Morganmobile: Art Within Art

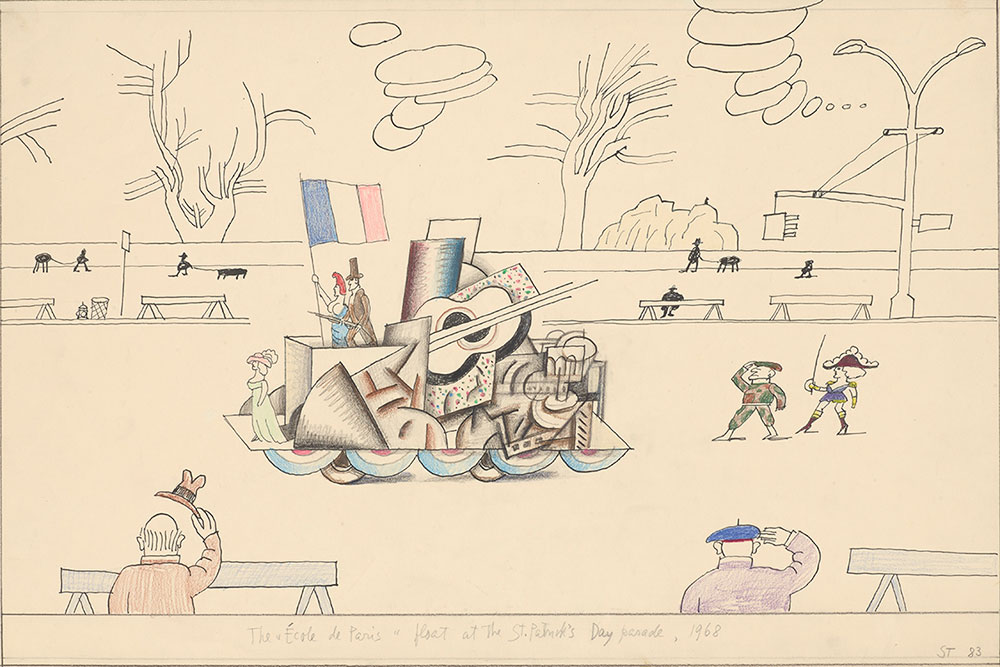

A cubist painting explodes into three dimensions in Saul Steinberg’s New Yorker drawing of an imagined School of Paris float in the 1968 St. Patrick’s Day Parade in New York City.

Saul Steinberg (1914–1999), The 'École de Paris' Float, 1983, graphite, marker, crayon, and colored pencil on paper, 14 1/2 x 23 inches (36.8 x 58.4 cm). Gift of the Saul Steinberg Foundation, 2014.71.

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Morganmobile: Art Within Art

One of the greatest caricaturists of the seventeenth century, Pier Francesco Mola often included recognizable images of himself and his close friends in his drawings. These men peering at the painting of a cosmographer or astronomer have not been identified, but the image is a timeless satire on the art of connoisseurship.

Pier Francesco Mola (1612–1666), The Connoisseurs, pen and brown ink. Gift of Janos Scholz, 1985.90.

Morganmobile: Art Within Art

France’s first generation of paper-negative photographers included a few painters, who pioneered the medium’s use as a graphic art, akin to sketching and printmaking. Charles Nègre also used his camera to document works he submitted to salons of painting. Here, his imposingly framed subject is Le quartier des Moulins (Musée d’ Art et d' Histoire de Provence, Grasse), a variation on his more famous 1852 photograph of the same view (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

Charles Nègre, Oil Presses at Grasse, ca. 1855, albumen print from glass negative. Purchased as the gift of Christopher Scholz. 2016.21.

Morganmobile: Art Within Art

In this image illustrating Psalm 137, the painter Jean Colombe portrayed God’s “holy temple” as a Gothic cathedral, complete with statues of prophets or kings at its portal. Jean may have been inspired by his brother Michel, a sculptor.

Hours of Anne of France, France, Bourges, 1470s, MS M.677, fol. 252v. Purchased by J. P. Morgan (1867–1943), 1923.

Morganmobile: Art Within Art

In a seal carved nearly five millennia ago, horned animals bounding across a field are reduced to arcs and curves—a pattern as immediate and vital as a paper cutout by Henri Matisse. Approximately 2500 years after the seal was carved, a delicate cuneiform inscription was added in the available open spaces within the design. The meaning of the inscription, made at nearly the end of 3000 years of cuneiform writing, remains elusive.

Cylinder Seal with Modern Impression: Pattern of Two Running Goats One Above the Other. Mesopotamia, Early Dynastic I period (ca. 2900–2750 B.C.). Serpentine. Inscription added ca. 400 B.C. Seal no. 48. Acquired by Pierpont Morgan before 1908.

Morganmobile: Art Within Art

“The fool's tongue is, like the rattlesnake's alarum, the providential sign by which we may avoid him.” In his adaptation of the fable about a conceited young mole, Charles H. Bennett applies Aesop's moral to the art critics of his time. Ignorant of its own inexperience and sensory limits, the colorblind creature emerges from underground to mock a painting for its purple grass and non-blue sky. Bennett, who colored his works by hand, left the framed artworks in a mole’s monochrome palette. Aesop remains the prolific author-illustrator’s most widely reprinted work.

Charles H. Bennett (1829–1867), The Fables of Aesop and Others, Translated into Human Nature (London: W. Kent & Co., [1857]). Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987. PML 142654.

Morganmobile: Art Within Art

Giovanni Battista Piranesi cataloged his prints in this trompe l’oeil image of sheets of paper tacked to a masonry wall. The central compartment in the etching lists his major publications, while various kinds of artwork he had for sale appear in an ornamental border. During the course of his career Piranesi periodically reworked the plate to include his most recent creations, and when he ran out of space, he added a second plate. This, one of the latest states of the two-plate print, stands as an unusually comprehensive work of artistic autobibliography.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778). Catalogo delle opere date finora alla lvce da Gio-Battista Piranesi. Rome: Francesco Piranesi, 1780(?). Purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2004.

Morganmobile: Art Within Art

Maurice Ravel’s La valse was premiered by the Royal Flemish Opera Ballet in 1926. It had been composed for the Ballets Russes, but Sergei Diaghilev turned it down, calling it a “masterpiece, but not a ballet,” rather “the portrait of a ballet … the painting of a ballet.” He might have found his judgment confirmed in the figural embellishments Ravel added to this piano arrangement of the orchestral work. The composer himself declared the work “a choreographic poem … a sort of apotheosis of the Viennese waltz … the mad whirl of some fantastic and fateful carousel.”

Maurice Ravel (French, 1875–1937), La valse, arranged for piano, autograph manuscript, 1920. Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection, 1983. Robert Owen Lehman, former owner.

Morganmobile: Art Within Art

When the twenty-one-year-old French artist Hubert Robert arrived in Rome in 1754, he was drawn to the Eternal City’s ancient architecture and ruins. This sheet, however, reveals his fascination with a masterpiece still in the making. The image documents a stage in the construction of the Trevi Fountain (1732–62). The sculptural rocks in the basin are surmounted by wooden scaffolding and fencing while a tarp covers the unfinished central figural group.

Hubert Robert, The South Façade of the Palazzo Poli with the Trevi Fountain under Construction, ca. 1860–61, red chalk, 323 x 447 mm. Gift of Mrs. Allerton Cushman in honor of Janos Scholz and the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Library, 1973.51.

Morganmobile: Art Within Art

William Anthony’s parody of the Laocoön dispenses with the sublime physiognomies of the Hellenistic sculpture, which portrays a Trojan priest and his sons being attacked by serpents. Deflating the noble tragedy of the original, Anthony creates enfeebled, anti-heroic figures who appear more angry than anguished at the fate the gods have dealt them.

William Anthony (b. 1934), Laocoön, 2011, watercolor and graphite on paper. Gift of David and Pamela Chenkin, 2011.21.

© William Anthony

Morganmobile: Art Within Art

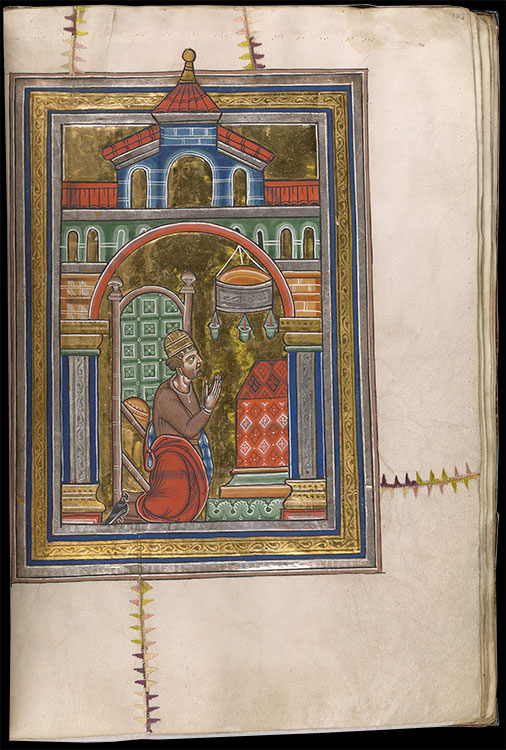

The ornately stitched repairs spanning the margins of this illuminated page were added at some point after the manuscript was completed. On a practical level, they served to reduce distortion of the parchment. But the decorative quality and bright colors of their execution transform the stitches from mere repair into art: at once an aesthetic exercise and an act of devotion.

Dedication of the Church, in “Berthold sacramentary,” Weingarten, Germany, 1215–1217, MS M.710, fol. 127. Purchased by J. P. Morgan (1867–1943), 1926.