David Hockney: Drawing from Life

David Hockney (b. 1937) is one of the master draftsmen of our times. Drawing lies at the heart of his studio activity and has consistently underpinned his work. From early pen-and-ink drawings and photocollages to more recent experiments with watercolor and digital technology, Hockney’s inventive visual language has taken many stylistic turns. Inquisitive, playful, and thought provoking, his drawings reflect an admiration for both the old and modern masters, from Rembrandt to Picasso.

Drawing from Life explores Hockney’s record of encounters with those close to him. Portraits of family and friends show the artist’s mother, Laura Hockney; textile designer Celia Birtwell; his friend and former curator Gregory Evans; and printmaker Maurice Payne. Also featured is a large selection of self-portraits. By focusing on Hockney’s intimate and revealing depictions of five people dear to him, the exhibition charts the effect of the passage of time—on his sitters and his relationship to them, and on the development of his style over the last seven decades.

This online exhibition was created in conjunction with the exhibition David Hockney: Drawing from Life on view October 2, 2020 through May 30, 2021.

![]() The exhibition is organized by the National Portrait Gallery, London, in collaboration with the artist and the Morgan Library & Museum.

The exhibition is organized by the National Portrait Gallery, London, in collaboration with the artist and the Morgan Library & Museum.

The New York presentation is made possible by Mr. and Mrs. Robert King Steel and Katharine J. Rayner. Additional support is provided by the Rita Markus Fund for Exhibitions, with assistance from Dian Woodner and David and Tanya Wells.

Overview

Portrait of the Young Artist

David Hockney was born on 9 July 1937 in Bradford, West Yorkshire. As a schoolboy, he had a passion for art even before he fully understood what it meant to be an artist. His academic training at Bradford School of Art, which emphasized drawing, painting, and the study of anatomy and perspective, provided the foundation for his career.

The works in this section demonstrate the evolution of Hockney’s practice, built upon his natural aptitude as a draftsman. At the Royal College of Art in London, where he enrolled in 1959, Hockney threw himself into life classes. In 1960, a Picasso retrospective at the Tate marked the beginning of a fascination with the modern master, whose eclecticism was a formative influence on the young artist.

Although homosexuality remained illegal in England until 1967, Hockney took up overtly gay themes in his work at the Royal College before almost anyone else. In A Rake’s Progress, a personal narrative of his first trip to the United States in the summer of 1961—influenced by the eighteenth-century print series by William Hogarth—Hockney’s sense of his own identity began to emerge.

Artwork: © David Hockney

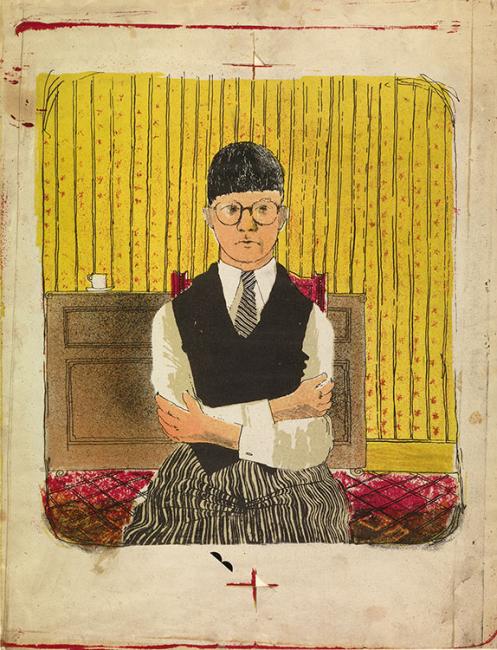

Self-Portrait, 1954

The self-portraits Hockney made in his teenage years, such as the present one and the pencil drawings nearby, convey a youthful confidence as well as the beginnings of an intense self-scrutiny. The full-frontal pose and attention to detail in clothes and styling reflect Hockney’s burgeoning sense of his own identity. This collage also offers a foretaste of Hockney’s later works, notably his vibrant palette and experimentation with different media.

The self-portraits Hockney made in his teenage years, such as the present one and the pencil drawings nearby, convey a youthful confidence as well as the beginnings of an intense self-scrutiny. The full-frontal pose and attention to detail in clothes and styling reflect Hockney’s burgeoning sense of his own identity. This collage also offers a foretaste of Hockney’s later works, notably his vibrant palette and experimentation with different media.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 1954

Collage on newsprint

Bradford Museums and Art Galleries, Cartwright Hall

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

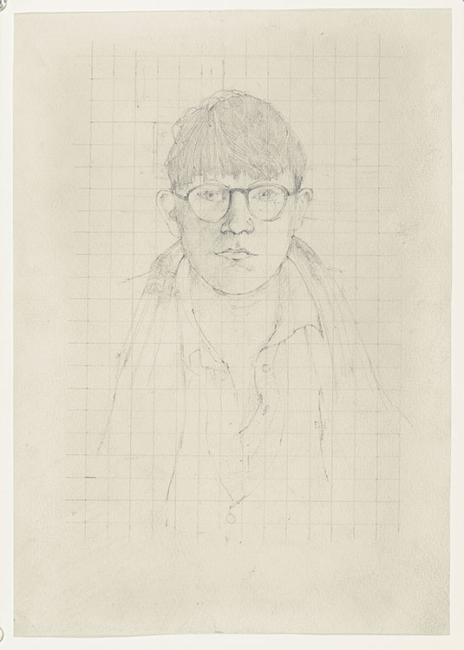

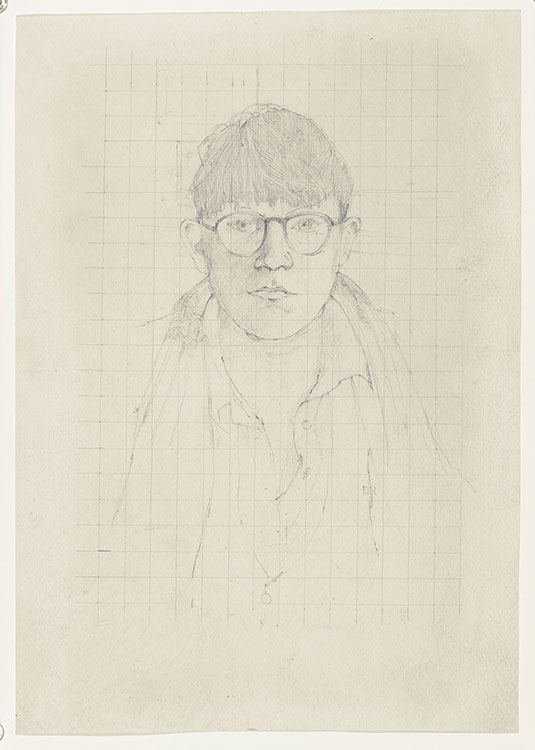

Self Portrait Study, 1954

David Hockney

Self Portrait Study, 1954

Pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

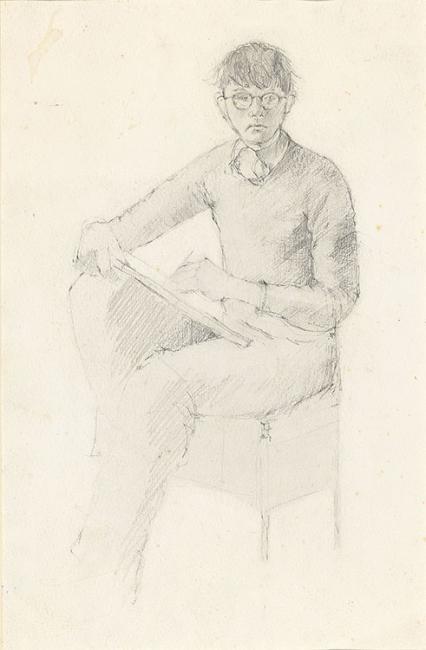

Self Portrait, 1954

David Hockney

Self Portrait, 1954

Lithograph

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

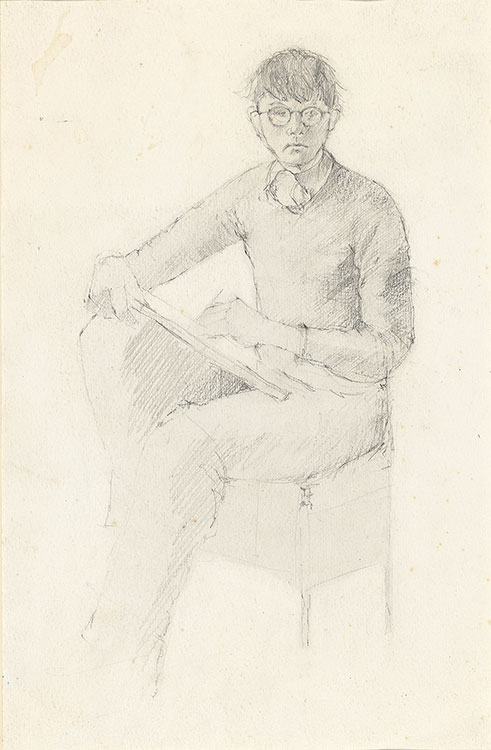

Self Portrait, 1956

David Hockney

Self Portrait, 1956

Pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

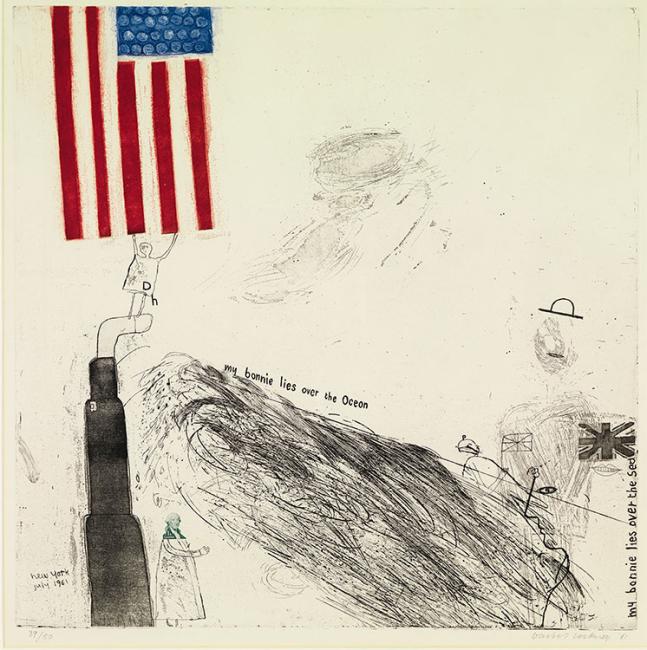

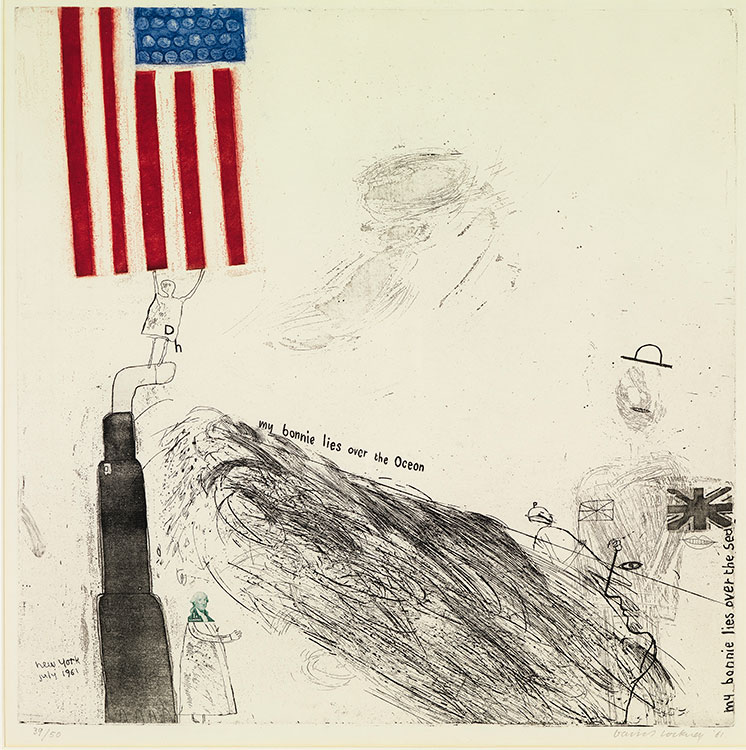

My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean

David Hockney

My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean, 1961

Etching and aquatint with collage

Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Myself and My Heroes

While at the Royal College of Art in London, Hockney turned to etching for pragmatic reasons. Students were responsible for purchasing their own supplies and Hockney had quickly run out of money thanks to his enthusiasm for painting, so he took advantage of the college’s free printmaking materials. His first etching, Myself and My Heroes, embraces several of his passions at the time: the homoerotic poetry of Walt Whitman and the pacifism and vegetarianism of Mahatma Gandhi.

David Hockney

Myself and My Heroes, 1961

Etching in black with aquatint

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

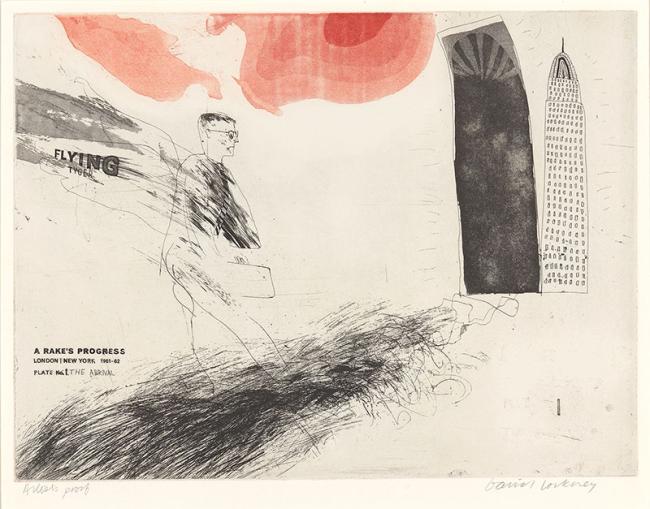

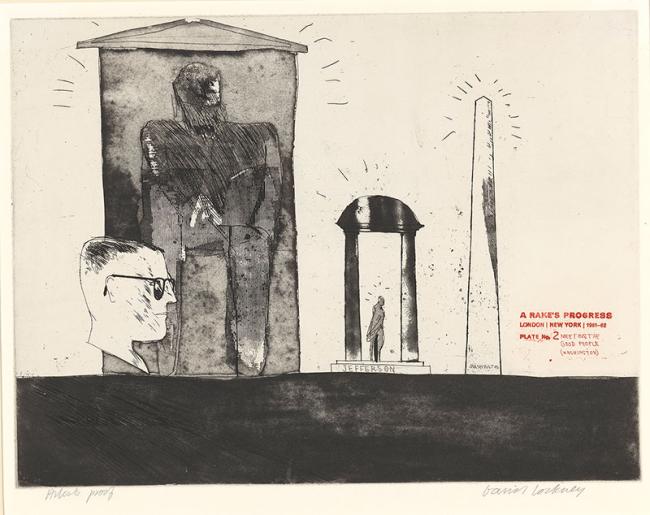

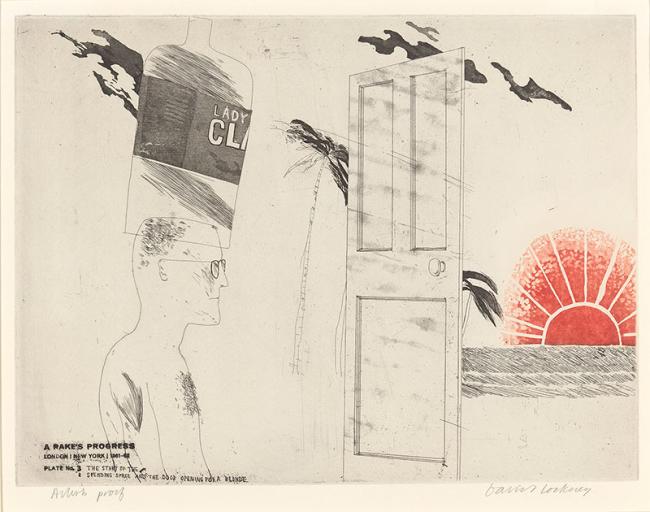

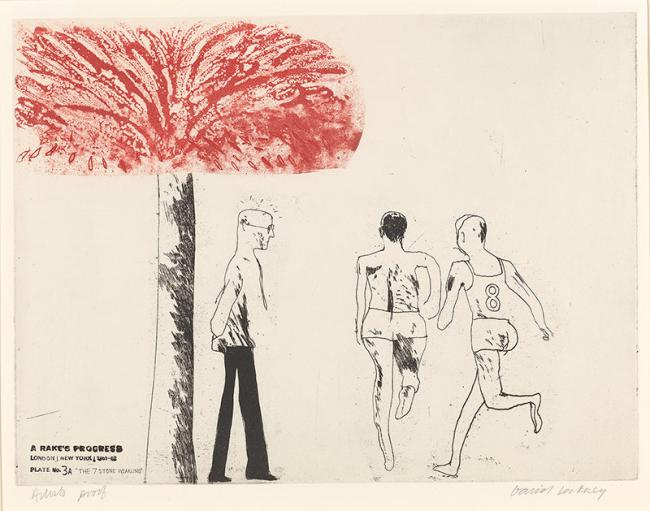

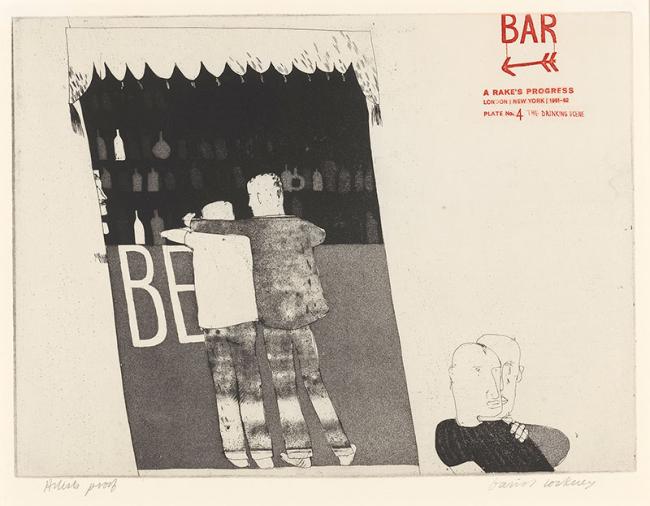

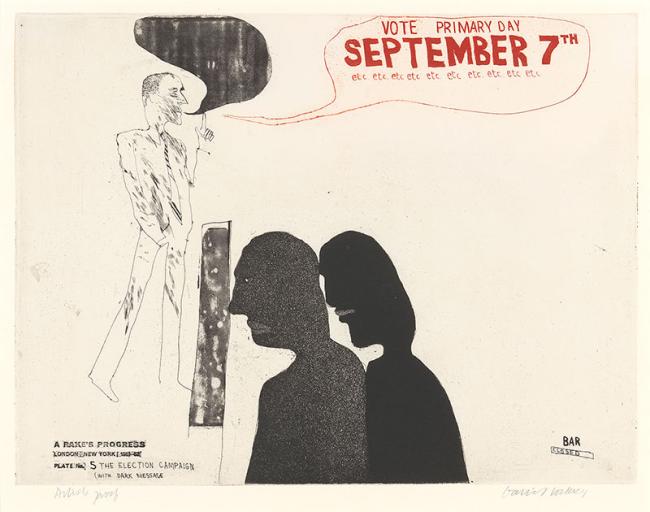

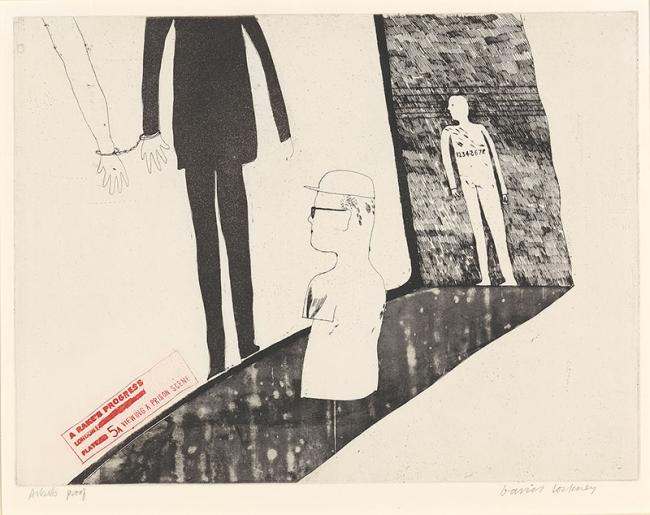

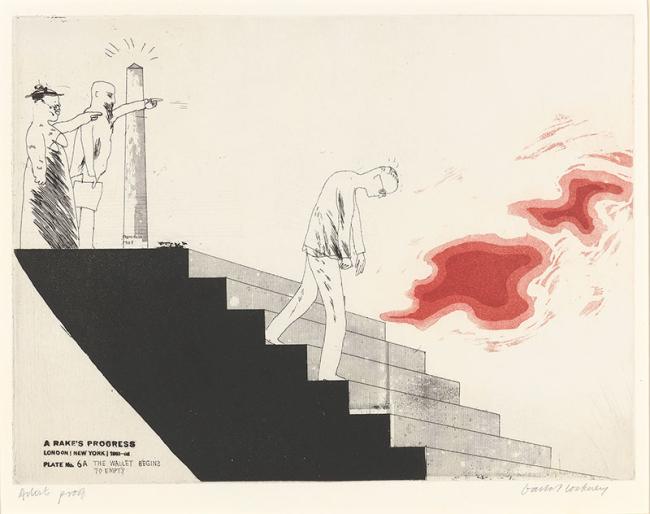

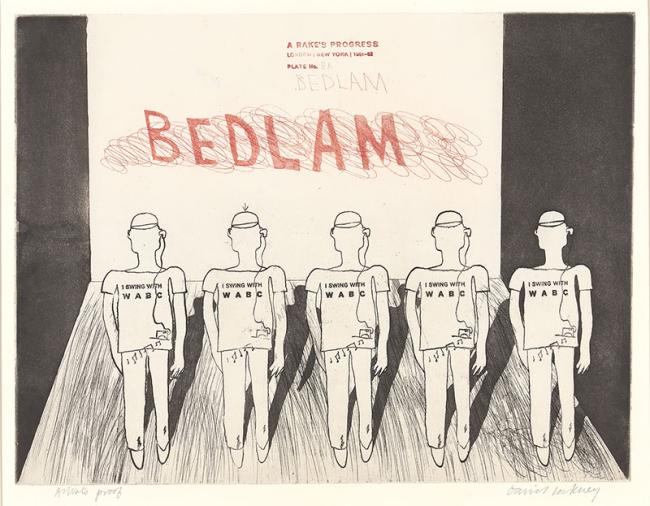

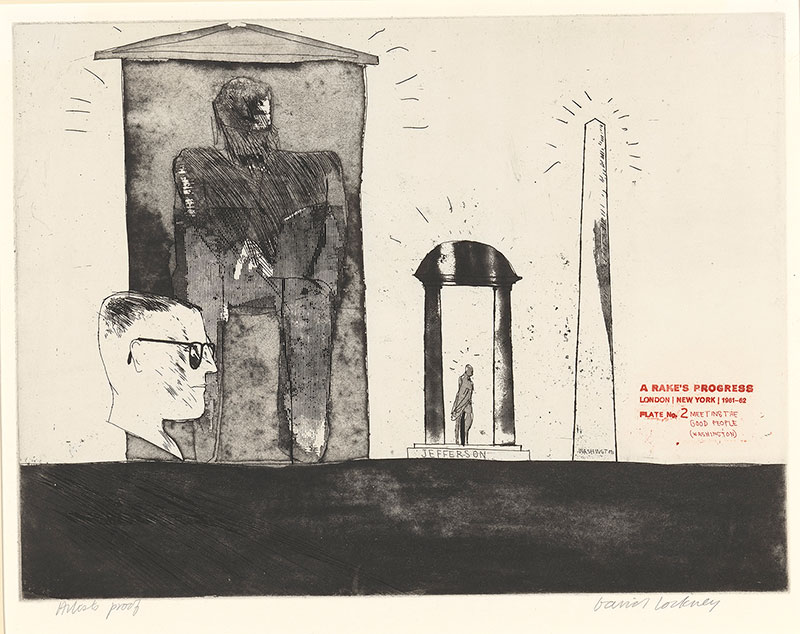

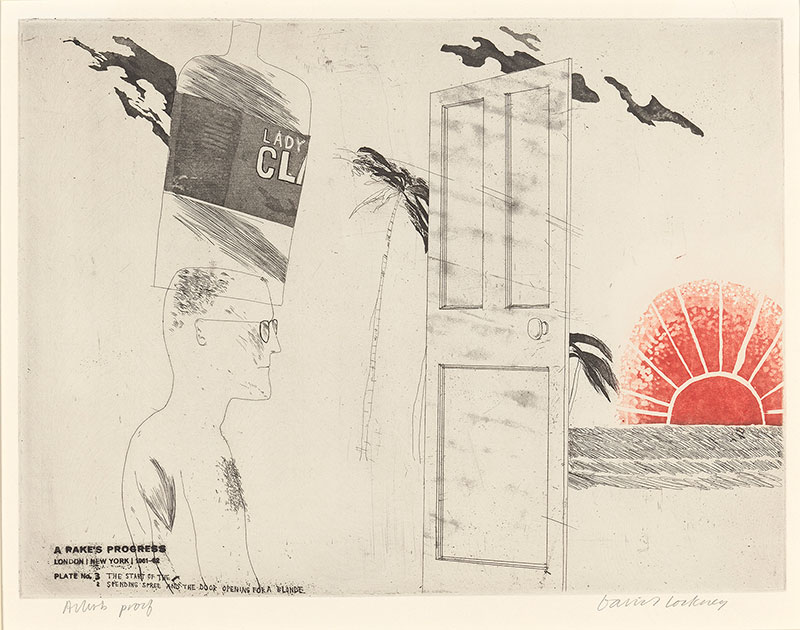

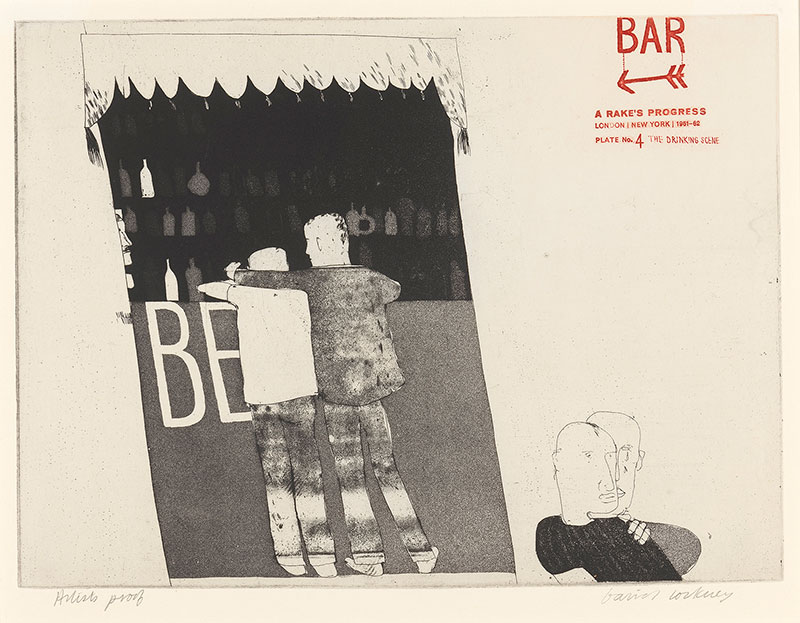

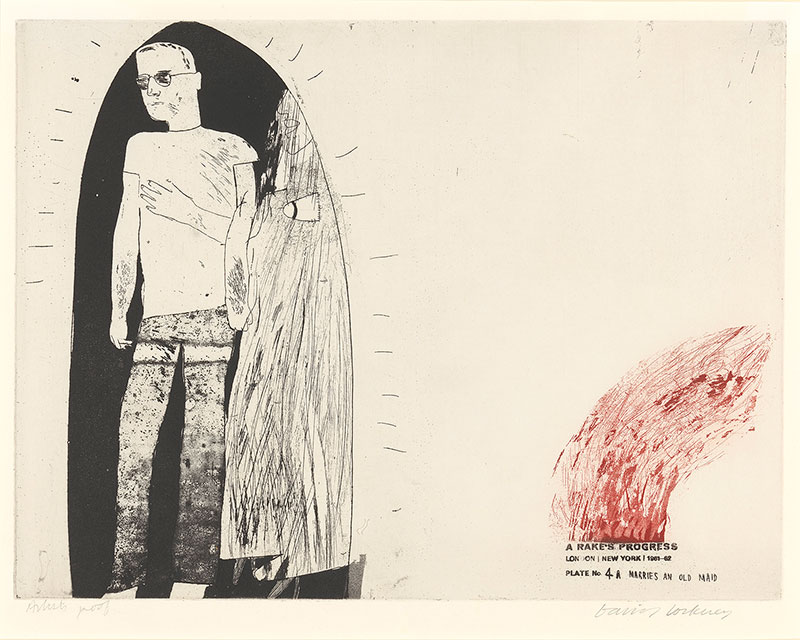

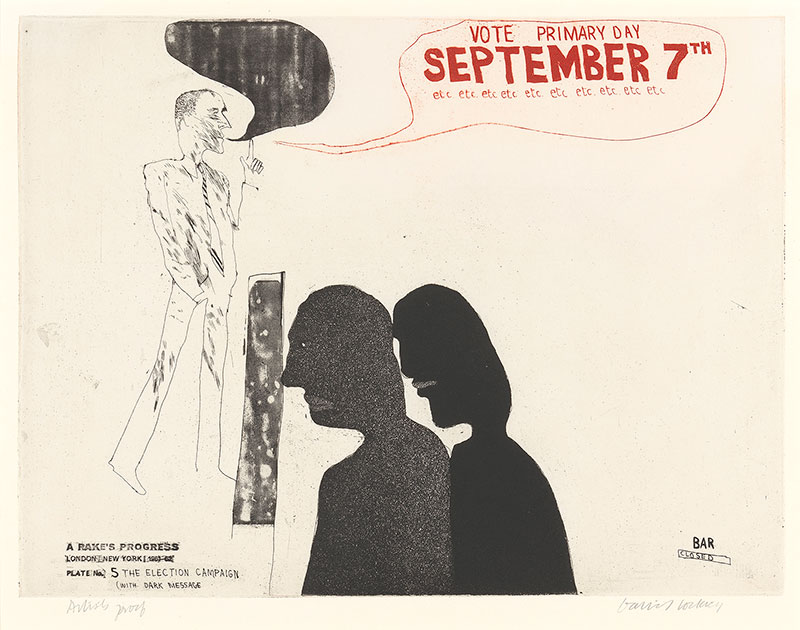

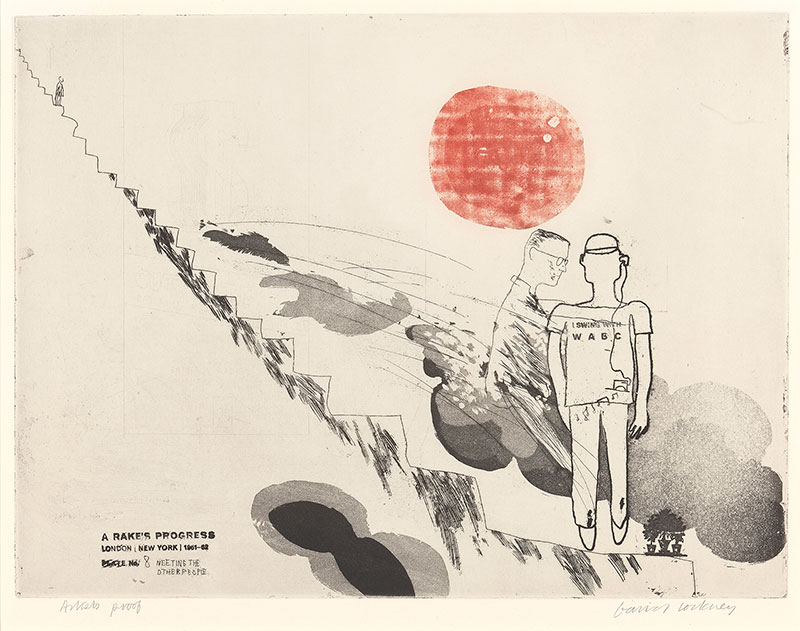

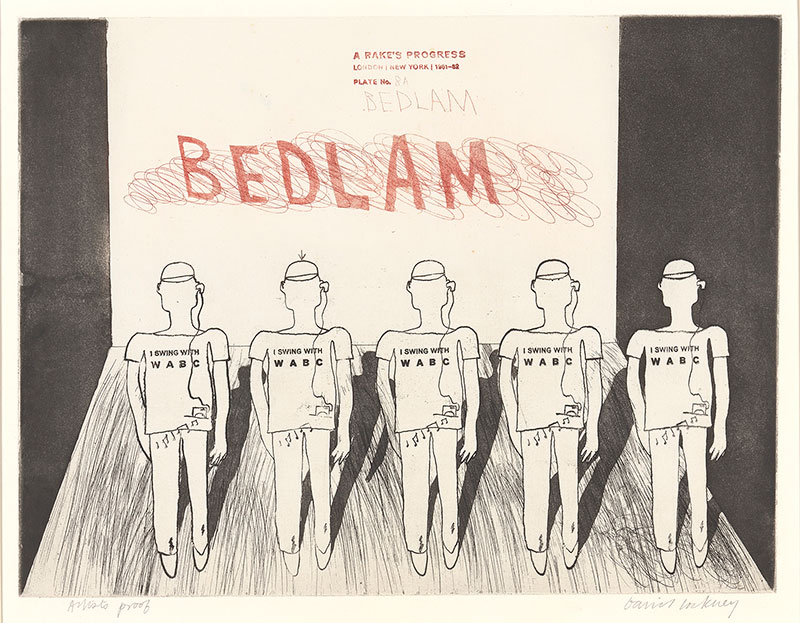

A Rake’s Progress, 1961–63

Hockney’s first visit to the United States, in the summer of 1961, provided the narrative for this semiautobiographical series. Inspired by William Hogarth’s 1735 engraving series of the same title, Hockney transformed the tale of an aristocrat who squanders his wealth into his own personal story of a young gay man’s journey and emerging identity in 1960s New York City. Although Hockney claimed that “It is not really me. It’s just that I use myself as a model because I’m always around,” the etchings were partly inspired by real events. Plate 1a records his meeting with William S. Lieberman, then curator of drawings and prints at the Museum of Modern Art, who bought two prints from him, including Myself and My Heroes. The name “Lady Clairol” on plate 3 refers to the brand of hair dye Hockney used to bleach his hair for the first time. A range of artistic influences can be traced, from the figures of William Blake to the art brut of Jean Dubuffet.

The Arrival

David Hockney

The Arrival from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Receiving the Inheritance

David Hockney

Receiving the Inheritance from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Meeting the Good People (Washington)

David Hockney

Meeting the Good People (Washington) from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

The Gospel Singing (Good People) Madison Square Garden

David Hockney

The Gospel Singing (Good People) Madison Square Garden, 1961–1963

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

The Start of the Spending Spree and the Door Opening for a Blonde

David Hockney

The Start of the Spending Spree and the Door Opening for a Blonde from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963,

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

The Seven Stone Weakling

David Hockney

The Seven Stone Weakling from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

The Drinking Scene

David Hockney

The Drinking Scene from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Marries an Old Maid

David Hockney

Marries an Old Maid from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

The Election Campaign (with Dark Message)

David Hockney

The Election Campaign (with Dark Message) from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Viewing a Prison Scene

David Hockney

Viewing a Prison Scene from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Death in Harlem

David Hockney

Death in Harlem from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

The Wallet Begins to Empty

David Hockney

The Wallet Begins to Empty from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Disintigration

David Hockney

Disintigration from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Cast Aside

David Hockney

Cast Aside from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Meeting the Other People

David Hockney

Meeting the Other People from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Bedlam

David Hockney

Bedlam from A Rake's Progress, 1961–1963

Etching, aquatint

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

The Diploma

David Hockney

The Diploma, 1962

Etching with aquatint

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

The Student: Homage to Picasso

David Hockney

The Student: Homage to Picasso, 1973

Etching, soft ground etching, lift ground etching

National Portrait Gallery, London. Purchased, 1979

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

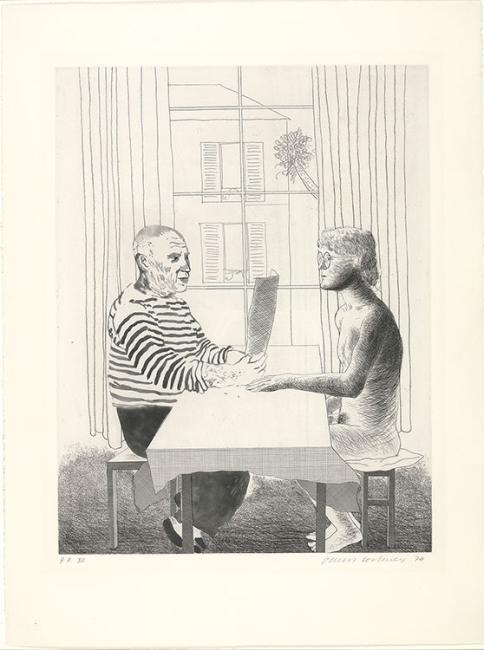

Artist and Mode

Following Picasso’s death in April 1973, Hockney made two etchings in the spirit of Picasso’s renowned Vollard Suite (1930−37). In the present one, Hockney depicts an imaginary meeting with the modern master, casting himself as the nude model and using different etching techniques to distinguish the two: for Picasso, the looser “sugar-lift” method—which involves brushing the figure directly on the plate with a sugar-based fluid—and a more densely hatched line for himself. Hockney had been taught the sugar-lift technique that year in Paris by Aldo Crommelynck, the master printer of Picasso’s later etchings.

David Hockney

Artist and Model, 1973–1974

Etching

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

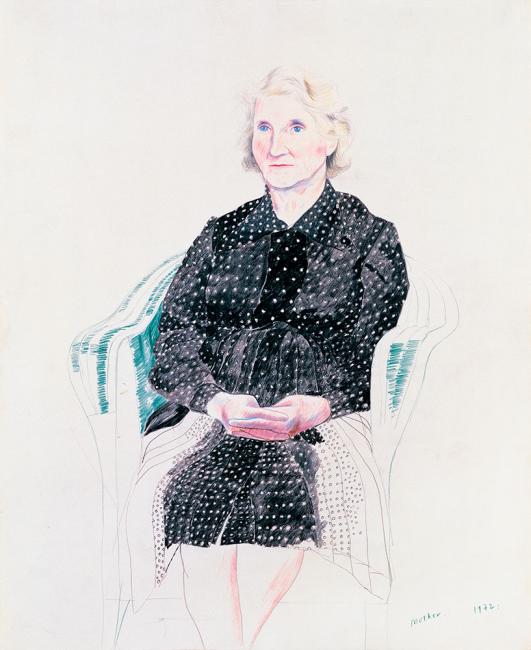

The Artist’s Mother

The large number of portraits Hockney made of his mother attests to the close bond between them. A devout Methodist and strict vegetarian, Laura Hockney (1900−1999) raised her four children with great generosity of spirit. Supportive of her son David’s desire to be an artist, she remained a loyal and patient model who would always sit still for him.

Although Hockney is critical of photography— “A photograph cannot really have layers of time in it the way a painting can, which is why drawn and painted portraits are much more interesting,” he once said—the large portrait that dominates this section was made from photographs. In 1982, Hockney began creating collages with Polaroid prints, which he worked into grids. He eventually went on to create more complex images with irregular edges using 35 mm photographs, such as this portrait of his mother. The influence of Picasso and Cubism is evident in these works, in which he captures simultaneous viewpoints and a narrative that reflects the passage of time. Hockney compared the photocollage pro- cess to a kind of drawing: “I felt these pictures were linear, and that in piecing them together, picture by picture, I was really drawing line, linking them.”

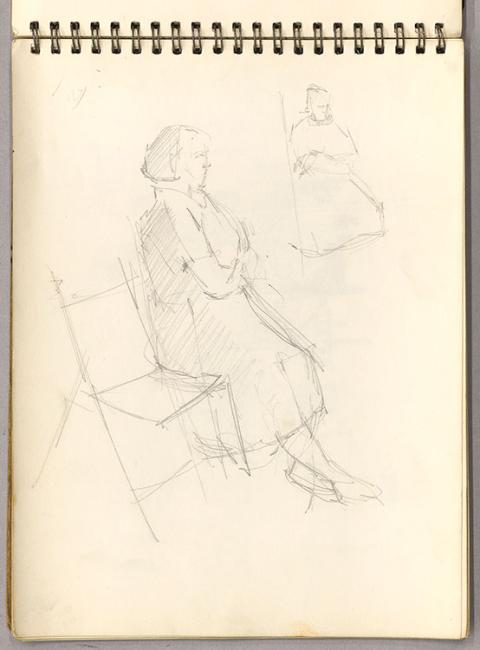

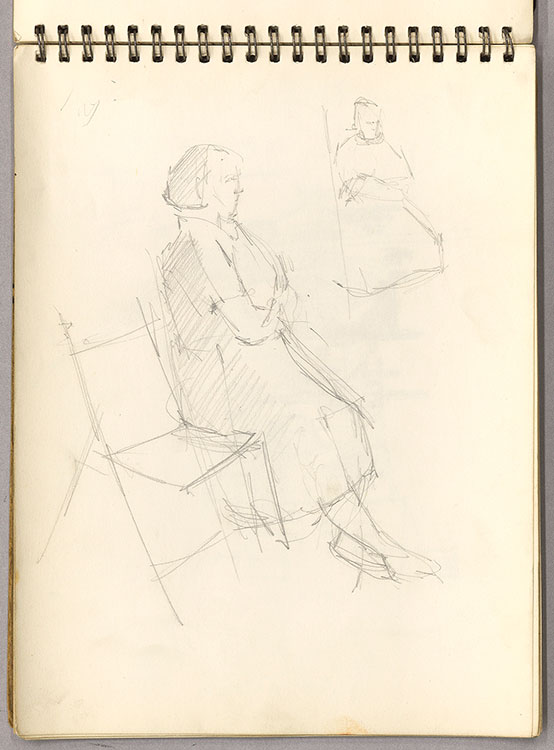

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook)

David Hockney

David Hockney

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), 1953, Page 4

Pencil, ink and wash

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

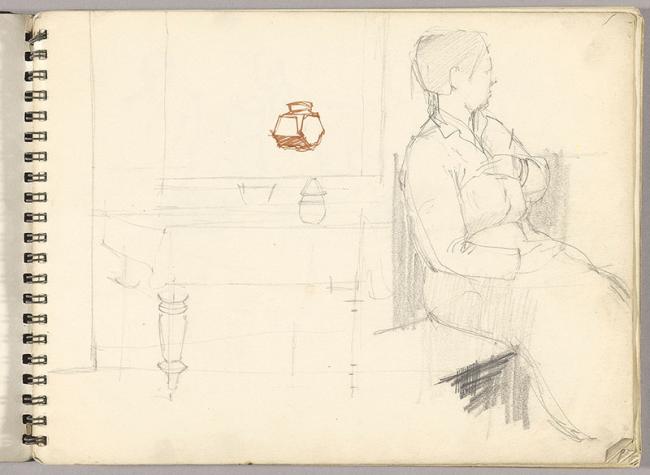

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook)

David Hockney

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), 1953, Page 48

Pencil, ink and wash

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), Page 3

David Hockney

David Hockney

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), 1953, Page 36

Pencil, ink and washon

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), Page 52

David Hockney

David Hockney

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), 1953, Page 52

Pencil, ink and wash

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), Page 56

David Hockney

David Hockney

Bradford School of Art 1 (Sketchbook), 1953, Page 56

Pencil, ink and wash

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Mother, Paris

David Hockney

Mother, Paris, 1972

Colored pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

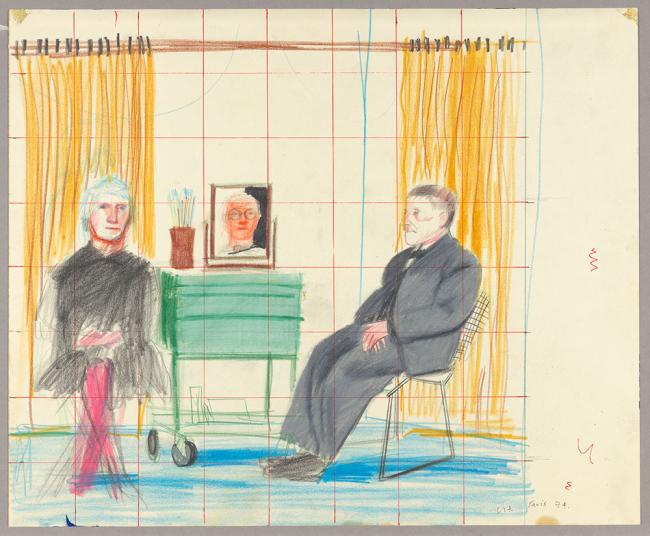

Study for "My Parents and Myself"

While Hockney was living in Paris intermittently from 1973 to 1975, he was visited by his parents and began making preparatory drawings for a painting of them. His father worked as a clerk but was also an amateur artist and antismoking campaigner, well known for his strong political views. His mother was a quiet but strong matriarchal figure. The artist inserted himself into the picture through his reflection in the mirror on the cart.

David Hockney

Study for “My Parents and Myself,” 1974

Colored pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Mother, Bradford. 19 Feb 1979

Hockney made this drawing on 19 February 1979, the day of his father’s funeral. When he signed and dated it later, however, he mistakenly inscribed the year 1978. Relying on a minimal line, the artist conveys the sadness in his mother’s face as she looks directly at her son. The use of sepia ink applied with a reed pen—a possible reference to Van Gogh— gives his mother a softer, more vulnerable air than in the earlier pen-and-ink portraits. Making a drawing was less intrusive than taking a photograph would have been. Drawing had become Hockney’s way of communicating with his mother.

David Hockney

Mother, Bradford. 19 Feb 1979, 1979

Sepia ink on paper The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

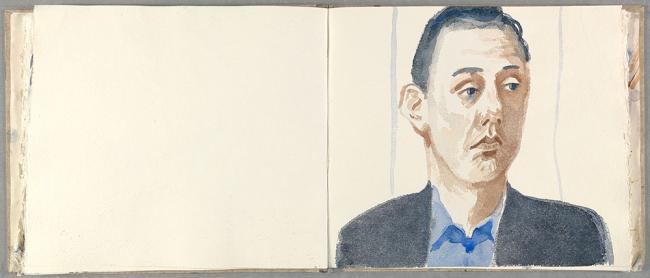

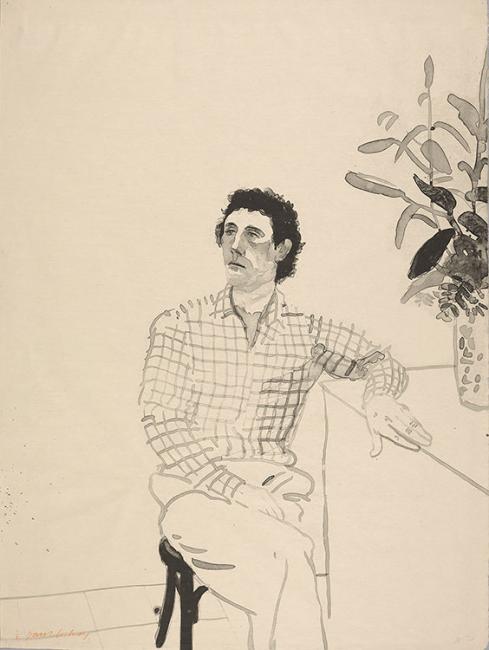

Gregory

Hockney met Gregory Evans in London through the Los Angeles art dealer Nicholas Wilder. They began an intimate relationship in Paris in 1974, when both lived on the left bank of the Seine. Over time, Gregory’s role evolved from lover and studio assistant to curator and trusted adviser, but he has remained a close friend and consistent model for nearly fifty years.

Gregory’s portraits chart the trajectory of Hockney’s practice, from quick sketches in pen and ink to more detailed renderings in pencil. In the mid-1960s, Hockney started using a technical pen called a Rapidograph, which maintains a constant line width. Over the next decade, he finessed the technique in a series of figure studies characterized by an economical, unbroken line. Working quickly, with intense concentration, he was able to create the impression of a moment frozen in time. In the pencil drawings, by contrast, he varied the thickness and type of line to convey subtleties of form, texture, and tone.

Gregory, 1978

David Hockney

Gregory, 1978

Colored pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

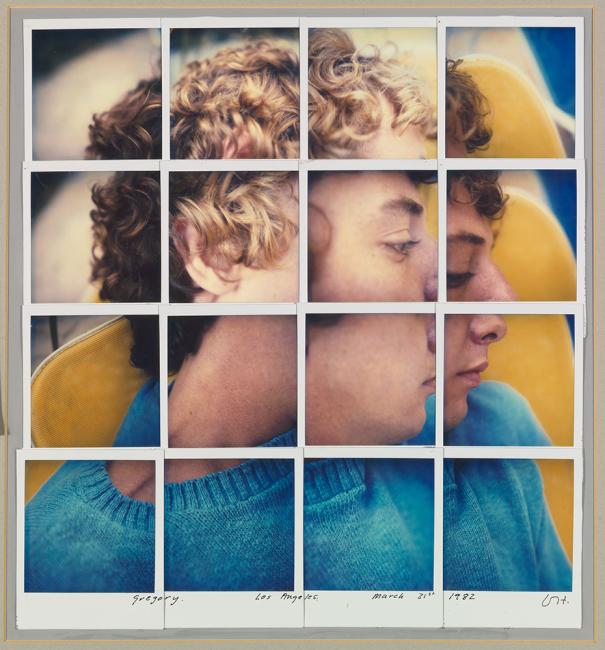

Gregory, Los Angeles, March 31st 1982

“The moment you make a collage of photographs,” Hockney said, “it becomes something like a drawing.” In February 1982, he began assembling Polaroids into grids to form what he called “joiners,” composite images in which each photograph shows a detail of the subject. The process of selection and juxtaposition produces a more complex, multilayered portrayal than a single photograph, which the artist found “too devoid of life.” Hockney made portraits of his favorite models using this technique (see the composite Polaroids of Celia and Maurice elsewhere in this exhibition), but after a few months he abandoned the rigidity of the grid in favor of freer types of photocollages.

David Hockney

Gregory, Los Angeles, March 31st 1982, 1982

Composite polaroid

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

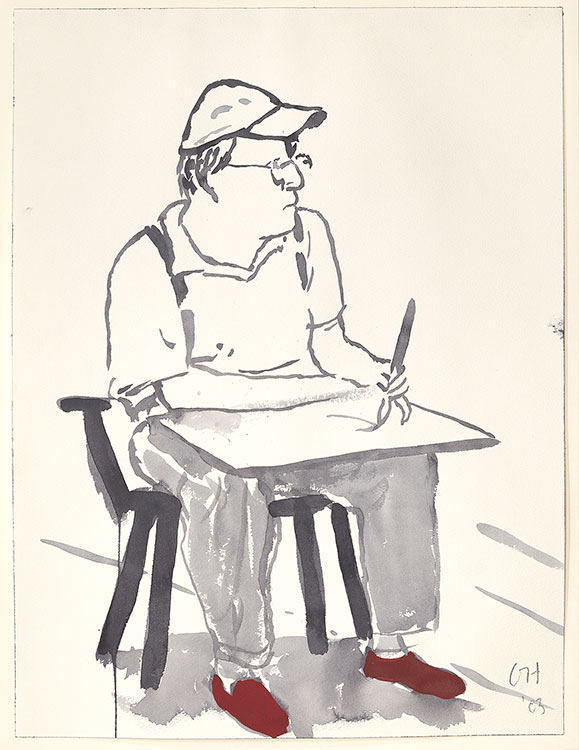

España (Spain) January 2004

David Hockney

España (Spain) January 2004, 2004

Watercolor on sketchbook page

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

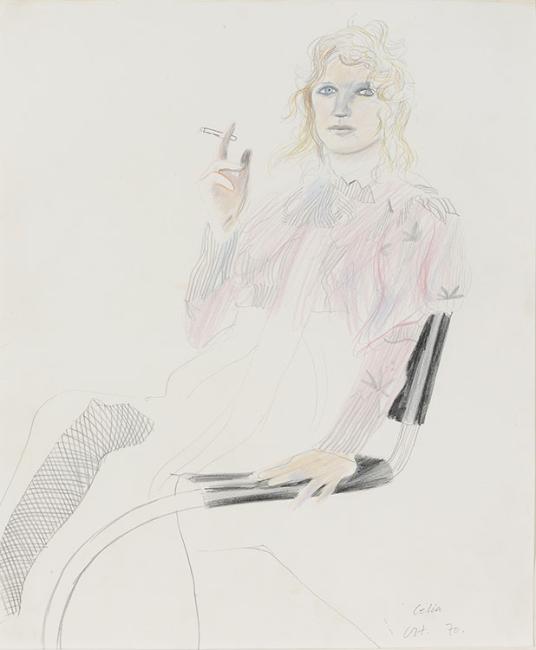

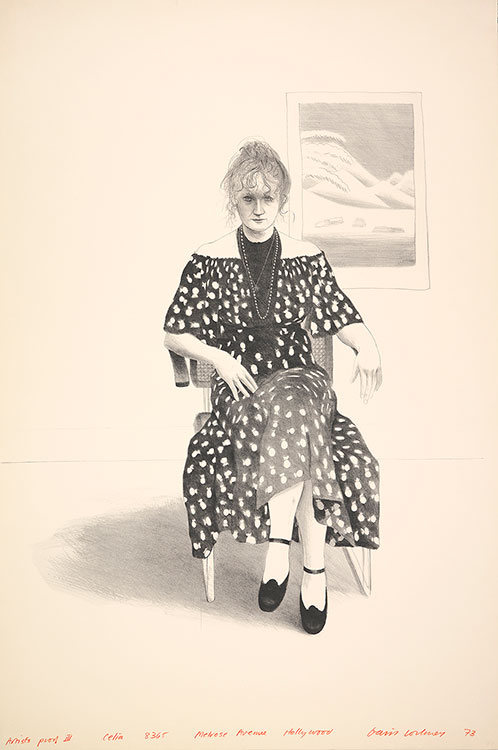

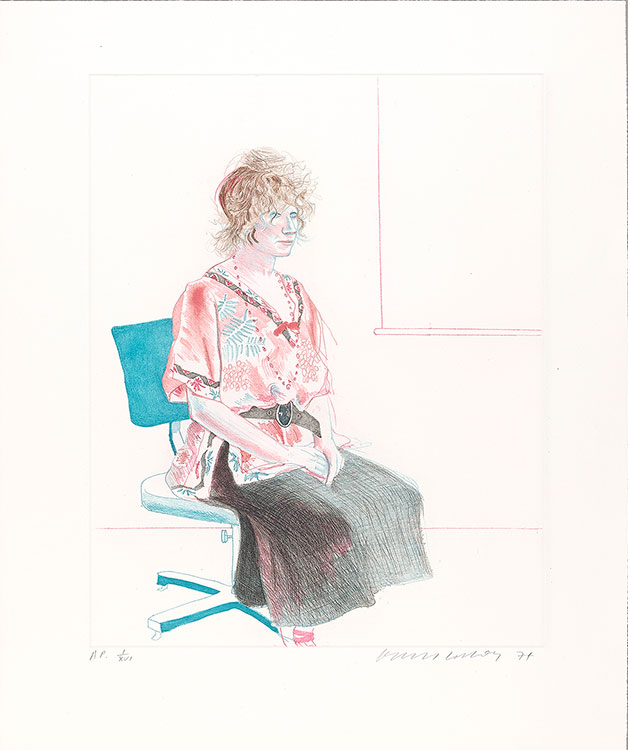

Celia

The British textile and fashion designer Celia Birtwell has been a close friend and confidante of Hockney’s since the 1960s. Sharing northern roots and a similar sense of humor, the two found they had much in common from their first meeting and together they were at the heart of bohemian London. Hockney has always been fascinated by the changing nature of Celia’s face and she remains, to this day, one of his favorite models.

Although Celia is often described as Hockney’s “muse,” their relationship is more than that. They have always admired each other’s work and her sittings for him have been collaborations, as well as an opportunity to enjoy one another’s company. In his portraits of Celia, Hockney has always paid close attention to her bold and romantic fabric designs, some of which are inspired by his work

Artwork: © David Hockney

Celia, 1970

David Hockney

Celia, 1970

Pencil and colored crayon on paper

Private collection

© David Hockney, © Julie Green

Photography by Hugh Kelly

Celia, Carennac, August 1971

David Hockney

Celia, Carennac, August 1971, 1971

Colored pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Celia, Nov 10 1972

David Hockney

Celia, Nov 10 1972, 1972

Crayon on paper

Private collection

© David Hockney

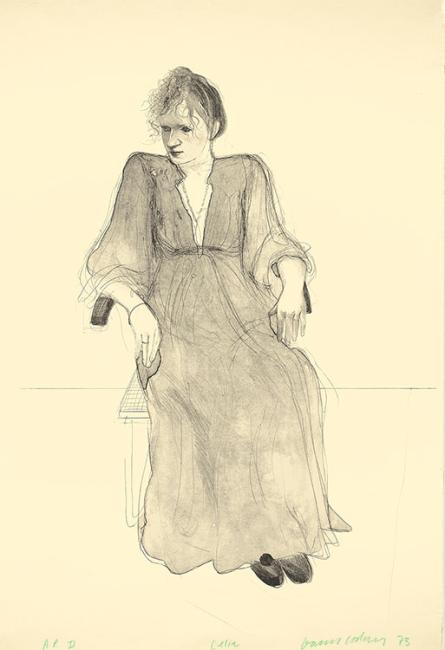

Celia, 1973

David Hockney

Celia, 1973

Lithograph

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney / Gemini G.E.L.

Photography by Richard Schmidt

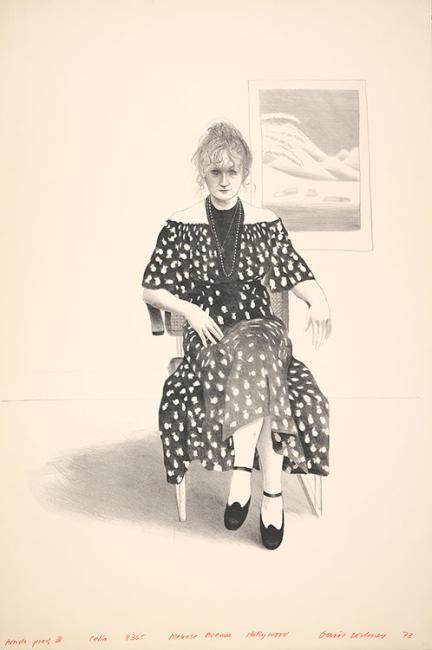

Celia, 8365 Melrose Avenue, Hollywood

David Hockney

Celia, 8365 Melrose Avenue, Hollywood, 1973

Lithograph

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney / Gemini G.E.L.

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Celia Seated in an Office Chair (Color

David Hockney

Celia Seated in an Office Chair (Color), 1974

Etching and soft-ground etching with aquatint

Collection of Gregory Evans

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

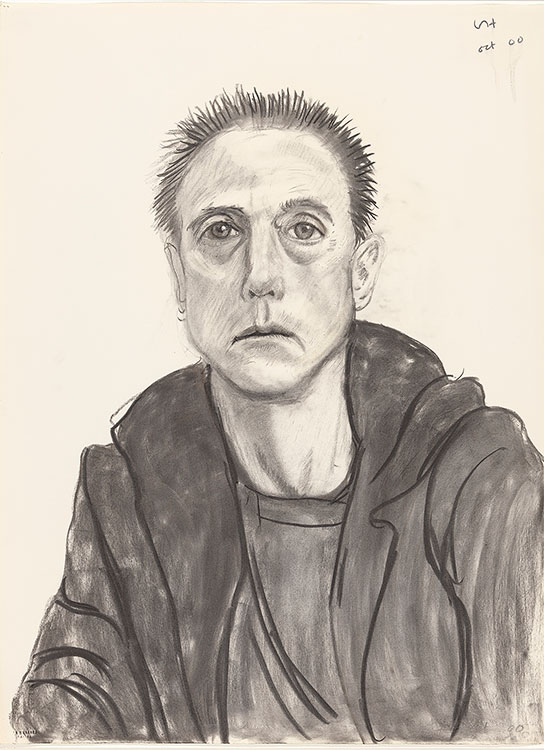

Maurice

The lifelong friendship between Hockney and master printer Maurice Payne began in London in the mid-1960s, when they worked together on the etching suite Illustrations for Fourteen Poems from C. P. Cavafy (1967). They continued to collaborate on significant print projects until the late 1970s.

In 1998, after a hiatus of twenty years, they again worked together when Maurice set up a print studio in Los Angeles. To encourage Hockney, he would take pre-prepared etching plates up to the artist’s house in the Hollywood Hills, then bring them back down to the printing press he had set up in Hockney’s studio in West Hollywood. Working from life, Hockney drew still lifes and portraits of friends. These intimate drawings created in the domestic setting of his home contrast with the monumental landscapes of the American West he was painting in his studio at the time.

Artwork: © David Hockney

Maurice with Flowers

David Hockney

Maurice with Flowers, 1976

Lithograph

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

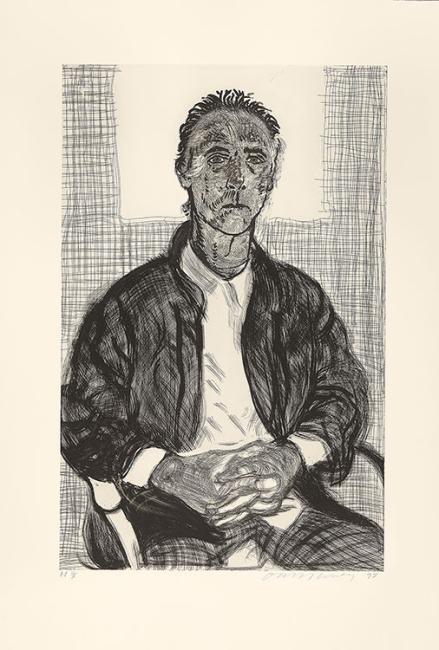

Maurice, 1998

In their print projects, Maurice Payne encouraged Hockney to work in innovative ways. Here, the artist’s characteristic line drawing, so well suited to the etching technique, is combined with the use of unconventional tools such as a wire brush to create texture and volume. Print production was a process of discovery for both Payne and Hockney. "We learned as we went along," the master printer later revealed. The expressive mark-making, as well as the sitter’s full-frontal pose, suggests the influence of Van Gogh’s portraits.

David Hockney

Maurice, 1998

Etching

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

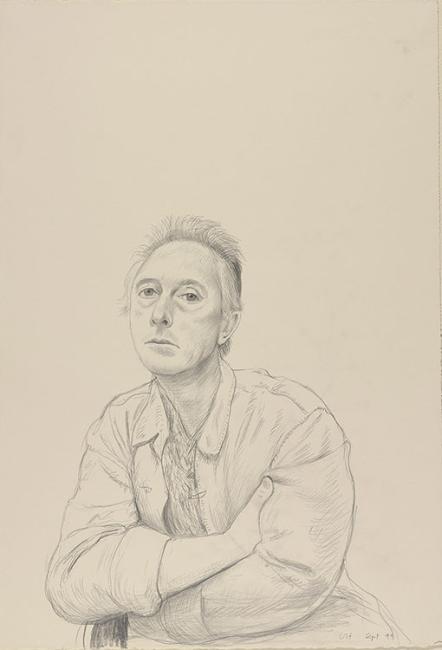

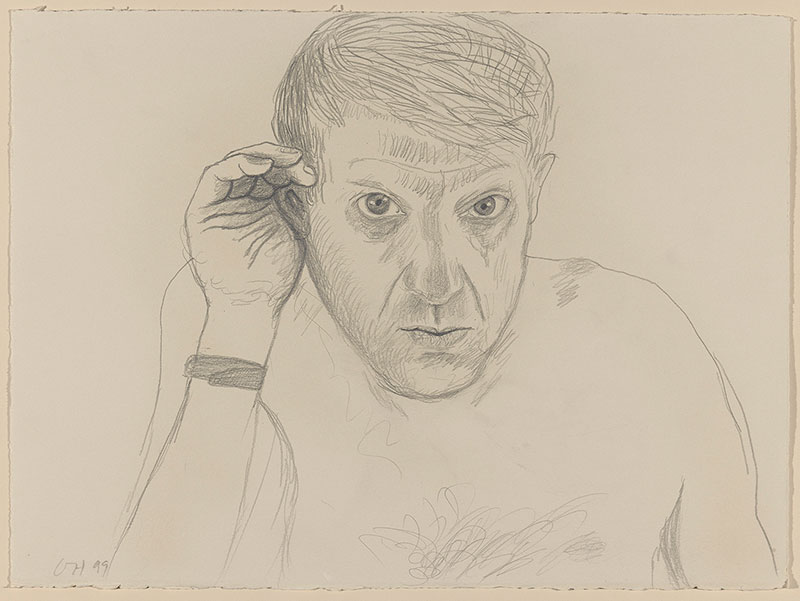

Maurice Payne. Los Angeles

In his book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, Hockney describes the process of using a camera lucida:

Basically, it is a prism on a stick that creates the illusion of an image of whatever is in front of it on a piece of paper below. . . . When you look through the prism from a single point you can see the person or objects in front and the paper below at the same time. . . . You must use it quickly, for once the eye has moved the image is really lost. A skilled artist could make quick notations, marking the key points of the subject’s features. . . . After these notations have been made, the hard work begins of observing from life and translating the marks into a more complete form.

David Hockney

Maurice Payne. Los Angeles. 11th September 1999, 1999

Pencil on paper, using a camera lucida

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

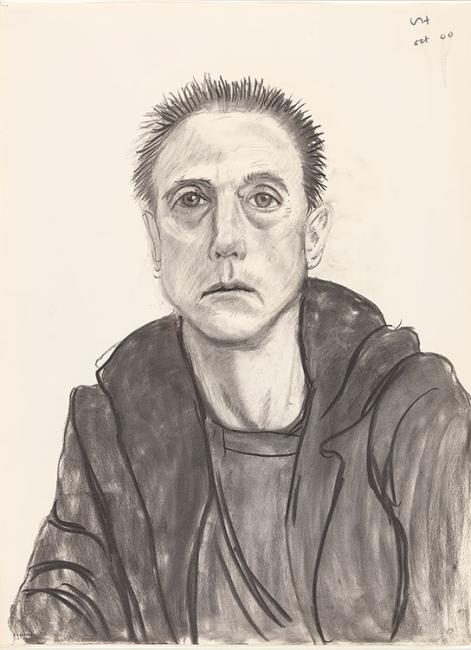

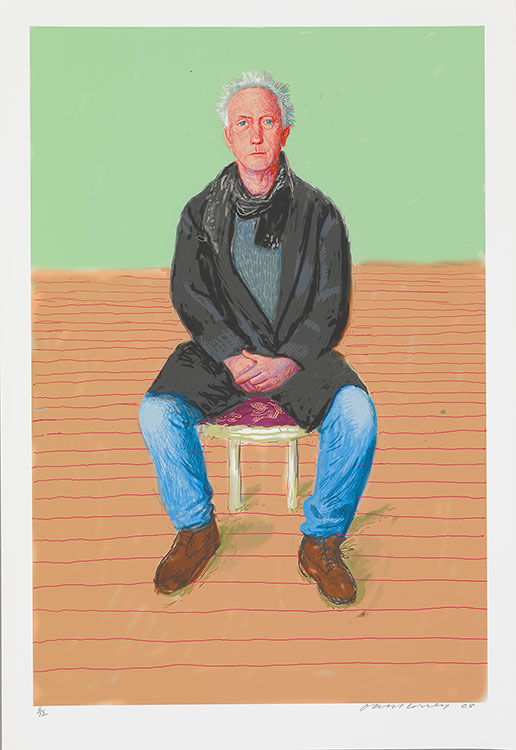

Maurice Payne, October 9, 2000

David Hockney

Maurice Payne, October 9, 2000, 2000

Charcoal on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

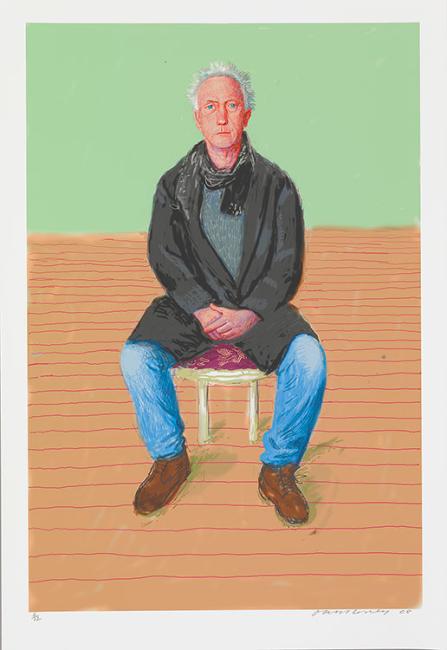

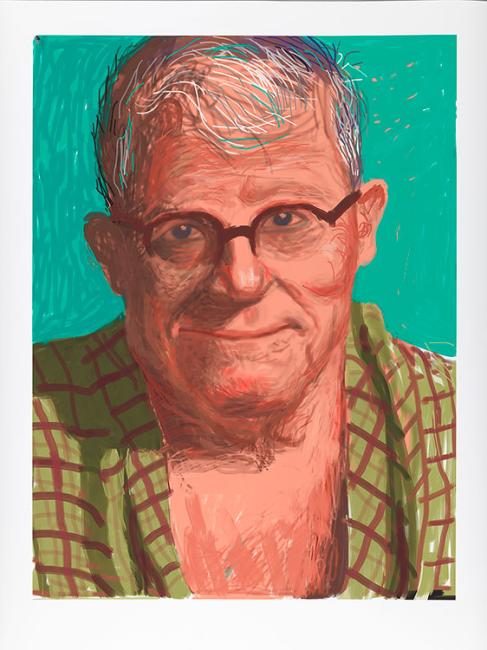

Maurice Payne, 2008

New digital technology sparked creative experiments in Hockney’s work. In 2008, he began making computer drawings using Photoshop, as in this portrait of Maurice, one of a series of portraits of family, friends, and colleagues drawn in his large studio in Bridlington, Yorkshire. By then, Hockney felt that computer software had advanced enough to keep up with the artist’s hand. He particularly admired the speed with which he could draw with color “directly in a printing machine,” as he described it, unlike the slow process of swapping brushes with oil or watercolor.

David Hockney

Maurice Payne, 2008

Inkjet-printed computer drawing on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

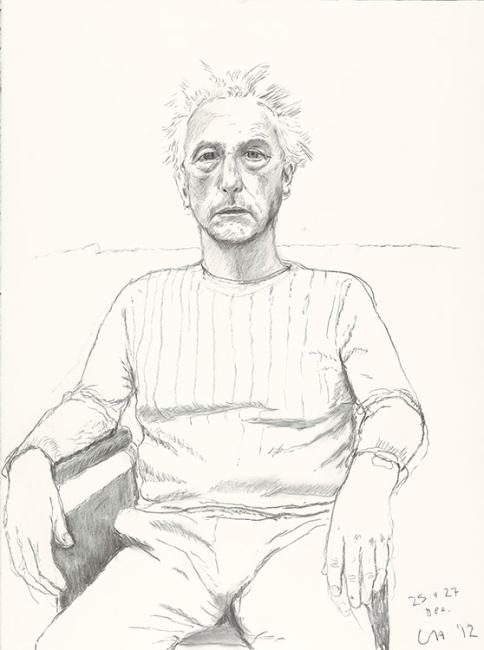

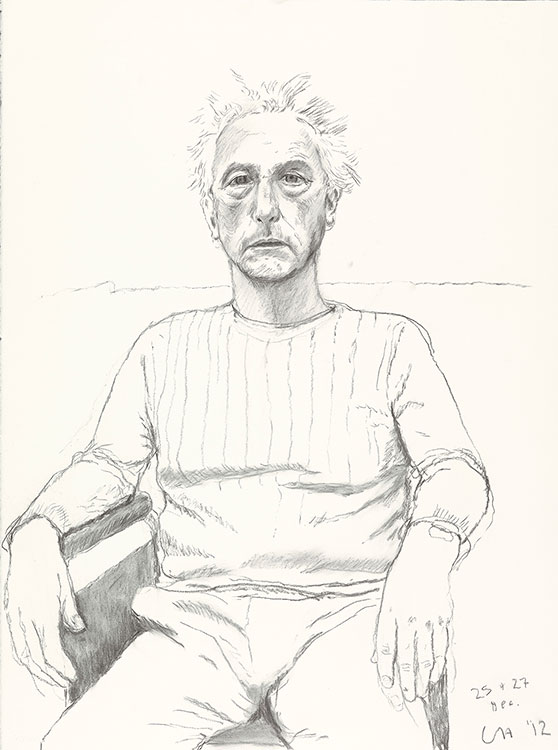

Maurice Payne, 25 and 27 December 2012

David Hockney

Maurice Payne, 25 and 27 December 2012, 2012

Charcoal on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Maurice Payne, 16 April 201

David Hockney

Maurice Payne, 16 April 2013, 2013

Charcoal on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

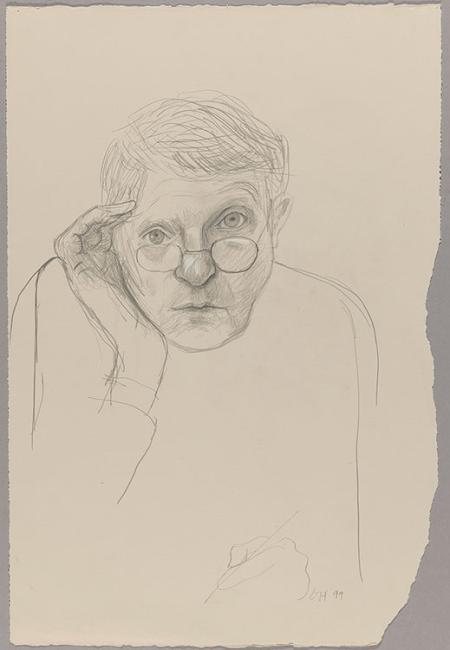

Portraits for a New Millennium

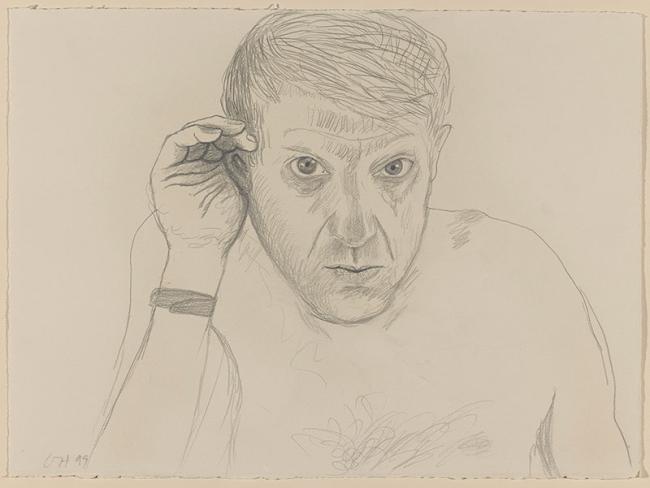

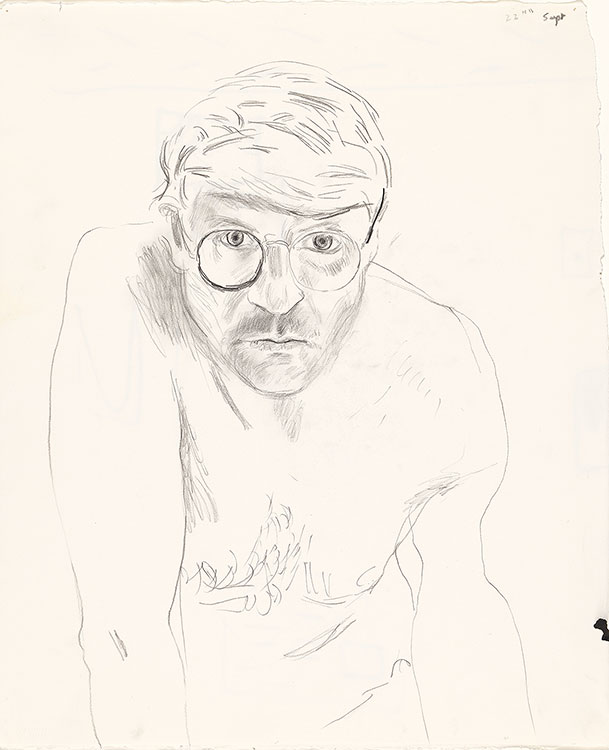

In the 1980s, while he experimented with neo-Cubist distortions in his paintings, Hockney continued to make traditional drawings as a means of looking inward. In the autumn of 1983, he produced a series of contemplative self-portraits in which he observed himself, as a middle-aged man, with honesty and vulnerability. “I just thought I’d look at myself. As I go deafer, I tend to retreat into myself, as deaf people do,” he explained. In another self-portrait series, executed in 1999, he adopted a more playful attitude in a range of facial expressions.

A few years later, Hockney turned to watercolor, a medium he had not explored since the 1960s. This new way of working freed up his approach, allowing him to draw quickly and directly on paper. He described these watercolors as “portraits for the new millennium,” convinced that, despite his experimentation with photography and other technologies, the human eye and hand were still the best tools for capturing the individuality of his sitters.

Artwork: © David Hockney

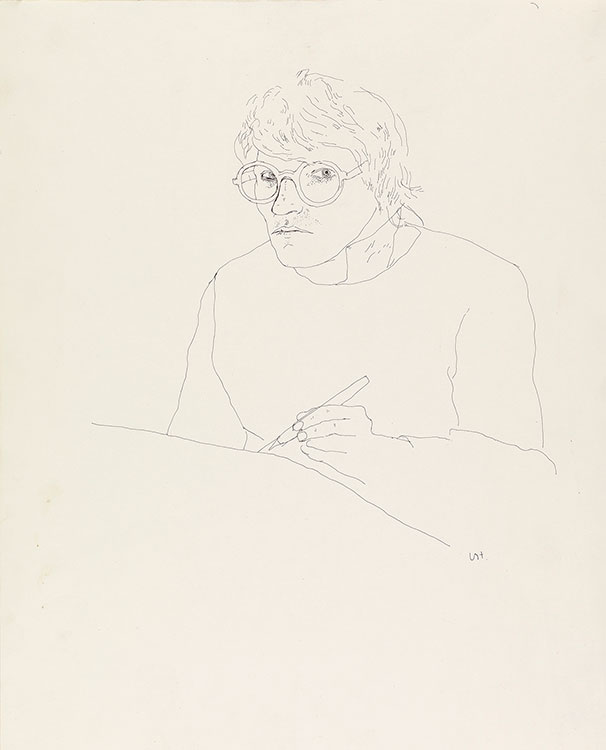

Self Portrait with Pen

David Hockney

Self Portrait with Pen, 1969

Ink on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self Portrait, 1980

David Hockney

Self Portrait

1980

Lithograph

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney / Gemini G.E.L.

Photography by Richard Schmidt

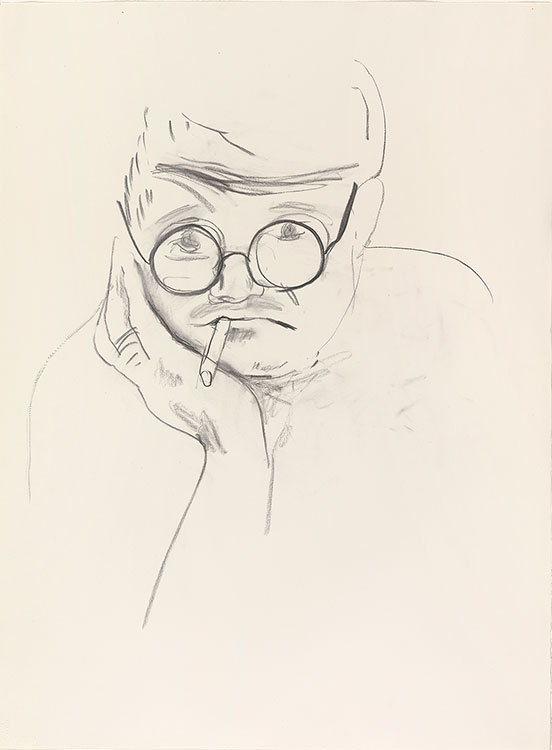

Self Portrait with Cigarette, 1983

David Hockney

Self Portrait with Cigarette, 1983

Charcoal on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

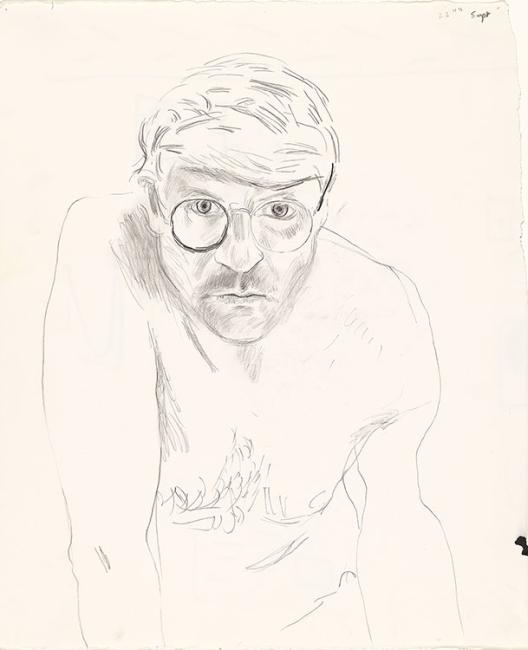

Self-Portrait, 22nd Sept. 1983

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 22nd Sept. 1983, 1983

Charcoal on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self Portrait 26th Sept. 1983

David Hockney

Self Portrait 26th Sept. 1983, 1983

Charcoal on paper

The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

© David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 30 Sept 1983

In the autumn of 1983, almost every day for two months, Hockney challenged himself to produce a candid self-portrait in charcoal. This period of intense self-reflection was, in part, a reaction to the untimely deaths of many of his friends due to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The vulnerability exposed in these drawings is a far cry from the confident self-portraits of thirty years earlier. Like the pages of a diary, these works record daily changes in the artist’s moods and emotions.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 30 Sept 1983, 1983

Charcoal on paper

Collection National Portrait Gallery, London

© David Hockney

Photography by Fabrice Gibert

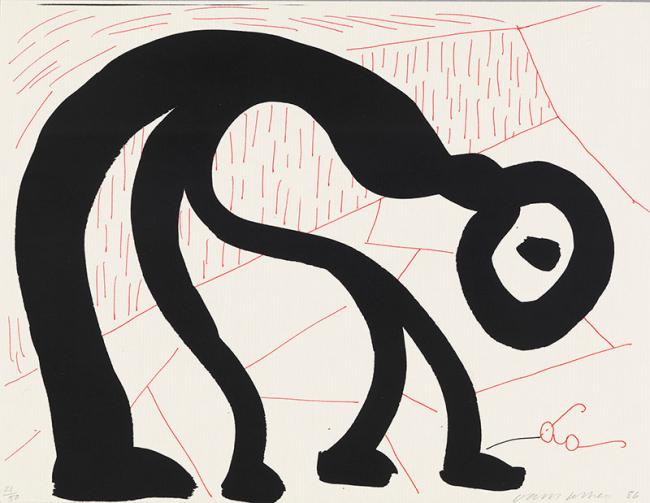

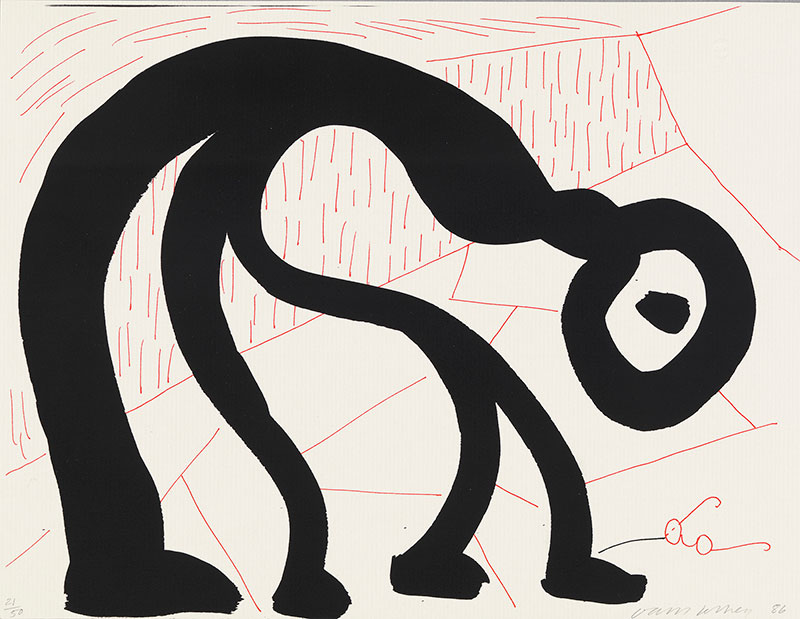

Man Looking for His Glasses

David Hockney

Man Looking for His Glasses, April, 1986, 1986

Homemade print

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

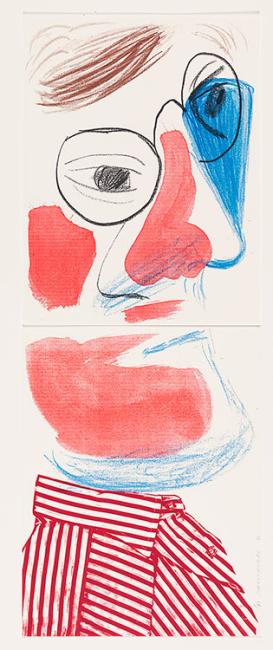

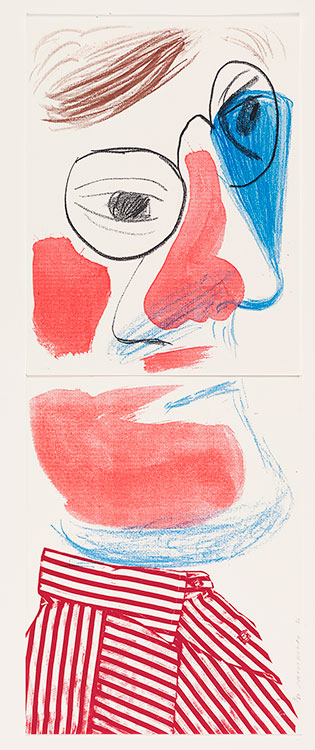

Self-Portrait, July 1986

In 1986, while working on designs for a production of Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde, Hockney began experimenting with a color laser photocopier to produce what he called "home-made prints." Replicating the traditional printmaking process, he repeatedly fed a single sheet of paper through the copier until each color of the drawing had been printed. In this self-portrait, he even placed his own striped shirt on the glass plate of the copier. Though created with modern technology, the prints have a playful directness that reveals the artist’s hand.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, July 1986, 1986

Homemade print on two sheets of paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Polaroid of Self-Portrait Drawing and Glasses (1–6)

David Hockney

Polaroid of Self-Portrait Drawing and Glasses (1–6), 1987

Polaroid

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 1988

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 1988

Crayon on sketchbook page

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

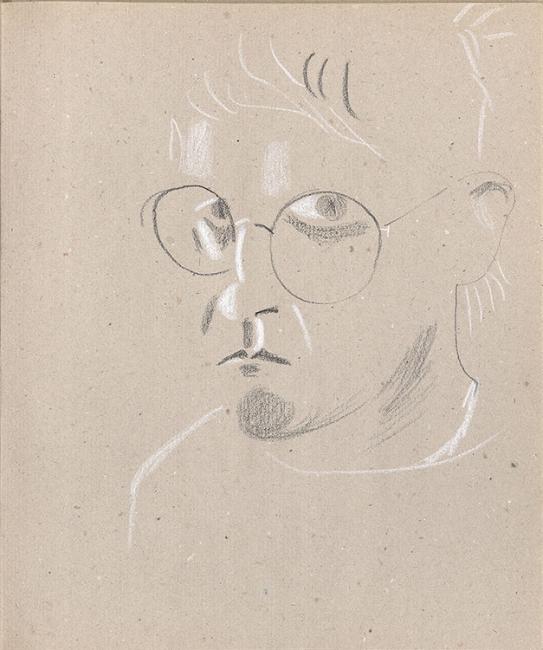

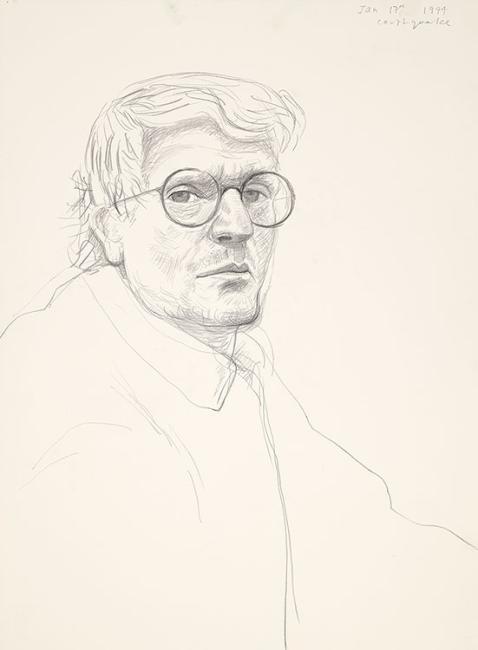

Self-Portrait (Earthquake), Jan. 17, 1994

The inscription on this sheet explains the artist’s weary look. Hockney, who lived in Los Angeles at the time, drew this self-portrait on the day the powerful Northridge earthquake struck the San Fernando Valley, northwest of the city—one of the most devastating earthquakes in United States history.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait (Earthquake), Jan. 17, 1994, 1994

Crayon on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self-Portrait, London, 3rd June 1999

Hockney has always made candid self-portraits in moments of introspection, tracking his own aging process. These playful drawings in which he displays different facial expressions, influenced by Rembrandt’s self-portrait etchings, can be seen as precursors to the iPad self-portraits.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, London, 3rd June 1999, 1999

Pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Steve Oliver

Self-Portrait, Baden-Baden, 10th June 1999

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, Baden-Baden, 10th June 1999, 1999

Pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self-Portrait, Baden-Baden, 10th June 1999

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, Baden-Baden, 10th June 1999, 1999

Pencil on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

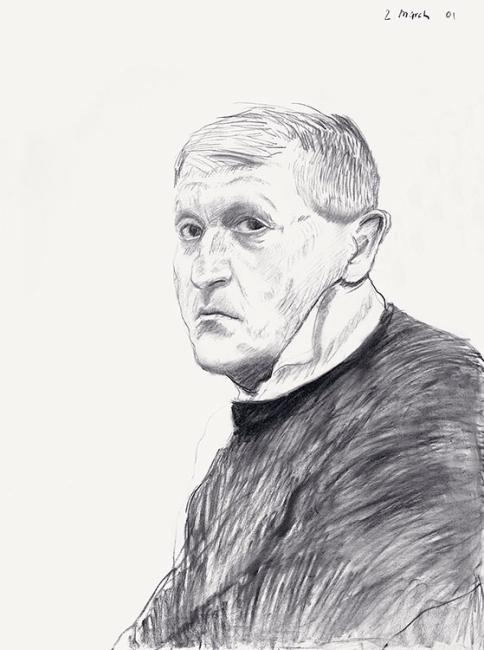

Self-Portrait, March 2 2001

The presence of the mirror frame in this drawing recalls a typical composition of Renaissance portraits in which the sitter is shown beyond a window ledge. Inspired by the extensive research he was conducting at the time into old master methods—notably the use of lenses and mirrors—Hockney adopted here the classical bust-length pose that is found in portraiture throughout European art history.

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, March 2 2001, 2001

Charcoal on paper

Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle. Purchased 2002 [am2002-281]

Françoise and Jean Frémon, Paris

© David Hockney

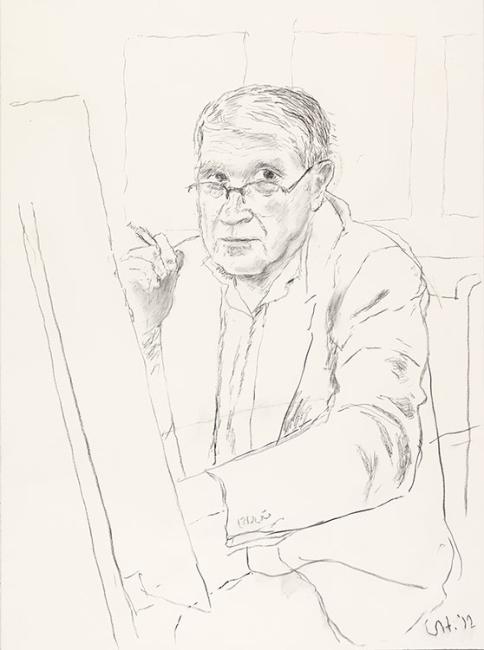

Self-Portrait Using Three Mirrors

David Hockney

Self-Portrait Using Three Mirrors, 2003

Watercolor on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

'True Mirror' Self-Portrait II

David Hockney

‘True Mirror’ Self-Portrait III, 2003

Ink and watercolor on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self Portrait with Red Braces

David Hockney

Self Portrait with Red Braces, 2003

Watercolor on paper

Collection Gregory Evans

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Self-Portrait, 17 Dec. 2012

David Hockney

Self-Portrait, 17 Dec. 2012, 2012

Charcoal on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

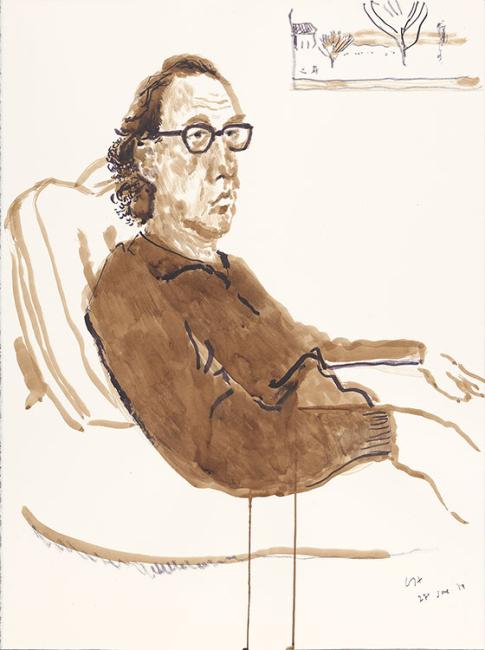

Recent Portraits of Gregory, Celia, and Maurice

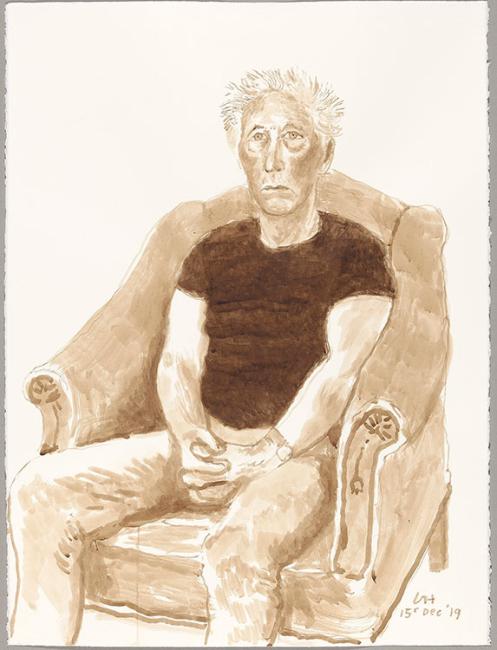

In the spring of 2019, Hockney traveled to Amsterdam for the opening of Hockney – Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature, an exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum. While there, he fell in love with Rembrandt again. Later that year, with Rembrandt and Van Gogh on his mind, and spurred by the prospect of the present exhibition, Hockney invited Celia, Gregory, and Maurice to sit for a new drawing series. In these three-quarter-length portraits, he paid particular attention to faces and hands, often his starting point. Drawn in Los Angeles and Normandy, where Hockney had recently moved, the portraits are fond evocations of time spent together and represent the many familiar faces and expressions of his old friends. Using Japanese brushes with integral reservoirs and the walnut-brown ink favored by Rembrandt, Hockney achieved an uninterrupted line and built up the portraits in three different tones.

Gregory Evans I

David Hockney

Gregory Evans I, 27 June 2019, 2019

Ink on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Maurice Payne, 16th Dec 2019

David Hockney

Maurice Payne, 16th Dec 2019,

Ink on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Gregory Evans II

David Hockney

Gregory Evans II, 27 June 2019, 2019

Ink on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

Celia Birtwell

David Hockney

Celia Birtwell, Nov. 21 2019,

2019

Ink on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Jonathan Wilkinson

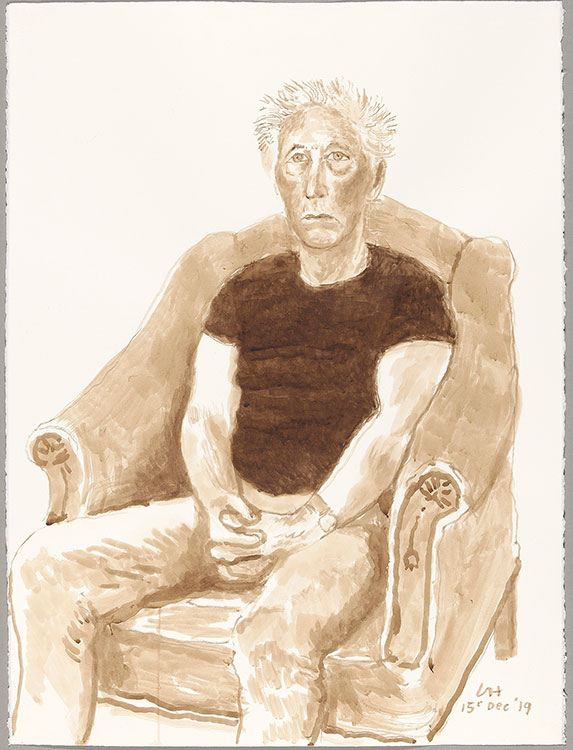

Maurice Payne, 15 Dec 2019

David Hockney

Maurice Payne, 15 Dec 2019, 2019

Ink on paper

Collection of the artist

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

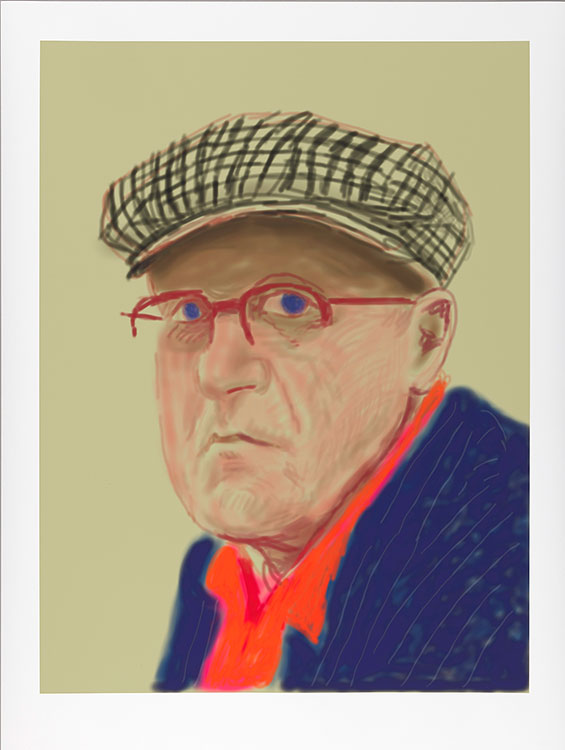

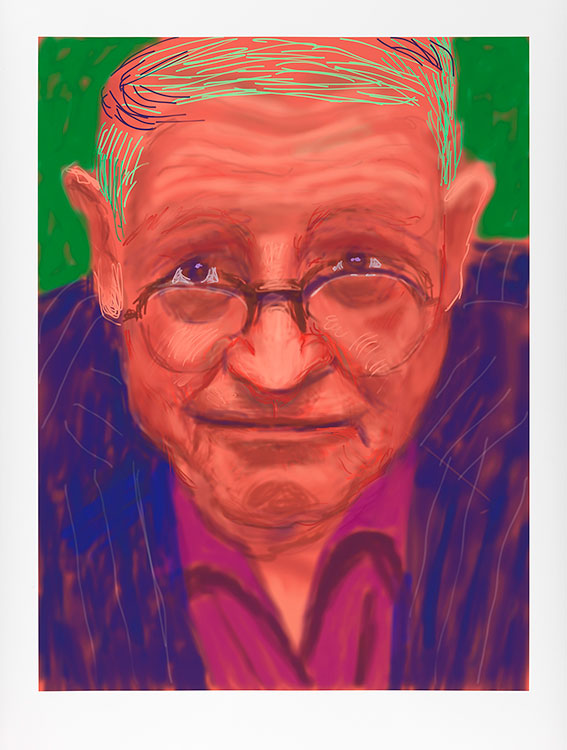

iPad Drawings

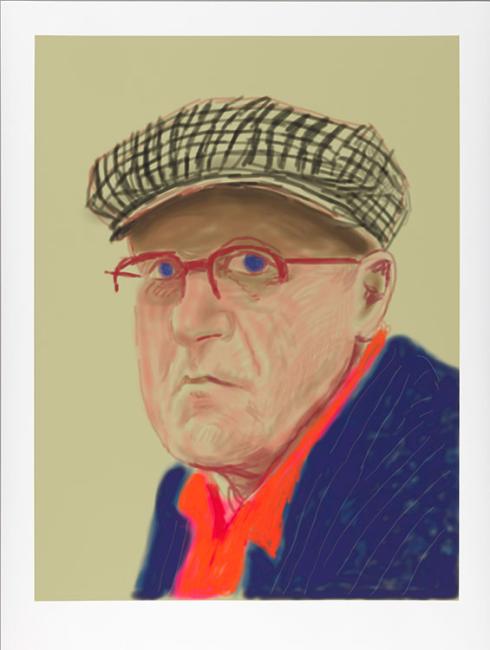

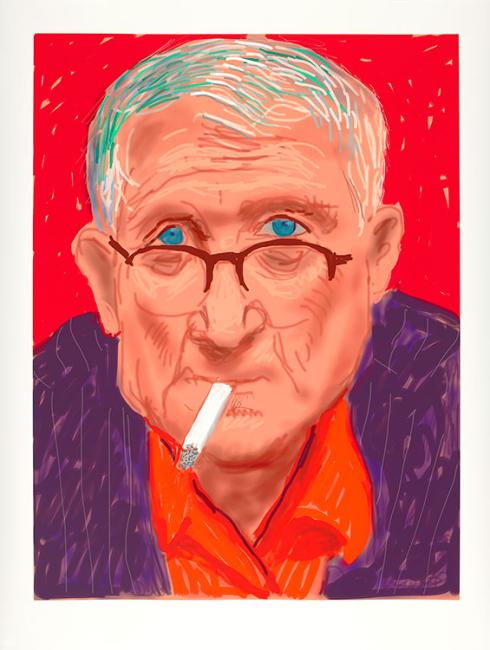

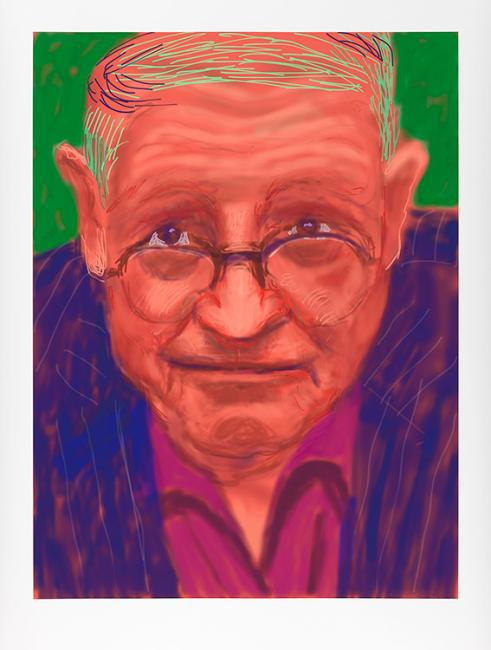

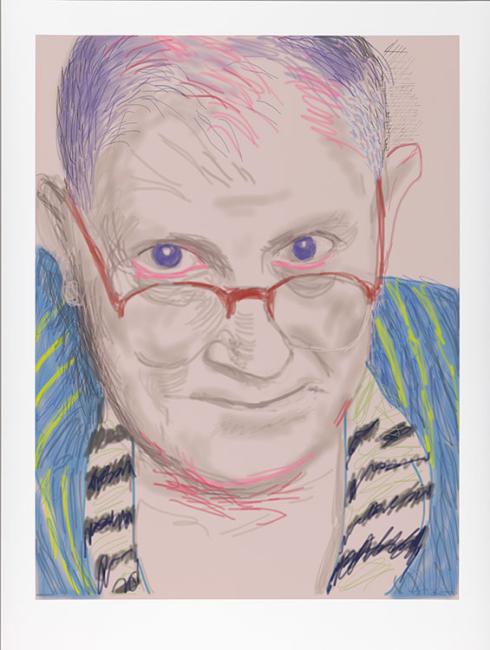

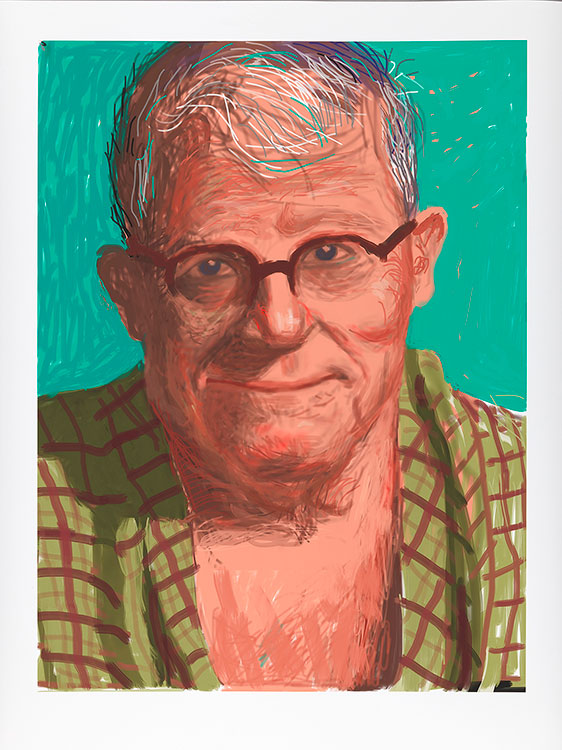

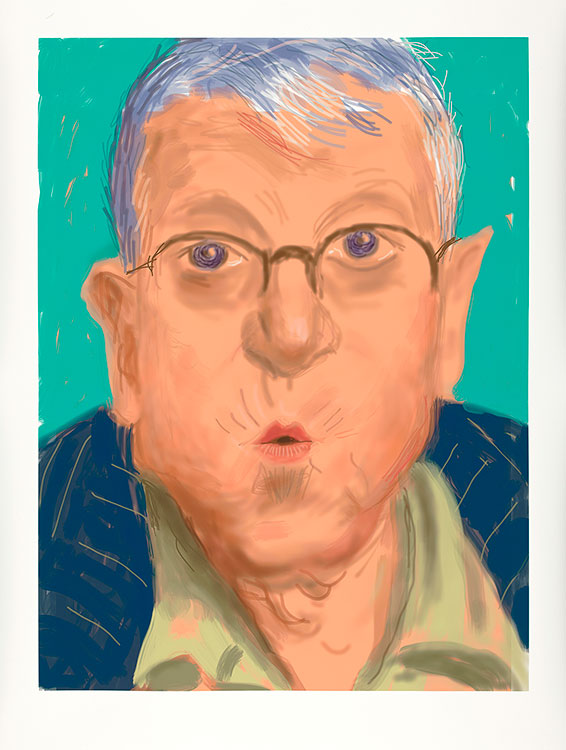

“I love new mediums. . . . I think mediums can turn you on, they can excite you: they always let you do something in a different way, even if you take the same subject.” In 2008, Hockney turned to Photoshop. At the same time, he began working on a smaller scale with the new technology provided by the iPhone and then the iPad. He employed the screen like a sketchbook, as a window with infinite possibilities for color and mark-making. He started out drawing with the side of his thumb, then took up the stylus when it became available. In 2012, Hockney made at least one digital self-portrait every day over the course of twenty days, exploring character types and facial expressions in a manner reminiscent of Rembrandt’s early self-portrait prints.

Artwork: © David Hockney

No. 384, 3 September 2010

David Hockney

No. 384, 3 September 2010 iPad drawing printed on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

No. 602, 11 December 2010

David Hockney

No. 602, 11 December 2010

iPad drawing printed on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

No. 1187, 9 March 2012

David Hockney

No. 1187, 9 March 2012

iPad drawing printed on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

No. 1196, 13 March 2012

David Hockney

No. 1196, 13 March 2012

iPad drawing printed on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

No. 1201, 14 March 2012

David Hockney

No. 1201, 14 March 2012

iPad drawing printed on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

No. 1218, 20 March 2012

David Hockney

No. 1218, 20 March 2012

iPad drawing printed on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

No. 1223, 21 March 2012

David Hockney

No. 1223, 21 March 2012

iPad drawing printed on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

No. 1223, 21 March 2012

David Hockney

No. 1223, 21 March 2012

iPad drawing printed on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt

No. 1231, 25 March 2012

David Hockney

No. 1231, 25 March 2012

iPad drawing printed on paper

The David Hockney Foundation

© David Hockney

Photography by Richard Schmidt