Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

What is a novel made of? Stories, characters, sentences, ideas: certainly. But don’t forget ink and paper. And where would a self-portraitist be without a mirror? On their way to communion with the muses, artists stop off at the supply store. Let’s follow along.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

What looks at first glance like a bespoke Zippo lighter is Charles Dickens’s portable ink pot. It was given to the young author in 1833 by his friend, and later biographer, John Forster. Though Dickens lived and wrote well into the age of commercially produced metal pens, he chose to write with goose quills. Equipped with prepared quills and this pocket-sized ink pot, he could, and did, write almost anywhere.

Ink pot owned by Charles Dickens (1812–1870), ca. 1833. Metal in wooden frame, 5.5 x 4.5 cm. MA 6061. Gift of Chauncey D. Stillman, 1971.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

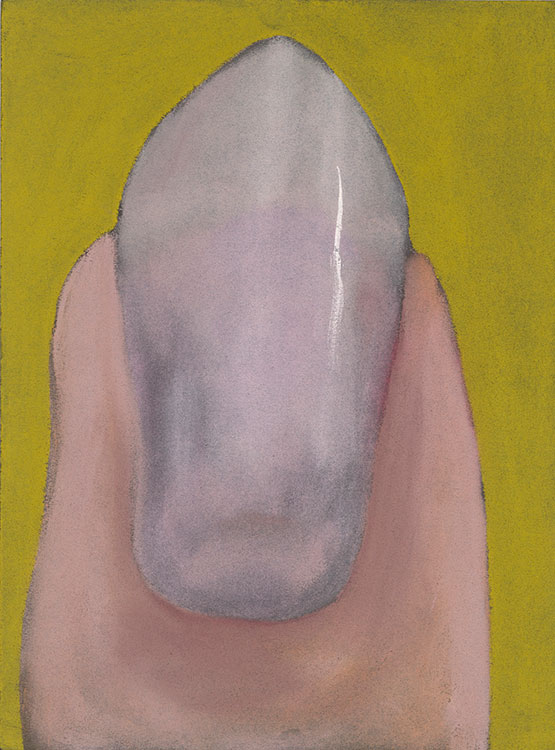

In place of the traditional tools for blending pastels on the sheet—a stump or a tapered cylinder of rolled paper called a torchon—Lucas Samaras used his finger. Samaras said it served to help him remain aware of the physicality of his creative process; he has described this drawing as a self-portrait of sorts, portraying his finger as a drawing implement.

Lucas Samaras (1936– ), Untitled, July 3, 1965. Gift of Lucas Samaras and Arne Glimcher, The Morgan Library & Museum, 2013.59. © Lucas Samaras, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

Time spent in Rome was long considered essential to an artist’s education, and most traveling artists recorded their impressions of the Eternal City in sketchbooks. The Morgan holds a number of these, including examples by Edgar Degas and Joshua Reynolds and the one shown here, used by Hubert Robert when he was in Rome during the early 1760s.

Hubert Robert (1733–1808), Roman Sketchbook, ca. 1760–63. Purchased as the Gift of the Fellows with the special assistance of an anonymous contribution from a foundation, 1958.5.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

“‘Did it rain to-morrow?’ asked Monsieur Grenouille. ‘Yes it was!’ replied Monsieur Crapaud.” In the nineteenth century, humor entered the classroom as a means of teaching subjects as dry as auxiliary verbs. Percival Leigh, author of the exchange above, employed comedy to improve children's facility with English grammar, Latin, and arithmetic. This cover design for a "yellowback" reprint of his popular book is the work of another writer and artist whose preferred implement was caricature: Alfred Henry Forrester, a regular contributor to Punch magazine.

Alfred Crowquill (i.e. Alfred Henry Forrester, 1804–1872), cover design for The Comic English Grammar, ca. 1852. Pen and ink and watercolor over graphite. Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987, 1986.2213.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

Whatever subject is represented here (a trio of dancers? the Three Graces?), it plays a secondary role to the object itself: a roughly trimmed sheet of photographic printing paper. Ei-Q was trained in both western-style painting and photography. He coined the term photo-dessins (photo-sketches) for improvised prints such as this one, which he exposed in the darkroom, using a light pen, paper cutouts, and loose-mesh fabric. In place of the mechanical precision of the camera, he welcomed accidental effects of action, like those that characterize the mixed-media canvases of Surrealist painters such as Max Ernst and André Masson.

Ei-Q (Ei Kyū, born Sugita Hideo) (1911–1960), Untitled (Photo-Dessin), ca. 1950. Gelatin silver print, 11 5/8 x 9 5/8 inches, irregular. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, 2017.291. © 2020 Estate of Ei-Q

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

A Ragamala (garland of ragas) is a series of paintings in which different musical modes are personified by male and female figures (ragas and raginis). Here, Ragini Todi, seated on a rich carpet, turns her spinning wheel. As her abstracted gaze suggests, her thoughts are elsewhere. She is longing for her lover, her melancholy mood heightened by the gray background. In the Rajasthani tradition, Ragini Todi is shown wandering alone in a forest, playing a musical instrument and attracting deer drawn to her beauty and song. In paintings such as this one, however, from the far north of India, a spinning wheel helps to occupy her time. Its constant motion is her only distraction from thoughts of her absent lover.

Todi Ragini, from a Ragamala series, Himachal Pradesh, India, Bilaspur School, ca. 1725, MS M.1016. Gift of Paul F. Walter, 1979.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

The tools of medieval scribes and artists rarely survive. A spectacular exception is this wooden writing box, one of three found in a buried hoard that included some sixty manuscripts. Once belonging to the library of the monastery of Archangel Michael in the Fayyum region of Egypt, the objects were buried in a cistern in the tenth century, most likely by monks fleeing from danger. The hoard was discovered by chance in 1910, resulting in an international sensation. Like the beautifully illuminated manuscripts that they helped create, the writing boxes are precious works of art, with bronze fittings and intricate carving throughout. The lid of this box slides out, revealing compartments for storing reed pens, inks, and pigments.

Writing box, Egypt, al-Hamuli, ca. 9th century. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan in 1911. Coptic Writing Box 1.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

Claude Debussy’s composing notebook, still equipped with his pencil, offers a sense of intimacy with the composer and his creative process. This volume contains sketches for several of his works, including Images for orchestra, Ibéria, and Préludes for piano (Book I).

Claude Debussy (1862–1918), sketchbook, autograph manuscript, ca. 1908. Robert Owen Lehman Collection, on deposit.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

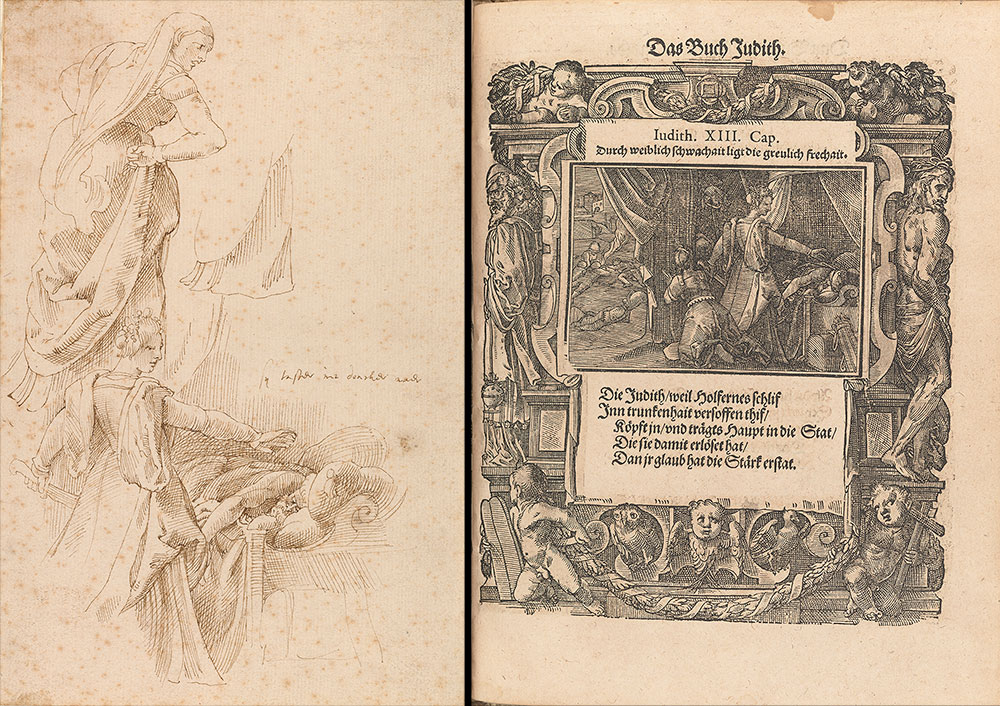

Aspiring artists derived a seemingly endless repertoire of visual motifs and compositional ideas from the 168 woodcuts of Old and New Testament scenes in Tobias Stimmer’s Neue künstliche Figuren Biblischer Historien (Basel, 1576)—the so-called Stimmer Bible. As a teenager, Peter Paul Rubens copied a number of illustrations from the book, including two featuring Old Testament women: Judith and the wife of Job. Visual motifs originating in the Stimmer Bible can be found in several of Rubens’s mature works. This suggests that these drawings stayed with Rubens over the course of his career.

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), Job's Wife and Judith and Holofernes, ca. 1595. Pen and brown ink on paper. Gift of Otto Manley, inv. 1984.46.

Tobias Stimmer (1539–1584), Neue künstliche Figuren Biblischer Historien, Zu Basel, Bei T. Gwarin, 1576. Gift of Otto Manley, 1984. PML 78265.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

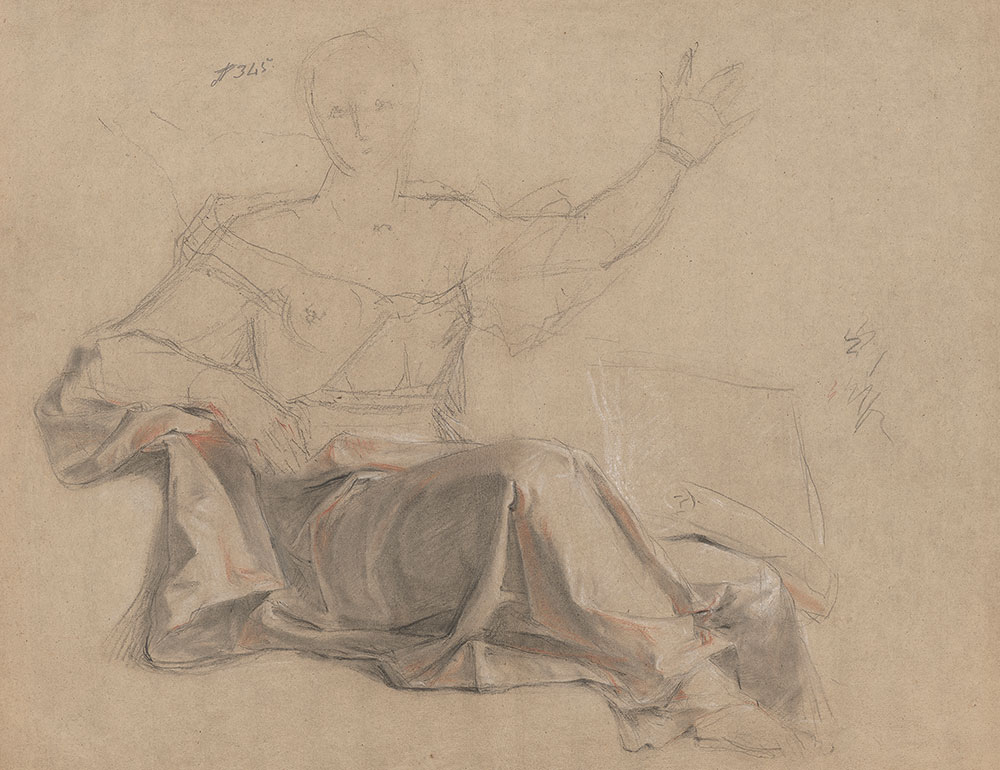

The featureless, schematic head, blocky shoulders, and cone-shaped fingers extending from a roughly articulated hand indicate that Louis Galloche prepared this drapery study using a poseable mannequin covered in a swath of fabric. Especially during the early phases of a project, mannequins and jointed models, known as lay figures, allowed artists to execute preparatory work without depending on human models.

Louis Galloche (French, 1670–1761), Drapery Study. Black, red, and white chalk on brown paper. Purchased on the Herzog Fund and as the gift of Margot Gordon and Marcello Aldega, 2001.7.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

According to medieval tradition, Saint Luke was at once an evangelist, a painter, and a doctor. In this miniature, Luke and his emblematic ox are seen with the tools of his three trades. As the author of one of the four Gospels, he is shown writing with a pen in a book; his inkwell and pen case rest on a table nearby. Propped behind them is the painting of the Virgin Mary he was thought to have painted from life. On the shelf above his head stand two round bottles of clear glass, of the type used by medieval doctors to examine urine specimens. To this day, many hospitals are named St. Luke’s.

Jean Fouquet, Saint Luke, from the “Hours of Jean Robertet,” France, Tours, ca. 1465–68, MS M.834, fol. 15. Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1950.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

Nabu, the god of writing, faces a worshiper from atop a dragon. His square-topped headdress is adorned with a single horn and surmounted by a star. In his right hand, he brandishes his emblem: the stylus or double wedge, essential for impressing cuneiform writing onto clay tablets. Standing on a lion-griffin behind Nabu, enveloped in a nimbus of stars and globes, is Ishtar, the major star goddess of the Assyrians. The carver used a drill on this hard, semi-precious stone to create the dramatic stars and astral symbols that lend divine magnificence to the deities.

Ancient cylinder seal with modern impression showing a worshiper standing before deities, Mesopotamian, Neo-Assyrian period, ca. 9th/ early 8th century B.C. Carnelian, H. 3.9 cm. (1.54 in.), Diam. 1.8 cm. (.71 in.). Acquired by Pierpont Morgan between 1885 and 1908. Morgan Seal 691.

Morganmobile: Tools of the Artist

Central to Hans Breder’s work and teaching was the principle of “Intermedia”: art conceived as a perpetual coming-together of idioms including sculpture, video, collage, installation, and performance. In a series of photographs he made in Iowa and Mexico in 1969–73, nude figures pose (or, as the title of this image puts it, dance) with the squares of highly polished reflective metal Breder employed in his sculptural practice.

Hans Breder (1935–2017), Chair Dance, 1969. Gelatin silver print, 8 x 8 inches (image). Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, 2018.61.

© Estate of Hans Breder