campaigner, well known for his strong political views. His mother was a quiet but strong matriarchal figure. The artist inserted himself into the picture through his reflection in the mirror on the cart.

David Hockney

Study for “My Parents and Myself,” 1974

Colored pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Mother, Bradford. 19 Feb 1979

Hockney made this drawing on 19 February 1979, the day of his father’s funeral. When he signed and dated it later, however, he mistakenly inscribed the year 1978. Relying on a minimal line, the artist conveys the sadness in his mother’s face as she looks directly at her son. The use of sepia ink applied with a reed pen—a possible reference to Van Gogh— gives his mother a softer, more vulnerable air than in the earlier pen-and-ink portraits. Making a drawing was less intrusive than taking a photograph would have been. Drawing had become Hockney’s way of communicating with his mother.

David Hockney

Mother, Bradford. 19 Feb 1979, 1979

Sepia ink on paper The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt