Morganmobile: It’s About Time

There's no escaping it: time is here to stay. No one can see it, hold it, slow it down or speed it up. But art can crystallize a moment, take the measure of the seasons, mark a recurring date, bemoan the ravages of aging—and derive a dirge, or delight, from time’s implacable passing.

Morganmobile: It’s About Time

This is one of the earliest manuscripts of the words we sing to mark the passage of one year and the dawn of a new one. Eighteenth-century Scottish poet Robert Burns wrote out the full text of “Auld Lang Syne” in a letter to a music publisher, claiming to have transcribed “an old song of the olden times” while listening to “an old man’s singing.” In the Scots language, the words of the song’s title mean old, long, and since. Combined, they mean, loosely, “time gone by” or “for old time’s sake.” The Burns version has become an international anthem of nostalgia, fellowship, and love.

Robert Burns (1759–1796), letter to George Thomson, September 1793. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1906. MA 47.27.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

According to tradition, Alexander the Great, accompanied by the saintly prophet, Khizr, traveled to the land of eternal darkness to find the spring of immortality. This image shows Khizr and Ilyas, who stumbled on the spring by chance. After dropping a dried fish into the pool and seeing it revive, the pair bathed in its waters and gained everlasting life. Although the silver pigment has oxidized, turning black over time, the resuscitated fish can still be seen swimming in the miraculous spring.

Niẓāmī, Khamsa (“The Quintet”), in Persian, Qazvīn, Iran, copied ca. 1549–51, illuminated ca. 1579, MS M.836, fol. 116r. Gift of the Estate of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

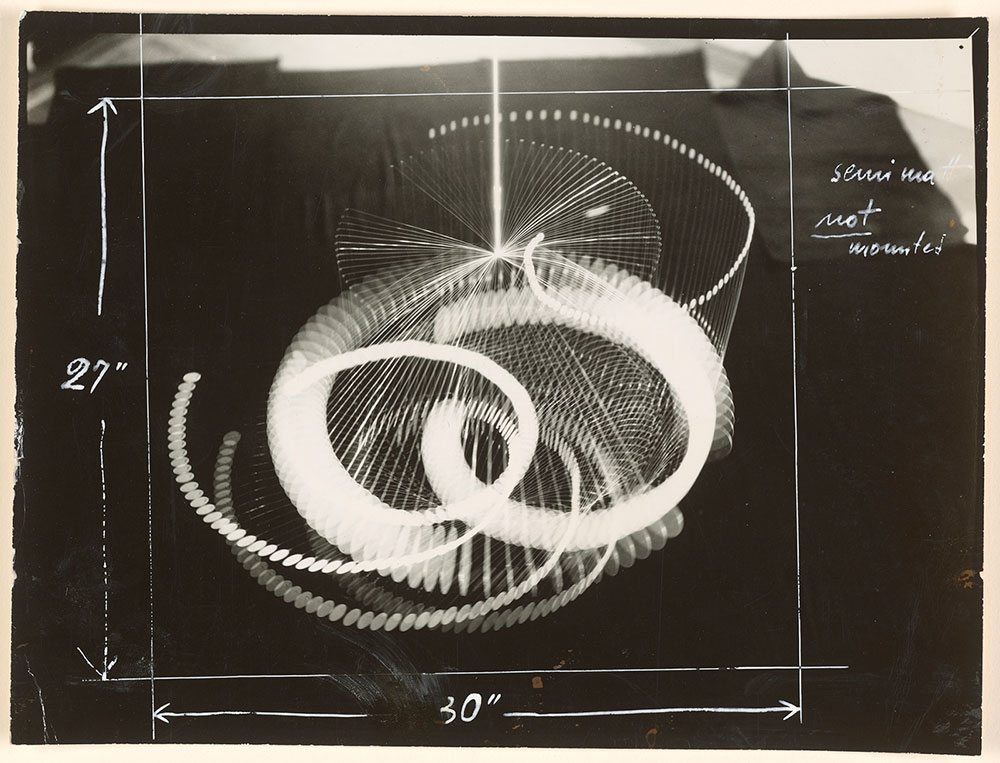

Alexander Calder’s suspended mobiles of articulated wire and sheet metal reconfigure themselves constantly under the gentle influence of air currents. In 1936, Herbert Matter captured the changing nature of a mobile in still photography by using the then-new technology of stroboscopic lighting. In this exposure of a few seconds’ duration, over one hundred regularly timed pulses of light map the movements of eight metal discs. Look outside the crop marks on the print to see how Matter achieved an illusion of bright, planet-like bodies floating in infinite black space. Adopting a high vantage point, he looked down at the mobile, which hung above a floor covered in bolts of dark fabric.

Herbert Matter, Alexander Calder suspended mobile in motion, 1936. Gelatin silver print inscribed in white ink. Purchased as the gift of Richard and Ronnie Grosbard, 2016.162.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

Symbolic and historical imagery crowds this depiction of winged Time laying Truth bare before a Dutch ambassador. Engraved above Time’s hourglass is a motto: I consume all things and sett foort[h] the Truth. Though personified as a woman, Truth represents the ghost of Isaac Dorislaus (1595–1649), a Dutch academic at Cambridge who had played a role in the prosecution of Charles I (1600–1649). Shortly after the king’s execution, Dorislaus was killed by royalists while visiting his homeland. His murder became a lightning rod for royalists and republicans alike and continued to be invoked, as here, in propaganda for the Anglo-Dutch War. That Time would implacably reveal the Truth was an ambiguous message: most copies of this engraving were issued with competing interpretations in English and Dutch.

Unrecorded artist, Dr. Dorislaw’s Ghost, Presented by Time to Unmask the Vizards of the Hollanders; and Discover the Lions Paw in the Face of the Sun, in this Juncture of Time……, [London], [printed by R.I. for T. Hinde, and N. Brooke], [1652]. Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987. PML 145850.25.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

In the eighteenth century, naturalists laid the ground for modern understanding of geologic time: the reckoning of earth’s age through the study of rock layers and fossil records. Their new scientific vision informed the work of Swiss artist Caspar Wolf, who often joined geological expeditions into the Alps. In his topographically accurate yet highly picturesque studies he recorded glaciers, caves, waterfalls, and rock strata, evoking the earth's great transformations over time. In this view, which juxtaposes two minuscule spectators—possibly scientists in the field—with an awe-inspiring waterfall, Wolf’s scientific interests are infused with a budding Romantic sensibility.

Caspar Wolf (1735–1783), Alpine Landscape with Two Figures Looking at a Waterfall from Under an Umbrella, ca. 1773. Opaque watercolor, 12 1/4 x 7 15/16 inches (312 x 203 mm). Thaw Collection, 2017.268.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

The subject of this scene is the cyclical nature of time. A farmer plows the ground. Before him grows the future plant ready to be reaped. His agricultural labors take place below symbols of the moon, the sun, and a group of seven stars. This constellation, known today as the Seven Sisters of the Pleiades and to the Babylonians as Mul Mul (stars), heralded the beginning of the seasons for sowing and reaping. As the seal was rolled onto a clay document, the image would repeat, evoking the perpetual cycle of the seasons.

Ancient cylinder seal with modern impression: Man Prodding Ox Pulling Plow, Astral Symbols Above, Mesopotamia, Neo-Assyrian period (ca. 1049–609 B C). Black serpentine, overall: 1 7/16 x 5/8 in. (3.7 x 1.7 cm). Morgan Seal 653. Acquired by Pierpont Morgan sometime between 1885 and 1908.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

Like many of Pier Francesco Mola’s caricatures, this example has both universal and personal aspects. The man lying in bed, contemplating a skull and hourglass, can be understood as an Allegory of Time, of life passing and the inevitability of death. In this case, based on inscriptions in other drawings by Mola, the man can be identified. Niccolò Simonelli (1611–1671), a connoisseur and collector, was a friend and supporter of Mola, but he was also a famously difficult personality. There is surely a backstory to the drawing, but the precise events that engendered it are unknown.

Pier Francesco Mola (1612–1666), Allegory of the Passage of Time, ca. 1660. Pen and brown ink, 6 1/16 x 10 1/8 inches (155 x 258 mm). Gift of János Scholz, 1985.92.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

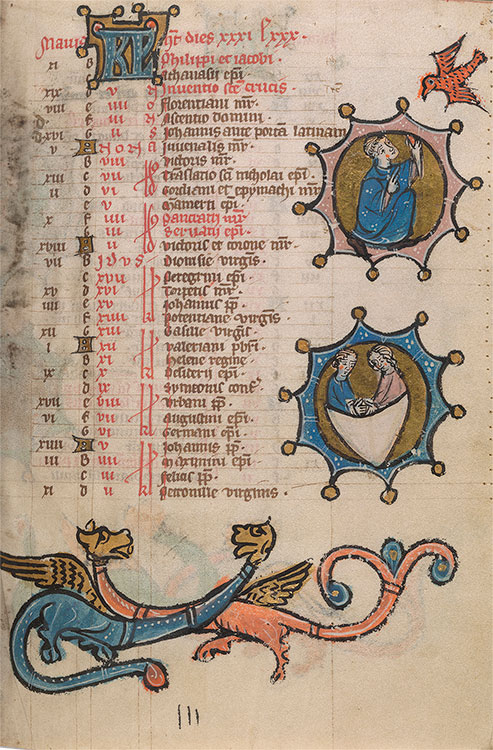

Unlike modern calendars, with their grids of empty days ready to be filled with engagements, medieval calendars came chock-a-block with data—to fill you in. The first two columns in this month of May (Maius, written at the top left) contain Golden Numbers and Dominical Letters for identifying the date of Easter, a movable feast. The next two columns contain the Roman calendar, with three fixed days: the Kalends (KL), Nones (Nonas), and Ides (Idus). Last come the feast days, the most important of which are written in red (hence our expression “red-letter day”); May 1 is the high feast of Saints Philip and James (Philippi et Iacobi). The month is illustrated with frolicking dragons and its particular Labor (hawking) and Zodiac sign (Gemini).

Psalter, in Latin and Dutch, Netherlands, Utrecht, ca. 1300, MS M.113, fol. 3.urchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913), 1907.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

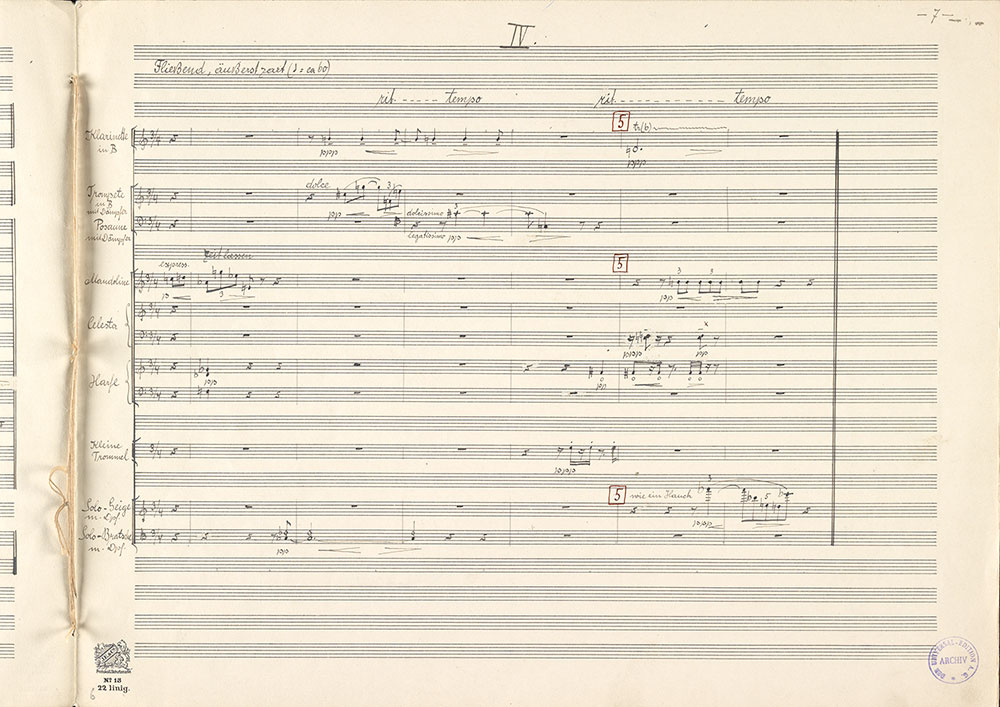

This is the shortest musical utterance of a composer known for very short pieces. Half a minute in duration and six measures long, the fourth movement of Anton Webern's Five Pieces for Orchestra Op. 10 epitomizes the art of brevity. In the preface to Six Bagatelles Op. 9, another very short work Webern composed around the same time, his teacher Arnold Schoenberg wrote: “Consider the restraint required to express oneself so briefly. Every glance can be expanded into a poem, every sigh into a novel. But to express a novel in a single gesture, joy in a single breath—such concentration can only be present when there is a corresponding lack of self-pity.”

Anton Webern (1883–1945), Five pieces for orchestra, op. 10, autograph manuscript, [1913]. Robert Owen Lehman Collection.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

Most of Ernest Hemingway’s early fiction manuscripts were stolen from a Paris train station in 1922. Ezra Pound responded to the news by remarking that the only thing Hemingway had really lost was the time it would take to rewrite the parts he could remember. If he failed to recapture stories he had created—if their forms “wobbled”—then they were never viable anyway. Whether the vignettes in Hemingway’s first published collection, in our time, reflect fresh starts or attempts at recreating his past efforts is unknown. The book’s title, deliberately set in lower case, suggests Hemingway's conviction that it was his time, dominated by the Great War, that had shaped both his experience and the language he needed to translate it into art.

Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961), in our time, Paris, Three Mountains Press, 1924. The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature. PML 185659.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

The handwritten caption reads: “When he was young, he could not imagine being old, and now that he is old, he cannot imagine ever having been young.” Duane Michals is ostensibly describing a third-person character (“he”), but the experience of aging he describes sounds firsthand. The seated man in his photograph, moreover, looks nothing like (nor notably older than) the “young” man whose painted likeness returns his gaze. These odd discrepancies, typical of Michals’s informal directorial style, only serve to underline his message: time makes us strangers to our youthful selves.

Duane Michals (b. 1932), When He Was Young, 1979. Gelatin silver print with manual additions. Purchased on the Photography Collectors Committee Fund, 2018.45.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

Channa Horwitz’s Sonakinatography drawings use notation and color to signify sound (sona) and motion (kina). The Los Angeles-based conceptual artist once observed, “As a painter I could compose in two dimensions, as a sculptress I could compose in three dimensions, but I could not understand how musicians and dancers could compose in the fourth dimension: Time.” This two-part score, rendered in colors (left) and numbers (right), was submitted as a proposal to the Laguna Beach Art Museum for an installation that would have been a quarter-mile long in space, eight days long in time.

Channa Horwitz (1932–2013), Sonakinatography I Fade Out Time Structure Composition III, 1972. Pen and ink and felt-tip pen on graph paper; two sheets, each 35 x 13 inches (89 x 33 cm). Gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee, 2019.100a-b.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

This coat-of-arms depicts three ages of man. Each figure—the young lover, the knight, and the old man—is accompanied by a Latin proverb concerning death. This unsigned armorial belongs to no individual or family. Its maker’s preoccupation with the passage of time and mortality is further evidenced by the inclusion, above and on the reverse of the drawing, of several passages related to death, drawn from Saint Augustine, Robert Holcot, and the Bible.

Imitatio Christi, Augsburg, Günther Zainer, [not after 1472]. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907. PML 17074.1, front endleaf recto.

Morganmobile: It's About Time

Simple yet ingenious, the hourglass was invented in the fourteenth century. The devices, which were cheaper than clocks and required no maintenance, were used to measure spans of time from a few minutes up to three hours. As grains of sand passed from one vial to the other, it was possible to see time slipping away. This Italian tarot card, from one of the most beautiful and complete fifteenth-century sets, shows Time personified as an elderly man. His white beard and stooped posture signal his venerable age, and his hourglass alludes to time’s passing.

[Bonifacio Bembo], Visconti-Sforza Tarot Card, Milan, Italy, ca. 1450–80, MS M.630.10. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan in 1911.