Morganmobile: Correspondence

To correspond: it can mean to match up or catch up, to reflect or to resonate. Oscar Wilde, Emma Goldman, the moon and an apple, a minor chord inscribed by Bach, and an illumination by Matisse figure among these collection treasures in which two come together as one.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

The Codex Huygens, a sixteenth-century manuscript by Carlo Urbino, includes drawings that explore harmonious correspondences between the proportions and motions of the human body. The Codex represents a kind of artists’ correspondence across time, too: Urbino's drawings are based on the writings of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). Urbino probably never met Leonardo and only knew his notebooks because Leonardo's artistic heir, Francesco Melzi, made the master's writings available to fellow artists.

Carlo Urbino (ca. 1510/20–after 1585), “Dezima figura,” fol. 27 of the Codex Huygens, ca. 1560–70. Pen and brown and red ink, and black chalk, inscribed with stylus and compass points, 186 x 133 mm. 2006.14:27.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

On her deathbed, Canace writes a sad letter to Machaire, her brother and lover. In the Greek myth, the siblings’ father, King Eolus, discovers his children’s incestuous affair when Canace gives birth to a son. Enraged, Eolus sends her a sword and demands that she kill herself. Before doing so, Canace, fearful that an equally dire fate awaits their son, writes to Machaire, asking him to bury the child in her grave, so he might mourn them together. In the miniature, while her son innocently looks on, Canace writes with one hand and stabs herself with the other; a satisfied Eolus stands nearby.

John Gower, Confessio amantis, in Middle English and Latin, England, London?, ca. 1470, possibly commissioned for Elizabeth Woodville, queen of England and wife of King Edward IV; MS M.126, fol. 51v (det.). Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913), 1903.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

The Letters of a Portuguese Nun is now known to be a work of fiction, but Henri Matisse and many of his contemporaries believed it to be a genuine account of unrequited love. Along with portraits of the lovelorn correspondent, Matisse designed lithograph ornaments for the chapter openings, each with a large calligraphic initial beneath a fruit or floral decorative motif. He spent sleepless nights on the task of drawing initials that would harmonize with the broad crayon strokes he used for the ornaments. “I know what a J is like now,” he confided to a friend, “and an A, the A is difficult … well, you shall see.”

Gabriel Joseph de Lavergne, vicomte de Guilleragues (1628–1685). Lettres [de] Marianna Alcaforado, lithographies originales de Henri Matisse. Paris: Tériade Éditeur, 1946. Frances and Michael Baylson Collection; PML 195603.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

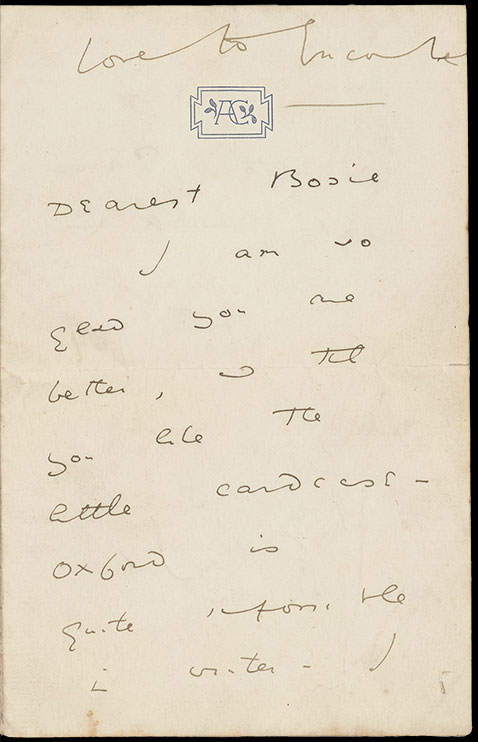

Written in November 1892 at a favorite haunt, the Albemarle Club, this is Oscar Wilde’s earliest surviving letter to his infamous lover, Lord Alfred Douglas (1870–1945). Wilde mentions his gift of a card case to Douglas, affectionately known as “Bosie,” and inquires about his recent illness in Oxford (“quite impossible in winter”). Perhaps thinking of his imminent travel to Paris and Bosie’s proposed trip to the Isles of Scilly, Wilde fantasizes about their slipping away together: “I should awfully like to go away with you somewhere—where it is hot and coloured.” The letter is a rare survival: after disavowing his relationship with Wilde later in life, Douglas destroyed much of their correspondence.

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900). Letter to Lord Alfred Douglas, [November 1892]. MA 7258.11. Gift of Lucia Moreira Salles, 2008.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

In the sonnet “Correspondences,” Charles Baudelaire grounds his liberating poetics in synesthesia—the merging and matching of diverse sensory impulses. The world, to him, is a forest of symbols: sounds, perfumes, and colors all correspond with an individual’s interior reality. The possibilities for language and significance are singular, therefore infinite: “all sing the raptures of the mind and of the senses.” When censors recalled the first edition of Les Fleurs du mal on the grounds of obscenity, they took no notice of the poem. Some literary critics, however, would come to view it as the most dangerous work in the book, due to its profound influence on younger poets such as Rimbaud and Verlaine.

Édouard Manet (1832–1883). Portrait of Charles Baudelaire, etching, 1865, in Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), Les fleurs du mal (Paris: Poulet-Malassis et de Broise, 1857). Gift of the trustees of the Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection, 1977. Heineman 40.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

Highly verbal from earliest youth, Duane Michals took up photography only in his late twenties; he did not unite the two forms of expression until he was forty-three. Upon his father’s death in 1975, Michals added a paragraph to a fifteen-year-old portrait of his parents and his brother. “As long as I can remember,” he wrote, “my father always said that one day he would write me a very special letter. But he never told me what the letter might be about. ... I knew what I hoped to read in the letter. I wanted him to tell me where he had hidden his affection. But then he died, and the letter never did arrive. And I never found that place where he had hidden his love.”

Duane Michals (b. 1932), A Letter from my Father, 1960 (image), 1975 (text). Gelatin silver print with manual additions. Gift of Duane Michals, 2019.78. © Duane Michals, Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

Reaching over the crenellated wall of his Roman prison, the Apostle Paul hands a sealed letter to Epaphroditus, who is about to return to his native Philippi. The letter, addressed to the congregation Paul founded in that Greek city, is full of gratitude and affection. He warns the Philippians of “enemies of the cross of Christ,” a phrase that likely inspired the illuminator to include a crucifixion in the scene. The thirteen New Testament letters traditionally ascribed to Paul are critical documents in the early development of Christianity.

Bible, Latin, Northeastern France, last quarter of the thirteenth century, MS M.969, fol. 420v. Purchased on the Fellows Fund in 1976.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

In the archives of writer and activist Emma Goldman (1869–1940), Andrea Bowers discovered the passionate love letters Goldman wrote to a physician and fellow radical, Ben Reitman (1879–1942). In this drawing, Bowers copied two lines from one of the letters: “Dearest heart of mine / You are my life / and all that it implies / sorrows, struggle / pain and despair.” Bowers produced the drawing by tracing the handwriting from a projection of a copy of the letter at 1:1 scale. The result is a detailed rendering, with the paper outline visible and every mark recorded. Bowers, whose work focuses on social justice, here explores the private side of a towering public figure.

Andrea Bowers (b. 1965), Excerpts from Emma Goldman's Love Letters "Sorrows, struggle, pain and despair.” Graphite, 12 1/4 x 9 1/8 inches (31.1 x 23.1 cm). Purchased on the Manley Family Fund, 2016.14. Image courtesy of the Artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York. © Andrea Bowers. Photography by Rebecca Fanuele.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

J. S. Bach worked within a Lutheran metaphysical tradition that heard religious truths reflected in music, with specific musical elements corresponding to certain theological ideas. The major chord, three sounds joined in one, was understood to manifest the Holy Trinity. Lowering the middle note of that chord one half step, to the more dissonant minor third, highlighted the human aspect of Jesus. In this way, a minor chord, like this B minor triad in an organ prelude, could remind listeners of humanity’s troubled place in the cosmos. Bach biographer Christian Wolff writes that the composer’s music “may epitomize nothing less than the difficult task of finding for himself an argument for the existence of God.”

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), Prelude and fugue for organ in B minor, BWV 544. Autograph manuscript, between 1727 and 1731. Robert Owen Lehman Collection, on deposit.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

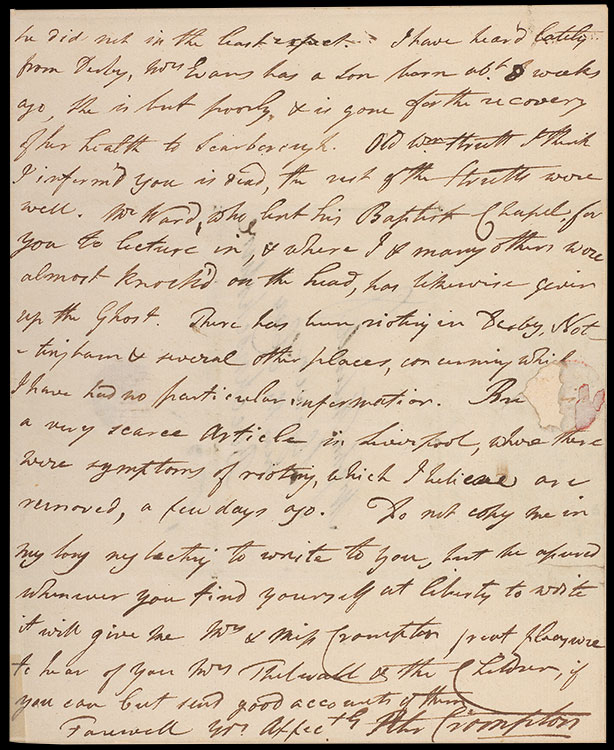

Historian E. P. Thompson identified John Thelwall (1764–1834) as “a significant link-figure between circles of advanced reformers and intellectuals in London and the provinces.” That role is attested by this letter to Thelwall in which a fellow reformer, Peter Crompton, describes a recent visit from poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and alludes to riots over the price of food in Derby, Nottingham, and Liverpool. Thelwall was a leader of the London Corresponding Society, which was dedicated to the reform of the British political system, including the expansion of the vote. He was spied on, tried for treason, and jailed for his political activities, and his lectures were often scenes of violence initiated by loyalists.

Peter Crompton (active 1796–1812). Letter to John Thelwall, Liverpool, 1800 September 11. MA 77.19, page 3. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan from J. Pearson & Co., 1904.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

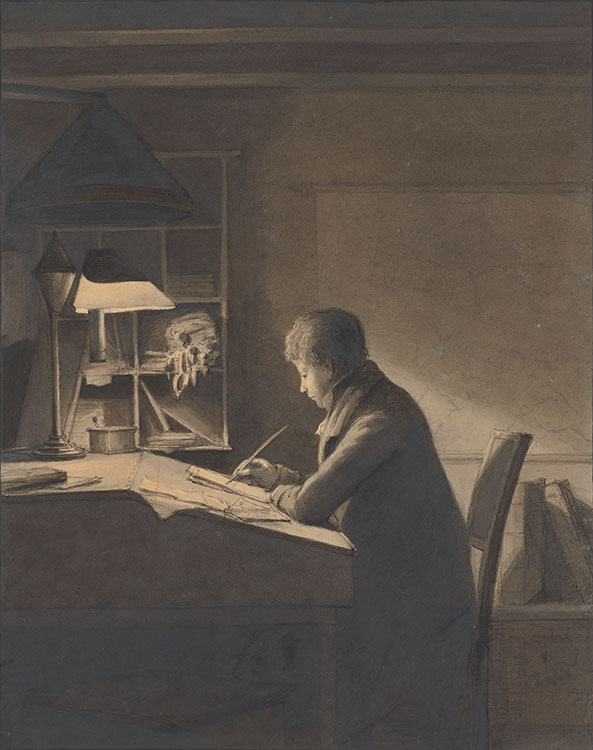

In this quiet nocturnal scene, a young man attends to his correspondence by lamplight. A pile of documents affixed with seals and the shelf of large volumes at right suggest that the setting is a notary clerk’s office rather than a private study. Despite the scene’s intensely introspective character, the large map that hangs on the wall behind the figure serves as a reminder of the world outside, which his letter will soon reach. Executed in Amsterdam in the early years of the nineteenth century, the drawing attests to the period’s fascination with earlier Dutch art and especially the work of the Delft painter Johannes Vermeer.

Johannes Jelgerhuis, A Young Man Seated at a Writing Desk by Lamplight, 1819. Black chalk and gray wash, 14 3/8 x 11 7/16 inches (36.5 x 29.1 cm). Bequest of Charles Ryskamp, 2010.47.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

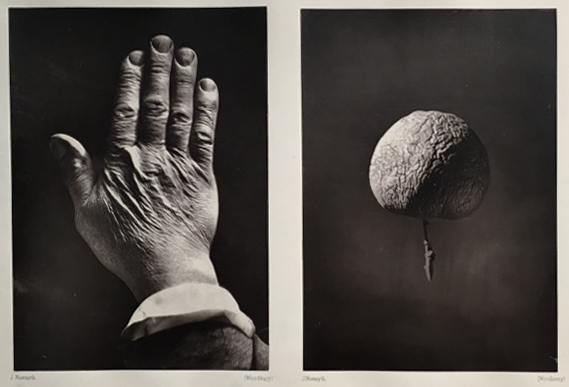

To make sense of the heavens, astronomers James Nasmyth and James Carpenter tried bringing them down to earth. Their photographically illustrated study of the moon (1874) advances several theories on “physiography”: the origins of lunar features visible through a telescope. In this pair of plates, photographer Nasmyth proposes understanding lunar “mountains” by an analogy—not to alpine topography on earth, but to wrinkles in the skin of people and fruit. The authors use the three-way visual correspondence to argue that a bygone epoch of surface saturation gave way, over time, to the dry, craggy formations observable on the present-day moon.

James Nasmyth (1808–1890), Back of Hand and Wrinkled Apple, to Illustrate the Origin of Certain Mountain Ranges, Resulting from Shrinking of the Interior. Plate 11 in James Nasmyth and James Carpenter, The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World and a Satellite. London: John Murray, 1874. Woodburytypes, 11.6 x 8.1 cm each, mounted to one leaf. Purchased as the gift of Peter J. Cohen, 2016.25.

Morganmobile: Correspondence

A pervasive feature in ornament is symmetry: formal correspondences arranged around an axis. Antoine Watteau’s working drawing exhibits little agreement between left and right—but it was not meant to be read as a whole. The engraver Gabriel Huquier used the sheet to make two prints: one illustrating the Temple of Diana, featuring the trellis with male herms seen at left, and the other devoted to the Temple of Neptune, using the masonry arch on the right. If one holds the sheet against a mirror along its vertical axis, each of Watteau’s half-designs is completed by its corresponding mirror image.

Antoine Watteau, Arabesque Design, ca. 1715–16. Red chalk. Purchased on the Sunny Crawford von Bülow Fund 1978, 1980.9.