Morganmobile: Justice

Beginning in 1983, Danny Lyon sojourned several times in Haiti to document life under dictatorship, and in its aftermath. He made this photograph in a marketplace one month after Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier fled the country, ending twenty-nine years of family rule. The mental focus and physical intimacy of these praying young women form an image of collective inner strength: history’s antidote to chronic criminal misgovernment.

Danny Lyon (b. 1942), Haitian Women, March 1986. Gelatin silver print. Purchased as the gift of Ronald R. Kass. 2016.157.

© Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos

Morganmobile: Justice

In the sixth century BCE, the inventor Perillos created a life-sized bronze bull and presented it to the Sicilian tyrant Phalaris, proposing that condemned criminals could be roasted alive inside it. Phalaris, however, ordered that Perillos be the bull’s first victim: the moment shown here. In some versions of the tale, the cruel ruler himself later met the same fate. The drawing is preparatory for a fresco that once adorned a Roman façade.

Polidoro da Caravaggio (ca. 1499–ca. 1543), The Condemnation of Perillos, ca. 1520. Pen and brown ink and wash, with white opaque watercolor, over black chalk. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan in 1909. Inv. I, 20.

Morganmobile: Justice

These two allegorical illuminations of enthroned rulers appear in “mirrors for princes," a popular literary genre throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Textbooks for kings and other rulers flourished in the West as well as in Chinese, Islamic, and Byzantine cultures. At left, a monarch is advised by the four cardinal virtues. Fortitude, Temperance, and Prudence give the king his sword, shoes, and crown, but it is Justice who confers on him a scepter, the symbol of his right to rule. The ruler on the right is identified as Magnanimity (greatness of spirit). A figure labeled Law looks his way, brandishing a sword, but he turns to gaze at Justice, whose blindfold and bound hands symbolize impartiality.

Left: Advice to Kings, in French, France, Paris(?), 1347–50. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911. MS M.456, fol. 25v (det.).

Right: Pierre Gringore: The Abuses of the World, in French. France, Rouen, ca. 1510. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1899. MS M.42, fol. 33r (det.).

Morganmobile: Justice

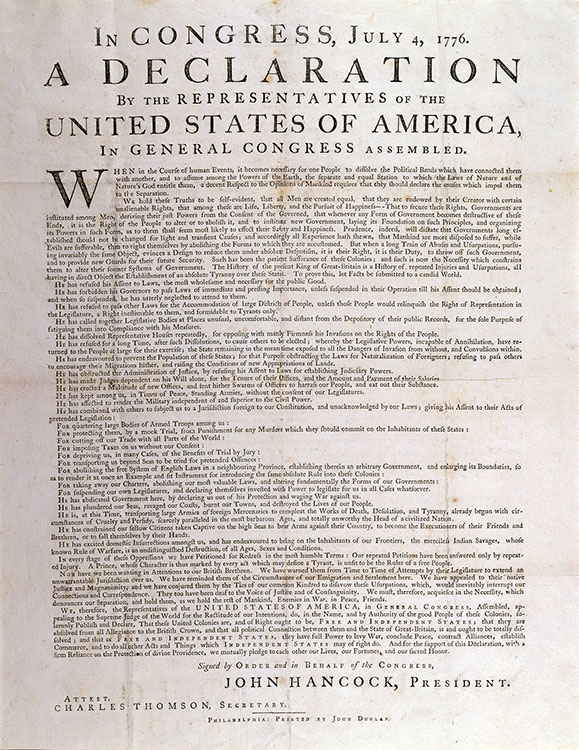

The first edition of the Declaration of Independence numbered perhaps one hundred or two hundred copies, printed on the evening of 4 July, 1776. Twenty-six copies are known to have survived. This one belonged to Benjamin Chew (1722–1810), Chief Justice of Pennsylvania. Sympathetic though he was to the American cause, Chew—a Quaker by birth and a committed pacifist—refused to support armed resistance against the king. When the British troops approached Philadelphia, he was arrested and exiled to New Jersey. Chew was rehabilitated after the revolution and spent his last years presiding at the Pennsylvania High Court of Errors and Appeals.

In Congress, July 4, 1776. A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America. Philadelphia: Printed by John Dunlap, 1776. Gift of the Robert Wood Johnson Jr. Charitable Trust, 1982. PML 77518.

Morganmobile: Justice

Standing on a dais and wearing a turban, Pontius Pilate, the prefect of the Roman province of Judaea, presents Christ—weary, disrobed, and bound—to the unruly crowd below (Matthew 27:15–26). An allegorical representation of Justice stands in the niche behind Pilate, but it is the mob who will condemn the prisoner to crucifixion. In this rare early impression, executed entirely in drypoint and printed on warm-hued Japanese paper, Rembrandt’s strokes have a rapid, sketch-like quality, enhancing the urgency and emotional drama of the scene.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606-1669), Christ Presented to the People: Oblong Plate, 1655. Drypoint on Japanese paper. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan in 1905. Inv. RvR 118

Morganmobile: Justice

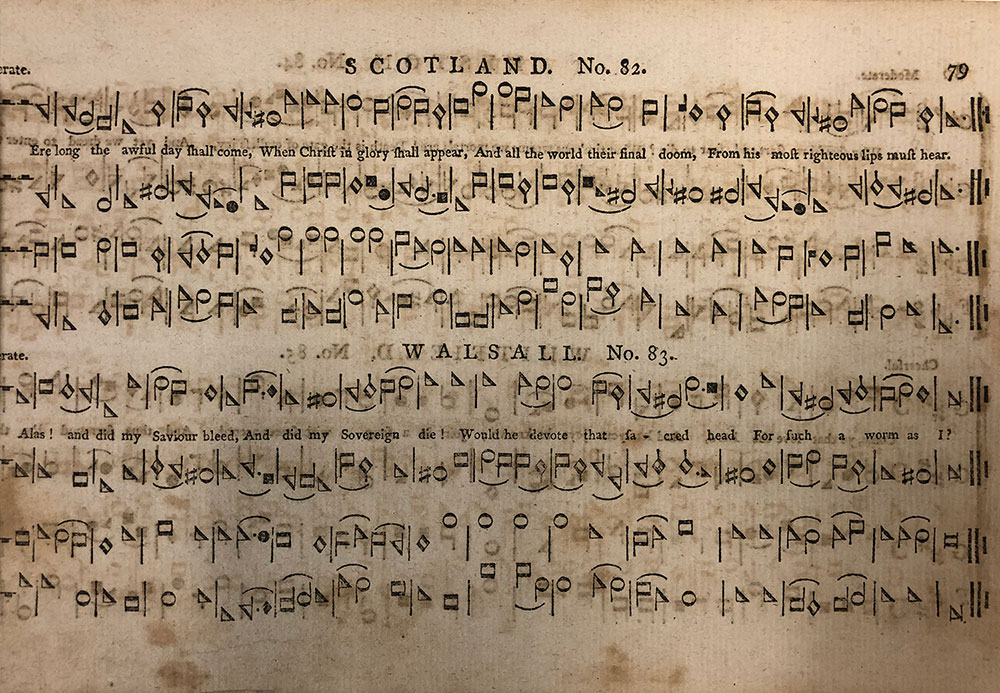

"Ere long the awful day shall come, When Christ in glory shall appear, And all the world their final doom, From his most righteous lips must hear." This early American songbook presents four-part harmony in shape-note notation without staves. As a learning and sight-reading aid, each note is rendered as a shape denoting its relative pitch.

Andrew Law (American, 1749–1821). "Scotland. No. 82" in The art of singing; in three parts, p.79, fourth edition, with additions and improvements. Cambridge: W. Hilliard, 1803. James Fuld Collection, 2008.

Morganmobile: Justice

King Ur-Namma is chiefly remembered today for creating the earliest known surviving legal code; a year of his era was called the “Year Ur-Namma made justice in the land.” In this sculpture, originally placed in a sealed foundation deposit under the gate of the temple of Enlil, he performs the lowliest of tasks, carrying a basket of mud to make the first bricks for the restoration of the temple. This act of deep piety stresses the king’s humility and deference to the divine. The figure was made not for display during Ur-Namma’s lifetime but for the eyes of the gods, and of mortals in a hoped-for future.

Foundation Figure of King Ur-Namma Inscribed in Sumerian: Ur-Namma, king of Ur, king of Sumer and Akkad, the one who built the temple of Enlil. Mesopotamia, Third Dynasty of Ur (ca. 2112–2004 B.C.). Copper. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907. MLC no. 2628.

Morganmobile: Justice

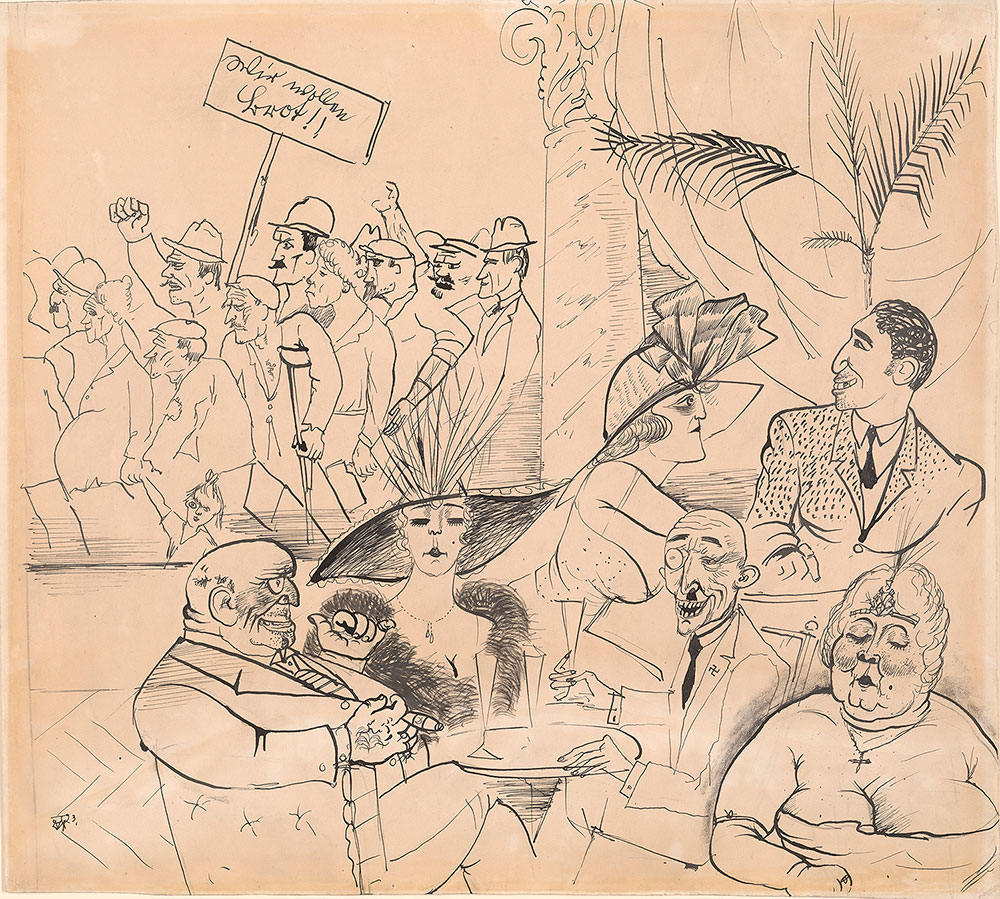

Otto Dix’s satirical drawing decries the widening economic disparity dividing the social classes in Weimar Germany. In the highly detailed foreground, an array of extravagantly attired bourgeois drink champagne in a sumptuous setting. Dix adopts a more summary and straightforward approach to representing the proletarians in the background, whose slogan, “Wir wollen Brot!” (“We want bread!”), gives the drawing its name.

Otto Dix (German 1891−1969), We Want Bread! (Wir wollen Brot!), 1923. India ink over traces of graphite pencil on wove paper, 15 1/4 x 16 3/4 inches (38.7 x 42.6 cm). Bequest of Fred Ebb, 2005.125.

© Otto Dix/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Morganmobile: Justice

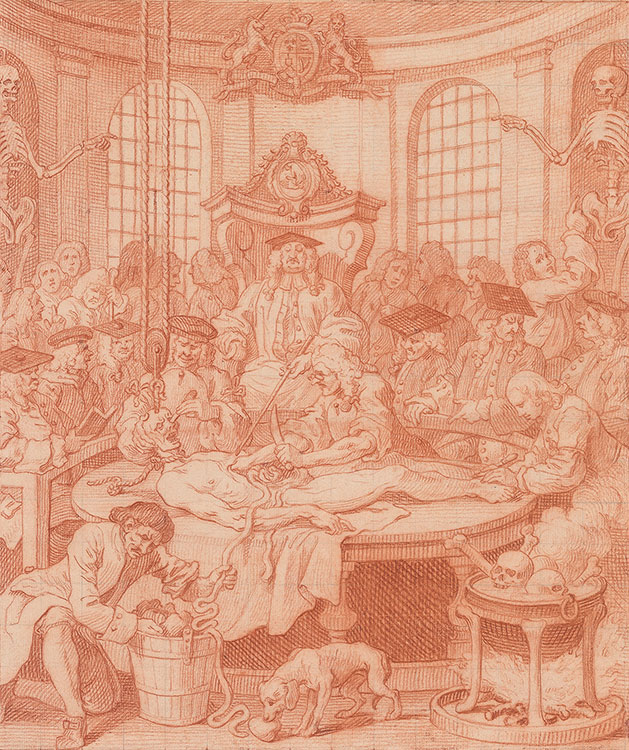

Shocked by the casual cruelty he saw in the streets of London, William Hogarth produced a series of prints illustrating the life story of sadistic Tom Nero. Tom tortures small animals, then larger ones, and finally murders his pregnant lover. Sent to the gallows, he is denied burial. His body is brought to a medical theater, where it is disemboweled by surgeons and turned into an anatomical model. Dissection of the hanged was a controversial topic when Hogarth’s series appeared. A year later, the 1752 Murder Act officially legalized the practice as a deterrent to violent crime.

William Hogarth: Fourth Stage of Cruelty (Reward of Cruelty), 1750–51. Red chalk. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1909. III, 32e.

Morganmobile: Justice

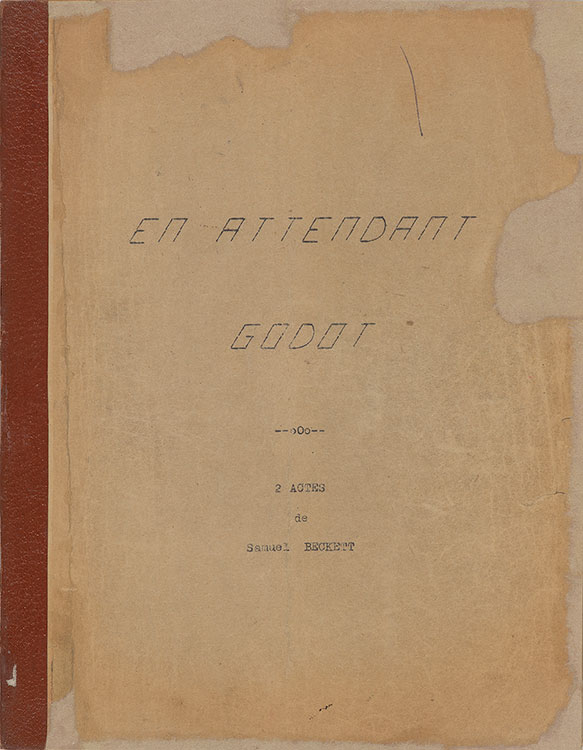

Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” began to be staged in prisons within a year of its debut. Incarcerated performers, and audiences, saw Vladimir and Estragon’s condition as their own: suspended in limbo, subject to caprice and cruelty, forever anticipating an endlessly deferred judgment. “It caused [a] stirring,” recalled Rick Cluchey, an inmate of California’s San Quentin State Prison in 1957, who listened to a performance from his cell and later acted in many plays by Beckett. This is the set designer Sergio Gerstein’s copy of the script for the original production of the play.

Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), En attendant Godot: carbon copy of typescript, Paris, 1952–1953. Purchased on the Drue Heinz Fund, 2001. MA 5071.1

© Samuel Beckett

Morganmobile: Justice

In May 1968, mass protests and nationwide strikes sparked a cultural and social revolution in France. Though his subjects included scenes of physical conflict, Bruno Barbey has recalled that those “out on the streets…had the urge to discuss, to reform the world, to search for freedom.” A stipulation written on the verso of this early press print—“Not to be published without concealing the faces of the protesters”—sought to prevent the image from becoming a tool of state prosecution.

Bruno Barbey (b. 1941), May 6, Paris, 1968. Gelatin silver print with additions by hand. Purchased as the gift of Elaine Goldman. 2016.159.

© Bruno Barbey/Magnum Photos

Morganmobile: Justice

This image in a thirteenth-century psalter (book of psalms), made for an English couple, shows Moses and the Israelites fleeing from slavery in Egypt. As instructed by God, Moses raises his staff, parting the Red Sea so the Israelites can cross. Divine justice is served as Pharaoh’s soldiers—depicted in medieval chainmail—drown in the closing waters. Recorded in Exodus, this story of deliverance from oppression has given hope to countless people up to the present.

Huntingfeld Psalter, in Latin, English and French, England, Oxford, 1212–20. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902. MS M.43, fol. 13r.

Morganmobile: Justice

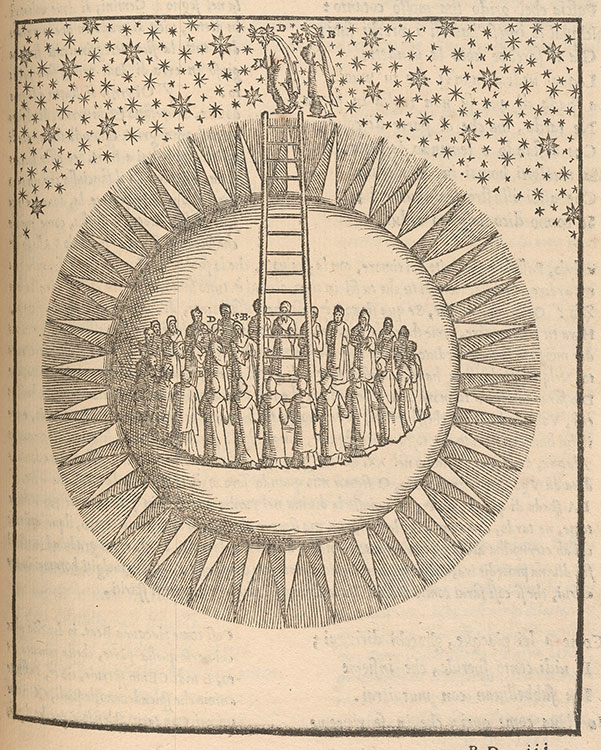

Canto 22 of Dante’s Paradiso begins in the heaven of Saturn, a god associated with the Golden Age and a return to the rule of Justice. The illustrator of this early edition employed a technique known as continuous narrative: the pilgrim is represented twice in one image. He appears near Saint Benedict, surrounded by the contemplatives at the base of a golden ladder, and stands alone with Beatrice following his ascent to the sphere of the fixed stars. From atop the ladder, the pilgrim turns his gaze downward. Seeing through his past self and the layers of heavenly spheres, he beholds for the first time the humble earth—“the little threshing floor,” as he calls it, “that so incites our savagery.”

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), La comedia di Dante Aligieri, con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellutello (Venice: Francesco Marcolini, 1544). Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909. PML 16104.