Engineering Fantasies

Ultimately, Lequeu’s skills as a draftsman helped him earn a living. He worked in the offices of the national land registry from 1793 until 1815 and at the École polytechnique from 1795 to 1796. His meticulous knowledge of geometry and perspective and his facility in producing exacting wash drawings proved useful in designing maps and representing machinery.

The designs Lequeu made in the first two decades of the nineteenth century are some of his most inventive. He turned his imagination to everything from gardens to temples, from theater interiors to subterranean chambers. Perhaps most striking are the designs in which a building’s form and decoration announce its function, a genre later known as architecture parlante, or speaking architecture. These varied and imaginative designs reveal that Lequeu continued to develop ambitious schemes throughout his bureaucratic career, long after he was forced to retire in 1815 and had abandoned any hope of seeing his creations realized. Anticipating his place in history, he even designed his own tomb.

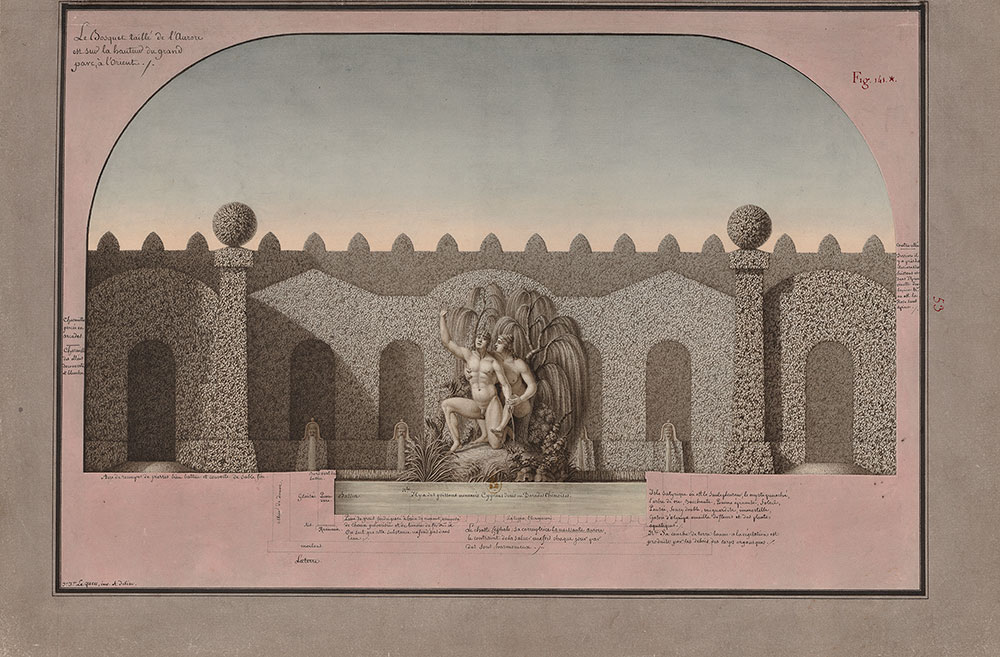

Grove of Aurora, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu here envisaged a “satyr island” with a secluded fish pond surrounded by a topiary enclosure in a “moresque and arabesque” style. The statues at center depict the goddess Aurora restraining the young hunter Cephalus. While in Ovid’s Metamorphoses Cephalus resists the goddess’s embrace and remains faithful to his wife, Lequeu reinvented the tale, recounting that the “chaste Cephalus” was forced by his “corruptress” to “salute [Aurora] each day with harmonious sounds.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Grove of Aurora, from Civil Architecture

Pen and gray-brown ink and wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

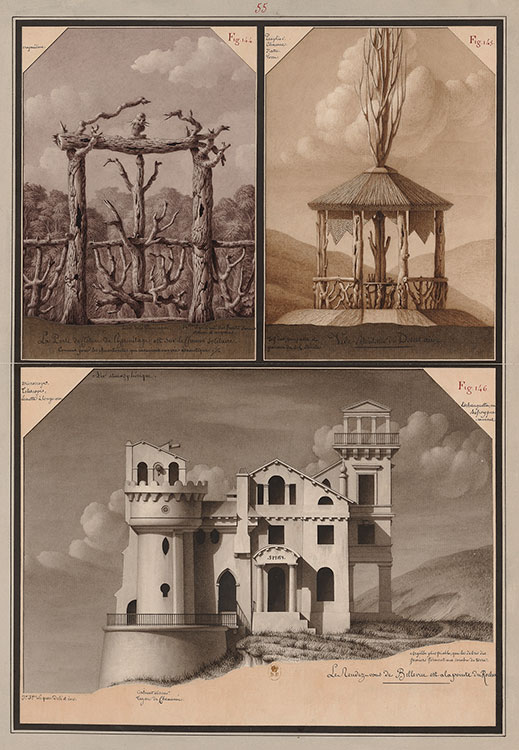

Hermitage Gate, a Desert Drinking Pavilion, and a Hunting Retreat, from Civil Architecture

These three studies explore the architecture of isolation. At upper left, a gate to an anchorite hermitage is composed of a tangle of dead branches, forming an effective barrier to the outside world; at upper right, a vide-bouteille—a pavilion for drinking and outdoor gatherings—is set in a remote location at high altitude. At bottom, a belvedere, or building designed for gazing at a beautiful view, sits at the edge of a cliff. Asymmetrical yet perfectly balanced, the belvedere combines elements of a classical temple, a medieval fortress, and a Renaissance villa. Once inside, a visitor could admire the view through a telescope or one of the curiously shaped windows.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Hermitage Gate, a Desert Drinking Pavilion, and a Hunting Retreat, from Civil Architecture

Pen and black ink, gray and brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Temple of Ceres, from Civil Architecture

This design for a pastoral temple devoted to Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture and the harvest, idealizes rural life. The structure, a curious combination of stone and foliage, is approached through fields of wheat, emphasizing the carved motto “True happiness is found in the countryside.” Inscriptions on the plaques in the canopy of the temple follow the republican calendar. Below, Lequeu transcribed several quotations, including “Work is often the father of pleasure,” from Voltaire’s Upon Moderation in All Things, Study, Ambition, and Pleasure (1738).

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Temple of Ceres, from Civil Architecture, 1793–1805

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

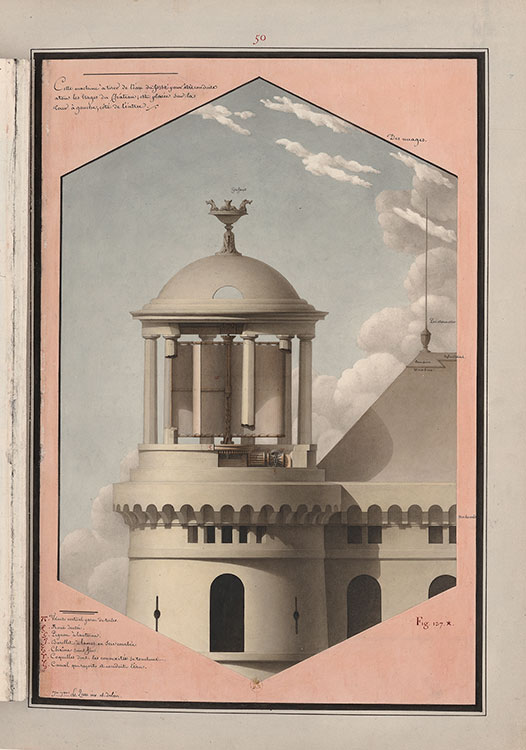

Machine for Circulating Water throughout the Castle, from Civil Architecture

Ever pragmatic, Lequeu included designs for a comprehensive sewage system and a mechanism to distribute water in his depiction of a Moorish pleasure palace. Inside the tower, the wind would lash a stretched canvas, moving a vertical chain that carries a bucket of water from the moat to a channel, which would distribute the water through the structure. At

right, Lequeu added a recently invented lightning rod to protect the building.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Machine for Circulating Water throughout the Castle, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1800–1805

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

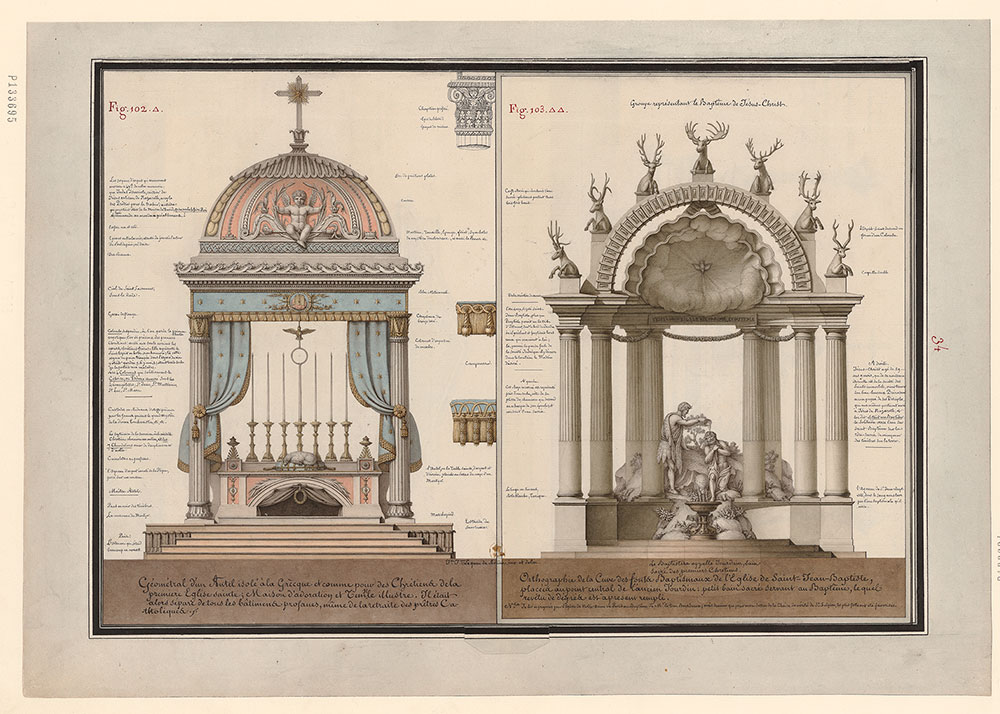

Designs for an Altar and Baptismal Font, from Civil Architecture

Even toward the end of his life, Lequeu continued

to pursue opportunities to show his drawings. In 1821, he submitted these two designs to a competition preceding the baptism of the duc de Bordeaux, grandson of the future King Charles X, planned for May at Notre-Dame de Paris. In the freestanding altar at left, the lamb is a symbol of life, while in the font the same animal symbolizes death through sacrifice.

Lequeu’s design also connects the water of eternal life and the bloodshed of the “artisan from Nazareth.” The altar’s tympanum is ornamented discreetly with the instruments of the Passion, while the apse above the font is crowned with stags’ heads, evoking Psalm 42: “As the deer pants for streams of water, so my soul pants for you, O God."

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Designs for an Altar and Baptismal Font, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1821

Pen and brown and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Chinese-style Gardener’s House and a Terrace on the Banks of a River, from Architecture civile

In the upper design, Lequeu began with the outline of a Cantonese house that he derived from the Scotsman Sir William Chambers’s 1757 treatise on Chinese architecture. He then enriched the facade with ornament of his own invention, including pseudo- Chinese inscriptions, bells, and animal-headed scrolls atop the cornices. The open-air pavilion on the second story is devoted to the rising sun and features a gabled roof decorated—somewhat unexpectedly—with turbaned heads. The lower design on the sheet features a two-story terrace along a riverbank that forms a spectacular gallery of waterspouts, which is flanked by two donjons crowned with tents.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Chinese-Style Gardener’s House and a Terrace on the Banks of a River, from Civil Architecture

Pen and brown and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Indian Pagoda of Intelligence, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu combined disparate traditions in this design of a pagoda crowned with a minaret. The exterior was to be coated in a mixture of lime, sugar, and milk and then polished to create a glittering effect. While the design reflects Lequeu’s idea of Indian Mughal architecture and reveals his curiosity about other cultures, the language used to describe the building is indebted to classical theory.

At the top of the sheet, the artist included three tomb designs. The tomb at right bears a mysterious epitaph: “There she rests among two rival

lovers, separated.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Indian Pagoda of Intelligence, from

Civil Architecture, ca. 1815–20

Pen and black ink, brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

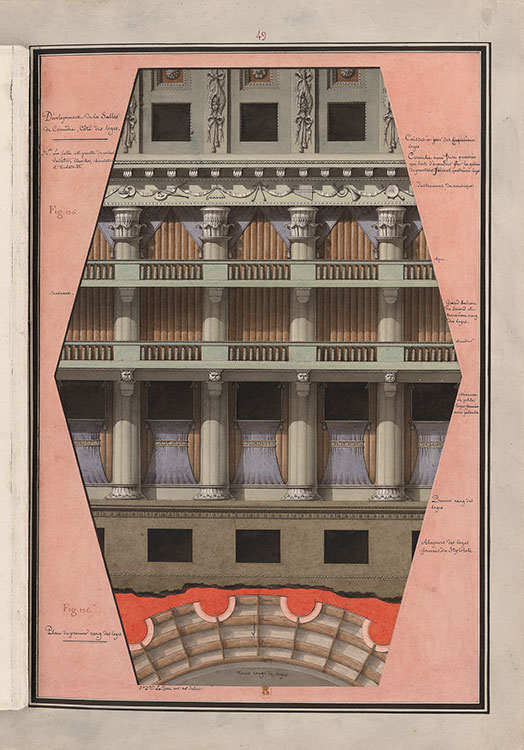

Design for a Theater Interior, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu had an enduring enthusiasm for theater. He wrote at least nine plays (now lost) with such satirical titles as The Man with Two Wives, Nadir the Great, and The False Dmitry, Tsar of Russia. He also produced a number of designs for theaters and stage sets. This design for an auditorium shows five tiers of loges, box seats, and galleries. The restricted depth of the galleries to only three rows of seats, as indicated by the plan at bottom, produces a contrast with the soaring verticality of the entire structure.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for a Theater Interior, from

Civil Architecture

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

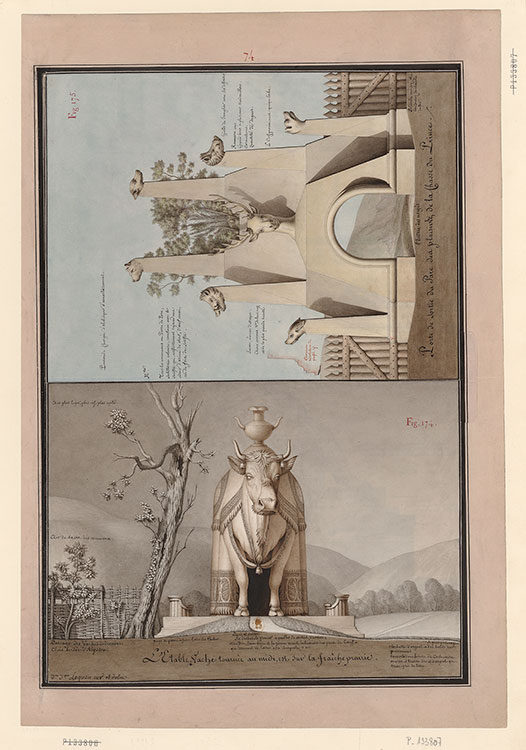

Cow Barn and Gate to the Hunting Grounds, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu tested the limits of architectural symbolism in these two designs where form follows function. The barn below is in the shape of a cow draped in a gold- and silver-studded Indian blanket. Its monumentalism and exotic connotations evoke the colossal plaster-and- wood elephant erected in the Place de la Bastille in Paris in 1813. The upper design depicts an entrance to a princely hunting reserve decorated with the heads of wild boar, deer, and hounds. It was intended to be sculpted in “pork stone,” a mix of limestone and sulfur that, according to the artist, diffused “an odor of cat urine . . . [or] rotten egg.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Cow Barn and Gate to the Hunting Grounds, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1815

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: The term architecture parlante or speaking architecture, was coined in 1852 by the romantic architect Louis Boullée, to describe the works of one of Lequeu's neoclassical contemporaries, Claude Nicolas Ledoux. Speaking architecture is architecture whose form announces its function as this cow-shaped building reveals its role as a barn for cows, or as a roadside vegetable stand in the shape of a tomato, tells you what it's there for. The term was meant to be pejorative and reflects a later perspective on designs produced in the late 18th and early 19th century. While this design for a barn is highly inventive, it's also part of a larger effort by Lequeu's contemporaries to envision eccentrically shaped structures in the form of animals. This isn't as bizarre as it seems. In 1811, Napoleon envisioned a bronze elephant surrounded by a fountain and surmounted by a viewing platform at the center of the newly created, Place de la Bastille. The project advanced as far as having a full-scale plaster model installed in 1813. The bronze was never produced, but the plaster elephant stood for decades deteriorating in the weather. Lequeu's design participates in this wider effort to test the limits of unconventional structures.

Dairy and Chicken Coop, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu’s design for a dairy barn is filled with bovine references: the columns sprout udders and are topped with cow’s heads, and a butter churn sits atop the spire. The exterior announces the building’s purpose in a direct and amusing way. More understated in comparison, the chicken coop is surmounted by a metal dome, meant to reflect sunlight, whose rounded curve resembles an egg—with the figure of a chicken at

its summit.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Dairy and Chicken Coop, from Civil Architecture

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Geometric Map

In 1802, Lequeu was reassigned to an office responsible for cartography in the department of the interior, where he would spend years shifting between positions as a geographical draftsman. Among his responsibilities were new maps of Paris, which were necessitated by Napoleon’s reorganization of the city. In this drawing, produced around the same time, Lequeu indulged in the opposite of documenting the urban fabric: he created a bird’s-eye view of an imaginary landscape with a sinuous river and undulating topography. The artist curiously “signed” the drawing with the playing card at lower left, which contains a pun on the sound of his name: The Heart, or Le Cœur.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Geometric Map, 1801

Pen and black ink, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

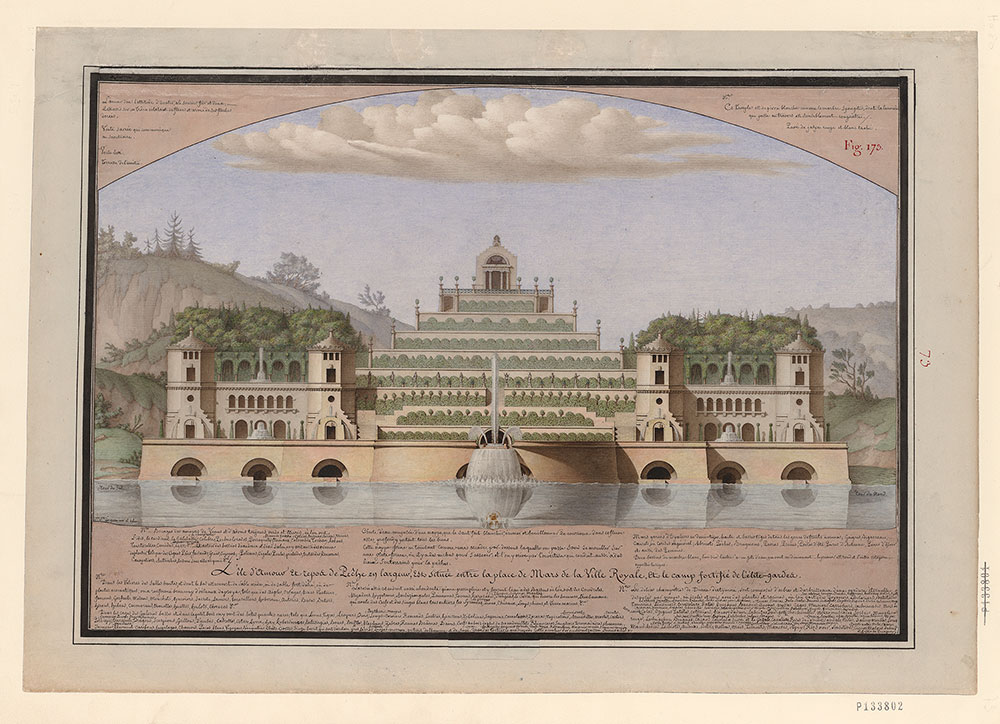

Island of Love and Fisherman’s Rest, from Civil Architecture

Situated between the military grounds of a royal city and a fortified encampment for elite troops, this island offers a quiet place for repose. Rising from the waters, a series of monumental terraces houses a menagerie of wild animals and birds in cages or in the surrounding woods. Lequeu painstakingly enumerated the many creatures in a series of lists. The island is surmounted by a temple of white stone paved in red jasper, which, as Lequeu notes, emits a rosy glow in daylight—an effect the artist had read about in an early eighteenth-century description of a castle in Ankara, Turkey.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Island of Love and Fisherman’s Rest, from Civil Architecture, 1810–25

Pen and black ink, brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: While some of Lequeu's designs were practical or produced for competitions, others describe entire realms he invented. To better understand these imagined environments, we need to delve into the lengthy, handwritten paragraphs that offer even greater detail than the drawings themselves. The notes on this page reveal the incredible depth of Lequeu's book knowledge, his curiosity about the natural world, and his ability to create an environment enriched with unheard-of biodiversity. For example, among the animals found on the island's menagerie, he lists lions, tigers, leopards, bears, lynx, fox, otters, hedgehogs, tamarins, sable, tapirs, sloths, armadillos, beavers, and even unicorns. Many of the more obscure creatures on the list are animals described in travel literature. Thus, the list includes a creature from the Maldives described as a pimones, which is now thought to be a type of shark. Also on the list is a water hog from Zaire called an embiziangulo, which Lequeu found described in a 1714 publication on African Rivers. Lequeu's lists reveal the research that went into developing a vision for his fantasy island.

Temple of Divination, from Civil Architecture

An example of Lequeu’s fascination with ritual spaces, this sheet depicts a temple that would have served as the locus for the initiation of ancient Greek priests. A flaming river feeds into the temple, producing the billowing smoke at center, while Y-shaped divining rods, alluding to the mysteries known only to adepts, adorn the pillars flanking the entrance. To counter the sulfurous odor of the river, the sanctuary would emit an aromatic perfume—the recipe for which Lequeu includes—whose sweet vapor evoked dreams.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Temple of Divination, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1798–1802

Pen and black ink, gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Grotto of the Oceanids, from Civil Architecture

The present sheet invites the viewer into the “marvelous” dwelling of a group of mythological water nymphs. This three-story cavern, illuminated by an oculus, forms a microenvironment replete with water jets, singing birds, and plants growing on compost. A surrounding aqueduct supplies the water for the monumental cascade. Lequeu’s annotations note that the grotto, half-disguised as an artificial mound above ground, was to be situated at the end of a cloister and in front of a labyrinth, an elaborate and entirely imaginary setting.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Grotto of the Oceanids, from Civil Architecture

Pen and black ink, gray and brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

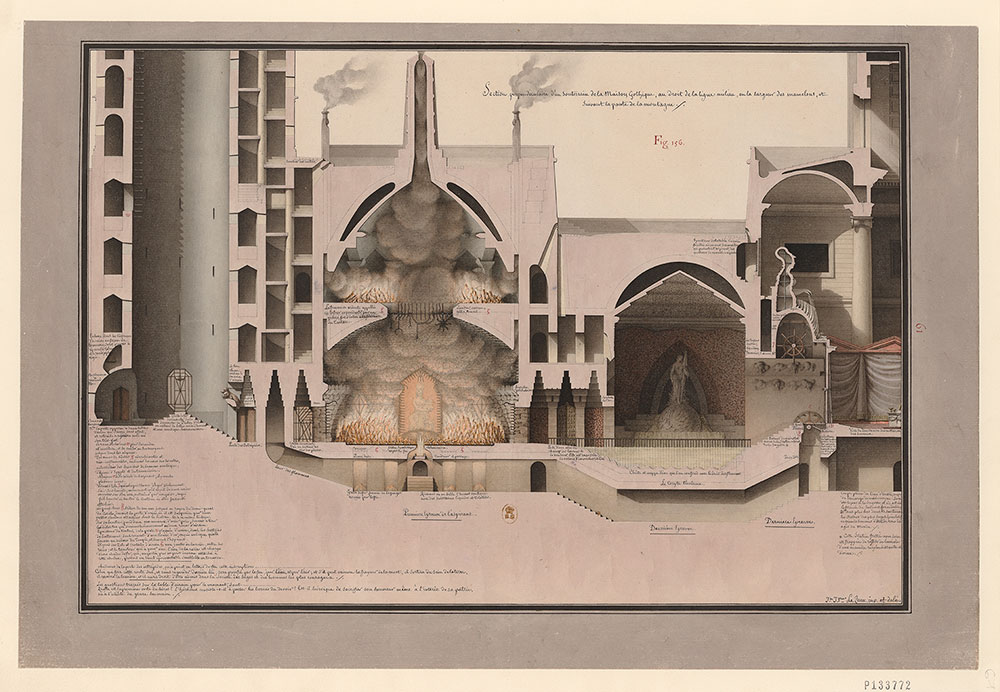

Underground of a Gothic House, from Civil Architecture

Freemasonry was a prominent cultural movement in the France of Lequeu’s day. While he seems to have been part of the brotherhood and knew the secretive Masonic initiation rites, it is not known to which lodge he belonged.

This structure, located behind a temple devoted to Minerva (seated at right), is designed for initiations into the “Society of Sages and Most Courageous Men.” According to Lequeu’s annotations, the ritual to join the brotherhood required initiates to overcome their fear of death through trials by fire, water, and air in subterranean chambers before emerging into the light. Each chamber would be equipped with complex mechanisms meant to produce claps of thunder.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Underground of a Gothic House, from Civil Architecture, 1804–11

Pen and brown and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: The Masonic Brotherhood emerged in France in the 1720s and continued to grow in popularity as the century progressed. The Brotherhood admitted male members from all social classes as well as foreigners, and as a result, the Masons were seen with suspicion by the monarchy and the Catholic Church. Members were associated with lodges or meeting places for local chapters. The democratic nature of the lodges became associated with support for the revolution, and thus membership carried with it a whiff of danger. While we know Lequeu was intrigued by the Masons, recent research has not concluded that he belonged to a particular lodge. Lequeu's preoccupation with Masonic rites informed his work. Ancient Egyptian practices shaped some of the rituals in Masonic lodges and a general fascination with Egypt flourished, after the 1731 publication of the Abbé Terrasson's 6th Volume, Life of Sethos, which purported to be the translation of a lost ancient manuscript, but was actually a fantasy novel. This connection between contemporary ritual and the rites of the ancient world seems to have fascinated Lequeu, who had keenly felt a deep connection to the past. The clandestine rituals of the lodge fueled this design for an underground series of chambers filled with challenges for the initiate.

Cavern in the Gardens of Isis, from Civil Architecture

For this depiction of a grotto in the gardens of Isis, the Egyptian goddess of fertility, Lequeu turned to Ovid’s tale of the nymph Arethusa. She was transformed into a spring to elude being raped by the river god Alephus; the god, in turn, transformed himself into a river to follow her further. Here, Alephus is represented as the cascade at left, and the waters mingle in a cavern whose oculus Lequeu’s inscription refers to as an orifice. The figure of the nymph recalls a description in the erotic Renaissance novel The Dream of Poliphilo. Lequeu owned the 1804 edition of the text.

At upper right, Lequeu envisioned his own tomb, containing his “cadaver embalmed in bitumen.” The sepulchre is surmounted by the instruments of Lequeu’s profession as an architectural draftsman, including a compass, rulers, and porte-crayon. Beneath the flap of paper on which the tomb is drawn, however, is an alternative design bearing a Greek cross—an echo of Lequeu’s bitter remark that he carried the cross his entire life.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Cavern in the Gardens of Isis, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1810–25

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor, patch with revision at upper right

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: The last decade of Lequeu's life leading up to the donation of his drawings to the Royal Library was rife with challenges. At the end of September 1815, the 58-year-old Lequeu was forced into retirement with a modest annual pension. He became increasingly isolated and his morale seems to have deteriorated. His writings reveal his feelings of bitterness and anger toward his peers. He described his outlook in a letter. As for the architect, Lequeu, having lost the property of his ancestors by revolutionary laws and by other misfortunes that result from it, he consoles himself with his wisdom, he cultivates the arts and sciences he loves. Bored with the deceitful world and its extravagances, he seeks in the solitary paths of the fields the secrets of nature, the course of the stars, but above all, he strives to adorn his soul by pure virtue, this gift of God. But he was not to have a tranquil time in his retirement. He struggled, as all urban dwellers do, with noisy neighbors, lamenting to his landlord, "If you have a good memory, you'll recall that my room is my design office where I work. That people at home must not hear a hurly-burly in the morning, including the Lord's days of rest. And even at night, two individuals noisily drop boots and bang shoes." It was in his apartment where he produced over 800 drawings and where he contended with obnoxious neighbors. That Lequeu died at the age of 69 on the 28th of March 1820.