Morganmobile: Beginnings

Everything starts somewhere, be it through gestation, an inventor’s trial-and-error, or lucky happenstance. Whether in the opening words of a manuscript, the public debut of a new expressive medium, or the creation myths of religion, beginnings point to what’s ahead.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

Photography debuted before the public twice in January 1839, with rival announcements in Paris and London introducing Louis Daguerre’s metal-plate process and William Henry Fox Talbot’s paper negative, respectively. Three months later came a less heralded, equally momentous event: the first reproduction of a photograph on a printed page. To illustrate an article on the utility of the new invention for botanists, Golding Bird exposed three fronds of fern in contact with a sensitized block of wood. The image was then carved into the block to produce an ink-bearing matrix, from which this cover plate was printed. Coincidentally, this issue of The Mirror also bears the first commercial advertisement for a camera.

Fac-Simile of a Photogenic Drawing on the cover of The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, April 20, 1839. London: Printed and published by J. Limbird. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, 2020.9.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

This highly finished drawing depicting the arrest and torture of Florentine Saint Minias (better known by his Italian name, San Miniato) represents two beginnings. A major monument of early Italian draftsmanship, it is one of the very few surviving drawings from the fourteenth century that can be connected to the work of a fresco painter. At the Morgan, moreover, it carries the inventory number I,1, identifying it as the first drawing in the original sequence of inventory numbers for the drawing collection. It was part of the Fairfax-Murray collection of some 1700 sheets bought in 1909, which in one stroke established Pierpont Morgan as a major collector of European drawings.

Attributed to Cenni di Francesco di Ser Cenni, Two Scenes from the Martyrdom of St. Minias, ca. 1390–1410. Pen and brown ink and wash over metalpoint, with white and red opaque watercolor, on paper prepared with brown ground. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1909, inv. I, 1.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

William Blake’s poems “Infant Joy” and “Infant Sorrow” propose a dual conception of life’s beginnings. Happily cradled in a blossom, the newborn who christens himself Joy inspires a symbiotic happiness in his mother. Another infant describes birth as an abrupt leap into a dangerous world. He is inconsolable, likening himself to “a fiend hid in a cloud”—the cause of his mother’s pain and his father’s tears. Through stylistic nuances in the relief-etched lettering and overall designs, Blake reinforces the separateness of these alternate entries into the world and the divergent lives to come. This impression of “Infant Sorrow,” one of three examples in the Morgan’s collection, is taken from one of the few copies of the combined Songs that Blake left uncolored.

William Blake (1757–1827), Songs of Innocence. [London]: The author and printer W. Blake, 1789. Bequest of Tessie Jones in memory of her father, Herschel V. Jones, 1968, PML 58636. Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [London]: The author and printer W. Blake, [ca. 1795]. Purchased with the Toovey Collection, 1899, PML 954.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

This tale begins with its ending and ends with its beginning. “This is the House that Jack built. This is the Malt that lay in the House that Jack built. This is the Rat that eat [sic] the Malt that lay in the House that Jack built.” Each line adds a new preceding element—a Cat, a Dog, a Cow—always, eventually, leading back to the house. The house adorning this light-hearted musical setting looks, perhaps, grander than the simple nursery rhyme might lead listeners to imagine.

Mr. (James) Hook (1746–1827), This is the house that Jack built. London: A. Bland & Weller, [1798?], first edition. Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection, 2008.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

This ancient book, the oldest intact manuscript at the Morgan, marks a beginning in several ways. Its full-page depiction of an interlace Ankh, an Egyptian symbol of life, is one of the earliest Coptic miniatures, auguring a vibrant tradition of painting associated with the Christian populations of Egypt. In format, the manuscript reflects the shift in late-antique book production away from scrolls toward the codex, in which gatherings of leaves are sewn together and bound between covers—a format still familiar to modern-day readers. Finally, the text is among the earliest substantial witnesses to the biblical book of Acts, which provides an account of the spread of Christianity immediately following Christ’s Ascension.

Acts of the Apostles, in Coptic. Egypt, late 5th century. MS G.67, fols. 214v-215.Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection in 1984.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

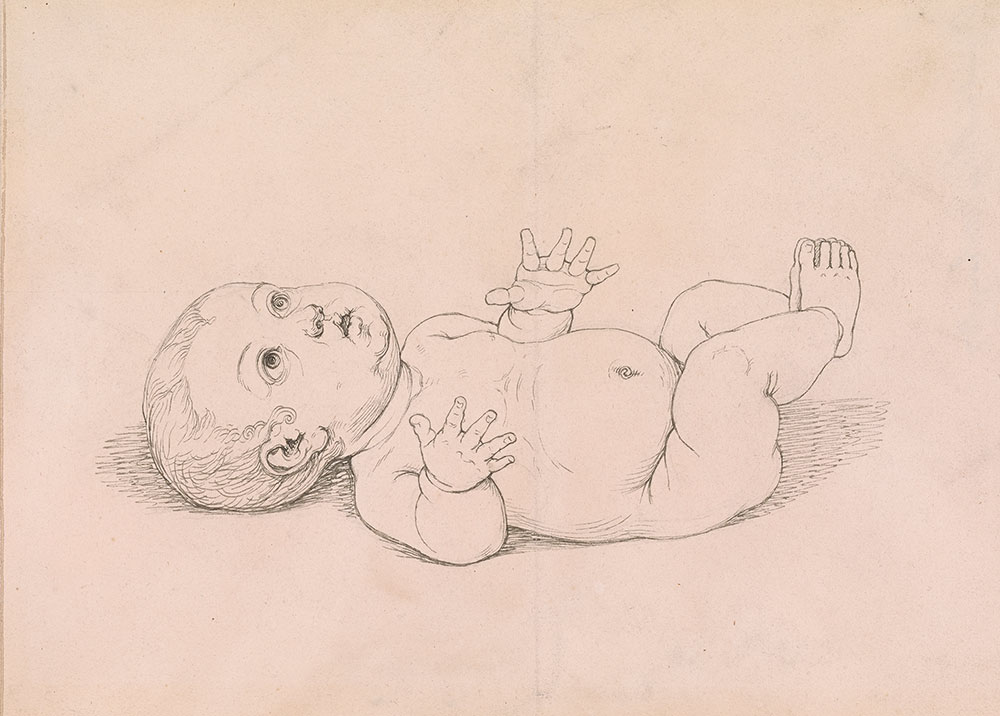

One of the key figures in the Romantic movement, Philipp Otto Runge developed a highly idiosyncratic pictorial language to convey his vision of harmonious unity among humanity, nature, and the divine. In 1802, he began developing ideas for a cycle of images in which flowers, children, and light would symbolize the Times of Day. In this preparatory study for Morning, executed in Runge’s reduced, highly linear style, the infant gazes upward, hands parted in wonder and feet pressed together as if in prayer. Helpless yet awake and alert, the child both witnesses and embodies the beginning of a new day.

Philipp Otto Runge, The Child, 1809. Pen and black ink over black chalk, 5 13/16 x 8 1/16 inches (147 x 205 mm). Thaw Collection, 2017.230.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

In the Epic of Etana, the titular shepherd king—the first monarch to rule after the great flood—is tasked with repopulating the ravaged earth. To obtain the plant of birth for his childless wife, he flies to heaven on the back of an eagle. On this cylinder seal, Etana appears on the eagle, its wings fully extended in flight. With less than two inches of vertical space in which to work, the artist was able to suggest the eagle’s upward movement by placing two sheep dogs on the ground, looking up and barking. On either side of the scene, a shepherd raises an arm towards Etana, further focusing attention on the ascending bird.

Ancient cylinder seal with modern impression, Etana’s Flight to Heaven on the Back of an Eagle. Mesopotamia, Akkadian period (ca. 2334–2154 B.C.). Serpentine. Overall: 1 7/16 x 1 1/8 in. (3.7 x 2.8 cm). Morgan Seal no. 236. Acquired by Pierpont Morgan sometime between 1885 and 1908.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

“In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth,” begins the story of Creation in the book of Genesis. The six days of Creation converge in this miniature portraying the sun, moon, stars, plants, birds, animals, and Adam and Eve. Within the walled Garden of Eden, a fountain sends forth the Four Rivers of Paradise. God, flanked by angels, blesses his work. At left, in a backstory to Creation, the rebel angels fall to earth, losing their robes and heavenly bodies to become hideous demons. Their influence on the subsequent narrative is intimated by the tall gate at the right. Through it, the first man and woman, having sinned, will be expelled from terrestrial Paradise.

Literal and Moral Commentaries on the Old Testament, in Latin. Belgium, Bruges, 1467, illuminated by the workshop of Willem Vrelant, MS M.535, fol. 4v (det.). Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1910.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

The title page for the first volume of the medieval romance Lancelot du Lac, printed shortly after 1500, reads: Le premier volume de lancelot du lac nouvellement imprime a Paris (“The first volume of Lancelot du Lac newly printed in Paris”). Early title pages were often quite spare: this one bears no author’s name, publisher, or date. The large, decorative initial L is meant to catch the eye of interested readers, just as illustrated book covers do today. Early English owners Edmond Harvye and Edmond Clerk wrote their names at the top of the page, and another reader added a four-line English poem about love below the title.

Lancelot du Lac, 3 volumes. Paris: Anthoine Vérard, after 1503. Purchased in 1929, PML 26582–84 (ChL 1549).

Morganmobile: Beginnings

A first date? Two young lovers, dressed in their Sunday best, are seated on a park bench. The initials carved into it record a succession of previous amorous encounters. Although he has his arm around her shoulders, the figures’ stiff pose expresses indifference and estrangement, a characteristic of Mammen's cynical depictions of heterosexual couples. Published in the popular satirical magazine Simplicissimus in 1930, this drawing is typical of her illustrations of Berlin city life.

Jeanne Mammen (German, 1890–1976), The Joy of Nature, ca. 1930. Graphite pencil and watercolor on paper, 17 x 14 1/8 inches (43.2 x 35.8 cm). Bequest of Fred Ebb, 2005.145. © Jeanne Mammen/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

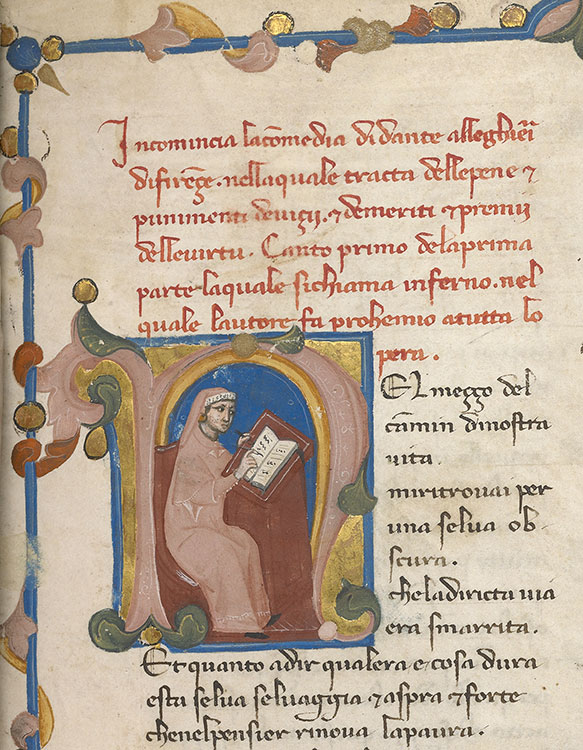

Dante is writing the Divine Comedy. Sitting at a lectern with his pen poised above an open book, the poet is nestled within a large initial N. The N is the first letter in “Nel,” the first word of Canto 1 of Inferno: “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita” (“Midway on our life’s journey”). The heading inscribed above reads: “Here begins the commedia of Dante Aligheri of Florence.”

La Divina commedia, in Italian. Florence, Italy, 1330–37, MS M.289, fol. 1r. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1907.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

By the age of thirteen, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was already studying to become an artist at the Toulouse Academy. This portrait roundel dates to the very start of his career, around 1793–94, which coincided with the Reign of Terror. Ingres carefully depicted the young nephew of the politician Jeanbon Saint-André (1749–1813), who, like the artist, was from Montauban. The boy’s Jacobin bonnet and jacket align him with his uncle, then at the peak of his engagement with the Revolutionary cause.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), Portrait of a Boy. Graphite. Purchased on the Sunny Crawford von Bulow Fund, 1978, 1982.2.

Morganmobile: Beginnings

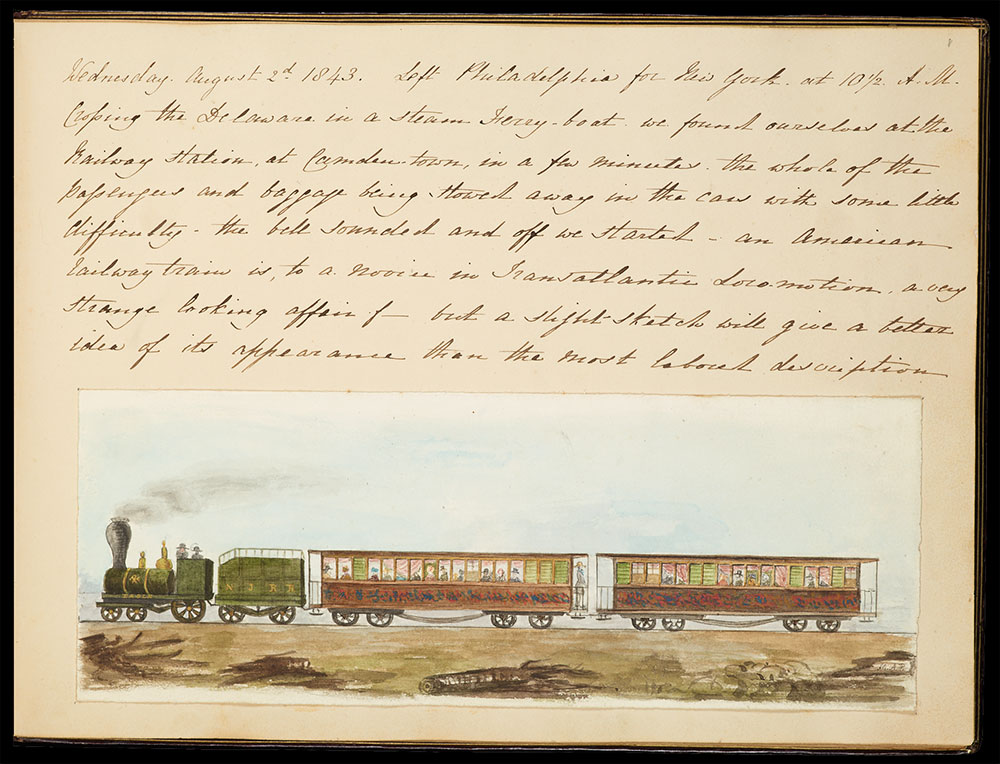

This page marks three beginnings: the opening lines of a new diary, the first day of a journey, and, most momentously, the start of a marriage. Mary Ann Hamilton of Philadelphia married Septimus Palairet of Bradford-on-Avon, England, in 1843, and together they embarked on a honeymoon tour of the eastern United States and Canada. In the collaborative diary of their travels, Mary Ann contributed the text and Septimus the illustrations. Here, they documented the steam locomotive Eagle, which carried them north from Camden, New Jersey. By the end of the trip, which would take them all the way to Niagara Falls, the Palairets experienced still another beginning: Mary Ann was expecting their first child.

Diary of Mary Ann Hamilton Palairet and Septimus Palairet, 1843. MA 2244. Gift of Arnold Whitridge, 1962.