Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

We spend a third of life on the other side of consciousness. To the ancients, dreams meant a future foretold; to the Romantics, the soul’s yearning realized; to Freud, instinct unbound. Nightmare or pipedream, catnap or coma, sleep haunts the waking life of art.

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

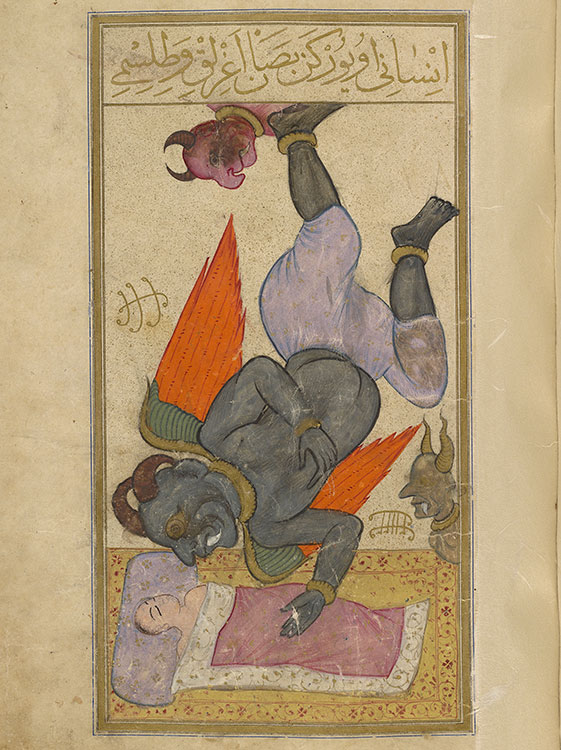

A sixteenth-century Turkish Book of Wonders at the Morgan contains three treatises, among them an illustrated compendium of demons, jinns, and their associated talismans. Here, the jinn Kabus (Nightmare) swoops down in hopes of ruining a man’s sleep. Kabus’s oppressive posturing reflects the belief that evil spirits cause nightmares by sitting on a person’s chest. The gold emblems on either side of Kabus represent talismans to be used for protection against the spirit. This manuscript was made for ʻAyisha Sultan, the daughter of the Ottoman Sultan Murad III.

Maṭāliʻ al-saʻāda wa manābiʻ al-siyāda (“The Ascension of Propitious Stars and the Sources of Sovereignty”), in Ottoman Turkish. Istanbul, ca. 1582. MS M.788, fol. 84r. Purchased in 1935.

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

In this gentle, quiet drawing, Rembrandt observes his wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh, asleep. Working relatively quickly in pen and brown ink, he first sketched the upper image. A tangle of twisty lines of varying thickness and intensity coalesce into a description of a weary female body sunken into a bed. The study below captures a slight, barely perceptible change in Saskia’s pose: her right arm has moved closer to her body, and the positions of her hand and fingers have changed.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606–1669), Two Studies of Saskia Asleep, ca. 1635–1637. Pen and brown ink and wash, on laid paper; traces of framing line. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan in 1909, I, 180.

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

Dreams—universal in human experience, yet subjective and immaterial—present a challenge for visual art. Cinema and photography can register the uncanny “realness” of dreaming, but slumber conjures realities to which the camera enjoys no access. In 1930s Paris, a milieu deeply informed by the Surrealists’ devotion to the subconscious, both André Kertész and André Steiner photographed attractive models reflected in distorting mirrors. If the grotesques of earlier artists, such as Hieronymous Bosch, passed judgment on the state of the human soul, Steiner’s phantasms seem to have crawled straight out of fever dreams.

André Steiner (1901–1978), Anamorphose VII, 1933. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Photography Collectors Committee Fund, 2016.161.

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

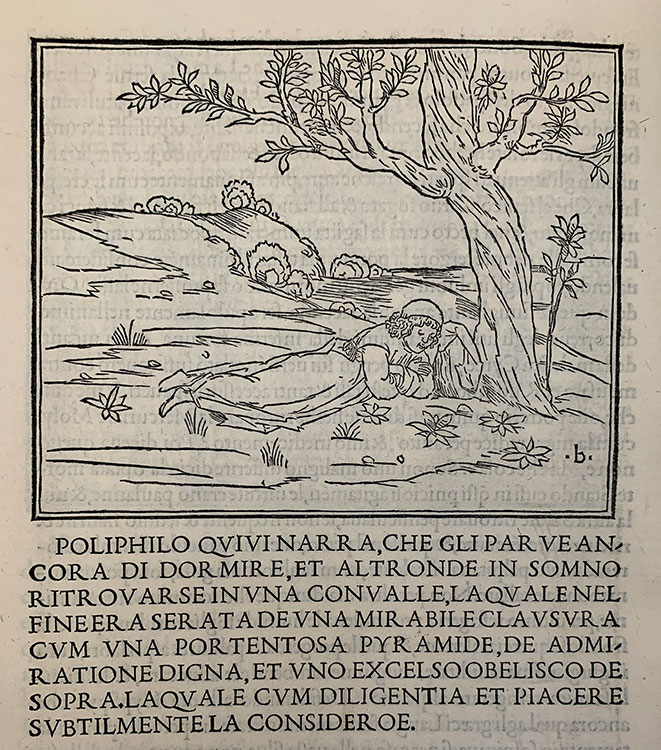

Love is strife. Or so asserts the title of the enigmatic Italian Renaissance epic Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, or The Strife of Love in the Dream of Poliphilo. Our hero, Poliphilo, falls asleep after being shunned by his love Polia, and dreams (and falls asleep to dream within the dream) of his fraught quest to attain her love. Ultimately compelled by Cupid, Polia returns Poliphilo’s love, only for Poliphilo to awaken alone.

Francesco Colonna, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Venice: Aldus Manutius for Leonardus Crassus, Dec. 1499. Purchased with the Irwin collection, 1900, PML 373.

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

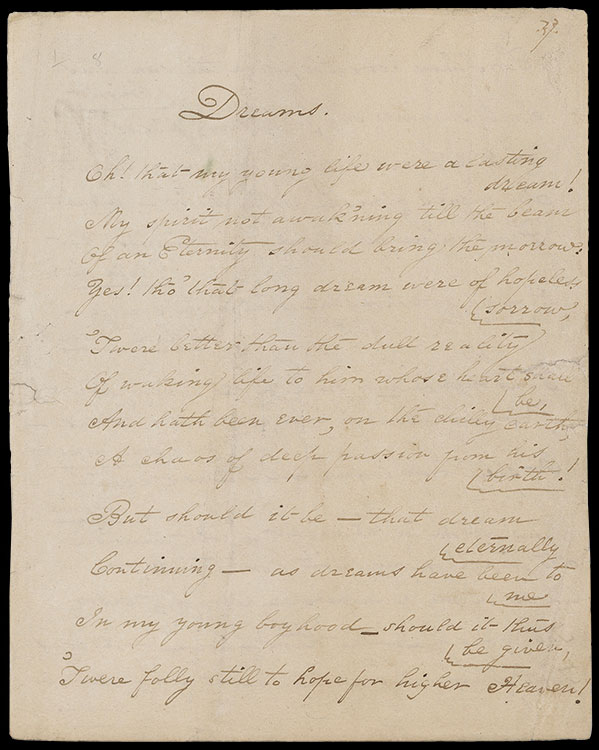

This poem appeared in Edgar Allan Poe’s first, extremely rare, collection, Tamerlane and Other Poems, published by the teenage poet in Boston in 1827. The narrator of the poem rejects “waking life” for the world of dreams, where he is in control, able to create “climes of mine imagining [...] beings that have been / Of mine own thought.” He admits that dreams can also resemble terrifying natural forces, describing one dream as a “night-wind” that “left behind / Its image on my spirit.” In his later fiction and poetry, Poe would delve fully into nightmarish realms.

Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), autograph fair copy of “Dreams,” circa 1827–1828. MA 644.1. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910.

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

This drawing is preparatory for an altarpiece depicting the ecstasy of the Blessed Ambrogio Patrizi (1266–1328). In line with the developing naturalism of early Baroque art, Manetti based his painted image of the monk on a life drawing—not of a monk in ecstasy, but of a youth posing in the studio, dressed in monk’s robes and apparently asleep against a pile of books.

Rutilio Manetti (1571–1639), A Life Study: A Monk Sleeping against a Pile of Books, 1616. Purchased on the Fairfax Murray Society Fund, 2019.102.

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

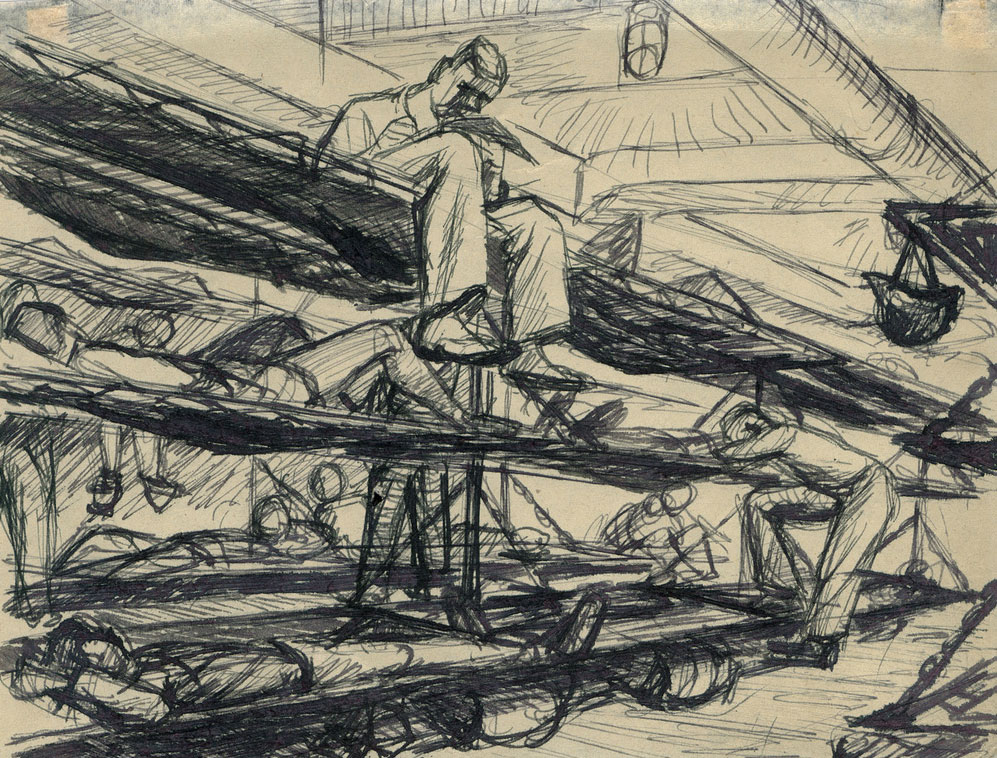

Drafted into the Army during World War II, Philip Pearlstein began recording the daily life of a G.I. in sketches he would send to his parents back home. While sailing in a convoy bound for Italy in 1944, he drew the ship’s sleeping quarters. Observing his fellow soldiers from the perspective of his own bunk, he made palpable the pervasive boredom of the fifteen-day crossing.

Philip Pearlstein (American, born 1924), Convoy to Italy IV, 1944. Pen and ink on paper, 4 11/16 x 6 3/16 inches (11.91 x 15.66 cm). Gift of Jane & David Walentas and Bruce Weber and Nan Bush, 2016.87. © Philip Pearlstein / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

In 1729, while preparing over sixty drawings for an illustrated 1738 edition of Miguel de Cervantes’s The Ingenious Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605–15), the artist John Vanderbank had an adventure himself, fleeing England for France to avoid debtors’ prison. In this scene from the novel, the sleepwalking Quixote, clad in a skimpy nightshirt, wields his sword in a heroic—but entirely imagined—battle with giants. The innkeeper and Quixote’s squire, Sancho Panza, raise their hands in alarm as they realize that the innkeeper’s wineskins have fallen victim to the knight’s swordplay. What Quixote perceives as the blood of giants is actually the inn’s store of red wine, seeping into the ground.

John Vanderbank (British, 1694–1739), Don Quixote Attacking the Wine-Skins in His Sleep, 1729. Brush and brown wash, with white opaque watercolor, over graphite, on paper tinted with a light brown wash. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan in 1909, 1975.17:17.

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

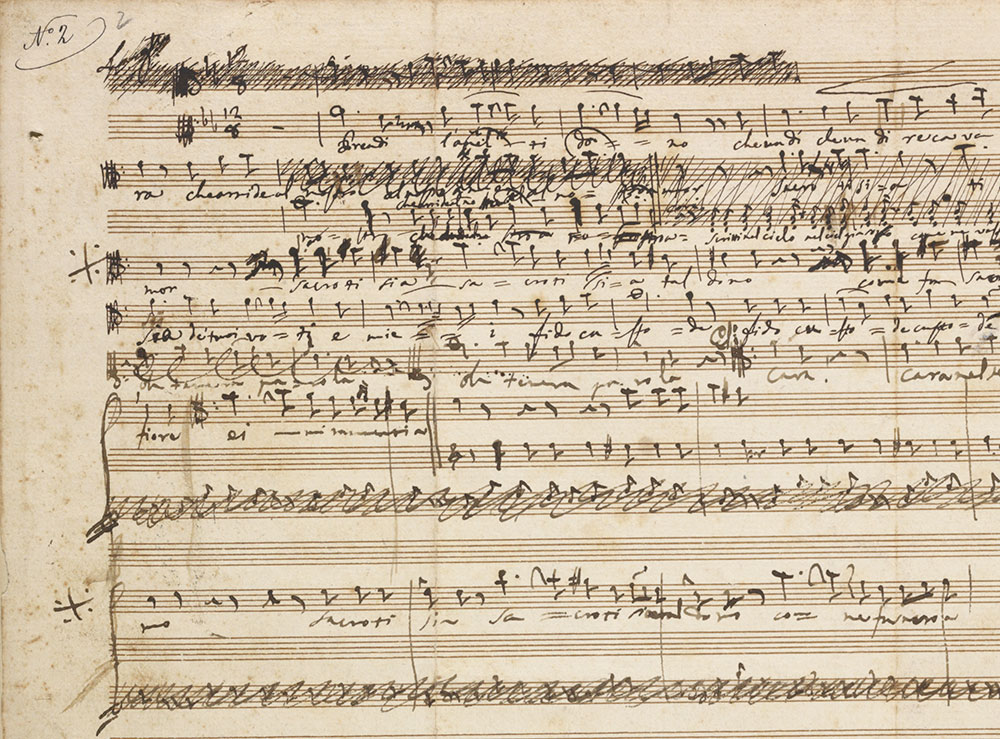

In the movies, sleepwalking usually lends itself either to horror or to comedy. Vincenzo Bellini's operatic treatment, La sonnambula, takes the humorous approach. Amina, engaged to Elvino, sleepwalks into the bedroom of the mysterious Count Rodolfo. The count honorably decides to leave without waking her, but when Elvino—not knowing Amina’s tendency to somnambulate—discovers her asleep in Rodolfo’s room, he calls off the wedding. Happiness is restored after he witnesses her, sound asleep, stepping precariously across a rooftop bridge.

Vincenzo Bellini (1801–1835), La sonnambula, Sketches and drafts for Act 1. Autograph manuscript, 1831(?), Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection.

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

Having discovered that his virgin wife, Mary, is pregnant with a child who is not his own, Joseph is disturbed. He threatens to abandon her—a course of action that risks upsetting God’s plans for the redemption of humankind through Mary’s son, Jesus. God dispatches the Archangel Gabriel to appear to Joseph in a dream and reveal the special nature of Mary’s child. Upon awakening, Joseph agrees to protect his wife and help raise their future child. Joseph’s Dream, though rarely depicted in art, occupies a full page in this Gospel Lectionary. In the High Middle Ages the liturgical year began on Christmas Eve, and Matthew’s account of Joseph’s repudiation and reconciliation opens this book.

Dream of Saint Joseph, from an Evangeliary, written and illuminated in Austria at the Monastery of St. Peter in Salzburg by Custos Perhtolt, 1070–90. MS M.780, fol. 1v. Purchased on the Lewis Cass Ledyard Fund, 1933.

Morganmobile: Sleep, Dream

Oblivious to the world, King Chandana lies lost in slumber on his luxurious royal bed. Although his expression is serene, his sleep is interrupted by a vivid dream. The goddess Mātā appears before him and reports that the queen’s two brothers have abandoned civilization to go live in the forest. Chandana, resplendent in his striped gown and pearls, is shown twice in the miniature: dreaming of the goddess and then kneeling in supplication before her. The story continues on the back of the leaf, which depicts Queen Malayagiri’s bedchamber. Awakening her, Chandana tells her his dream, and she discerns its spiritual meaning: all attachment is illusion.

Two miniatures from the Chandana Malayagiri Vārtā (“The Story of Chandana and Malayagiri”), a Jain folk tale, Kishangarh, Rajasthan, India, ca. 1745–46, MS M.1060.3r-v. Gift of Paul F. Walter, 1984.