Betye Saar: Call and Response

One of the most significant assemblage artists active today, Betye Saar (b. 1926, Los Angeles) addresses themes of spirituality, gender, and race in her work. She is part of the strong Southern Californian tradition of creating art through found objects. For the past fifty years, Saar has combined items typically discovered at flea markets and secondhand stores into conceptually and physically elaborate creations. “Finding something old that has its memory has always been important to me,” she explains.

Saar’s creative process starts with a particular found object—a piece of leather, a cot, a tray, a birdcage, an ironing board. These objects are ordinary, used, slightly debased things most people would simply pass by.

After identifying a primary object that calls to her, Saar surveys her stockpile of other found materials to see what feels appropriate to combine with it. Once she has arrived at a vision of the final work in her mind’s eye, Saar responds with a sketch: “The sketch is to remind me how [a piece] is going to look when I get it put together.”

Saar has kept sketchbooks throughout her career, laying out quick visuals for works, jotting down ideas about materials, and noting potential titles for finished pieces. She has also kept more elaborate travel sketchbooks containing exquisite watercolors and collages. This exhibition offers the first public opportunity to view Saar’s sketchbooks and examine the relationship among her found objects, sketches, and finished works—illuminating, in the artist’s words, “the mysterious transformation of object into art.”

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California; Photo by Richard W. Saar

Betye Saar: Call and Response is organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The exhibition is curated by Carol S. Eliel, senior curator of modern art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The coordinating curator at the Morgan Library & Museum is Rachel Federman, associate curator of modern and contemporary drawings.

The exhibition is made possible with lead corporate support from Morgan Stanley and lead support from the Ford Foundation. Additional support is provided by Agnes Gund; Louisa Stude Sarofim; The Lunder Foundation – Peter and Paula Lunder family; Francis H. Williams and Keris Salmon; the Terra Foundation for American Art; and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.

![]()

![]()

Colin B. Bailey: Hello, I'm Colin B. Bailey, director of The Morgan Library & Museum, and I'm delighted to welcome you to Betye Saar: Call and Response. This exhibition puts on display for the first time Betye Saar's private sketchbooks, which she has kept throughout her career. As you will see, they are an important bridge from the found objects that call to her to the completed assemblages, which are her response. The audio clips you will hear on this tour come primarily from interviews and talks Betye Saar has given over the years, in which she discussed various aspects of her practice, from the art that influenced her to some of the events that galvanized her. They'll be introduced by Rachel Federman, Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Drawings at the Morgan. As you move about the gallery, look for the audio symbols to discover these clips. Thank you for joining us at the Morgan. We hope you enjoy your visit.

Overview

Gallery Images

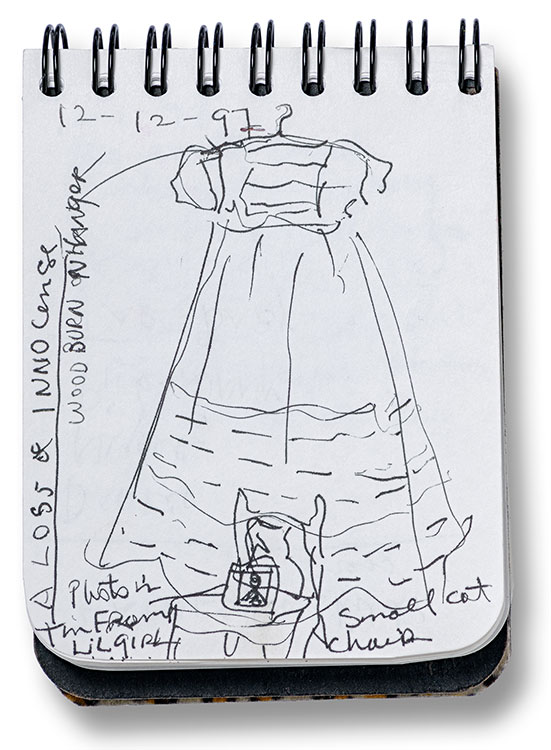

A Loss of Innocence

The labels sewn onto the dress in this tableau list various racial epithets for Black children, and the wooden hanger branded with the work’s title alludes to the marking of enslaved people with branding irons. This evocative installation suggests the fragile innocence that is lost—not only historically but also to this day—as Black children grow into adults facing racism in its many guises.

Betye Saar

A Loss of Innocence, 1998

Dress with printed labels, wood hanger, chair, and framed photo on block

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

Photo courtesy Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale, AZ, by Tim Lanterman.

Sketchbook pages for A Loss of Innocence

Betye Saar

Sketchbook pages for A Loss of Innocence:

19 April 1996

Ballpoint pen on paper pasted into sketchbook

12 December 1997 (facsimile)

Ballpoint pen on paper

1 March 1998 (facsimile)

Marker on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Eyes of the Beholder

Saar titled this work Tantric Tray in her related sketchbook drawing on view nearby, evoking the Tantric practice of eye gazing, a tool for opening oneself to a higher plane of consciousness. At the same time, the lozenges in the baking pan at center can be read as a dozen martinis with stuffed olives seen from above—a witty play on Saar’s

use of a cocktail tray for this assemblage.

Betye Saar

Eyes of the Beholder, 1994

Paint on metal and wood serving tray, with painted metal baking pan and metal ornaments

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Memory Window for Anastacia

Since the late 1960s, Saar has used discarded window frames like this one in her art. Here, she pays homage to a figure of legend venerated in Brazil: the blue-eyed, black-skinned Anastacia. Though expunged in the 1980s by the Brazilian Catholic Church, Anastacia was embraced by the local Umbanda religion, which combines aspects of Catholicism, Spiritism, and African and indigenous Brazilian belief systems. Copper coils on nails emerge from the window frame, suggesting psychic power or energy. The copper circuit boards used as a support evoke another form of energy generation and circulation.

Betye Saar

Memory Window for Anastacia, 1994

Paint on copper circuit boards in wood window frame, with metal ornaments and copper wire–covered nails

Private collection, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.© Betye Saar.

Robert Wedemeyer

Rachel Federman: Betty Saar's earliest found object assemblages from the 1960s used old window frames like this one. Two events in her life were particularly formative to her becoming an assemblage artist. As a child in the 1930s, she witnessed the construction of the Watts Towers in Los Angeles during weekly visits to her grandmother. Constructed by Simon Rodia between 1921 and 1954, the towers are a monumental work of folk art constructed from salvaged-steel rebar, cement, discarded bottles, and other detritus. Many years later, in January 1967, Saar visited an exhibition of works by Joseph Cornell at the Pasadena Art Museum. This is Saar speaking about it in 2011.

Betty Saar: The show was like a jewelry store because it was very dim, pin spots on each little box. It just really blew me away as much as the Watts Towers did in another way, you know, where the Watts Towers went up and out and encompassed all the junk that he glued on it. Here was a little box where all the junk was put right inside, which was another little magical world instead of like taking a pane from the window and making a little box and being able to go into that little box. So that started the assemblages.

Audio: Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Sketchbook pages for Memory Window for Anastacia and Eyes of the Beholder

Betye Saar

Sketchbook pages for Memory Window for Anastacia and Eyes of the Beholder, 3 May

and 6 November 1994

Watercolor and ballpoint pen on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Serving Time

The cultural historian George Lipsitz has commented on this piece: “The descendants of yesterday’s slaves and servants are not free; millions of them are serving time in jails and prisons while others are locked into low-wage jobs and locked out of upward mobility. By associating contemporary incarceration with historical slavery and Jim Crow segregation, Saar renders the cage as evidence of the oppressor’s cruelty rather than as a representation of the deserved fate of the oppressed.”

Betye Saar

Serving Time, 2010

Metal cage with stand, figures, keys, and locks

Collection of Neil Lane. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.© Betye Saar.

Robert Wedemeyer

Rachel Federman: In 1965, the predominantly African-American neighborhood of Watts was the site of an uprising. It was one of many uprisings around the country that reflected frustration with the persistent inequitable treatment of Black and brown communities. In its wake, the artists Noah Purifoy and others created art from the wreckage, displaying their assemblages in an exhibition called 66 Signs of Neon. Saar, who lived in Laurel Canyon with her three daughters at the time, was acutely aware of the Watts Rebellion. When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated three years later in Memphis, it marked a turning point in her work. This is Saar speaking in 2011.

Betye Saar: That was another crossroads for me, another place where my work really changed. It just seemed really terrible the way that was, and I began to not abandon the magical things, the occult things, but to really focus on the plight of Black people. And that's when I did, what, '72 that I did the Liberation of Aunt Jemima. And that just started me on investigating by recycling derogatory images of how Black people were traditionally depicted into making them heroes and to making them warriors and so forth.

Audio: Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

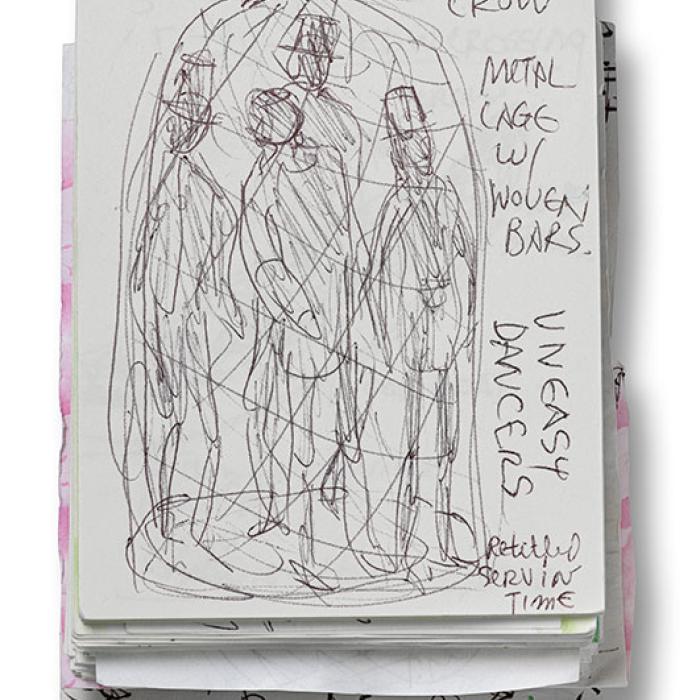

Sketchbook page for Serving Time

Saar identifies the bird atop the cage in this drawing as “(Jim) Crow.” Jim Crow laws were used to enforce racial segregation in the American South from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 to the beginning of the civil rights movement in the 1950s. The name supposedly derives from a nineteenth-century minstrel routine called “Jump Jim Crow,” which was performed by a white man in blackface; it eventually became a derogatory name for Black Americans.

Betye Saar

Sketchbook page for Serving Time, 24 February 2009 (facsimile)

Ballpoint pen on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

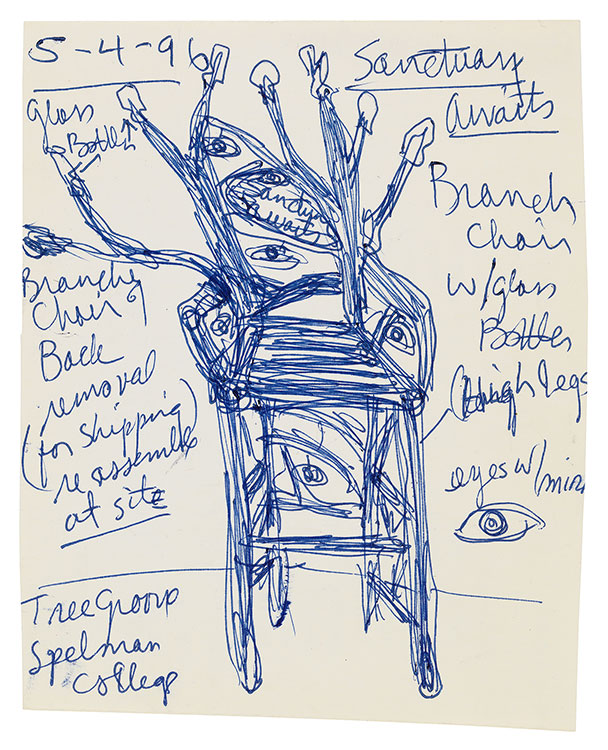

Sanctuary Awaits

Sanctuary Awaits is informed by the African Kongo tradition of bottle trees, which are garlanded with bottles, vessels, and other objects to protect a household. Black people in the Caribbean took up this tradition as early as the 1790s; it continues today in the southern United States, where many still believe that bottle trees ward off evil. Saar made this sculpture as one of a three-part piece exhibited in conjunction with the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta.

Betye Saar

Sanctuary Awaits, 1996

Wood, glass bottles, metal wire, palm fronds, compass, sheet tin, screws, and nails

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Rachel Federman: This is Betye Saar speaking in 2002 about the African tradition of the spirit bottle.

Betye Saar: It's like most or many metaphysical things. There's like the trickster, it's positive and negative. The glass attracts the negative image and it's captured in there. Also, it attracts the spirit that's positive to go and visit that house. And that custom came over to the United States, and still in parts of the south. They have trees where bottles are out there to either Robert Farris Thomas wrote about the flash of the spirit. That's what it is, the sun or the light reflecting on the glass for the spirit to attract a benevolent spirit to repel or capture a negative spirit.

Audio: www.netropolitan.org ©2002

Sketches for Sanctuary Awaits

Betye Saar

Sketches for Sanctuary Awaits: 4 May 1996

Ballpoint pen on paper

19 June 1996 (facsimile)

Ballpoint pen on sketchbook page

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Dolls sketchbook

In this early sketchbook, Saar recorded a range of dolls, from those that give comfort to those—like the two “pickaninny” dolls holding watermelon wedges—that cause pain. In the nineteenth century, manufacturers advertised such dolls, which were made of durable materials, as suitable for rough treatment, presumably by the white children for whom they were purchased. In Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court case that outlawed segregation in public schools in 1954, social scientists Kenneth and Mamie Clark submitted evidence from tests performed with dolls that demonstrated segregation’s demeaning impact on Black children. The perpetuation of stereotypical images reinforced those negative feelings.

Betye Saar

Dolls sketchbook, ca. 1968–70

Marker and watercolor in accordion-folded sketchbook

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Spread from Black Dolls sketchbook

Saar made these drawings while visiting an exhibition of handmade Black dolls. Produced between 1850 and 1940, the dolls were likely created by African Americans for children they knew. Until recently, positive, nonstereotyped Black dolls were rarely produced by commercial manufacturers.

Betye Saar

Spread from Black Dolls sketchbook, San Diego, Mingei International Museum, 24 May 2015

Photocopy, ink, watercolor, marker, and paper

collage on board

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Blend

Betye Saar

Blend, 2002

Collage of dress, gloves, fabric, fan, printed papers, and paint on paper

Collection of Neil Lane. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

Robert Wedemeyer

Rachel Federman: Saar's family plays an important role in her art. Her great-aunt Hattie, seen in the photo at the center of Blend, passed away in 1974, prompting Saar to make assemblages from her belongings. This is Betye Saar speaking about ancestry in the 1977 film, Spirit Catcher, the art of Betye Saar.

Betye Saar: The burdens that my mother had, my aunt had, my grandmother, my great-grandmother, all the way back to people that I don't even know, things that happened in their lifetime that they pass on to their children, but all of those things that become part of us that we transmit to our children. And as my daughters became women, I could see my hang-ups, my mother's hang-ups, my grandmother's hang-ups, and I said, "Wait a minute. I can do something about that. Because if I change and I'm their model, then they change too." It's like at one point, taking the responsibility of your life. There is the hope of being able to control my destiny, to move it from previous points where it was, where I was locked into that getting rid of all that programming and to becoming a true, free creative person.

Audio: © Suzanne Bauman

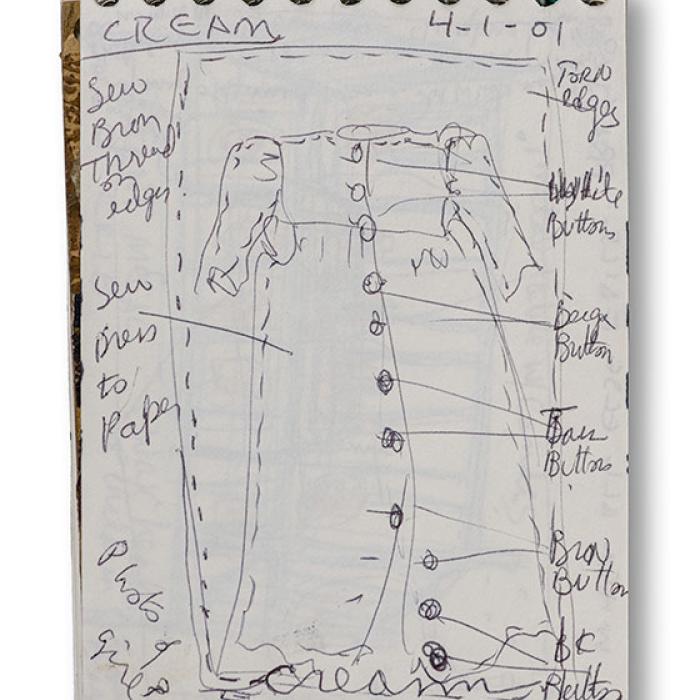

Cream

Cream is a “family portrait” featuring a child’s dress surrounded by photographs of Saar’s relatives. The young girl in the photo at bottom is Saar’s mother and the adults flanking the dress sleeves are Saar’s maternal grandparents. The generational story continues with Saar’s own handprint at bottom center and those of her youngest granddaughter, made when she was a year old. The butterflies that float among them suggest that while appearance is mutable, the essence of a creature remains the same.

Betye Saar

Cream, 2001

Collage of dress, buttons, photos, printed papers, lock of hair, metal ornament, handprints, and paint on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

Photo courtesy Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale, AZ, by Tim Lanterman.

Sketchbook pages for Blend and Cream

The sketch for Blend, a collage incorporating a vintage dress, is labeled “Blend (-Slipping-Passing),” suggesting that the pale figure wearing the dress in the final work is a Black woman passing as white. She holds in her gloved hands a framed photo of Saar’s late great-aunt Hattie, who has

The sketch for Blend, a collage incorporating a vintage dress, is labeled “Blend (-Slipping-Passing),” suggesting that the pale figure wearing the dress in the final work is a Black woman passing as white. She holds in her gloved hands a framed photo of Saar’s late great-aunt Hattie, who has

been something of a muse for the artist. The elegiac tone of Blend reflects the experience of racial passing as one of loss or exile. The sketch for Cream indicates Saar knew early in the creative process that she would use a particular dress and a variety of buttons in the final collage. The buttons progress from white at the top to black at the bottom, reflecting different shades of skin color. Saar’s grandfather was Native American and Black, while her grandmother was Irish.

Betye Saar

Sketchbook pages for Blend and Cream, 1 April 2001

Marker on paper; ballpoint pen on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

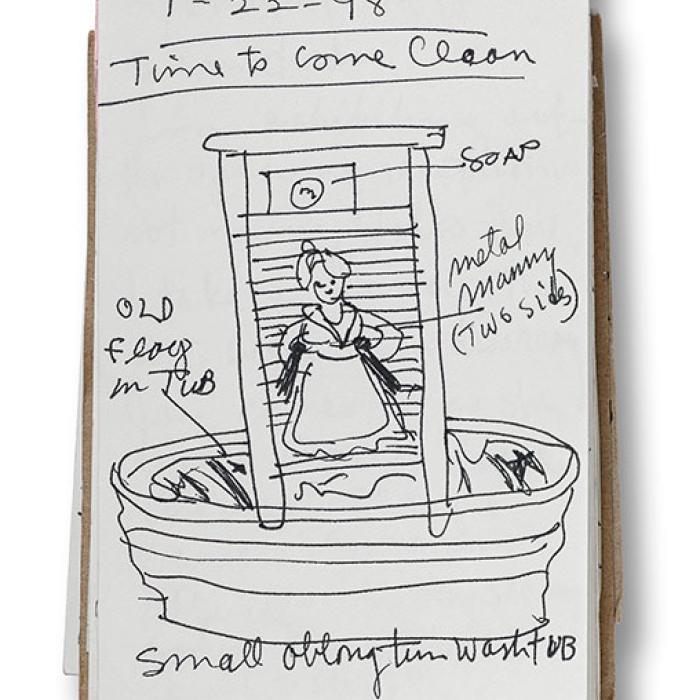

Maid-Rite—I’se in Town Honey

Saar began collecting washboards in the mid-1990s, inspired by memories of the one her grandmother used on her back porch. The artist has said she is interested in the “dichotomy between an object that was used to keep something clean and the person [using it], who was a slave and considered a dirty person because of the color of her skin.”

The work’s title references Aunt Jemima and her famous pancake mix, which in the 1910s and ’20s featured the advertising tagline “I’se in town, honey.” The figure of Aunt Jemima, which is based on the stereotype of a mammy, has appeared frequently in Saar’s work—inaugurated in her iconic The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972). In response to the recent news that the Aunt Jemima brand and image will finally be retired, Saar has said, “I transformed the derogatory image of Aunt Jemima into a female warrior figure, fighting for Black liberation and women’s rights. Fifty years later she has finally been liberated herself. And yet, more work still needs to be done.”

Betye Saar

Maid-Rite—I’se in Town Honey, 1997

Washboard with paint, stenciled lettering,

artificial eyes, and painted heads

Greenville County Museum of Art. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.© Betye Saar.

Brian Forrest

Sketchbook page for Maid-Rite— I’se in Town Honey

Saar’s sketches are a repository of sources and ideas for her completed works. Here, she wrote, “A.J. [Aunt Jemima] white invention.” She also attributed the words inscribed on the bottom of the washboard

to Henry Dumas (1934–1968), an African

American writer and activist who was

killed at age thirty-three by a New York

City transit police officer.

Betye Saar

Sketchbook page for Maid-Rite—

I’se in Town Honey,

17 July 1997 (facsimile)

Ballpoint pen on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Supreme Quality

In Supreme Quality, Saar shows Aunt Jemima as a gun-toting figure. At the same time, she is surrounded by accoutrements of feminine labor. A clock whose hands have been replaced by an American flag can be found on the back of the work, suggesting the unending nature of the mammy’s tasks. The inscription, “Extreme Times Call for Extreme Heroines,” which appears on a number of Saar’s assemblages, may refer to a controversial essay published in 1997 in The International Review of African American Art. Titled “Extreme Times Call for Extreme Heroes,” the text, in which Saar is quoted, addresses the incorporation of racist imagery into works by contemporary Black artists.

Betye Saar

Supreme Quality, 1998

Washboard with stenciled lettering, soap bar with

printed paper label, metal figurine with toy guns,

tin washtub, fabric, clock, and wood stand

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. © Betye Saar.

Photo courtesy Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale, AZ, by Tim Lanterman.

Sketchbook page for Supreme Quality

Betye Saar

Sketchbook page for Supreme Quality, 22 January 1998 (facsimile)

Marker on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

A Call to Arms

Lettered on the corrugated surface of this vintage washboard are lines from the poem “Proem” (1922) by Langston Hughes. The names of two American cities appear above: Chicago, the site of a bloody race riot in 1919; and Memphis, where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968. A crumb brush affixed to a mammy figurine with a noose around her neck stands before a photo of a lynching. Her outstretched arms are bullets and she is flanked by Black Power fists. For decades, Saar has transformed such derogatory images into potent symbols. She has said, “When Martin Luther King was assassinated, I reacted by creating a woman who’s my warrior: Aunt Jemima.”

Saar borrowed both the Hughes excerpt and the photo from a page in The Black Book, on view at right. She regards this influential volume as a sourcebook.

Betye Saar

A Call to Arms, 1997

Washboard with stenciled lettering, toy guns, compass, clock, wood picture frame, printed photo, crumb brush, twine, bullets, wood and metal spools, and Black Power fists

Collection of David Packard and M. Bernadette Castor. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.© Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Sketchbook page for A Call to Arms

Betye Saar

Sketchbook page for A Call to Arms, 1997

Ballpoint pen on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

The Black Book

The Black Book is an anthology of photographs, newspaper clippings, quotations, sheet music, patent applications, advertisements, and other ephemera, which together form a picture of Black life in America. The volume, assembled by Middleton A. Harris under the editorial eye of Toni Morrison—whose uncredited poem appears on the back jacket—is unflinching in its documentation of slavery, racially motivated violence, and the perpetuation of negative stereotypes. Saar was in the midst of her own reclamation of racist imagery when the book was published, having produced The Liberation of Aunt Jemima two years earlier. In A Call to Arms, Saar stenciled the Langston Hughes excerpt seen here onto a vintage washboard, where it joins other imagery to create a narrative of Black liberation.

Betye Saar

Middleton A. Harris (1908–1977)

The Black Book

First edition

New York: Random House, 1974

Rachel Federman: In the 1960s and '70s, Toni Morrison was an influential editor of African diasporic literature at Random House. Among her projects were books by Angela Davis, Henry Dumas, and The Black Book. This is Morrison speaking to author Junot Díaz about that time in her life.

Toni Morrison: Nevertheless, the job at Random was extremely important to me because there was a lot going on. As you remember, the late '60s and '70s, even the '80s, I wasn't able to participate politically, that is running up and down the streets in parades and with a megaphone, but I thought it would be a shame if that information was not in a book, the history of it. So I made it my business to collect African Americans who were vocal, either politically or just writing wonderful fiction.

Audio: New York Public Library

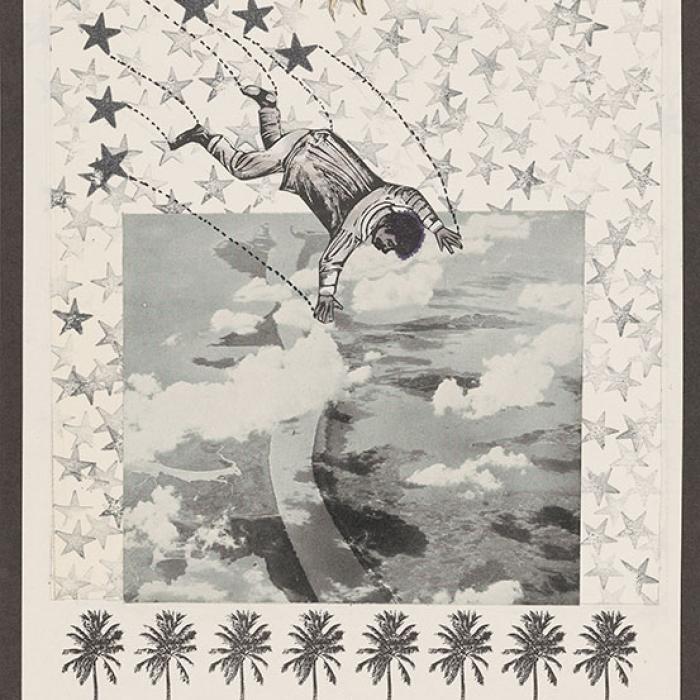

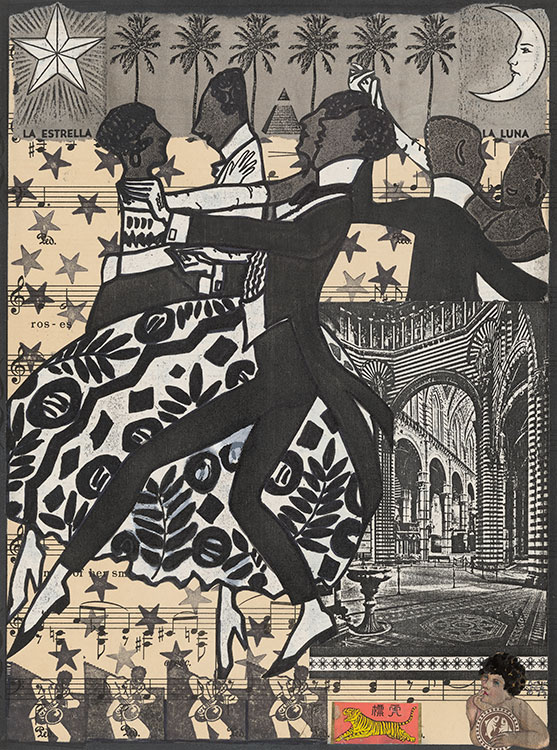

A Secretary to the Spirits

In 1975, the author and activist Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) invited Saar to create a series of collages for his book of poetry A Secretary to the Spirits. In another form of “call and response,” each of Saar’s collages is inspired by and named after one of Reed’s poems. Saar employed a layered approach that echoes Reed’s poetry, which combines references to the ancient and the contemporary, the spiritual and the mundane.

In the title piece of the series, a robed Black man who resembles a saint from a medieval gospel book holds a slice of watermelon in his hand. Beneath him we find the repeating image of a character—based on an offensive caricature—who has appeared in some form on packaging for Cream of Wheat since the 1890s. “Slavery is illegal, yet African Americans are still shackled by derogatory images,” Saar has written. Colorful borders of red patterned fabric catch the light like gold leaf in an illuminated manuscript. In all of the collages, Saar, who trained as a designer, made deft use of found patterns, such as decorative endpapers and perforated borders in The Return of Julian the Apostate to Rome, and musical staves in Tea Dancer Turns Thirty-Nine and Memo to Stevie Wonder. She also created repetition with found and custom-made rubber stamps in the shapes of stars, palm trees, and a Black saxophone player taken from the design of the cigarette paper brand Blanco y Negro.

All collages are from the collection of the Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee, 2017

A Secretary to the Spirits

Betye Saar

A Secretary to the Spirits, 1975–78

Collage of cut printed papers and fabric, with matte

and metallic paint and ink stamps, on laminated

paperboard

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee, 2017, 2017.306:1 . © Betye Saar.

Photography by Janny Chiu, 2018.

Pocadonia

Betye Saar

Pocadonia, 1975–78

Collage of cut and torn printed papers and Letraset border tape, with porous point pen, ink wash, watercolor, and ink stamps, on laminated paperboard

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee, 2017, 2017.306:2r. © Betye Saar.

Photography by Janny Chiu, 2020.

Sky Diving

Betye Saar

Sky Diving, 1975–78

Collage of cut printed papers, with porous point pen, watercolor, and ink stamps, on laminated paperboard

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee, 2017, 2017.306:4r. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.© Betye Saar.

Photography by Janny Chiu, 2020.

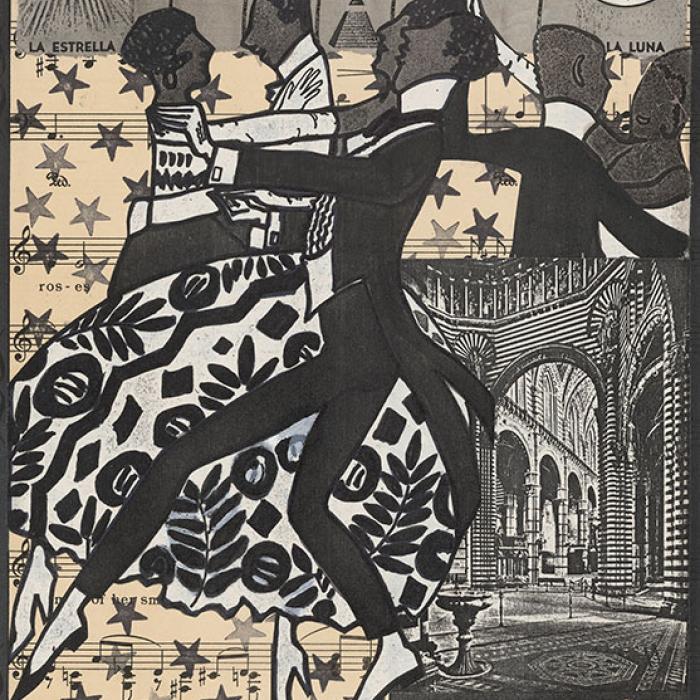

Tea Dancer Turns Thirty-Nine

Betye Saar

Tea Dancer Turns Thirty-Nine, 1977–78

Collage of cut and torn printed papers, with porous point pen, watercolor, acrylic paint, and ink stamps, on laminated paperboard

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee, 2017, 2017.306:6r. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.© Betye Saar.

Photography by Janny Chiu, 2020.

Memo to Stevie Wonder

Betye Saar

Memo to Stevie Wonder, 1975–78

Collage of cut printed papers, with watercolor, ink stamps, and artist’s thumbprint in ink, on laminated paperboard

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee, 2017, 2017.306:7r. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.© Betye Saar.

Photography by Janny Chiu, 2020.

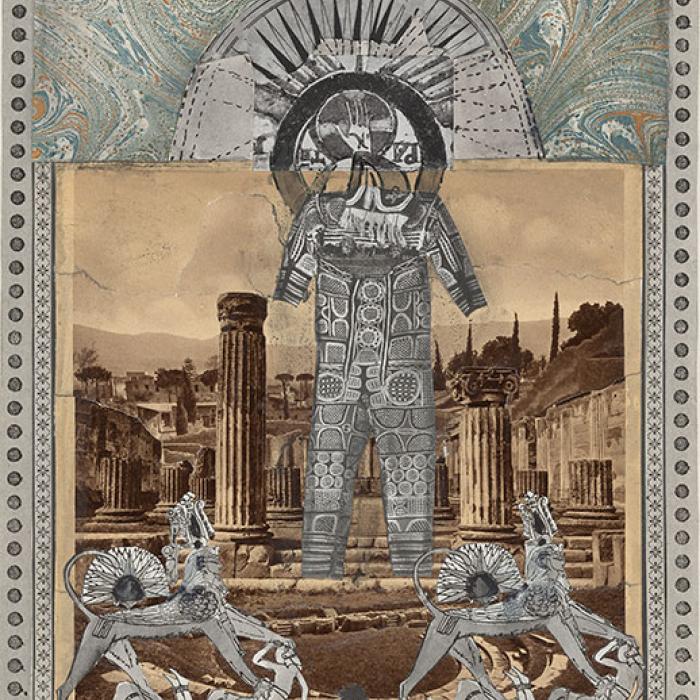

The Return of Julian the Apostate to Rome

Betye Saar

The Return of Julian the Apostate to Rome, 1975–78

Collage of cut and torn printed papers and fabric, with porous point pen, watercolor, and acrylic matte medium, on laminated paperboard

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee, 2017, 2017.306:3r. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.© Betye Saar.

Photography by Janny Chiu, 2020.

A Secretary to the Spirits

Betye Saar

Ishmael Reed (b. 1938)

A Secretary to the Spirits

Illustrated by Betye Saar

First edition

New York; London; Lagos: NOK Publishers, 1978

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee, 2017

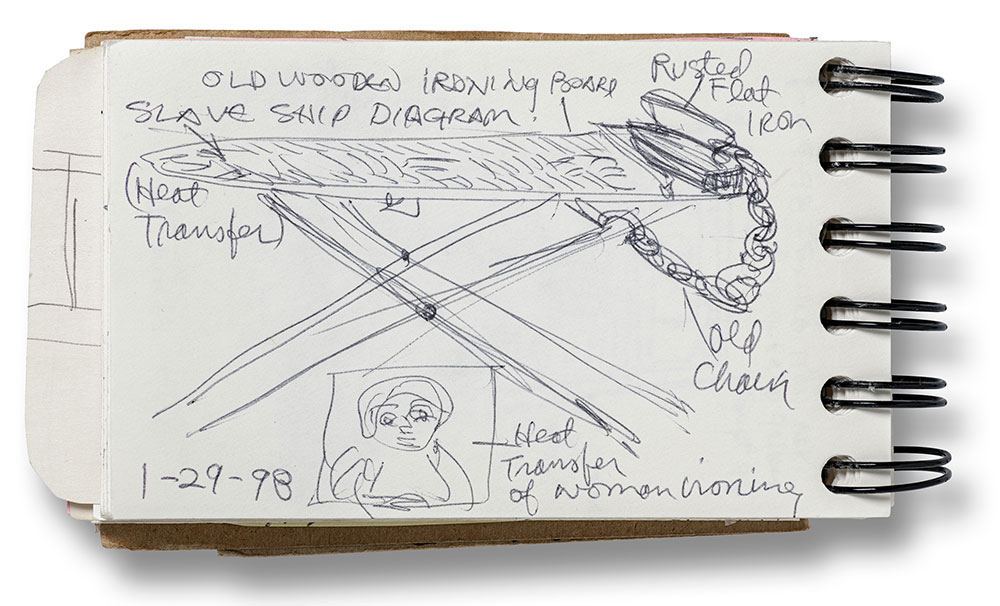

I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break

This tableau directly addresses issues of race and women’s work. The image on the ironing board—itself a traditional symbol of female labor—is borrowed from a well-known eighteenth-century print showing scores of Africans packed into a slave ship to cross the Atlantic. Saar’s construction also refers to the marking of enslaved people with branding irons, and to their enchainment in transit or as punishment. The “KKK” appliquéd to the sheet denotes the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan, still active today in the United States. According to Saar, this work communicates “the political message that you can treat me as a slave and I’ll bend down—I’ll bend down to pick cotton, I’ll bend to do this, to be a laborer—but I will not break.”

Betye Saar

I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break, 1998

Ironing board with printed images and text, flat iron, chain, bedsheet with appliqués, wood clothespins, and rope

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2018 Collectors Committee. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California.© Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Rachel Federman: This is Betye Saar speaking in 2019 about the creation of I'll Bend, But I Will Not Break.

Betye Saar: Well, I had been working on this series about labor, starting primarily with slave labor, which is like picking crops or cotton, and something, then sort of moved it on into labor in the household. And then when I was at one of my local sources where I find material, which is the Pasadena City College in Pasadena, California, one of the guys that I usually find neat things from had this old wooden ironing board. And the shape of the ironing board reminded me of the shape of a ship, meaning the slave ship, the diagram of the slave ship with all the slaves, how they're situated in it. I had used that before, and I found it in a book about slavery, but that's part of my visual language, just like a blackbird or a crow for Jim Crow or a hand, a palm of the hand for your fortune or something like that, and some of the other astrological signs. But when I saw that, I immediately got this idea. I said, "Oh, that slave ship diagram would look really good on it." And the shape of it was also a tomb in a way, like a casket. So it had this kind of sad, ominous feeling about it. It just seemed to make a statement about like you get off the slave ship and then you're a slave. And you wash and iron and clean, or pick cotton or whatever you have to do.

Audio: LACMA

Sketchbook pages for I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break

Betye Saar

Sketchbook pages for I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break

3 January (right) and 29 January (left) 1998

Ballpoint pen on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Still Ticking

Made shortly before Saar’s seventy-eighth birthday, this assemblage includes years and astrological glyphs on the inner left side that correlate to important dates in her life. The work’s title wittily refers to the timepieces in the sculpture—which, of course, are not ticking; indeed, they are either frozen in time or missing their hands. It also alludes to the artist herself, who is still making art well into her nineties.

Betye Saar

Still Ticking, 2005

Clocks, wood, paint, and white chalk

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

Brian Forrest

Rachel Federman: Saar uses old clocks, some with hands, some without in many of her sculptures. Her studio was filled with clocks waiting to be incorporated into assemblages like this one. Here is Betye Saar speaking at the Hammer Museum in 2014 about time.

Betye Saar: The game of time is played week by week, hour by hour, day by day. The sands of time are always shifting, drifting as years become decades, and time sends us on the journey to elsewhere to the dark side of the moon.

Audio: The Hammer Museum

Sketchbook page for Still Ticking

Betye Saar

Sketchbook page for Still Ticking, 23 March 2004

Marker on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Travel Sketchbooks

Throughout her life, Saar has made drawings and collages in response to the places she visits. Unlike the other sketchbooks on display, these works were created without a specific assemblage, collage, or sculptural tableau in mind. Instead, they resemble private souvenirs, combining material and visual traces of her travels with elements

of her established artistic vocabulary. For example, Saar’s 1975 Mexico sketchbook includes images of eyes, hearts, hands, and celestial bodies—leitmotifs that appear throughout her work. Among the mementos pasted into her 1994 sketchbook from Brazil is an image of a lion; as a Leo, Saar frequently includes lions in her art.

All travel sketchbooks are from the collection of Betye Saar, courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles

Rachel Federman: As you look at Betty Saar's travel sketchbooks, listen to her reciting her 1993 poem, My Secret Heart.

Betye Saar: My secret heart is seduced by twilight. It remembers the colors of dreams. It longs for solitude and the exotic. My secret heart is a wanderer. It sails the sea of imagination. It soars beyond the clouds, seeking the mysterious. It moves through time, dream time, and space, mind space. My secret heart seeks the dusty, musty, forgotten corners. It constantly haunts hunts, collects, gathers objects, images, feelings. It mixes, matches, embellishes, simplifies, camouflages, fabricates to empower the ordinary to invent artifacts. My secret heart, bridges, memory and vision. It pays homage to lost rituals of unknown civilizations. It expands horizons only to condense them into a frame, a box, a room. My secret heart is ageless. It beats within the rainbow babe in the woods, and it dwells in the house of whispers.

Audio: www.netropolitan.org ©2002

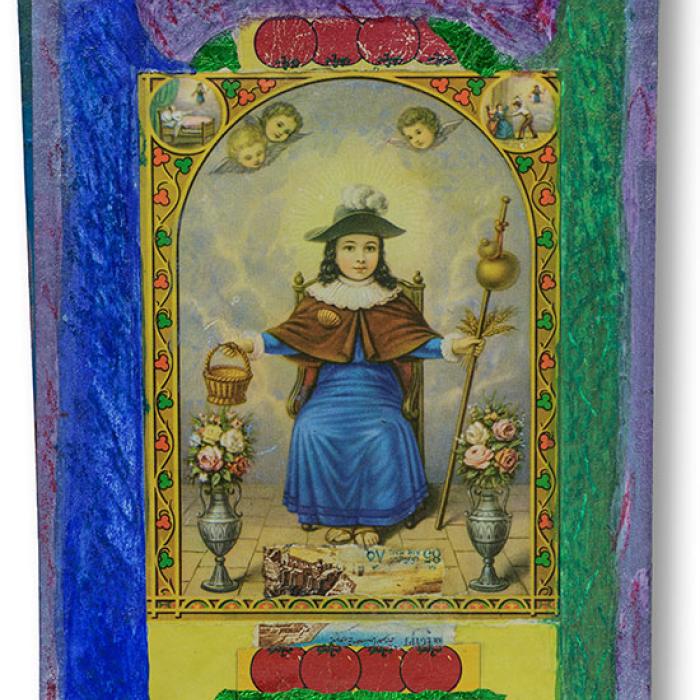

Page from U.S.A. sketchbook, Santa Fe, Museum of International Folk Art, 1988–91

Betye Saar

Page from U.S.A. sketchbook, Santa Fe, Museum of International Folk Art, 1988–91

Watercolor and ballpoint pen on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Page from California sketchbook

Betye Saar

Page from California sketchbook, 1975

Acrylic and collage on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Page from Brazil/Los Angeles sketchbook

Betye Saar

Page from Brazil/Los Angeles sketchbook, 1983/88

Collage and gouache on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Page from Oaxaca sketchbook

Betye Saar

Page from Oaxaca sketchbook, April 1985

Acrylic, gouache, and collage on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Spread from Mexico sketchbook

Betye Saar

Spread from Mexico sketchbook, June 1975

Gouache, watercolor, and pencil on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

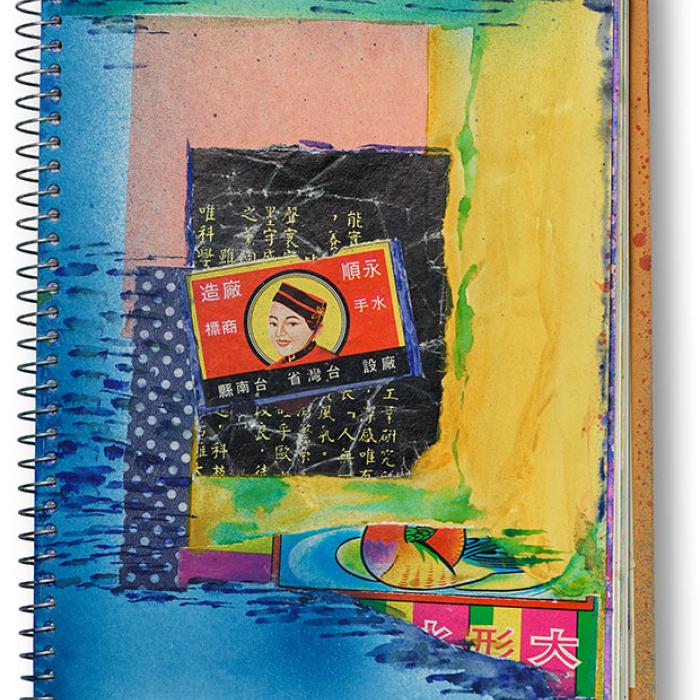

Spread from Taiwan sketchbook

Betye Saar

Spread from Taiwan sketchbook, 1988

Watercolor and collage on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Spread from Haiti sketchbook

Betye Saar

Spread from Haiti sketchbook, 26 July 1978

Watercolor, marker, and colored pencil on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Page from Haiti sketchbook

This sketchbook page incorporates black-and-white lozenge motifs from a grave monument Saar saw in a cemetery in Jacmel, Haiti. They are combined with imagery seen throughout her work: celestial bodies, a heart, and a burning cross.

Betye Saar

Page from Haiti sketchbook, 24 July 1974

Watercolor, ballpoint pen, and ink on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

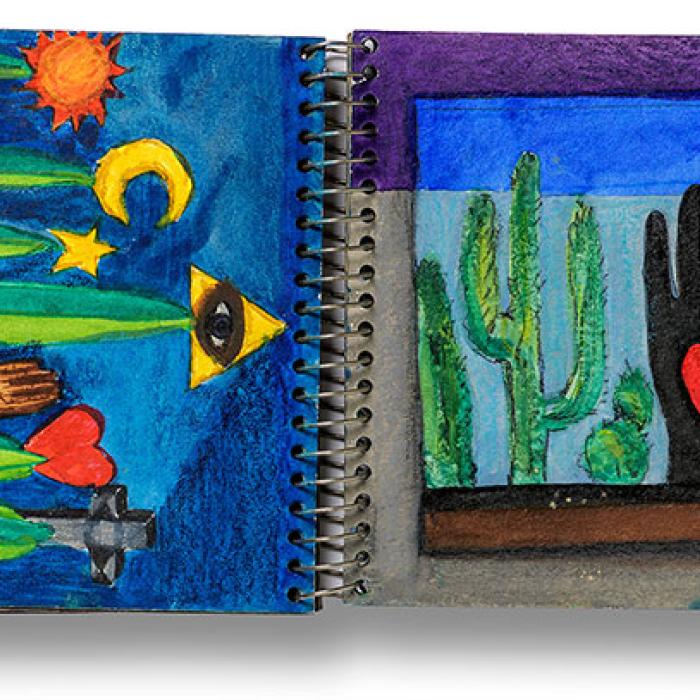

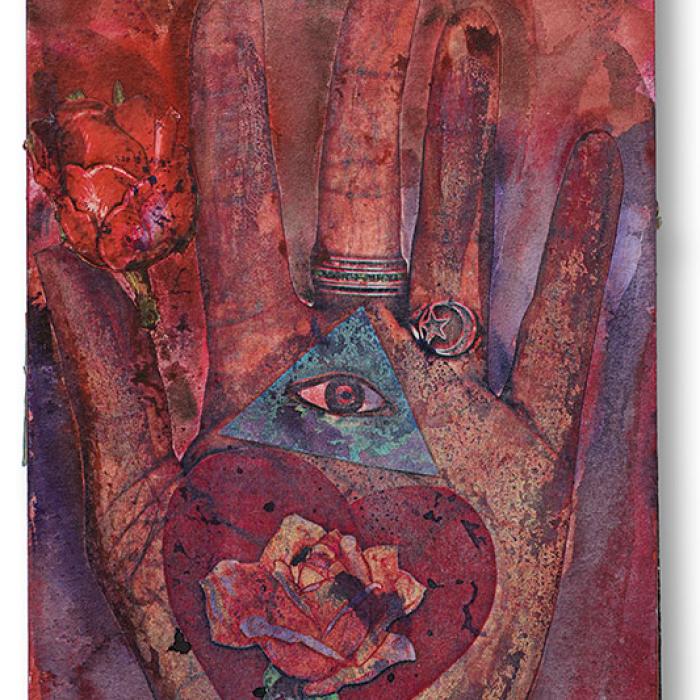

Page from Aix-en-Provence, France/Los Angeles sketchbook

This sketchbook page refers to the hamsa, an amulet in the form of the palm of a hand that is popular throughout the Middle East and North Africa. Often containing the image of an eye, the hamsa is considered a

defense against the evil eye. The palm of the hand—here a silhouette of the artist’s own—symbolizes fortune for Saar.

Betye Saar

Page from Aix-en-Provence, France/Los Angeles sketchbook, 8 September 2004

Collage and watercolor on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Page from Brazil sketchbook

In the fall of 1994, Saar traveled to Brazil for the twenty-second International Biennial in São Paulo. Her work was featured

in an exhibition alongside that of John Outterbridge (b. 1933), a fellow assemblage artist from California. The following year, Saar visited South Africa when the exhibition traveled to Johannesburg.

Betye Saar

Page from Brazil sketchbook, 1994

Watercolor and collage on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

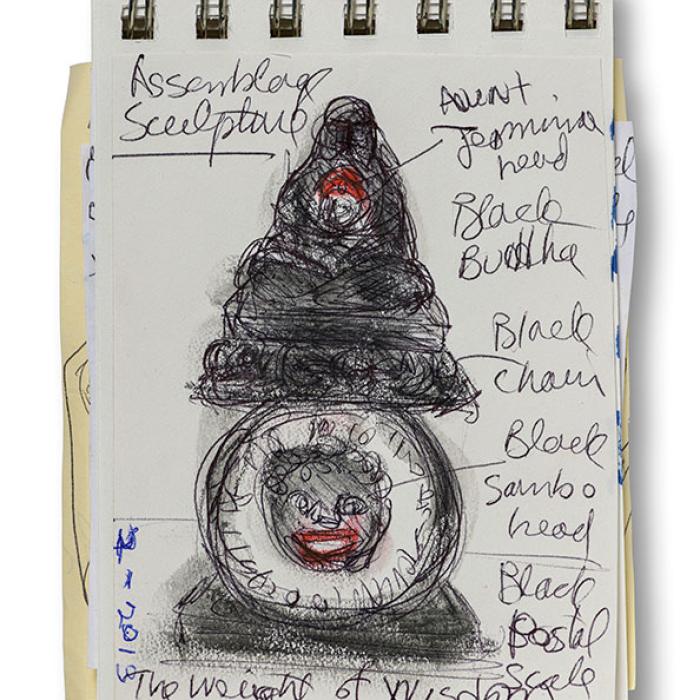

The Weight of Buddha (Contemplating Mother Wit and Street Smarts)

In The Weight of Buddha, Saar retains her focus on race while

simultaneously returning to her early interest in spirituality. The

assemblage is an amalgam of Buddha, Aunt Jemima, Black Sambo—

a children’s book character drawn as a racist “pickaninny” caricature—

and a postal scale, which for Saar symbolizes justice. The

meditative, esoteric figure of Buddha, who is literally being weighed

on the scale, contrasts with the commonsense values ascribed to

Aunt Jemima (Mother Wit) and Black Sambo (Street Smarts).

Betye Saar

The Weight of Buddha (Contemplating Mother Wit and Street Smarts), 2014

Painted figures, chain, and postal scale

The Eileen Harris Norton Collection. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

Robert Wedemeyer

Sketchbook page for The Weight of Buddha (Contemplating Mother Wit and Street Smarts)

Betye Saar

Sketchbook page for The Weight of Buddha (Contemplating Mother Wit and Street Smarts), February 2013

Ballpoint pen, colored pencil, and wash on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

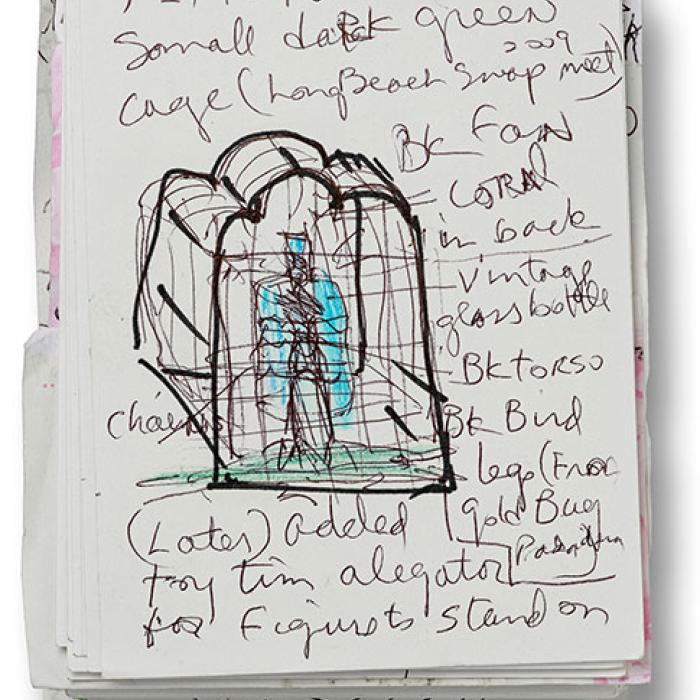

The Edge of Ethics

In 2006, Saar began collecting cages like this one, which she purchased at a swap meet in Long Beach, California. She has said, “The cage, an object of containment, for me became a metaphor for many concepts: ideas of limitations, of emotions, of racism, of feminism, of death, of beauty, of mystery, of legends and superstition.”

Betye Saar

The Edge of Ethics, 2010

Metal cage, figures, chain, glass bottle,

and fan coral

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Sketchbook page for The Edge of Ethics

Betye Saar

Sketchbook page for The Edge of Ethics, 14 January 2010 (facsimile)

Ballpoint pen, marker, and colored pencil on paper

pasted into sketchbook

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

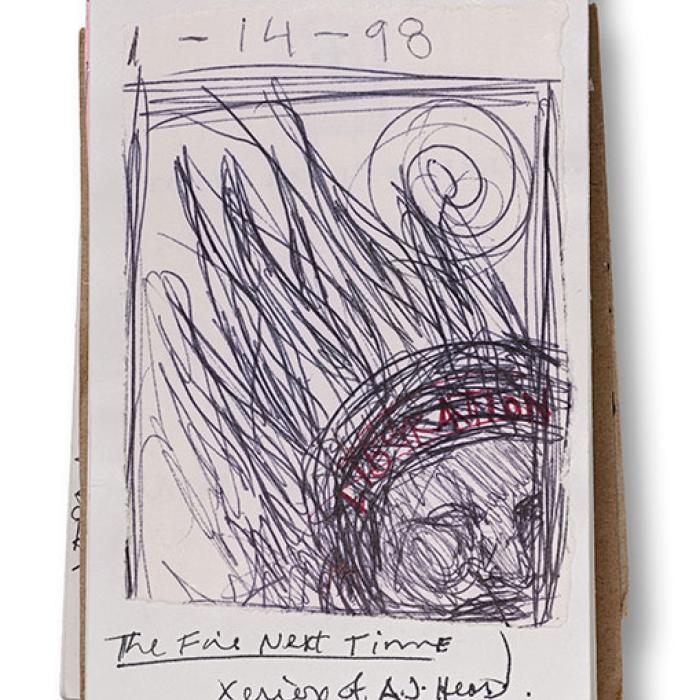

Blow Top Blues: The Fire Next Time

Aunt Jemima’s fixed stare and rigid grin in this work refer to the song “Blow Top Blues” by jazz musician Leonard Feather (1914–1994). Popularized in the 1940s, it tells the story of a woman who is going mad. Saar’s subtitle, The Fire Next Time, is taken from James Baldwin’s 1963 book of that title, which addresses the role of race in American history and the connections between race and religion. Baldwin in turn took his title from the antebellum Negro spiritual “Mary Don’t You Weep.”

Betye Saar

Blow Top Blues: The Fire Next Time, 1998

Lithograph and hand-painted collage on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

Photo courtesy Museum De Domijnen, Sittard, Netherlands, by Bert Janssen.

Sketchbook page for Blow Top Blues: The Fire Next Time

Betye Saar

Sketchbook page for Blow Top Blues: The Fire Next Time, 14 January 1998 (facsimile)

Ballpoint pen and collage on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

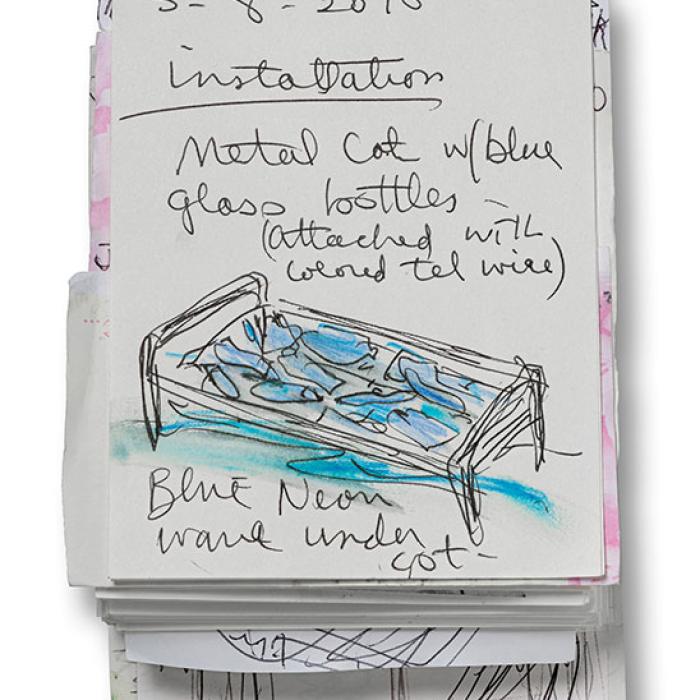

Woke Up This Morning, the Blues was in My Bed

The title of this tableau references “Empty Bed Blues,” a song recorded by Bessie Smith in 1928. The cot can be seen as a spirit bottle bed, akin to the traditional bottle tree used by the Kongo civilization in west-central Africa to ward off evil spirits. Saar used the cot, which she bought at a secondhand store on Western Avenue in Los Angeles, in at least two earlier installations (in 1990 and 1994); she loves not only using recycled objects but also recycling them herself. In a February 2001 sketch—the first of four she made for this work—Saar introduced the idea that the cot would sit on a bed of coal, a material that evokes energy and change.

Betye Saar

Woke Up This Morning, the Blues was in My Bed, 2019

Metal cot, glass bottles, neon, and coal

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

Robert Wedemeyer

Rachel Federman:

First conceived in 2001 and realized for this exhibition, Woke Up This Morning, the Blues was in My Bed was inspired in part by an old blues sons that Saar referenced in a sketch of August 24th 2001 on view nearby. This is a clip from the song Empty Bed Blues, performed by blues legend Bessie Smith in 1928.

MUSIC:

I woke up this morning with a awful aching head.

I woke up this morning with a awful aching head.

My new man had left me, just a room and a empty bed.

Bought me a coffee grinder, that's the best one I could find.

Bought me a coffee grinder, that's the best one I could find.

Oh, he could grind my coffee, 'cause he had a brand-new grind.

Sketchbook pages for Woke Up This Morning, the Blues was in My Bed

Betye Saar

Sketchbook pages for Woke Up This Morning, the Blues was in My Bed:

24 February 2001 (facsimile)

Ballpoint pen and colored pencil on paper

14 August 2001 (facsimile)

Ballpoint pen and colored pencil on paper

8 March 2010

Marker, colored pencil, and wash on paper

22 May 2013 (facsimile)

Ballpoint pen on paper pasted into sketchbook

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. © Betye Saar.

photo © Museum Associates/LACMA